Alexander von Falkenhausen led Turks against the British and Chinese Nationalists against the Japanese, spared Belgian hostages and conspired in Adolf Hitler’s assassination

Jonathan Fenby, Chiang Kai-shek’s British biographer, called Alexander von Falkenhausen “a First World War veteran with a vulturelike head and pince-nez.” Historian Barbara Tuchman described Falkenhausen as a skilled commander who led from the front but got nowhere with Chiang, who was the villain in her biography of American Gen. Joseph Stilwell. In 1953 Chiang, by then president of the Republic of China on Taiwan, sent Falkenhausen 75th birthday wishes and an enclosed check for $12,000 (more than $120,000 in today’s dollars). But it was a Chinese woman named Qian Xiuling, “China’s female Schindler,” who helped Falkenhausen—a hero in China and a villain in Belgium—beat a 12-year prison sentence as a Nazi war criminal.

Falkenhausen seemed destined for controversy long before his birth. Genealogy establishes him as a descendant of Karl Wilhelm Friedrich, margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, by his mistress, Elisabeth Wünsch, making Falkenhausen a distant member of the Prussian royal family.

The future general himself was born on Oct. 29, 1878, in Blumenthal, Silesia, to Baron Alexander von Falkenhausen and wife Elisabeth (née Schuler von Senden). The second of seven children and son of a baronial family, young Alexander initially attended a Gymnasium (classical secondary school) in Breslau but at age 12 transferred to the military academy at Wahlstatt as a cadet. In 1897 the teenager was assigned to an Oldenburg infantry regiment as a second lieutenant. When the Boxer Rebellion broke out in 1900, Falkenhausen volunteered and was sent to China. Most of the fighting was over by the time he arrived, but he developed a lifelong fascination with both China and Japan.

In 1904, while teaching at the Prussian military academy, Falkenhausen married Sophie von Wedderkop, the daughter of a military commander from Oldenburg’s hereditary dynasty. In the wake of the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War the German General Staff showed a growing interest in Japan’s military potential. Falkenhausen was seconded to the General Staff and spent 18 months studying the sometimes maddeningly imprecise Japanese language and parsing diplomatic reports on Japan, China and Korea. In 1912, after promotions to senior lieutenant and then captain, he was appointed a military attaché in Tokyo.

In August 1914 Japan, a formal ally of Britain since 1902, declared war on Germany and took over the Shandong Peninsula, which the Germans had leased under treaty from China since 1898 and turned into their largest overseas naval base. The German military staff in Tokyo was recalled, and by November 1914 Falkenhausen was serving as a major on the Western Front. He later transferred to the Eastern Front.

In 1916 Falkenhausen joined the German military mission to Turkey, an assignment requiring the utmost tact. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s primary military commander in the Turkish army, Generalleutnant Otto Liman von Sanders, had viewed the Turkish “evacuation” (read genocide) of Armenians with horror and warned the Turks that if they touched a single Armenian soldier in his own command he would withdraw to Germany and take his men and ammunition with him. German diplomats and missionaries also protested the outrage. The Turks ultimately killed an estimated 1 million Armenians through outright murder, thirst or starvation. Falkenhausen arrived after the crisis abated and fought Russians in the Caucasus, then in 1917 was transferred to Palestine. As chief of staff of the 7th Ottoman Army he inflicted a series of temporary defeats on the British. When the Turks suggested that resident Jews in Palestine were British spies and proposed another “evacuation,” the German military officers objected, likely preventing another genocide.

Germans serving with the Turks could only hope to stave off collapse as long as possible. One trooper of the Australian Light Horse noted “how the Turk fights till the very last charge, until the pounding hooves are upon him, then he drops his rifle and runs screaming, while the Austrian artillerymen and German machine-gun teams often fight with their guns until they are bayoneted.” Wilhelm considered himself a protector of the Jews and appreciated Falkenhausen’s diplomacy as well as his leadership. In 1918 the kaiser awarded the major the Pour le Mérite, imperial Germany’s highest award for outstanding leadership in combat, and in the final weeks of the war Falkenhausen was made chief military adviser to Constantinople.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles the postwar German army was to be reduced to 100,000 men with 4,000 officers. Falkenhausen kept his job, and when navy Korvettenkapitän Hermann Ehrhardt refused to dissolve his 6,000-man Freikorps (free corps) marine brigade, the major was sent to the rebel’s guarded camp outside Münster to facilitate the unit’s peaceful disbandment. While the government had issued a warrant against Ehrhardt for high treason (despite his having signed orders from his superiors), the captain had promised his men that anyone not kept on in the much-reduced military would have a job before he himself left the brigade. His men refused to give him up—indeed, they wanted to march on Berlin.

“At my request, Major Falkenhausen took over as my chief of staff,” Ehrhardt later wrote. “He was exceptionally efficient. He worked not only with understanding, but also with his heart. I owe him my profound thanks.” Ehrhardt shaved off his beard and made himself scarce once Falkenhausen found his men jobs.

Falkenhausen also negotiated with the Poles to resolve border disputes after a 60–40 plebiscite vote allowed Weimar Germany to retain Upper Silesia. Many members of the Polish majority voted to remain German—perhaps due to concern about Soviet Russia—while some upper-class Germans voted to merge with Poland because the Weimar Republic was much further to the left than Gen. Józef Pilsudski’s militaristic government in Warsaw. The Poles were expected to respect inherited estates or large businesses. Giving all inhabitants (ethnic Germans and Poles alike) equal rights temporarily resolved the question.

The Nazi movement—even before Adolf Hitler came to power—was anathema to Falkenhausen. In 1930, when the Nazi Party urged then Generalleutnant Falkenhausen to join, he declined, yet the party newspaper crowed he had indeed signed up. The false report prompted the Weimar government to sack him, at which point leading Nazis suggested he join the paramilitary Sturmabteilung (SA) for a substantial salary increase. Falkenhausen again refused and instead joined the Stahlhelm, an anti-communist veterans’ group that made overtures to Jewish combat veterans and opposed Hitler’s dictatorial aspirations. Falkenhausen also joined the German National People’s Party, a conservative monarchist group that garnered about 10 percent of the popular vote and included senior officers, industrialists and aristocrats as supporters. By 1933 it had dissolved, opening the path to dictatorship.

“People accepted the incomprehensible misconception it would be possible merely to use Hitler as a ‘rallying drummer,’” Falkenhausen later recalled. “It was clear to me the coalition of the German Nationalists with the National Socialists could only be compared to the friendship of the defenseless lamb with the hungry wolf.” He stuck it out with the Stahlhelm until it federated with the SA during the Depression amid the growing fear of communism.

When Hitler came to power through the back door, Falkenhausen knew he was finished in German army politics. But then a door to the East opened: Chiang Kai-shek offered Falkenhausen command of his staff of German military advisers. After obtaining approval from senior commanders, the general moved to Nanjing. His new employer, Chiang, had transformed from something of a rebel in Manchu times into a hard-core anti-leftist who had purged communists and trade unionists in Nanjing and Shanghai in 1926–27 amid the brewing civil war. (Oft-reproduced photos of kneeling Chinese being shot by Chinese soldiers were presented falsely in Frank Capra’s 1944 documentary Why We Fight: The Battle of China and Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 epic The Last Emperor as depicting Japanese atrocities.) But no such atrocities happened on the German watch.

Falkenhausen’s own solution to communism was militaristic rather than terroristic. “China must resist in two ways: morally and materially,” he wrote.

Already advising Chiang was Generaloberst Hans von Seeckt, the monocled “Sphinx” who rebuilt the German army in the 1920s by turning the 100,000-man Reichswehr into a cadre to train officers and sergeants. Seeckt had been dumped by Hitler in 1926 ostensibly because the latter believed the general’s wife was of Jewish origin—though in fact she was of ethnic German origin, from Friesland, and she and her husband were anti-Semites. Seeckt’s real offense had been to allow Prince Wilhelm, grandson of the former emperor, to participate in army maneuvers. Hitler hated the Jews but feared the Prussian royals and their influence on the officer corps. By the time Seeckt arrived in China, he was dying of cancer. Before he returned to Germany for the last time in 1936, however, he and Falkenhausen made plans to drastically reduce the size of Chiang’s army to 60 well-trained divisions loyal only to Chiang, not to regional warlords. They also directed the generalissimo to erect thousands of blockhouses near communist strongpoints, to be garrisoned by stalwart troops with supplies dropped off by trucks so the communists could not raid lackluster government troops or peasants for food.

The 1937 Japanese invasion of China caught Falkenhausen unprepared, with only 80,000 trained Chinese troops in eight divisions, but he tried to exude a confidence he never actually felt. At Shanghai that fall he led his soldiers in person, and they put up a fight that astounded the world. “We [Germans] all agreed that as private citizens in Chinese employment there could be no question of leaving our Chinese friends to their fate,” he wrote. “Therefore, I assigned German advisers wherever they were needed, and that was often in the front lines.”

Everyone knew the Chinese would lose, but the fact they held up the Japanese for three months, and that some units fought virtually to the death, won them considerable respect. The survivors fell back on Nanjing, capital of the republic. Falkenhausen urged the Chinese to evacuate and declare Nanjing an open city, thus sparing it destruction under international law. Chiang decided to fight to the death to save face, then escaped by seaplane. When the Japanese broke through the city walls, some of the Chinese trained by Falkenhausen fought to the death. Others formally surrendered in full uniform after hard fighting.

In the aftermath the Japanese executed tens of thousands of soldiers and suspected troops in what has come to be known as the Nanjing Massacre. Japanese troops also engaged in widespread looting and rape. The international committee (comprising Americans, British, Germans and Danes) of the Nanjing Safety Zone investigated and signed off on 360 rapes and 41 murders of obvious civilians.

Appalled by the wanton killing and unpunished rapes, Falkenhausen subtly pointed out to the Chinese that Japanese officers were easily distinguished by their map cases, binoculars and samurai swords, and that a few Chinese snipers could do the Nationalist cause far more good than doomed last stands against Japanese artillery and tanks. German-trained Nationalist troops won a night attack against the Japanese at Taierzhuang in early 1938, but by that time Falkenhausen and his fellow advisers had been ordered home—reportedly under Nazi threat to their families—and Germany had signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan and Italy.

When war broke out with Britain and France in September 1939, Falkenhausen was recalled to duty by Nazi Germany. He was conflicted, for despite his dismay at Hitler’s policies, he remained firmly anti-communist. The following spring he followed in his uncle Ludwig von Falkenhausen’s footsteps when appointed military governor of Belgium and northern France. While Falkenhausen readily deported Belgian leftists as slave laborers to Germany, he tended to drag his feet where Jews were concerned.

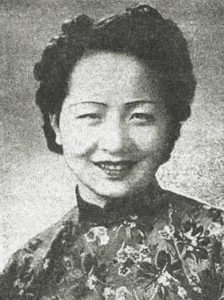

One “Belgian” who remembered Falkenhausen was Chinese-born Qian Xiuling, whose family members were influential friends of Chiang and whose cousin had served as a general under Falkenhausen’s oversight. A gifted student who had traveled to Belgium in 1929 to study advanced chemistry, Qian later broke her arranged engagement to a Chinese fiancé in order to marry Belgian physician Grégoire de Perlinghi in 1933. Her family reminded her Falkenhausen was a man who could be trusted. When members of the Belgian resistance killed three Gestapo officers in the town of Écaussinnes on July 7, 1944, in the tense wake of the D-Day landings, superiors in Berlin ordered the arrest of 97 random townsmen to be shot in retaliation. Qian, though expecting her first child, drove to Falkenhausen’s headquarters on a rainy night and pleaded with him to spare the hostages. She must have been persuasive, for the governor did exactly that, for which he was immediately summoned to Berlin and removed from command. Two weeks later he was again called on the carpet and immediately sent to Dachau.

Falkenhausen’s arrest had nothing to do with the Belgian hostage issue. He had been in contact with members of the failed July 20 plot to kill Hitler, having agreed in principle to place the German garrison in Belgium and northern France at their disposal while they sought to negotiate a separate peace with the Western Allies. Though not tried for lack of evidence, Falkenhausen spent the closing months of the war in various concentration camps. He was liberated by American soldiers on May 5, 1945, only to be promptly arrested by Belgian authorities as a war criminal. Belgian leftists pressured him to incriminate King Leopold III as a pro-Nazi collaborator, but Falkenhausen, a monarchist, flatly refused. For nearly six years he cooled his heels in a cell awaiting trial.

In 1951 Qian, by then a heroine of the Belgian resistance, showed up at 72-year-old Falkenhausen’s trial, producing Belgian witnesses to his act of mercy and words of praise from a grateful President Chiang. His defense attorney also pointed to the general’s known role in the July 20 plot. Though the court sentenced Falkenhausen to a dozen years of hard labor, it released him after three weeks, citing time served. “Ungrateful Belgium, you will not have my bones,” he proclaimed on crossing the border into Germany after his release. Childless after two marriages (his second to a Belgian resistance fighter he’d met in prison), Falkenhausen lived another 15 years, dying at age 87 on July 31, 1966.

For her part, Qian remained in Belgium and never returned to her homeland. She received a medal from a grateful Belgian government, was the central heroine of a 16-episode Chinese TV series and lived well into her 90s. Asked once by a Chinese reporter to describe Falkenhausen, she said simply, “He was a man with morals.” MH

A frequent contributor to Historynet publications, John Koster is the author of Hermann Ehrhardt: The Man Hitler Wasn’t, and Operation Snow. For further reading he recommends Falkenhausen’s own Mémoires d’Outre-Guerre, and Chiang Kai-shek: China’s Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost, by Jonathan Fenby.

This article appeared in the January 2022 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.