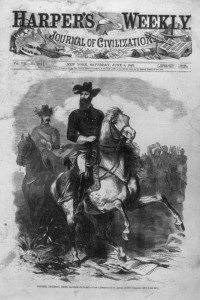

The Union’s eight-month struggle to conquer Vicksburg, Miss., culminated in a 47-day siege that ended on July 4, 1863—one day after the Federal triumph at Gettysburg. Terrence Winschel, former chief historian at Vicksburg National Military Park, has written nine Civil War books, including Triumph and Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign, first published in 1999. We recently spoke with Winschel from his home in Vicksburg about the epic campaign’s leaders, setbacks and losses.

1. Why was Vicksburg so important?

Even George Meade referred to it as “second in splendor if not the first in real consequences.” At Vicksburg, not only did the North gain control of the Mississippi and split the Confederacy in two, but it also eliminated an entire army of 29,500 men. The South lost hundreds of square miles of territory, plus 254 cannons, 50,000 shoulder weapons, 38,000 artillery projectiles, 600,000 rounds of rifle ammunition, etc.—a staggering loss of men and materiel. Gettysburg was far bloodier, but Vicksburg was vastly more significant in its results and consequences.

2. How critical was Grant’s ability to improvise as the campaign progressed?

Grant was a 3-D thinker, a modern warrior by any definition. Throughout the campaign he demonstrated a level of flexibility that no other general, North or South, could boast. That, coupled with his dogged determination and firm resolve, made him the premier American soldier of his day. And his ability to cooperate as he did with Admiral David Dixon Porter’s fleet was a key factor in the Union victory.

3. William Sherman called Benjamin Grierson’s April 1863 raid on the Southern Railroad of Mississippi the “most brilliant expedition of the Civil War.” Do you agree?

Most important was the impact the raid had on Confederate commander John C. Pemberton, who became obsessed with Grierson’s Raiders after they tore up the tracks and destroyed culverts and water towers at Newton Station, putting one lifeline to the Vicksburg garrison out of commission for a period. They went on to wreck the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad’s tracks at Hazelhurst and between Brookhaven and Summit, Miss. As Pemberton turned his attention to the raiders, Grant was marching through Louisiana looking for a suitable crossing below Vicksburg. Pemberton stripped his river defenses of cavalry to pursue the raiders, and dispersed available infantry to guard any attempt by Grant to cross the Mississippi. Pemberton did have numerical superiority on Grant early in the campaign, but now he was not able to concentrate his manpower in time. That gave Grant a numerical edge in every engagement leading up to the siege.

4. Pemberton, a Pennsylvanian by birth, correctly predicted “Obloquy…I know will be heaped upon me” for losing Vicksburg. How much of the blame is deserved?

Like many of his contemporaries, Pemberton was elevated in rank and responsibility beyond his capacities. He was of course up against a modern warrior in Grant. Few, if any, of his contemporaries could have done better at Vicksburg. Yes, he should shoulder some of the blame, but others must be blamed, too: Jefferson Davis meddled in the campaign from a distance; Joe Johnston abandoned Pemberton altogether; William Loring kept working against his commander. But Pemberton faced superb Union leadership and fighting, from Lincoln down through the men in the ranks.

5. How about socialite Emma Balfour’s famous Christmas Ball?

In the fall of 1862, Grant divided his force at Memphis into two wings and advanced south on Vicksburg, with Pemberton’s forces falling back from the Coldwater River before digging in at Grenada. Facing a strong enemy force and a flooded river, Grant ordered the wing under Sherman back to Memphis, hoping Sherman could move rapidly by water to capture Vicksburg while his own wing kept Pemberton occupied in northern Mississippi. On December 22, Confederate Generals Earl Van Dorn and Nathan Bedford Forrest led raids on Grant’s supply bases at Holly Springs and the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Sherman was en route from Memphis to Helena, Ark., when he heard reports of the disaster at Holly Springs, reports confirmed when he reached Helena. But Sherman was undaunted, confident he could reach Vicksburg by water faster than the Confederates could by rail. He would lose that race. When word reached Vicksburg that Grant was apparently falling back, jubilation swept the city, prompting Dr. William Balfour and his wife to host a Christmas Eve ball where Confederate officers danced with Vicksburg belles—unaware of Sherman’s approach. Sherman might have succeeded had a young black girl not spotted his flotilla near Lake Providence, La., and informed nearby telegraph operators who got word to Vicksburg garrison commander Maj. Gen. Martin Luther Smith. He evacuated the city’s women and children, then prepared to meet Sherman, who finally landed on December 26. For the first few days, fighting escalated. On the 29th Sherman launched an attack, saying, “…we’ll lose 5,000 men before we take Vicksburg, and may as well lose them here as anywhere else.” He suffered a bloody repulse, losing 1,776 men to the Confederates’ 187.

Terry Winschel’s books can be purchased at Vicksburg National Military Park, 3201 Clay St., Vicksburg, MS 39180. Call 601-636-0583 or visit nps.gov/vick/learn/bookstore.htm