In Detroit in 2007, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ceremonially buried the word “n——.” But “n——” remains very much alive. In a June 2015 interview, President Barack Obama spoke the word to argue that racism remains a major problem whether or not “n——” is used in public. Three months later, an episode of the ABC sitcom Black-ish portrayed an elementary school with zero tolerance for hate speech moving to expel a first grader who, in a talent show, innocently performs Kanye West’s “Gold Digger.” In May 2016, Nightly Show host Larry Wilmore, appearing at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, ended his routine by affectionately referring to the president as “my nigga.” Afterward the men embraced. A furor ensued.

“N——’s” resiliency stems in large part from the term’s protean nature. Of course, the word can be a slur; that is its claim to infamy. But it’s also a term of endearment, a gesture of solidarity, a linguistic boomerang, a mirror to shame racists, a technique for cultural exclusion, a booby-trap, and a provocation—all aspects of a long and fractious history.

This chameleon-like word elicits kaleidoscopic reactions. Christopher Darden, who unsuccessfully prosecuted O.J. Simpson for murder, famously denounced “n——” as the “filthiest, dirtiest, nastiest word in the English language,” whereas Claude Brown, author of Manchild in the Promised Land, said “n——” was “perhaps the most soulful word in the world.” Poet Langston Hughes said in 1940 that “the word ‘n——’ to a colored person is like a red rag to a bull. Used rightly or wrongly, ironically or seriously, of necessity for the sake of realism, or impishly for the sake of comedy[,] it doesn’t matter…The word ‘n——,’ you see, sums up for us who are colored all the bitter years of insult and struggle in America.” Yet when black people use the word among themselves, writer Clarence Major noted, “n——” has “undertones of warmth and good will—reflecting…a tragicomic sensibility that is aware of black history.”

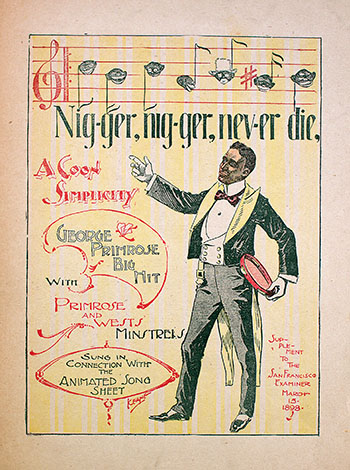

Etymologists trace “n——” to the 17th century and the Latin niger, meaning black. Though perhaps not originally an insult, by the early 19th century it certainly was. In 1837, black writer Hosea Easton called “n——” “an opprobrious term…It flows from the fountain of purpose to injure.” Easton, a minister and abolitionist, observed that white parents reprimanded offspring for being “worse than n——s,” “ignorant as n——s,” or for having “no more credit than n——s” and discouraged bad behavior by telling children that if they kept acting up they would be carried off by “the old n——,” made to sit with “n——s,” or be consigned shamefully to the “n—— seat.”

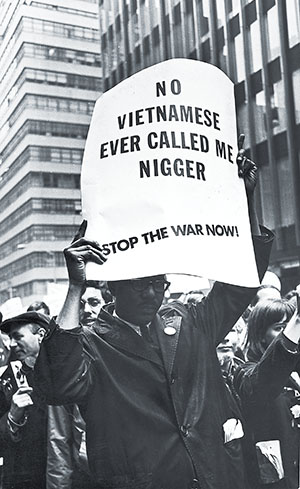

In a lexicon pockmarked with slurs—“kike,” “wop,” “gook,” “chink,” and “wetback,” to list a few—“n——r” has emerged as the ur-epithet which begets epithets. Arabs are labeled “sand n——s,” Irish “the n——s of Europe,” Palestinians “the n——s of the Middle East,” Native Americans “timber n——s.” The adjectival form almost always evinces contempt: “n—— eggs” (bowling balls), “n—— hams” (watermelons), “n—— heaven” (theater balcony). A disreputable ancestor? “The n—— in the woodpile.”

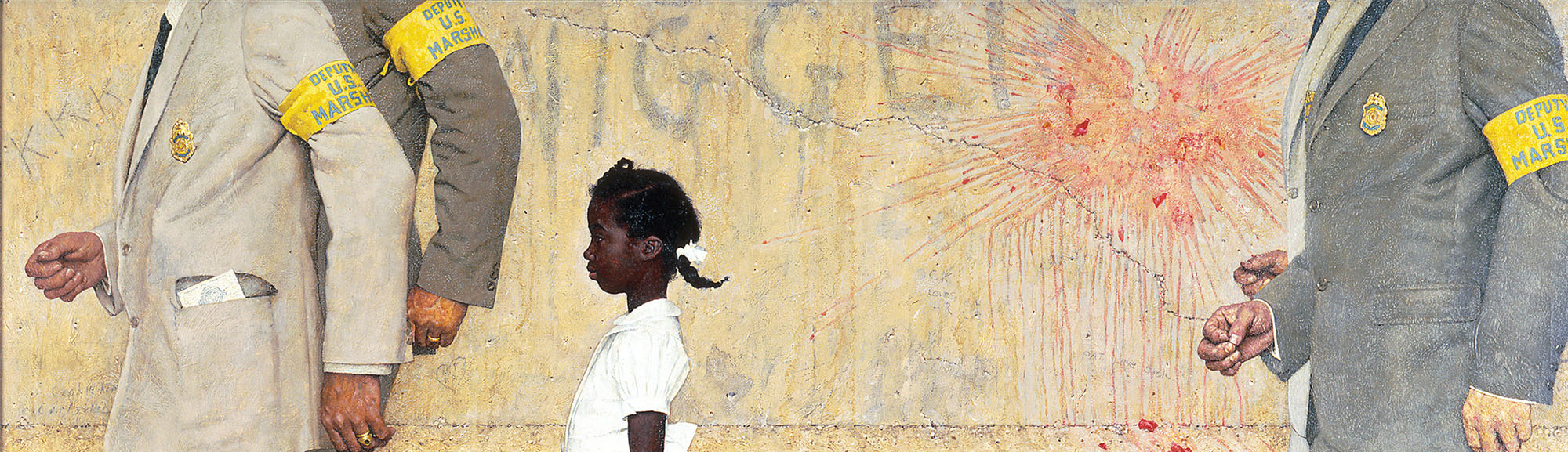

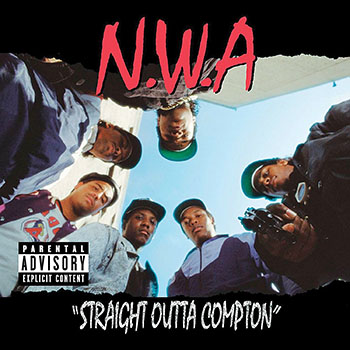

“N——” has seeped into every American cultural pore, from nursery rhymes: “Eeny-meeny-miney-mo! / Catch a n—— by the toe! / If he hollers, let him go! / Eeny-meeny-miney-mo!” to memoir: N——: An Autobiography, by Dick Gregory. The N-word appears in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn 215 times, and runs through popular music. Early 20th century songs reflect that era’s casual racism: “Who’s Dat Nigga Dar A-Peepin?” “Run, N——, Run,” “N—— Will Be N——,” and “He’s Just a N——.” A century later, the table has turned, with rappers, predominantly black, repurposing the N-word in tracks like “Niggaz 4 Life,” by N.W.A. (short for Niggaz With Attitude); “Niggas Bleed,” by The Notorious B.I.G.; and “Niggas in Paris,” by Jay Z and Kanye West.

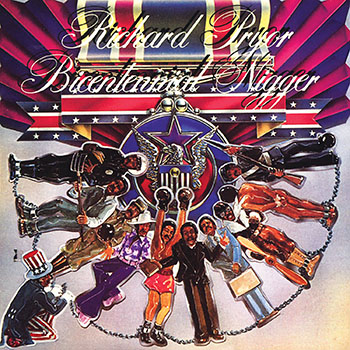

“N——” also goes to the movies—consider Training Day, Twelve Years a Slave, or any Spike Lee or Quentin Tarantino film—and has become a staple of stand-up. In That N——’s Crazy (1974) and Bicentennial N—— (1976), Richard Pryor produced sardonic and hilarious explorations of black American life anticipating Dave Chappelle, Chris Rock, Katwt Williams, Robin Harris, Martin Lawrence, D.L. Hughley, Bernie Mac, and many other black comedians.

“N——” has shown up in American politicians’ mouths at every level. Told in 1901 that Booker T. Washington had dined at the White House with President Theodore Roosevelt, Democratic Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina blanched. “Entertaining that n—— will necessitate our killing a thousand n——s in the South before they will learn their place again,” Tillman declared. Supreme Court Justice James Clark McReynolds is said to have referred to Howard University as the “n—— university.” Senator Lyndon B. Johnson once remarked that he talked everything over with his wife. “Of course…I have a n—— maid, and I talk my problems over with her, too,” he added. As president, Johnson continued to sprinkle his speech with “n——.” About to nominate Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court, the Texan reveled in Marshall’s well-known negritude.

“When I appoint a n——,” LBJ declared, “I want everyone to know he’s a n——.”

Richard M. Nixon has the dubious distinction of being the last American president on record using the N-word at the White House in the old-fashioned racist manner. During a phone conversation taped at his own order, Nixon had to soothe an irate Henry Kissinger. The president’s national security adviser was raging enviously about the good press Secretary of State William Rogers was enjoying on a trip to Africa. “Henry, let’s leave the n——s to Bill,” Nixon said. “We’ll take care of the rest of the world.”

Sociologist Elijah Anderson has written, “There comes a time in the life of every African-American when he or she is powerfully reminded of his or her putative place as a black person.” Anderson refers to it as the “n—— moment.” Poet Countee Cullen knew the feeling. In “Incident,” Cullen, recalling his Baltimore childhood, rendered in verse an exchange with another youngster: “Now I was eight and very small, / And he was no whit bigger, / And so I smiled, but he poked out / His tongue, and called me ‘N——.’”

Playwright August Wilson said he stopped going to elementary school for a while after white classmates left notes reading “Go home n——” in his desk. Basketball superstar Michael Jordan recalls school administrators suspending him for hitting a white girl who called him “n——” in a fight over a school bus seat. Golf great Tiger Woods remembers older kindergarten classmates tying him up and calling him “n——.”

In The Princeton Alumni Weekly, best-selling author Lawrence Graham wrote in 2004 of “the moment that every black fears: the day their child is called n——.” He described how his son, 15, phoned him from “a leafy New England boarding school” to report that two white men had stopped their car and menacingly asked young Graham whether he was the “only n——” at the institution. His father, an attorney, said school officials pooh-poohed the encounter as the kind of thing that “just happens.” Graham felt far differently, experiencing a pained sense of the limits of his capacity to protect his child.

In America, anything of significance lands in court, including words. “N——” has figured in hundreds of trials. In 1994-95, prosecutors in Los Angeles were seeking to prove that former football star O.J. Simpson had committed a double murder. A key prosecution witness, Los Angeles Police Department Detective Mark Fuhrman, testified that he had found incriminating evidence traceable to Simpson. Seeking to discredit the lawman, defense attorneys moved to let jurors know the detective habitually reviled blacks as “n——s.” Prosecutors urged the judge to exclude Fuhrman’s choice of language because awareness of it would “blind [the jury] to the truth” and “impair their ability to be fair and impartial.” Fuhrman denied the accusation but caught himself in a lie; recordings established that he did use “n——” frequently and with relish. Arguing that Fuhrman exhibited both racism and dishonesty, Simpson’s attorneys won a controversial acquittal.

The N-word has surfaced in scores of criminal cases. One hears it from Paul Warner Powell, a Virginia man who killed a woman and raped her younger sister, 14, reportedly out of rage at the older sister’s romantic involvement with a “n——.” One hears it from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, police officers convicted of brutally beating, torturing, and taunting (“N——, shut up, it’s our world”) two men of color who had accompanied two white women to a party. One hears it from Donald Middlebrooks, who, at least in part out of racial animus, stabbed to death a 14-year-old black boy in East Nashville, Tennessee.

When I published N——: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word in 2002, I maintained that major institutions of American life were handling the N-word about right, repressing it in most serious settings, particularly electoral politics, but permitting its use in art, entertainment, and casual settings among intimates employing the word in its ironic or friendly guises. That stance struck some readers as far too permissive. Nothing I have written has been more harshly denounced than my little book on the N-word. I think, though, that I was correct, descriptively and prescriptively. Consider politics: Only a wildly imprudent candidate would let slip the infamous term. George W. Bush could be overheard calling a New York Times reporter an “asshole” and win the presidency, but if that eavesdropped insult had been “n——,” there is no way Bush would have won.

Sensitivities have rendered the N-word untouchable farther down the political ladder, too. In March 2014, Robert Copeland, the police commissioner of Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, was chatting at a restaurant when he referred to President Obama as a “n——.” A diner nearby overheard and complained to town authorities. Copeland admitted the slur but initially refused to apologize. His stubbornness loosed a tide of denunciation, and within weeks he was gone.

Ostracism has greeted celebrities who violate N-word decorum. Performing at a comedy club, Seinfeld cast member Michael Richards called hecklers “n——rs.” Later he apologized profusely amid continuing condemnation and ridicule. In 2007, reality TV star Duane “Dog” Chapman, aka “The Bounty Hunter,” rode the N-word into public relations purgatory courtesy of an eavesdropper. In a phone conversation, Chapman excoriated his son for having a black girlfriend. He didn’t care about her race, the father said, he just feared she might hear him and his associates saying “n——,” as they were wont to do, and blow the whistle. His son’s relationship was putting him in danger of “some fucking n——” revealing how he talked, “Dog” said, unaware that a third party was recording the exchange and would soon make it public. When a black listener phoned radio personality Dr. Laura Schlesinger for help dealing with her white husband’s racist relatives, the caller complained about her in-laws’ use of the N-word. “Black guys use it all the time,” Schlesinger replied. “Turn on HBO, listen to a black comic, and all you hear is ‘N——, n——, n——.’” Negative reaction, swift and strong, figured in Schlesinger’s move to another broadcast outlet. An N-storm enveloped celebrity chef Paula Deen when she admitted that she had called blacks “n——s.” Deen’s cookbook sales soared, but Food Network, Walmart, Target, QVC, The Home Depot, and other companies that had had endorsement deals with Deen dropped her like a hot skillet.

These and similar episodes do not satisfy foes who want “n—— erased from the planet as an obscene, demeaning, destructive symbol. Eradicationists deny that the N-word can have a nonracist, non-insulting use. “Truth number one: No matter what color you are, no one can give you a pass to say the word. Not once, not ever,” maintains television journalist Bryant Gumbel. “Truth number two: Be smart. Using the N-word says a lot about you and none of it is good. It just advertises your ignorance. Truth number three: Pronouncing it with an ‘a’ after the ‘double g’ in the word because you’re with your boys makes you no more ‘with it’ than the clown who pronounces it with the ‘-er.’ Truth number four: Being young is not an excuse. The word’s use as a weapon to define, demean and destroy millions of people should never be forgotten.”

Unfortunately for eradicationists, millions of people, many of them black, routinely use “n——”—or “nigga”—as a salutation addressees perceive as friendly or, at least, acceptable. Conditional acceptance by blacks of the N-word is perhaps the greatest obstacle to eradication. After all, how can a word be invariably racist and insulting if many of the very people the term supposedly victimizes casually, even amiably, bandy it about?

But conceding that “n——” is not always objectionable points up a vexatious problem: determining when the N-word is and is not intolerable. In an instance in Chicago with overtones of the fictional Black-ish episode, a teacher at a public middle school heard students arguing. The children were discussing a note that quoted rap lyrics that included “n——” or a variant. According to a court document, the teacher “decided to defuse the situation by explaining the controversial use of the ‘N’ word in rap music and society at large. [The teacher] explained that the word ‘n——’ was distasteful and historically offensive to African-Americans and that the use of that word by some African-Americans is viewed with disgust by others.” Witnessing some of the classroom discussion, the principal suspended the teacher for five days without pay, citing a systemwide ban on use of “verbally abusive language to or in front of [a] student.” But was that teacher engaging in verbal abuse? Or was he seizing a teachable moment, creatively educating his pupils about a tricky, volatile subject highly relevant in their lives—and one the students already were talking about? Was the teacher even “using” the N-word, or was he simply quoting its use for pedagogical purposes?

Emblematic of “n——’s” strange career and fraught future is controversy that periodically engulfs the National Football League. In 2015, wide receiver Riley Cooper of the Philadelphia Eagles was videotaped at a Kenny Chesney concert using “n——” in its historically ugly form. That same year, Washington Redskins lineman Trent Williams and referee Roy Ellison got into a dispute. Ellison called Williams “n——.” Both men are African-American.

Those fracases were still fresh when Richie Incognito, a white guard for the Miami Dolphins, taunted tackle Jonathan Martin, calling his black teammate “n——.” Incognito’s widely condemned conduct became a key element in the argument that the NFL needs to enforce minimal standards of decency. In 2014, the Fritz Pollard Alliance, a group that promotes racial equity in the league, urged a ban on “n——,” with severe sanctions for violations. The proposal attracted both support and opposition. Richard Sherman, an outstanding Stanford-educated cornerback who is black, said a ban would be “almost racist,” since the word’s main users are black, and strict-constructionist enforcement would fall disproportionately on African-American players.

Other objections included complaints that the NFL lacks standing to punish use of the word “n——” because one of its teams calls itself “Redskins”—a term many regard as deeply racist. Others, echoing Sherman, said that wide use of “n——” as a salutation, especially among young black men, would bring intrusive policing, alienating players and fans. The NFL shelved talk of a new rule, suggesting an existing ban on “offensive conduct” be read to include malevolent use of “n——.”

Despite the abhorrence any use of “n——” inspires in many, it’s folly to try to stamp out the word. The repression required to achieve obliteration would impose costs far exceeding the benefits. Eradicationists insist that the N-word is unchangeable, but, as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. observed, every word is “the skin of a living thought [that] may vary greatly in color and content according to the circumstances and time in which it is used.” Or, as African-American author Ta-Nehisi Coates has written, “When people claim that the word ‘n—— must necessarily mean the same thing, at all times spoken by all people, one wonders whether they understand how the very words coming out of their mouths actually work.”

Ignoring how marginalized groups relate to the very language that is employed to marginalize them, eradicationists disdain black folks’ efforts to redeploy “n——” on their own behalf to subvert its power. White Washington Post sports columnist Mike Wise scoffed that he knows of “no other minority in the world co-opting a dehumanizing racial slur used by its oppressor.” Wise is wrong. Many marginalized groups spin slurs their way. Native Americans play with the term “skins.” Jews joke about “Hebes.” Women have recast “bitch” as an accolade, and gays have made “faggot” their own.

“N——,” thank goodness, simply ain’t what it used to be. Once, even prominent figures could use it without apprehension—and racists still sling those syllables to draw psychic blood. But the “n——” of racist habit is a shadow of its former ugly self, and withholding government censorship for even ugly enunciations of the word is an acceptable price for the freedom and innovation that toleration permits. I believe that for bad and for good, “n——” is destined to remain with us, a reminder of the ironies, dilemmas, tragedies, and glories of the American experience.