The 1916 Brusilov offensive was intended to bring an early end to World War I—but Russia paid the price for its own failure.

One hundred years ago this summer the Russian empire’s massive Brusilov offensive, which played out along the southern sectors of World War I’s Eastern Front, came close to winning the war for the Allies two years before the 1918 Armistice. The ultimate failure of that effort had sweeping consequences that extended well into the postwar era. It is thus fitting on the anniversary of the campaign that we consider one of the most significant, if lesser known, what-ifs of modern military history.

When the war began in August 1914, Great Britain and France placed a great deal of hope in the ability of the vaunted Russian “steamroller” to absorb some of the combat punch from the expected main German effort in the West. Those hopes died by month’s end following the First Battle of Tannenberg, in which the Germans destroyed the greater part of a Russian army—though it could be argued the ill-starred Russian invasion of East Prussia that led to Tannenberg spared France by drawing off German forces from the Western Front at a critical moment. In Austrian Galicia, however, the Russian armies scored a decisive victory over the heterogeneous elements of the Austro-Hungarian army, forcing it into the Carpathians and hobbling it for the remainder of the war. These events established a pattern that persisted throughout the conflict in the East—the qualitatively superior Germans could generally defeat the Russians, while the Russians held the same advantage over the Austro-Hungarians.

In fact, it was the necessity of shoring up their faltering ally that forced the Germans to launch their Gorlice-Tarnów offensive out of the Carpathians in May 1915. What was initially conceived of as a local attack soon expanded far beyond its planners’ expectations, and by summer’s end the Central Powers had driven the Russians out of Poland and part of the Baltic coast. Russia’s manpower losses were correspondingly massive, its army suffering an estimated 1,410,000 killed and wounded and another 976,000 captured.

Despite this disaster, which further exposed the incompetence of Russia’s command structure and seriously undermined public support of the war effort, by early 1916 Russian forces had largely rebounded from their losses. Furthermore, a shell shortage that had bedeviled the army the previous year was being rectified as the Russian economy gradually adjusted, however imperfectly, to the demands of modern war.

Russia’s newfound confidence coincided with a decision by Allied representatives meeting in Chantilly, France, in December 1915 to coordinate their attacks for the coming summer, in order to prevent the Central Powers from using their superior communications to shift reserves from one front to another. The British and French would attack along the Somme River, the Italians would renew their efforts along the Isonzo River, and the Russians would attack along their front—all within a month of each other. However, the massive German attack at Verdun in late February quickly drew off French reserves and eventually made the Somme offensive a mostly British affair.

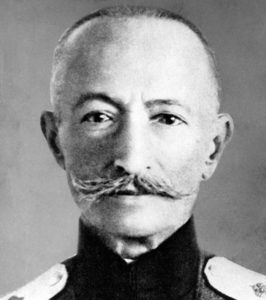

Representatives of the Russian high command met at supreme headquarters, Stavka, in Mogilev on April 14. Czar Nicholas II, who had assumed the role of commander in chief the previous fall, formally presided over the meeting, but General Mikhail Vasilyevich Alekseyev, his chief of staff, actually conducted the proceedings, the emperor essentially rubber-stamping his recommendations. Despite the improvement in the army’s fortunes, both General Aleksey Nikolayevich Kuropatkin, commander of the Northern Front army group, and General Aleksey Yermolayevich Evert, his opposite number on the Western Front, opposed launching offensives in their sectors, citing the Germans’ powerful defenses and their own shortage of heavy artillery. Only General Aleksey Alekseyevich Brusilov, newly appointed commander of the Southwestern Front army group, argued for an attack against the Austro-German forces facing him. Alekseyev, more than a little surprised, agreed to Brusilov’s proposal, although he warned him he could expect no reinforcements. However, Brusilov’s pugnacious attitude seems to have sufficiently embarrassed the others into reluctantly agreeing to launch supporting attacks.

On April 24 Stavka issued a directive assigning Evert’s Western Front army group to make its main effort from the Molodechno area in the general direction of Ashmyany and Vilnius, while the Northern Front would support it with a converging attack from the Illkust–Lake Drisvyaty area in the direction of Novoalexandrovsk, or from the area south of the lake toward Vidzy and Utsyany. The Southwestern Front was to make its main push along the northern wing in the direction of Lutsk.

Brusilov’s plan called for the Eighth Army to make a two-pronged effort toward Lutsk and Kovel’. That attack by his northernmost army would offer the most immediate assistance to the neighboring Western Front and threaten the vital railroad junction of Kovel’, the capture of which would greatly impede the ability of the Central Powers to maneuver men and materiel from north to south. The two center armies (Eleventh and Seventh) would carry out strictly supporting attacks along their front, while the Ninth Army would make a secondary attack along the front’s left wing in order to draw off enemy reserves and perhaps prompt Romania to join the Allies.

The Southwestern Front would attack with 573,000 infantry and 60,000 cavalry, supported by 1,938 guns, of which only 168 were heavy caliber. The Central Powers forces opposing them included the Austro-Hungarian First, Second, Fourth and Seventh armies and the German South Army, which collectively numbered 437,000 infantry and 30,000 cavalry, plus 1,846 guns, of which 545 were heavy. Thus, while the Russians enjoyed a significant manpower advantage and were almost equal in the number of guns, they were notably inferior in the all-important category of heavy artillery. However, the fact that the majority of enemy forces facing them were Austro-Hungarians, hobbled by poor training and ethnic divisions, gave the Russians a reasonable chance of success.

Brusilov decided on a novel method for conducting his attack. Up till then combatants on both the Eastern and Western fronts had organized their attacks around a single sector. Such attacks involved enormous masses of artillery and men, as had been the case at Verdun in February and during the Russians’ unsuccessful offensive around Lake Naroch in March. It was virtually impossible to keep such large-scale preparations hidden from the enemy, who generally had plenty of time to move in reserves to blunt the attack. Thus such assaults usually collapsed in short order with a great loss of life for the attacker and miniscule territorial gains.

Rather than repeat such a costly and ineffective gambit, Brusilov instead decided to launch several simultaneous attacks along the entire 280-mile front. Each army commander was instructed to organize the forces in his sector, while a number of corps commanders were in turn instructed to prepare breakthrough zones in their sectors, for a total of four army and nine corps breakthrough sectors. Brusilov calculated that the widespread preparations would confuse the enemy as to the direction of the main attack.

Russian intelligence had revealed the presence of at least three fortified enemy defensive zones, approximately 1 to 3 miles apart, girded by multiple rows of barbed wire. Each of these zones, in turn, comprised no fewer than three trench lines, each 150 to 300 paces from each other. The enemy had strengthened these defenses with communications trenches, electrified wire and explosive devices.

Russian tactical preparations for overcoming these defenses were unusually thorough. Their intelligence had studied the enemy positions and supplied commanders at all levels with the appropriate maps. The Russians also moved up their trench line at night until by the time of the attack they stood no more than 100 paces from the enemy positions. So as not to give away the time of the attack, troops of the first assault wave moved up to their jumping-off positions only a few days before the start of the offensive.

Once again, however, the Central Powers upset the Allies’ plans by launching an offensive of their own—this time by Austro-Hungarian armies in the Trentino region of northern Italy on May 15. When Italy urgently appealed for assistance, Russia responded by moving up the date of the Southwestern Front’s offensive to June 4. The Western Front’s offensive was to begin on June 10 or 11.

At dawn on June 4 Russian guns launched an opening barrage along the entire front, in places lasting from six to 46 hours. The most impressive advance took place along the main attack axis, where General Aleksey Maksimovich Kaledin’s Eighth Army broke through Austro-Hungarian defenses along a 50-mile front, advanced 15 to 21 miles and captured Lutsk on June 7. According to General Erich von Falkenhayn, then chief of the German General Staff, “The part of the Fourth Austro-Hungarian Army, which was in line here, melted away into miserable remnants.” South of the breakthrough the Russian Eleventh Army under General Vladimir Sakharov made almost no progress and, in fact, was forced to fend off enemy counterattacks. General Dmitry Shcherbachev’s Seventh Army advanced slightly, throwing the enemy behind the Strypa River. On the far southern flank General Platon Lechitsky’s Ninth Army pushed the defenders across the Prut River and captured Chernovtsy on June 18. By June 9 Brusilov claimed to have taken more than 70,000 prisoners and 94 guns, plus large amounts of other military equipment.

The commander’s pleasure at a well-earned success was short-lived, however. On June 14 Alekseyev informed him Evert would be unable to attack on the appointed date, supposedly due to bad weather, although he assured Brusilov the Western Front army group would launch its offensive on June 18. However, Alekseyev also said Evert was reporting that enemy forces opposite his attack sector were too strong. The Western Front commander then appealed to the emperor to shift the attack toward Baranovichi, and the latter agreed, with the proviso the attack be launched no later than July 3.

Brusilov later bitterly recalled that his worse fears had been realized, writing, “I would be abandoned without support from my neighbors, and that in this way my successes would be limited only to a tactical victory and some forward movement, which would have no influence on the fate of the war.” He knew that in the absence of support the enemy would be free to throw all available reserves against him. Brusilov suspected that Alekseyev’s references to the emperor were merely a convenient screen, as Nicholas II was, in his words, “a child” when it came to military affairs. He instead believed the fault lay in Alekseyev’s lack of moral courage in facing up to Evert and Kuropatkin, who had been his superiors during the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War. Had the Russians another supreme commander in chief, he concluded, Evert would have been relieved for insubordination, and Kuropatkin would never have received a responsible command.

The Central Powers were quick to exploit the Russians’ dithering and began to transfer sizable reinforcements, mostly German, to the threatened zones. The transfers brought in units not only from the northern sector of the Eastern Front but also from France. Taking advantage of their superior rail links, they quickly rushed forces east, and as early as mid-June they were attacking the Russian penetration around Lutsk. However, as the German assaults were delivered piecemeal, they achieved little and succeeded only in temporarily halting the Russian advance. A lull then settled over the front, as each side prepared to renew its efforts.

Meanwhile, to the north the Western Front’s long-delayed Baranovichi offensive began on July 3 and almost immediately collapsed in bloody failure, just as Brusilov had predicted. Given the continued inertia along Kuropatkin’s Northern Front, this meant the enemy remained free to shift his available reserves against the Southwestern Front.

Regardless, Brusilov pressed gamely on, though he must have realized the time for achieving any real gains had passed. On July 5 the Eighth Army, supported by General Leonid Lesh’s Third Army, which had been transferred from the Western Front, renewed the assault on Kovel’. By mid-month they had reached the Stokhod River immediately west of the city and had captured several bridgeheads. Lieutenant General Erich Ludendorff, who with General Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg commanded German forces along the northern sector of the Eastern Front, later recalled the action: “This was one of the greatest crises on the Eastern Front. We had little hope that the Austro-Hungarian troops would be able to hold the line of the Stokhod, which was unfortified.” However, the Austro-Hungarians, supported by the Germans, were just able to stem the Russian advance through the swampy terrain along the river. There the exhausted Russians bogged down, then prepared to renew the offensive.

To the south Eleventh Army remained essentially in place, fighting just to hold its gains against fierce counterattacks. Territorial gains were greatest in the south, where the Seventh and Ninth armies again pushed Austro-Hungarian forces back to the Carpathians before also running out of steam.

As Russian troops along the decisive axis continued preparations for a renewed attack, Stavka belatedly started shifting reserves to Brusilov’s front. These reserve forces formed the core of the new Special Army, which with Third Army was directed to capture Kovel’. Eighth Army was directed due west toward Volodymyr-Volyns’kyy, while Eleventh Army was to attack toward Brody and Lwow. The Seventh and Ninth armies were to move west toward Halych and Stanislav.

On July 28 the Russians resumed their offensive along the entire front. Brusilov later recalled, “I continued the fighting along the front, but without the previous intensity, trying to spare people as much as possible and only insofar as it was necessary to tie down as large a number of enemy forces as possible, thus indirectly assisting in this way our Allies—the Italians and French.” To what degree this self-serving statement is true is open to interpretation. What is not is the attack’s lack of success toward Kovel’, where the Russians were held to miniscule gains and heavy losses along the Stokhod. Farther south the Russians captured Brody and Stanislav, but by early August it was clear the offensive had run its course, although sporadic fighting continued into the fall.

Despite its disappointing conclusion, the so-called Brusilov offensive nevertheless achieved impressive results. The general himself later claimed that from June through mid-November his forces had captured more than 450,000 of the enemy and inflicted some 1,500,000 casualties. While these figures are likely exaggerated, it was clear the Austro-Hungarian army had suffered a catastrophic defeat and would henceforth require German support to keep fighting. In exchange for German assistance the Austro-Hungarians were forced to accept an extension of Hindenburg’s authority as far south as Brody. The fate of the dual monarchy was bound to that of Germany to the bitter end.

Brusilov’s offensive did succeed in having an impact on other fronts. In France the Germans were compelled to limit operations around Verdun to forces already at hand, while farther north they had to cancel plans for a pre-emptive attack against British offensive preparations along the Somme. Likewise, the Austro-Hungarians had to call off their Trentino offensive and dispatch forces to Volhynia. Brusilov’s initial success also convinced Romania to throw in its lot with the Allies and declare war on the Central Powers on August 27. By then the crisis had passed, however, and the Germans and Austro-Hungarians were able not only to halt the Romanian offensive in Transylvania but also launch a decisive counteroffensive that crushed the Romanians by year’s end.

In the end the Brusilov offensive had been a near thing and could have achieved much more had the Russian high command been able to organize anything approaching a coordinated offensive along the entire front. The drain on German reserves might have enabled the Russians to destroy the opposing Austro-Hungarian armies and perhaps bring about the collapse of the empire itself. That, in turn, would have opened the Italian and Macedonian fronts to Allied penetration, as was eventually the case in 1918. The resulting strain on the German war effort would certainly have been too much, conceivably leading to an Allied victory in 1917, obviating the need for American involvement in the war. Such an outcome would have not only spared the combatants two more years of bloodshed but also enabled Europe to put its own house in order.

The failure of the offensive to achieve such a decisive strategic result had especially tragic consequences for Russia. Its losses in 1916 totaled more than 2 million dead and wounded and 344,000 captured, with 1.2 million casualties and 212,000 prisoners in the summer campaign alone. On the home front an initial patriotic upswing prompted by the initial successes gave way to bitter disappointment over the high command’s bungling, in turn undermining what little faith the country’s educated elite retained in the czarist system. As for the peasant masses, they had grown increasingly weary of dying for a cause they did not understand. Dissent spread, the desertion rate climbed, and as early as autumn 1916 there were reports of soldiers refusing to attack. All of this presaged the collapse of the imperial army in early 1917 and the country’s descent into revolution, military defeat and civil war.

Richard W. Harrison is a researcher living in Moscow. He has previously worked at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow as an investigator with the Department of Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. For further reading he recommends his The Russian Way of War: Operational Art, 1904–1940, as well as John R. Schindler’s Fall of the Double Eagle.