On the same day Alexander III of Macedonia was born in 356 bce, the famous temple of Artemis at Ephesus was destroyed by fire. The soothsayers wailed that somewhere in the world a torch had been lit that would consume all Asia. The portent proved true. Alexander swept into Asia like a devouring blaze whose intensity none could endure. As he surveyed the fortress city of Tyre, a high island of rock severed from the mainland by a deep, windswept channel, perhaps even he wondered if here the flame would be quenched.

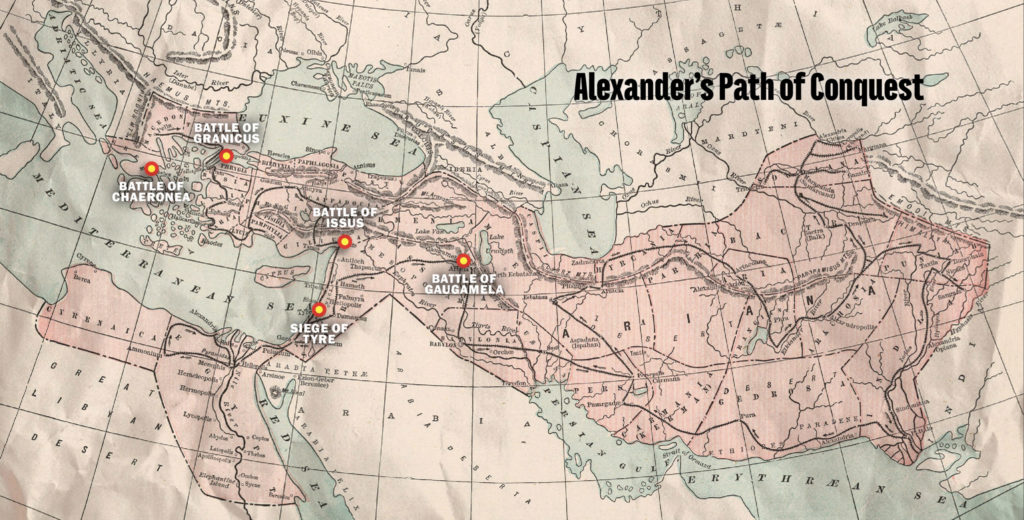

In the early spring of 334 BCE, Alexander marched to the Hellespont, the narrow strip of water dividing Europe from Asia. The strait was not only the most practical crossing place, it also held symbolic significance as the very passage taken by the Persian king Xerxes when he invaded Greece nearly 150 years before. The subsequent battles at Thermopylae (480 BCE), Salamis (480 BCE), and Plataea (479 BCE) were enshrined in Greek memory as imperishable monuments to the defense of freedom against despotism. Alexander sought such associations to support the claim that his conquest was a panhellenic crusade to avenge wrongs done to the Greeks by the Persians rather than a quest for personal gain or glory.

Yet Alexander’s status as an advocate of Greek freedom was problematic. He had commanded the left wing of the Macedonian army at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 bce) that destroyed the independence of the Greek city states. His father, Philip II, had united all the Greeks except the Spartans into a single federation called the League of Corinth. with himself as Hegemon. To place the final seal upon this unity, he put before the Federal Council his greatest project—a war against Persia. When Philip died, the Greeks rebelled against Macedonian rule. But the gifted father had a gifted son. Alexander quickly put down the rebellion and took for his own the powers of Hegemon and Captain-General of the League war against Persia. But even as he moved forward in their name, he had always to guard against an uprising of the rebellious Greeks.

Defying the Persian Empire

After Alexander won his first major victory against the Persians at the Granicus River (334 bce), he set about bringing Asia Minor under his control. The center piece of that project was liberating the Greeks who lived there, which strengthened his propaganda as well as serving a strategic purpose. Alexander could not safely proceed farther without leaving a stable political structure in his wake. He intended no mere hit-and run raid, but a steady, ordered conquest that replaced the rule of the Great King with his own.

He knew that the Persians ruled the Greek-inhabited cities through oligarchies hated by their subjects. By offering these cities freedom and self-determination, he was progressively undermining Persian control and securing a friendly country that would not have to be held in subjection with large garrisons.

The coastal cities were important. If those were won, the Persian navy would be deprived of its bases in the eastern Mediterranean, undermining its ability to interdict Alexander’s communications and supply—and allowing him to push farther inland. Knowing that victory over the Persians at sea was unlikely, Alexander disbanded most of his navy, committing himself to a land-based strategy.

After having secured Asia Minor, Alexander was again victorious at the battle at Issus (333 bce) in Hollow Syria. This time the Great King Darius III was himself present but fled the field as his army disintegrated under Alexander’s furious assault. Rather than pursue him toward the heart of the empire, Alexander continued his coastal strategy by marching south to Phoenicia. The Phoenicians were expert sailors, and their many coastal cities contributed a great number of ships to the Persian navy. Unwilling servants of the Persians, the cities of Marathos, Arados, Tripolis, Byblos, and Sidon surrendered to Alexander.

But the city of Tyre still lay in his path. Though it stood practically alone, it was strong and stubborn.

To Sack An Island City

As he approached Tyre, Alexander was met by envoys sent by the populace to declare they would do as he ordered. Pleased, Alexander told them to return and tell the Tyrians he wished to enter their city and sacrifice in the ancient temple of Heracles, as the Greeks named the Phoenician god Melkart. Alexander’s arrival in February of 332 bce corresponded with a great festival in honor of the god.

The prospect of Alexander’s participation and likely domination of the festival was viewed by the Tyrians as a direct challenge to their sovereignty and independence which they were unwilling to accept. They refused, returning word to Alexander that he was welcome to make his sacrifice at a sanctuary outside of the city, but that they would receive neither Persian nor Macedonian within their walls. In this war for an empire, the conqueror would not accept such a declaration of neutrality. He prepared to take the city by siege.

Alexander’s decision to besiege Tyre flowed from several strategic considerations. First, it would be damaging to his reputation as an invincible conqueror to leave behind any city that had successfully resisted him. Such a spark could easily ignite rebellions in the vast territory he had already conquered in Asia, binding him to the task of maintaining rather than extending his rule and encouraging resistance in those yet to face him. Such a failure would also embolden rebels in Greece, most notably the Spartans, but also Athens and every other city held in the League by fear rather than devotion.

Second, Tyre’s continued independence would undermine his coastal strategy to gain command of the sea. Left intact, Tyre would serve as a base and a rallying point for Persian naval forces. But with Tyre taken, he would advance his control of the coast and open the path to Egypt. He would no longer be shackled to the Mediterranean, allowing him to march inland where he might strike at the heart of the Persian Empire.

A Gamble?

Third, the fall of Tyre would complete the conquest of Phoenicia, the source of the largest and strongest contingent of the Persian navy. Those forces, he reasoned, would join with him because the Phoenician oarsmen and marines would not continue to serve the Persians while their cities were under his control.

This point indicates a reconsideration of Alexander’s neglect of naval forces. His earlier decision to disband the navy was risky and very nearly disastrous. In the year following, the Persian navy threatened to carry the war back into Europe. The Persians seized the island of Chios and all of Lesbos apart from the city of Mytilene, which they blockaded. There were even rumors of plans for an invasion of central Greece.

The risks inherent in Alexander’s decision to abandon his fleet had now become realities. With Persian successes in the northern Aegean, Alexander’s bridgehead at the Hellespont was endangered. In response, he commissioned a new fleet, but the Persians wrought havoc before it could be mobilized. Mytilene was captured along with Tenedos at the mouth of the Dardanelles, a mere thirty miles from the crossing point at Abydos.

Alexander was saved from possible disaster by his enemy. At that moment Darius decided to recall the bulk of his mercenary forces to Asia, depriving his fleet of manpower in preparation for a single, massive, pitched battle on land. In so doing, he abandoned the attack where Alexander was weakest to meet him where he was strongest. The outcomes of the battles of Issus (333 BCE) and Gaugamela (331 BCE) would reveal Darius’ fatal mistake.

Challenging Poseidon, God of the Sea

Alexander rarely relied upon strategic considerations alone when justifying an action or military operation. It is a prominent feature of his campaigns that he frequently sought favorable omens from the gods and desired to follow in the path of heroes. His first act when he entered Asia Minor was to travel to Troy where he sacrificed to Athena and evoked the champions of old by laying a wreath upon the tomb of Achilles.

Nor were foreign gods necessarily to be spurned. The Greeks often viewed the gods of the near east as local manifestations of their own gods, and they were willing to pay them devotion—hence, Alexander’s desire to sacrifice to the Tyrian Heracles. This easygoing polytheism played a prominent role in Alexander’s absorption of conquered peoples into a vast, multi-ethnic empire. His intention to take Tyre was fortified when he had, or claimed to have had, a dream in which Heracles led him by the hand into the city.

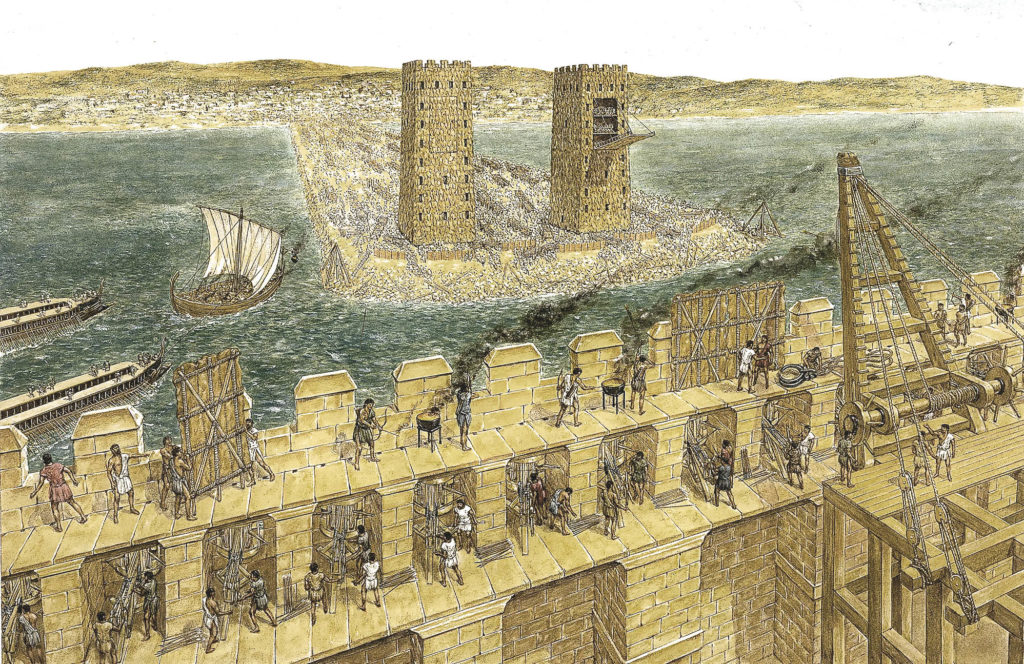

Set on an island protected by deep water patrolled by a strong fleet, its sheer, high walls defended by a skilled and resolute citizenry, Tyre’s capture would be no easy task. Daunted by neither man nor nature, Alexander’s plan was to bridge the gap between the city and the mainland by building a causeway. His siege engineers packed rocks between piles driven into the mud, which served as cement, and covered this foundation with beams of timber gathered from the forests of Lebanon. He secured an abundance of stone by demolishing Old Tyre on the mainland, and the project initially proceeded rapidly under Alexander’s personal direction.

At first the Tyrians ridiculed this ambitious project, jeering at the soldiers carrying loads on their backs like beasts, and mocking Alexander’s arrogance for daring to challenge Poseidon, god of the sea. But, increasingly disturbed by the swift progress of the work, they began to construct extra mechanical artillery and strengthen their defenses.

The Two Towers

When the causeway left the shallows behind and began to approach the city itself, the workers came within range of missiles and arrows from the wall as well as being harassed by triremes sent out to hinder them. Dressed for work rather than combat, they suffered badly under these attacks.

To counteract these dangers, Alexander ordered two towers built on the edge of the causeway. Screened with skins and hides to defend against flaming darts, mounted with siege engines (such as catapults), and manned by archers, the towers proved a successful countermeasure.

Thwarted by the towers, the Tyrians changed their tactics. They loaded a cavalry transport ship with the greatest amount of burnable material it would hold mixed with pitch, tar, and sulfur to encourage combustion. Cauldrons of naphtha were hung from the yardarm where these accelerants would fall on the burning material below. The stern was weighted with ballast to raise the bow so that it would carry up onto the causeway. Waiting for a favorable wind, they then towed the fire ship forward with triremes, increasing their speed as they approached so that, when released, its momentum would carry it forward.

At the last moment, those aboard set the pile alight and jumped over the side. Lodging firmly on the causeway near the towers, the ship became a furious conflagration when the yardarm burned through, dumping the naphtha onto the hungry flames. The siege towers became pillars of fire. Seizing the moment, many small ships from the city landed on the causeway, tearing down the protective palisade and destroying the siege engines the fire had not consumed. There is no record of Alexander’s reaction to this thwarting of many long months of effort. We only know that he began again with an improved plan.

While the new causeway, now wider and guarded by more towers, was being constructed, Alexander’s prediction began to come true. Geostratos, the king of Arados, along with Enylos of Byblos, learning that their cities were in Alexander’s hands, sailed to join him. Their example was soon followed by ships from Rhodes, Cilicia, Cyprus and Sidon. News of Darius’ defeat at Issus and Alexander’s control of Phoenicia was causing the disintegration of the Persian fleet.

Engines and Flaming Arrows

When all of these kings and captains had sailed to him, Alexander pardoned them for past offences on the grounds that they had served with the Persians under duress rather than by choice. He now had a fleet of 220 warships at his disposal, a force greater than the Tyrian navy. He was also reinforced with nearly four thousand Greek mercenaries from the Peloponnese.

Having gathered the fleet at Sidon, Alexander sailed to Tyre, hoping the Tyrians would engage him in a sea battle. But, alarmed by the unexpectedly large number of ships, they adopted a defensive posture, blocking the entrance to their harbors with triremes. Disappointed, Alexander anchored his fleet along the shore near the causeway. The next day he ordered the Cyprians to blockade the Sidonian harbor in the north of the island and the Phoenicians to guard the southern Egyptian harbor on the other side of the causeway. Now the attack on Tyre transformed into the unusual spectacle of a water-borne siege.

Alexander put engineers from Cyprus and all over Phoenicia to work building engines of war mounted on ships. With rams and catapults, Alexander tested various sections of the wall, probing for a weak spot, while the Tyrians attempted to halt their efforts by launching flaming arrows, sending out divers to cut anchor cords, and littering the water with obstacles.

When the Macedonians countered these measures by securing their anchors with chains rather than cords, roofing and fireproofing the ram ships, and clearing the obstacles from several approaches to the walls, the Tyrians had little choice but to attempt an attack by sea. For several days, they concealed their preparations behind a screen of unfurled sails stretching across the mouth of the Sidonian harbor. They assembled their most powerful ships and manned them with their best crews and finest marines.

A Surprise Counterattack

The timing of their attack was planned carefully to maximize the chances of success. The Tyrians had observed that many of the crews of the blockading Cyprian ships withdrew to the mainland around noon for their midday meal. At this same time, Alexander, who was usually with the Phoenician fleet, withdrew to his tent to eat and rest.

Seizing the opportunity, the Tyrians launched their surprise sortie. Initially, the attack was very successful. Many of the ships were empty or nearly so. They sank several and drove others on to the beach to smash them apart. Unfortunately for the Tyrians, Alexander changed his habits that day and rejoined the Phoenician fleet earlier than usual. When news of the attack reached him, he was in position to react immediately. Ordering part of the fleet to guard the southern harbor against a similar breakout, he sailed around the island with five triremes and several other warships to support the Cyprian fleet.

Observing this action from the walls, the Tyrians within the city tried frantically to signal their fleet to withdraw. In the tumult of combat, their warnings were unheeded by the Tyrian crews until Alexander was nearly upon them. Several Tyrian ships were destroyed and others captured as they attempted to reach the safety of the harbor. The only consolation they could grasp was that most crews were able to swim to safety. Siege engines continued to batter the fortifications. Eventually a section of the southern wall crumbled.

The final assault of Tyre began. Transport ships fitted with gangways sailed toward the breach while triremes were stationed at the harbors to prevent another breakout. When the gangways dropped, the Macedonians poured forth onto the wall, Alexander himself among the foremost.

Alexander in the Thick of Combat

Alexander’s active role in combat was a consistent element in his campaigns. He exercised heroic command. Not only was he present on the battlefield, he fought in the front lines at great personal hazard. Again and again, Alexander led the charge of the Companion Cavalry and was among the first to scale the walls of a besieged fortress.

The list of his wounds tells the tale of his command style. At the Granicus, Alexander’s helmet was cleft through to the scalp; at the Battle of Issus, he suffered a sword wound in the thigh; at Gaza he was hit by a missile from a catapult that passed through his shield and breastplate and struck his shoulder; at Maracanda in Sogdiana, an arrow pierced his leg fracturing the fibula; later in that same year, while besieging a fortified town on the Iaxartes River, he was struck by a stone on the head and neck; in western India he received wounds in the shoulder and ankle; and an arrow punctured his lung while he was attacking a city of the Malli in India. It was with justification that he would chide the mutineers at Opis that there was no part of his body but his back that did not bear a scar.

After a fierce battle on the wall, the Macedonians descended into the city itself. At the same time, Alexander’s naval forces broke through the blockades in both harbors, destroying the enemy ships and landing troops on shore. A great slaughter followed. Pockets of resistance within the city were wiped out with ferocity. The Macedonians were in a rage and, after the frustration and casualties of a seven-month siege, in no mood to show mercy. The blood of 8,000 Tyrians stained their island city red.

When the butchery had ceased, Alexander walked through the blood and the smoke to the temple, where he made his long-delayed sacrifice. Alexander reinforced the lesson of the futility of resistance through further penalties.

Granting amnesty to all who had fled to the shrine of Heracles, including the king of Tyre and ambassadors from Carthage, he sold 30,000 others, mainly women and children, into slavery. According to some ancient historians, Alexander also ordered the crucifixion of some 2,000 remaining military-aged males along the shore.

The message conveyed by this grisly ornamentation could hardly be missed. Tyre became a stronghold of the growing Alexandrian empire.