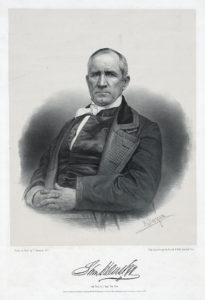

Word of the slaughter of the Alamo garrison filtered quickly through the Texian camp on the Guadalupe River at Gonzales in March 1836. On the morning of the 13th, frustrated by the uncertainty of intelligence brought by two Mexican vaqueros, General Sam Houston of the Army of the Republic of Texas sent scouts Erastus “Deaf” Smith, Henry Wax Karnes and Robert Eden Handy riding toward San Antonio de Béxar to ascertain the truth.

The riders returned after nightfall with others bearing news that triggered shock waves across the Texas frontier and into the United States. A dozen miles out on the road to San Antonio the trio had encountered a weary band of Alamo refugees—Susanna Dickinson, the widow of artilleryman Almeron Dickinson, carrying the couple’s infant daughter, Angelina; Joe, the teen slave of Alamo co-commander Lt. Col. William Barret Travis; and Ben Harris, Mexican army Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte’s cook, whom the colonel had sent along as an escort. The scouts brought the trio to Houston’s tent, where they confirmed the general’s worst fears.

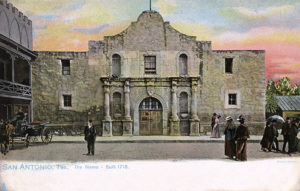

On the morning of March 6, following a 13-day siege, the army of Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna had overrun the undermanned Alamo garrison. The gallant defenders had fought fiercely to the last man. Santa Anna had then ordered the Texian dead stacked between layers of wood, splattered with tallow and set ablaze in ghastly funeral pyres.

Houston gently held Susanna’s hand as she recounted the horrific scenes she had witnessed at the old mission. Each utterance by the shell-shocked widow brought grim details regarding the fate of the courageous few who had defended the Alamo’s walls. What of former U.S. congressman and living legend David Crockett? Dead. Famed knife fighter James Bowie? Dead. The defiant, patriotic Travis? Shot in the head as he’d tried to rally his men on the north wall.

“Great God, Sue, the Mexicans are inside our walls!” Susanna recalled hearing her late husband, Almeron, yell as he burst into her room within the Alamo church. “All is lost! If they spare you, save my child.”

At the retelling, widow Dickinson recalled four decades later, Houston “wept like a child.”

News of the massacre spread like a prairie fire, delivering yet another cruel blow to dozens of families in nearby Gonzales. Thirty-two volunteers from that town and the surrounding countryside had ridden to the aid of the besieged Alamo garrison. Among them were Isaac Millsaps, the husband of a blind wife and father of seven; George C. Kimble, a hatter whose wife was expecting their second child; 15-year-old William King, who had begged to ride in his father’s place; and 16-year-old Galba Fuqua, last seen by Susanna as he tried to relay a final message while propping up his bloody, shattered jaw. All were dead.

Grief hung thick in the air.

“Many of the citizens of Gonzales perished in this wholesale slaughter of Texans, and I remember most distinctly the shrieks of despair with which the soldiers’ wives received the news of the death of their husbands,” recalled John Jenkins, a 13-year-old combatant whose stepfather had died defending the Alamo. “There was not a soul left among the citizens of Gonzales who had not lost a father, husband, brother or son,” echoed Private John Milton Swisher. “The terrible massacre had, for a time, struck terror to every heart.”

In that fateful hour the immediate relatives of Alamo defenders—whether a parent, a heartbroken widow or a child—shouldered the burden of a survivor. But for generations to come the families of those slain would experience aftershocks. Their collective story of sacrifice and survival speaks to a courage approaching that of their loved ones who gave all in defense of the nascent Republic of Texas.

Frances Sutherland, the mother of 17-year-old Alamo defender William DePriest Sutherland, expressed her despair in a June 5, 1836, letter to her sister in Tennessee. She wrote in part:

I received your kind letter of some time in March, but never has it been my power to answer it till now, and now what must I say (O, God, support me). Yes, sister, I must say it to you, I have lost my William. O, yes, he is gone. My poor boy is gone, gone from me. The sixth day of March in the morning he was slain in the Alamo in San Antonio. Then his poor body committed to the flames.

‘My poor boy is gone, gone from me. The sixth day of March in the morning he was slain in the Alamo in San Antonio. Then his poor body committed to the flames’

It also fell to Benjamin Briggs Goodrich, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, to deliver news of a slain relative—brother John—to relatives in the United States. The brothers had immigrated to the Mexican province of Texas two years earlier. “The blood of a Goodrich has already crimsoned the soil of Texas, and another victim shall be added to the list, or I see Texas free and independent,” Benjamin defiantly stated in his March 15 missive.

Prudence Kimble’s husband, George, was among those Gonzales volunteers killed at the Alamo. But the widow Kimble had no time for letters in the aftermath of the siege. Reports of the massacre and subsequent approach of Santa Anna’s Mexican forces prompted Texians to evacuate eastward en masse—an exodus known as the Runaway Scrape. Determined to save her toddler, Charles, and unborn child, Prudence joined the exodus.

In a story handed down for generations, Prudence later recalled the last time she saw her husband. As she washed clothes beside a creek near their home, with Charles playing at her feet, George had strolled up. Locking eyes with Prudence, he’d spoken of the Mexican army’s presence in San Antonio and said he was joining a volunteer force to aid the besieged men at the Alamo.

“Prudence,” George had added firmly, “I probably won’t return.”

Three months later, while fleeing eastward by wagon on the Texas prairie, Prudence had given birth to twin girls—Jane and Amanda. Prudence and her three children eventually returned to their ravaged homestead. Mexican troops had torched the buildings and slaughtered the livestock. Only a lone hen with a shattered leg and a brood of chicks remained on what was left of the charred porch.

Survival came in numerous forms for the grieving families.

Mary Millsaps, the widow of defender Isaac Millsaps, faced arguably the toughest challenges, given her blindness and seven children in tow. She had scarcely begun to deal with her grief when Houston and troops fled Gonzales, inadvertently leaving behind the helpless mother and her children. On March 23, while camped at Beason’s Ferry on the Colorado River, Houston wrote of having to “send one guard 30 miles for a poor blind woman…whose husband was killed in the Alamo.”

The rider found the widow and her children hiding in brush near their home along the banks of the Lavaca River. Two years later Mary described her desperate circumstances in a plea to Texas officials for financial assistance. “My self blind and seven small children were not allowed one hour to prepare and no means of transportation,” she recalled. “We left all behind, were thrown upon the world helpless and destitute in this situation.”

In November 1838 the Texas Congress granted Mary $100 and an annual pension of $200 for the next 10 years. But the family later lost the 4,605 acres granted them for Isaac’s military service when they failed to pay property taxes amounting to $143.21. Officials sold the land at a public auction March 3, 1840, recouping $115.

Mary died in Galveston on June 8, 1842. Records show that on her death the republic awarded her surviving children the balance of their mother’s pension—$800.

Emotional scars cut deep among the Alamo defenders’ survivors, regardless of financial compensation or land. Mary Greer, daughter of Micajah Autry, never forgot the moment she received news of her father’s death. She and a playmate were gathering “snowy white dogwood blossoms” on a relative’s Jackson, Tenn., property one April morning when a voice shattered the serenity. “You must come to the house,” the messenger flatly stated. “Your father has been killed, and your mother half dead with the news.” Breathlessly, Mary ran to her mother, to be “greeted with choking sobs as she tried to tell me the tragic news.”

Her father had chronicled his journey to the Alamo in a handful of letters home. In a postscript to a Jan. 13, 1836, update from Nacogdoches, Texas, Micajah had proudly noted, “Col. Crockett has just joined our company.” Mary found comfort and pride in the fact her father served with the “celebrated Tennessee orator, Davy Crockett,” romantically writing in her reminisces how they “fell near each other in the sublime holocaust of the Alamo.”

Over time such heroic deeds and remembrances themselves stood as monuments for the grieving families.

Mary Ann (née Kent) Morriss was 8 years old when she watched her father, Andrew Jackson Kent, ride south from the family homestead along the Guadalupe River to the aid of the Alamo. In a 1916 interview 88-year-old Mary recalled how on the morning of the final siege she had huddled with siblings on the floor of the Kent cabin, frightened by the roar of cannons echoing across the prairie. Realizing the blasts were emanating from San Antonio, some 70 miles away, she feared for her father’s life. The haunting last words Mary heard her father speak as he mounted his horse were, “This time we may see blood.”

William T. Malone’s mother and father spent the remainder of their days tormented by their last memories of him. William, a strapping lad of 18, loved to socialize, gamble and drink, much to the displeasure of his strictly religious father, Thomas. One night late in 1835 the wayward son again indulged in spirits to the point of drunkenness. Rather than face the wrath of his father, William ran away from home in Athens, Ala., and made his way to New Orleans.

A regretful Thomas Malone trailed his son to New Orleans in hopes of returning him home to his distraught mother. The elder Malone arrived too late. William had already departed, having booked passage on a Texas-bound schooner. At some point on his journey the boy sent his family a letter of explanation. In the aftermath of the revolution Thomas sent an agent to Texas to inquire about the fate of his son. The agent interviewed Susanna Dickinson and Travis’ slave Joe, both of whom confirmed William’s presence and death at the Alamo.

Sorrow and anger overwhelmed Elizabeth Malone. On learning she and her husband were entitled to land in gratitude for William’s military service, the grief-stricken mother responded in wrath. “I never want to own a foot of that land,” she wrote. “I want it left for the wild beasts to roam over, because it was bought with the blood of my child.”

Elizabeth died 20 years later, in 1856, and was buried in hometown Athens. Family oral tradition relates how she carried William’s letter with her until the ink faded away.

Santa Anna’s funeral pyres ensured there would be no remains for families to view nor graves of martyrs to visit in the aftermath of the revolution, save for the ruins of the Alamo and the blood-soaked soil on which it stood

Such mementos of slain loved ones were rare among the Alamo families. After the siege Mexican soldiers had plundered the bodies of the dead Texians, while articles recovered from the battlefield were auctioned off, mainly to Mexican officers who possessed money. Santa Anna’s funeral pyres ensured there would be no remains for families to view nor graves of martyrs to visit in the aftermath of the revolution, save for the ruins of the Alamo and the blood-soaked soil on which it stood.

All of which makes the story of Mary Bullen Lewis of Philadelphia a touching footnote to an otherwise tragic saga.

Lewis, mother of defender William Irvine Lewis, wrote the Texas government in 1840 after hearing a rumor that belongings of the slain had been recovered. She was hoping to procure any possession of her son’s as a keepsake. Unfortunately, the rumor had been just that. Nothing remained.

Hoping to provide Mary some measure of comfort, sympathetic officials sent her a small monument carved of stone from the Alamo ruins. On the monument some thoughtful soul had carved the single word LEWIS.

Evidence suggests Crockett’s musket—busted at the breach—may have also made its way back to his family. During a visit to San Antonio within months of the 1836 clash a teenager named James Wilson Nichols wrote in his journal of a firearm reportedly in the hands of a local Mexican. “The naked barrel weighed 18 pounds with a plate of silver let into the barrel just behind the hind sight with the name Davy Crockette ingraved on it and another plate near the bretch with Drue Lane, maker, ingraved on it,” wrote the spelling-challenged Nichols. “Thare was a young man with us, claimed to be a son of Davy Crockett’s, baught the gun and carried it off home.”

In January 1849 a New Orleans Christian Advocate editor visited the nearby home of John Wesley Crockett, the eldest of frontiersman Crockett’s six children from two marriages. “Attached to the watch chain of the son, we often remarked a treasure,” the editor recalled. “It was a seal cut from the flint of the old hero’s Alamo musket.”

Regardless of stature, the Alamo bloodline cherished the proud legacy of sacrifice left by husbands, fathers and sons in the name of Texas liberty

Regardless of stature, the Alamo bloodline cherished the proud legacy of sacrifice left by husbands, fathers and sons in the name of Texas liberty. In an emotional July 22, 1857, speech delivered on the floor of the Texas Senate and advocating for the purchase of an Alamo monument, state Senator Henry Eustace McCulloch reminded fellow Texans of that legacy.

McCulloch harked back to the fall of 1842 when French-born Mexican General Adrián Woll mounted an expedition north of the border, invading San Antonio with some 1,400 soldiers. McCulloch, then a lieutenant of volunteers, was sent by his captain to recruit men willing to defend Texas once again. He soon arrived at the home of John and Parmelia King, on the Guadalupe outside Gonzales. The couple had lost their 15-year-old son, William, in defense of the Alamo. This time around William’s brother, John Jr., expressed an eagerness to join McCulloch’s volunteer company. “But we lost William at the Alamo,” the elder King said, turning to Parmelia. “Can we see John go, too?” Locking eyes with her tearful husband, Parmelia replied in a firm, calm voice. “’Tis true that William died at the Alamo, and we have no son to spare, but we had better lose them than our country.”

McCulloch related to his fellow senators how John Jr. went on to fight “side by side with the descendants of the heroes of the Alamo” until victory was secured. “Such, sir,” the senator concluded, “are specimens of the widows and descendants of the men whose names are inscribed upon that monument.” WW

This article was originally published in the February 2020 issue of Wild West. Ron J. Jackson Jr. is the award-winning author of Alamo Legacy and Joe, the Slave Who Became an Alamo Legend (co-authored by Lee Spencer White). For further reading he also recommends The Alamo Reader, edited by Todd Hansen; Alamo Defenders, by Bill Groneman; and A Time to Stand, by Walter Lord.