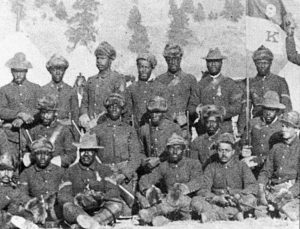

The shadows were lengthening on a crisp afternoon on December 26, 1867, as the soldiers at Fort Lancaster, Texas, went about their duties and looked forward to the bugler sounding ‘Retreat,’ to end the winter day’s labors, followed soon enough by ‘Mess Call’ and the evening meal. Neither Captain William Frohock nor the 58 black troopers of Company K, 9th Cavalry, had any premonition of the crisis that was about to strike the isolated post as 4 o’clock neared. Part of a young regiment whose reputation was already marred by mutiny and the murder of an officer by his men, Company K was fated to confront overwhelming odds in a struggle for its survival. Dealing with this Texas-size challenge would ultimately help to restore the regiment’s tarnished image and establish a continuing tradition of gallant service for the senior unit of black horse soldiers in the Regular Army.

Fort Lancaster had been established on the banks of Live Oak Creek in 1855 by a detachment from the 1st Infantry Regiment. The nearby watercourse flowed by the western limits of the new post barely two miles above its junction to the south with the brackish, sinuous current of the Pecos River. Hard against the parade ground to the north and east rose the lowering heights of the bluffs and ridgelines that marked the ancient valley of the Pecos, whose name was derived from the Spanish puerco (‘bitter’). The bluecoated, mule-mounted infantrymen had provided both a haven for travelers and escort parties for travelers along the bleak and Indian-haunted road linking San Antonio and El Paso until Texas left the Union early in 1861. The garrison marched eastward to surrender to the Confederate authorities, and the U.S. Regulars were quickly replaced by detachments of the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles, who kept watch on the region until the spring of 1862, when Fort Lancaster was abandoned to Indian vandalism and the ravages of the elements. Its sturdy stone and adobe structures were soon reduced to hollow shells, as coyotes stalked the brush-strewn parade ground.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1867, the 9th Cavalry reoccupied the abandoned prewar posts at Fort Clark and Camp Hudson to the south of Lancaster, and Forts Stockton and Davis to the immediate west of the station on the Pecos. Fort Lancaster became a sub-post of Fort Stockton, which was some 75 miles to the east. Company-size forces were posted to temporary duty for several months at a time, quartered amid the crudely refurbished ruins of the old barracks and sharing the post with a relay station of the San Antonio-El Paso stage line.

Much hard work lay in store for all of the 9th’s companies that summer and fall as they molded adobe bricks, hewed limestone and cut wood to rebuild the derelict posts. There were at least two brief skirmishes fought with the Apaches while escorting stages west of San Antonio, and three troopers lost their lives. But there had been no other chance for the unit to prove itself in action and expunge the blot on its reputation that dated to March of that year, when a mutiny had erupted amid the five companies that were encamped at San Pedro Springs, on the outskirts of San Antonio. A drunken company commander, Lieutenant Edward M. Heyl, had opened fire with a revolver upon his own troops of E Company after a long period of abusive behavior toward them. Heyl, a man of limited education, deep prejudices and an abiding taste for liquor, christened his black horse ‘N——’ and treated his soldiers with open contempt and physical abuse. Resentment flared into a mutiny that left Lieutenant Seth Griffin and 1st Sgt. Harrison Bradford dead before it was quelled. The abusive Heyl escaped with a reprimand, while several enlisted men were court-martialed and imprisoned. Lieutenant Frederick W. Smith, who had killed trooper Bradford while suppressing the mutiny, was now assigned to Captain Frohock’s Company K as the disgraced regiment strove to redeem itself in the eyes of the Army and the public alike.

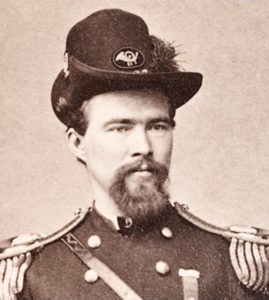

Company K may have been a gloomy portion of a troubled regiment as 1867 neared its end amid that mesquite and cat’s-claw-dappled expanse of western Texas, but its commander was no stranger to either deadly conflict or service with black troops. The Maine-born Frohock had been commissioned into the 45th Illinois Volunteer Infantry late in 1861, seeing service under Ulysses S. Grant at Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, Shiloh and the siege of Vicksburg. He suffered both wounds and bouts of illness during those first two years of the war. In January 1864, the veteran captain had been promoted to colonel and given command of the newly organized 66th U.S. Colored Troops (Infantry), leading the ex-slaves in garrison duty at Goodrich Landing and Lake Providence, La., in addition to eight combat actions fought between March and August of that year. The continuing effects of wounds and illness compelled Frohock to resign the following September, but he left the Army with a brevet promotion to brigadier general for ‘gallant and meritorious service.’

With his wounds healed and his health restored by the spring of 1866, he sought and received a Regular Army commission, first as a lieutenant in the 15th Infantry and then as a captain of the new 9th Cavalry. Unlike many postwar officers, Frohock apparently held no reservations about serving in one of the six black regiments that had been added to the Regulars’ establishment that July. Some officers shunned service with the ‘brunettes’ because of blatant racial prejudice. He must have been aware of the potential for resentment in the ranks against his lone subaltern in the company, Lieutenant Smith, for his shooting of the trooper during the March mutiny. Whatever hard feelings may have existed, Smith was apparently astute enough at leadership not to exacerbate the situation. A veteran of enlisted service in two Massachusetts regiments, he had won a lieutenancy in the 1st U.S. Cavalry in late 1863 before taking a postwar transfer to the 9th. A combat veteran with a brevet captaincy for valor, Smith knew the vagaries of men and war. He was to prove an asset to his commander in the challenging hours ahead that afternoon in December 1867.

Nothing marked the day after Christmas as unusual. A mounted guard detail was driving the company’s horses and mules northwestward from the grazing grounds east of the post through the garrison to reach the watering place on the shady, brush-lined banks of Live Oak Creek. A wagon was already down at the creek, where civilian teamster William Sharpe and three soldiers were filling casks and barrels with water for cooking and washing. None of the soldiers suspected that they were in danger, and despite the high ground that loomed next to Fort Lancaster, Captain Frohock had curiously neglected to establish an observation post that could monitor the approaches to the fort from the north, west and south. That oversight had allowed two large groups of Kickapoo raiders to move undetected down the Live Oak Creek corridor from the north. Kickapoos had been most unfriendly to Texans since January 8, 1865, when Texas state troops and militia had attacked them on Dove Creek. After routing the Texans in that fight, the Kickapoos had resettled in Mexico and begun an incessant campaign of raids into Texas. The lead group on the December 1867 raid had already moved downstream to the south before the water detail had reached the creek, and those Kickapoos were now poised to strike at the post from that direction, while the second contingent of braves closed on the unsuspecting Sharpe and his companions even as the horse herd neared the watercourse and the oncoming raiders.

Teamster Sharpe saw the braves as they approached from upstream, using the creek-side vegetation to screen their approach toward the post and the oncoming horse herd. He shouted an alarm to his companions before he was lassoed and dragged away to be killed. The soldiers prudently melted into the brush and remained hidden for the next several hours as the nearby landscape was flooded with hostiles. The Kickapoos quirted their ponies upslope from the creek bed, charging the horse herd and its startled guards. A firefight erupted as the handful of herdsmen used their pistols and carbines to hold the raiders at bay long enough to turn the animals around and send them thundering back toward the post and the sanctuary of the stone-walled corral. During the pursuit two of the troopers — Andrew Trimble and Ed Boyer — were lassoed and pulled from their saddles. Like Sharpe, they were dragged off and butchered in the brush. The surviving members of the guard detail managed to keep the animals moving toward the fort despite the best efforts of the Indians.

The sound of gunfire alerted the garrison, and the troops seized their weapons as Frohock, Smith and a first sergeant named Underwood strove to organize a hasty defense of the post and deliver fire in support of the oncoming herdsmen and their fleeing animals. The black troopers were still rushing to establish a skirmish line when a portion of the northern contingent of attackers swung wide around the herd and charged directly through the center of the post as the second party of warriors came up from downstream and began threatening the soldiers from the west and south.

Amid the noise and confusion, the handful of mounted troopers chivied the herd toward the corral, only to find the bars still up at its entrance. The frightened animals milled about in panic. ‘Such, I regret to say, was the panic among them [horses] and so close upon us were the savages,’ Frohock later reported, ‘that it was found impossible to control them long enough to open the corral.’ Company K was by now deployed in a crescent-shaped skirmish line disposed to cover the northern, western and southern approaches to the fort. The men maintained a steady fire with their Spencer repeating carbines and .44 Remington revolvers. The balance of the northern group of attackers pressed their advance as far as the stage station on the northern edge of the post, but the soldiers stood firm, and the Kickapoos fell back before the lash of the Spencers’ rolling volleys of .50-caliber rimfire rounds.

More than 400 Indians were by now arrayed against the lone company of yellowlegs, but the men continued to work the levers of their carbines with grim efficiency. As Company K held the line against the warriors, the horse herd became completely uncontrollable and bolted southward, much to Captain Frohock’s dismay. In retrospect he realized that the herd’s escape marked a decisive point in the action. ‘Had this stampede not occurred, it is doubtful if the defense against such overwhelming odds could have been successful,’ Frohock wrote, ‘but upon the emergence of the horses the savages halted and formed in lines of battle, extending over a mile, to cover them.’

Loath to lose his mounts without staging a final effort to recapture them, Frohock left a bare squad of troops to defend the post and then advanced southward with most of the company in a bid to take back the horses. The dismounted troopers, he reported, ‘deployed as skirmishers [and] advanced upon their lines, which, receiving our fire, broke, and reformed to the rear several times, always, however, keeping the horses behind them and themselves beyond the reach of our shots.’ The Kickapoos realized that the Spencers’ firepower was lethal out to about 200 yards, but also that the looping, rainbowlike trajectory of its heavy slug propelled by a rather modest 48-grain powder charge in the thin-walled rimfire cartridges made the Spencer an arm of limited accuracy and effectiveness at longer ranges. The tribesmen thus prudently kept at a distance as they rounded up the windblown horses and brought the herd firmly under their control while trading long-range shots with the soldiers.

The fight sputtered on for a time, and then trouble erupted again from the north as another attack took form against the thinly defended fort itself. Captain Frohock’s wife and sister-in-law had elected to share the Spartan attractions of life at Fort Lancaster with him, and now they stood at risk as the Kickapoos mounted another charge on the sprawling collection of ruins. The officer heard the fresh outburst of firing. ‘Perceiving the impossibility of recovering the horses I recalled the principal part of the company from the pursuit and hastened to repel the attack, which was successfully accomplished after sharp firing,’ he said. Sergeant Underwood remained behind with a squad to confront the southern war party while Frohock double-timed back to the post with the rest of the company, arriving to join the stay-behind squad in a desperate defense staged from amid the cover of the ruined barracks and outbuildings at the northern end of the parade ground. Muzzle flashes stabbed spitefully out from the frameless doorways and windows. At the same time, arrows whizzed back from the brush, and Kickapoo muskets sent bullets whining off the limestone or cratering the adobe brickwork. During fierce interval of combat Mrs. Frohock and her sister filled their aprons with cartridges and calmly distributed more ammunition to the defenders.

For a time, while Captain Frohock was away from the fort, his command had run the risk of annihilation. He had no way of knowing that a much larger force of Kickapoos, perhaps as many as 900 braves, had been approaching the scene of the fight from the north along Live Oak Creek even as he sought to recapture his animals. At one point, as he hurried to return to the post, his little command had been split into three different portions, none of whom was within immediate supporting distance of the other two. A coordinated attack by all the groups of Indians on the field at that juncture might have overrun and destroyed the entire company even in the face of the Spencers’ firepower. Luckily for the cavalrymen, the Kickapoos either did not recognize or else failed to seize the opportunity before Frohock regained the cover of the fort.

Even so, the garrison still confronted a harrowing situation. The newcomers were driving a vast herd of captured livestock, and visible in their ranks were Hispanic and Anglo renegades, the hated Comancheros, who traded in stolen animals and white captive women and children with the hostile tribes of the region. The cavalry officer later claimed to have seen men clad in Confederate uniforms among the sinister company, but the presence of diehard Rebels in the ranks of such despised enemies of Texas was highly improbable. Frohock’s imagination did not inflate the size of the assembled enemy force, however. ‘Large parties now appeared upon the surrounding hills and coming up the canons [sic],’ he recorded. ‘Two-thirds of them were dismounted. Every disposition indicated a simultaneous attack from all sides to have been intended; but after the stampede of the horses, their object seemed accomplished and the Indians upon the hillsides and in the valleys south and west of camp made no further demonstrations, although several hundreds appeared in full view.’

The best chance for overrunning the troopers had passed, and most of Company K was now assembled behind the rock and adobe walls of the remaining structures. The Kickapoos and their criminal cohorts had captured 38 horses and mules that day, and they reckoned that there was little more of great value to be gained in charging into the muzzles of 40-odd Spencer carbines. The threat against the post receded, and even though Sergeant Underwood’s squad pursued the retiring southern war party and captured herd for four miles below the fort, the Indians did not try to cut off and annihilate his lonely squad of troopers. As night fell and their ammunition ran low, Underwood and his men returned to the garrison.

The horde of Indians menaced the post until dark and then moved on. In the morning, the countryside was devoid of Kickapoos. The battered command sought the bodies of Sharpe and the missing herders, which were not recovered for months. Two slain Indians were found on the field, and it was later estimated that the defenders may have killed as many as 20 while wounding many more. The troops recovered bows and quivers of arrows, personal effects, a Remington revolver, a new government-issue infantry overcoat. Also found was ‘a magnificent headdress with 20 silver plates which was dropped by the Indian that a corporal shot,’ boasted an officer who visited the post soon after the action. ‘I have no doubt but what he was the chief.’

Two days after the Battle of Fort Lancaster, some of the raiders returned to the area and made another effort to capture the few remaining animals held by the troops and the stage company. That effort failed, and the Indians moved southward down the Pecos. They would never challenge the outpost at Fort Lancaster again. Company K had once again proved too tough an opponent to be overcome, and Captain Frohock was well pleased. ‘The enlisted men, especially the non-commissioned officers, behaved gallantly,’ he noted. Lieutenant Smith ‘not only seconded my endeavors to save us the horses to the utmost, but led the charge of the skirmish line against overwhelming odds regardless of personal exposure.’ Certainly plaudits were due to the two ladies of the garrison, who earned their spurs by keeping the men supplied with cartridges.

‘The fight at Fort Lancaster proved the virtues of hard work, discipline, and a sense of purpose, and should have removed any doubts concerning the combat effectiveness of the Ninth’s black troopers,’ wrote one historian of the regiment nearly a century after the fight on Live Oak Creek. Whatever evils of indiscipline, dissension and mistrust had plagued the unit at San Pedro Springs nine months previously, these were nowhere in evidence on December 26, 1867, when prompt obedience, firm command, unit cohesion and lethal determination held the line against staggering odds. Although Captain Frohock might be faulted for failing to have an observation post established on the nearby high ground to give warning of just such an attacking force’s approach, he and his subordinates had responded with the steadiness and courage of veterans. After the fight at Fort Lancaster the 9th Cavalry ceased carrying the burden of scandal and began burnishing an emergent legend of duty and sacrifice for the Army and the nation.

The young captain continued to perform his routine duties with Company K until January 11, 1870, when he found himself facing court-martial charges. It was alleged that he was guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer for a February 1868 incident in which he had engaged in a game of poker with a civilian, a stagecoach driver. Frohock had allegedly lost heavily and tried to renege on his gambling debts until the angry reinsman forced him to settle his losses at gunpoint. Frohock was found guilty.

The sentence was routinely reviewed by higher authorities in the chain of command, who saw fit to reverse the verdict, ruling that Captain Frohock should be restored to duty. Seemingly reprieved from disgrace, Frohock instead chose to resign his commission. Colonel Edward Hatch, the regimental commander, subsequently claimed that Frohock had also gambled with his own troops and the civilian employees of the regiment. Upon resigning, Frohock also allegedly ‘raffled off his effects among the men of the company and gambled in their presence with these employees.’ Since Frohock was no longer a commissioned officer at the time of at least one of these supposed offenses, it is difficult to see how Hatch could cite them as lapses in professional conduct.

Captain Frohock’s departure from the 9th Cavalry under such circumstances raised several questions. Gambling with the stage driver was not illegal or unprofessional, although attempting to renege on a debt was definitely ‘conduct unbecoming.’ Still, no less a figure than Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer routinely gambled with his subordinate officers in the 7th Cavalry and was accused of ‘welshing’ on his losses by at least one of them, thereby creating a rift among the unit’s officers that endured until the Battle of the Little Bighorn. No one ever filed charges against Custer for such conduct. Lieutenant Edward M. Heyl, who was drunk on duty and whose murderous assault upon his own troops with a revolver provoked the San Pedro Springs mutiny, never faced charges for his misconduct and remained with the 9th until transferring to end his long career in the 4th Cavalry.

It seems that Frohock had, for whatever reasons, incurred the enduring hostility of his seniors in the regiment. If he did gamble with his own troops and government employees under his supervision, he assuredly should have been censured. Even so, the suspicion lingers that there was more to the situation than meets the eye at the distance of 135 years. The scandal-tinged officer re-entered civilian life and died in obscurity on April 10, 1878.

His able subaltern, Lieutenant Frederick W. Smith, faced an even crueler destiny. A Massachusetts native, he survived enlisted service in two Bay State infantry regiments before winning a lieutenant’s commission in the 1st U.S. Colored Cavalry on November 5, 1863. His honorable service with that unit won him a Regular Army commission in the 9th Cavalry in July 1866. Despite a rocky start in aiding in the suppression of the March 1867 mutiny in the unit’s San Antonio encampment, Smith settled in to weather the rigors of frontier soldiering and displayed admirable coolness under fire in the fight at Fort Lancaster that December.

Company K was subsequently transferred eastward to Fort McKavett, where the post commander was the stern and duty-bound Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie of the 24th Infantry, another black regiment. Showing much promise as an officer, Smith led frequent scouts against hostile Indians and white brigands, reportedly building a solid reputation with his superiors. But barely two years after the fight at Fort Lancaster, his world began to fall apart. First came allegations that he had mishandled government property. Then, on December 22, 1869, his wife announced that she was leaving him. Smith pleaded with her to reconsider, but she remained adamant over the separation. An hour before sunset he confronted his wife again and fired a pistol bullet into his brain. He took the reason for the breach in their marriage with him to his grave.

Frequent Wild West contributor Wayne R. Austerman is the command historian at the U.S. Army Medical Department Center and School at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. Suggested for further reading: Buffalo Soldiers and Officers of the Ninth Cavalry 1867-1898: Black & White Together, by Charles L. Kenner; The Buffalo Soldiers, by William H. Leckie; and The Kickapoos: Lords of the Middle Border, by Arrell M. Gibson.

This article originally appeared in the February 2005 issue of Wild West.