Despite Al Williams’ impressive list of aviation accomplishments, the racing, test and aerobatic pilot’s orange-painted airplanes are better known today than he is.

Lindbergh, Earhart, Doolittle, Rickenbacker, Roscoe Turner, Wiley Post, Bernt Balchen, Harold Gatty, Paul Mantz…the dean’s list of 1920s and ’30s pilots goes on, but rarely will you find Alford J. Williams Jr. on it. A Wikipedia search for “list of pilots” turns up almost 200, from Bert Acosta to Bernard Ziegler, but still no Al Williams. He may be the only aviator whose airplanes are more famous than he is. They were all called Gulfhawks and painted pumpkin orange; two of them are in the National Air and Space Museum.

Yet Williams was one of the most multitalented pilots ever to stir a stick. He had been a pitcher with the New York Giants’ farm team. A lawyer with a degree from Georgetown University and a license to practice in New York. A writer who tapped out on his portable Underwood millions of words for a nationally syndicated weekly newspaper column as well as several bestselling books. An executive of one of the world’s largest oil companies. A near concert-quality pianist who also played the guitar and accordion. A boxer who some said could have made a living in the ring.

Oh, and also a raceplane pilot who won the Pulitzer Trophy and competed for the Schneider Trophy. Holder of several world speed records. Chief test pilot of the U.S. Navy and a Marine Corps aviator as well. One of the country’s finest aerobatic and airshow pilots. An important figure in the development of dive bombing. And the force behind the design and construction of two ambitious Schneider Trophy racers, though neither ever made it to the starting line.

Williams started his aviation training in 1918 and became a naval reserve ensign and aviator. Within six months, he was made a test pilot. Obviously graced with an iron stomach and fearlessness, Williams soon became the Navy’s inverted-flight expert. He developed inverted-spin recovery techniques, assessed various inverted and vertical maneuvers for their potential use in combat and sometimes is claimed to have been the first person to fly an outside loop. (The credit for that actually goes to Jimmy Doolittle.) When Williams became an airshow pilot, one of his most impressive maneuvers was an inverted falling leaf into a half-roll to a landing at the last moment.

His greatest talent as a test pilot was that, like a good racecar driver, he could quantify a machine’s faults rather than simply say “it vibrates” or “feels squirrely.” If his assessment needed graphs or mathematical calculations, they handed him a pencil and paper.

Williams was the first serious advocate of what today is called unusual-attitude training. He believed that every pilot should be taught how to recover from every flight condition that diverged from straight-and-level. He also became a fan of parachutes, though he rarely used one during a career that included two major crashes. In the mid-1920s, he led the drive to ensure that all future Navy aircraft were designed with pilot and aircrew seats that accommodated parachutes.

The premier air competition of the early 1920s was the Pulitzer Trophy Race, the Indy 500 for airplanes. The U.S. Army Air Service won the trophy in 1920, the first year it was held. In the 1922 race, the Navy’s Al Williams could do no better than fourth. The Navy reacted like Annapolis when Army stole their goat, and Bureau of Aeronautics head Admiral William Moffett ordered his boys to take the 1923 trophy. The Navy did exactly that, filling the top four spots, with Williams in the lead.

His speed, 243.67 mph after four laps around the 31.1-mile course in a Curtiss R2C-1 biplane, was faster than the existing world speed record, so the Navy decided Williams and his friendly rival Lieutenant Harold Brow should make an official attempt at that record. In November 1923, Williams and Brow went at it over a 3-kilometer straightaway at New York’s Mitchel Field, trading top speeds back and forth. Again Williams came out on top, with a world record 266.59 mph. His reputation was made: fastest man on the planet.

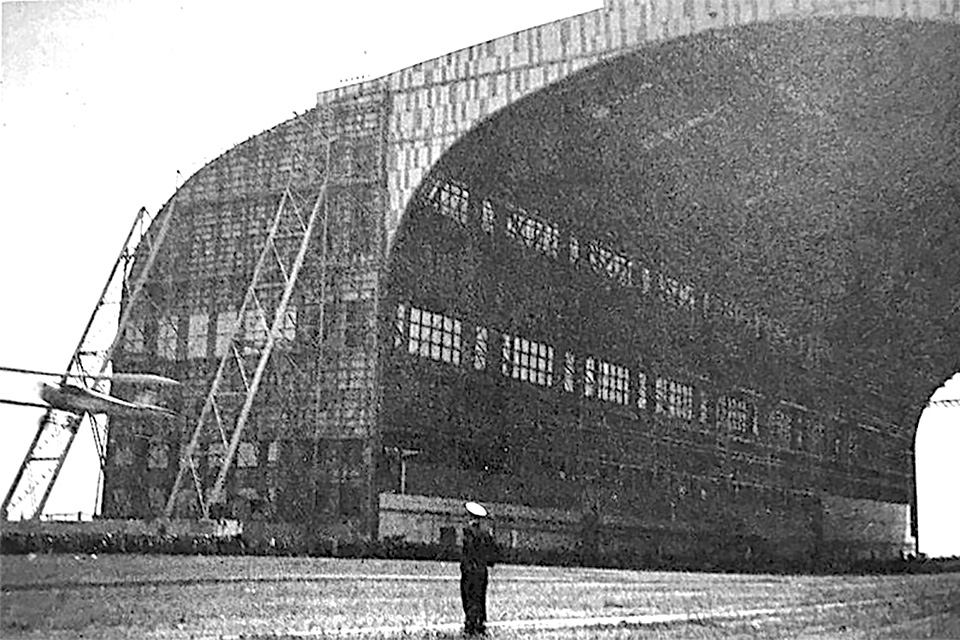

Williams now found himself with an influential patron in Admiral Moffett, one of the most powerful officers in the Navy. In fact, he became Moffett’s personal pilot. (Moffett, though the most air-minded admiral in the Navy, wasn’t himself a pilot.) The relationship was strong enough that in May 1924 Williams performed a silly stunt during an airshow at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, the Navy’s big lighter-than-air base, and got away with it: He flew through the airship Shenandoah’s huge hangar in a Vought VE-7 biplane. It took him two tries to get lined up properly, but the crowd loved it and the Navy looked the other way.

Utterly intent on furthering the cause of high-speed flight, Williams refused to stand sea duty, which was required of every Navy line officer. Though the Navy admitted that he was an outstanding air racer and aerobatic pilot, his proficiency in tactics and gunnery was deemed “far below the standard required of line officers in Naval aviation.” Nor did he know anything of carrier or scout-catapult operations.

Moffett, however, was a huge Schneider Trophy fan, and that seaplane competition was meant to be Williams’ next act on the world stage. The Navy had won the trophy in 1923, and Williams joined the combined Army-Navy race team in 1925. (There was no 1924 race.) But he didn’t make it through the preliminary trials, and Army pilot Jimmy Doolittle won the race.

Williams wasn’t selected for the 1926 team, which must have vexed him, since the Schneider that year was run right on his doorstep, off the big naval base at Norfolk, Va. Italian racers won first and third; Americans finished second and fourth.

Realizing that the Curtiss R3C raceplanes and their modified Curtiss Conqueror V-12 engines were reaching the end of their development potential, Williams set out to build his own private-entry raceplane for the 1927 Schneider: the Kirkham-Williams Racer. It would be powered by a 24-cylinder Packard engine partially funded by the Navy. The X-2775 was essentially two 600-hp Packard V-12s with a common crankcase and crankshaft between them. Since each V-12 had a 60-degree angle between its cylinder banks, this created a relatively slim, tightly cowled X engine. Output was intended to be 1,200 hp, making it America’s most powerful aircraft engine.

The Kirkham-Williams airframe, however, was not so advanced. Patterned after the Curtisses he’d been racing, it was a biplane at a time when the Italians and British were showing that monoplanes were the path to the future. Williams also chose to cover both the upper and lower surfaces of its wings with 12,000 feet of brass tubing through which engine coolant flowed, creating an enormous surface radiator. Unfortunately, the tubing decreased lift, doubled the drag of the wings and slowed the airplane down by 20 mph, according to testing later done by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

The Kirkham-Williams did fly, but the 290 mph that the floatplane was barely capable of simply wasn’t Schneider-competitive. Williams canceled his participation in the race, saying the airplane was nose-heavy and its floats vibrated. The Navy, becoming increasingly disenchanted with the concept of raceplanes as fighter precursors, didn’t even send a team to the ’27 Schneider Trophy races.

Why not put the Kirkham-Williams on wheels, then, and try for a world speed record? In November 1927, Williams did exactly that. He was able to make a single run, at an unofficially world-beating 322.42 mph, aided by a 40 mph tailwind. It was the Kirkham-Williams’ last flight.

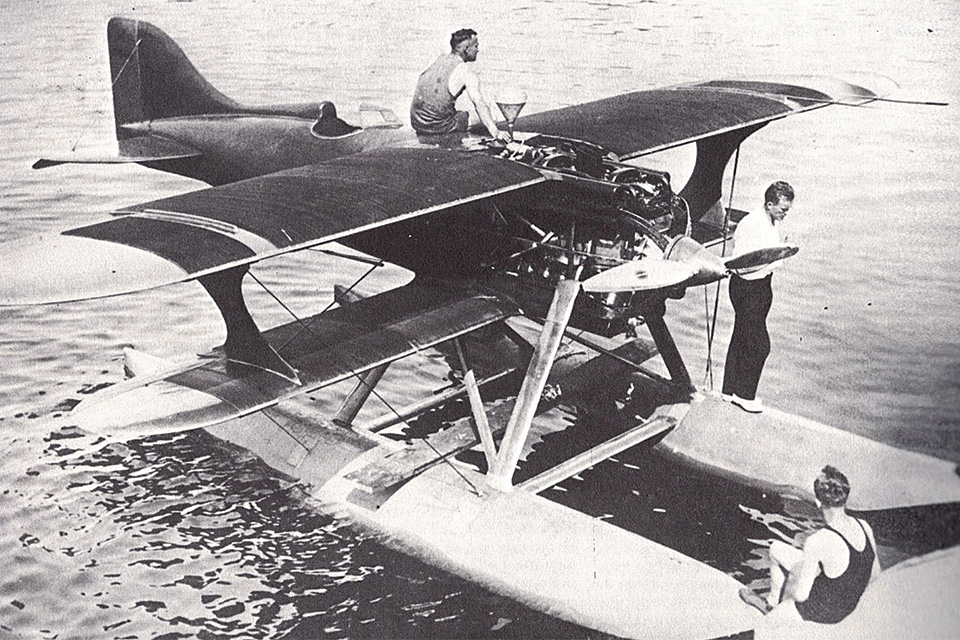

But Williams wasn’t ready to give up. He and his backers, which still included the Navy, created the 1929 Williams Mercury floatplane. Outwardly it looked like a monoplane version of the Kirkham-Williams, but it was actually an all-new airframe, though still powered by the Packard X-2775. The wings were now covered by flush surface radiators, not tubing, and the engine had a reduction gearbox that turned the propeller at two-thirds crankshaft speed for better efficiency. During the Kirkham-Williams’ development, the X-2775 had also gained a supercharger that, although heavy and inefficient, increased output to 1,400 hp.

The enormous torque of the huge 24-cylinder Packard buried the airplane’s left float and left wingtip during takeoff runs. The resultant spume bent prop blades. In fact, photos make it plain that the Williams Mercury was throwing up a wall of water, not just spray. The solution would have been to make a careful, partial-power takeoff run until the ailerons and rudder became effective, but by the time Williams figured this out, he had mangled several props.

The Williams Mercury never really flew, outside of one Spruce Gooseish 300-foot run in ground effect. The Navy rescinded its support and ordered Williams to sea duty, though he wanted another year on the beach to fix his racer’s problems. No dice, the Navy said, pack your seabag.

In a classic you-can’t-fire-me-I-quit move, Lieutenant Alford Williams Jr. resigned from the Navy in March 1930, though he soon joined the Marine Corps Reserve. He quickly became a popular airshow and aerobatic-display pilot, having bought a Curtiss Hawk 1A demonstrator originally built by Curtiss to showcase the fighter for potential foreign clients. Williams’ airplane was based on a Navy F6C-4.

With a steel-tube, wire-braced, overengineered fuselage and many-ribbed wings, the Hawk was “hell for stout,” in the words of film stunt pilot Frank Tallman, who during the 1960s restored and flew the original Williams Hawk. Tallman had found the decrepit Curtiss parked on the fifth floor of a Manhattan building that housed an aviation trade school. In his book Flying the Old Planes, Tallman also noted that the Hawk was named after a category of birds famed for their vertical-dive speed, and Williams would demonstrate that no power dive could break a Curtiss Hawk.

Williams did soon break it, however, when in October 1931 the Hawk’s engine failed during an airshow inverted falling-leaf maneuver. He managed to pancake the airplane into a parking lot, but it needed major repairs and a new engine.

This led to Williams’ involvement with an aviator as oddly multitalented as he was: Roger Wolfe Kahn, an aviation enthusiast who lent Williams his Vought O2U Corsair biplane so that Williams could continue to fly airshows while his Hawk was repaired. Kahn was a jazz musician of considerable note, a Gatsbyesque playboy and an occasional film actor whose exploits had put him on the cover of Time magazine in September 1927. Kahn’s and Williams’ paths would soon cross again, when Kahn foreswore his musical career and became, of all things, a test pilot for Grumman and ultimately manager of its technical services and sales division.

In 1933 Al Williams had been suggested as assistant secretary of war for aeronautics under new president Franklin D. Roosevelt, and he had substantial support for that position from both the military and aviation communities. Instead, he took a job as sales manager for the brand-new aviation products division of the Gulf Oil Corporation. He brought his airplane with him, and Williams’ Hawk became Gulfhawk, resplendent in a vivid orange paint job with a white sunburst atop the upper wing (so airshow crowds could tell when the airplane was inverted).

Williams represented Gulf Oil in a variety of ways, particularly by encouraging private flying and by establishing an aviation youth group, the Scripps-Howard Junior Aviators. The club ultimately had well over 400,000 teenage subscribers to his weekly aviation newspaper columns, modeling contests and radio talks. Many of those kids went on to fly in World War II.

Despite his dash through Shenandoah’s hangar, Williams despised “stunters,” his label for pilots who attempted record flights for their own glory and profit. One particular focus of his ire was Amelia Earhart, whose Lockheed Electra, he wrote in one of his Scripps-Howard newspaper columns, constituted “the latest and most distressing racket that has been given to a trusting and enthusiastic pilot. There’s nothing in that ‘Flying Laboratory’ beyond duplicates of the controls and apparatus to be found on board every major airline transport.”

Williams’ Gulfhawk became the source of an oft-cited but false claim: that he “invented” dive bombing. It’s clear that he used the Hawk to demonstrate steep dives and mock bomb drops at airshows, but the principle of dive bombing was understood and tried by the British in World War I: Pointing an airplane and its bomb at a target was more accurate than cruising over it in level flight and guesstimating when to release. The U.S. Marine Corps flew dive-bombing missions with de Havilland DH-4s during the Haitian and Nicaraguan campaigns in the 1920s, and it was not Williams but Navy Lt. Cmdr. Frank Wagner who flew the first near-vertical power dive in a Curtiss Hawk, in October 1926.

Williams, however, had befriended the German World War I ace and aerobatic pilot Ernst Udet, whom he brought to the U.S. in 1931 to represent Germany at the National Air Races, in Cleveland. There the German ace first witnessed Williams’ dive-bombing display. Hugely impressed by the Curtiss Hawk, Udet acquired two for the infant Luftwaffe and used them to experiment with the tactics that ultimately produced the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, the world’s most notorious dive bomber.

The Hawk was a 1920s design, and the small world of oil company demo pilots was a competitive one. Roscoe Turner flew a Wedell-Williams raceplane for the Gilmore Oil Company, Jimmy Doolittle of Gee Bee fame was the manager of Shell Oil’s aviation department, Frank Hawks and his Northrop Gamma Sky Chief represented Texaco, Wiley Post’s Lockheed Vega Winnie Mae was sponsored by Phillips Petroleum and other famous airplanes sported oil company logos. Williams needed something splashier than a post–World War I airplane.

He found it in Grumman’s state-of-the-art (at least by U.S. standards) F3F fighter, a barrel-bodied biplane with a big radial engine and hand-cranked retractable gear. Painted Gulf Oil orange, blue and white and with short F2F wings for greater maneuverability, it became the G-22 Gulfhawk II, the best-known of Williams’ airplanes.

Williams flew the F3F in the service of Gulf Oil from 1936 until 1948. The big biplane was used to test Gulf high-octane fuel and mil-spec lubricants, and Williams often flew Gulfhawk II while wearing a throat microphone, a device he’d refined (though not, as is often claimed, invented; that honor goes to Wiley Post). The throat mike picked up voice comm from small microphones strapped around a pilot’s neck over the vocal cords. It allowed a fighter pilot to maneuver and talk with one hand on the stick and the other on the throttle.

The only other pilot ever to fly Gulfhawk II was Udet, while the airplane was in Germany during a European tour in 1938. Williams badly wanted to fly a Messerschmitt Bf-109, and that was the quid pro quo for allowing his German friend into the Grumman’s cockpit. Williams was the first American to pilot a Bf-109, and he came away from the experience convinced that it was the best airplane he’d ever flown. Like Charles Lindbergh, who flew a 109 soon after him, Williams returned to the U.S. to warn the War Department not to underestimate the new Luftwaffe.

Williams had always advocated for a strong military air arm, something that made him no friends among the Navy’s battleship admirals; in a sense he was the Navy version of Billy Mitchell—foresighted and outspoken. He also said that such an air arm should be independent, not a subsidiary of the Army or Navy. Unfortunately, he was a decade too early. The Marine Corps, in fact, forced his resignation as a major in 1940 for what they considered to be his extreme public statements.

Williams went on to use Gulfhawk II to demonstrate aerobatics and precision flying to aviation cadets during World War II. The F3F was an antique by war’s end, so Gulf replaced it with the G-58A Gulfhawk IV, a civilianized Grumman F8F Bearcat identical to one his pal Roger Wolfe Kahn was flying on his sales calls. (Gulfhawk III was a two-seat version of Williams’ F3F that Gulf used for PR rides and utility transportation. There was also a Gulfhawk Junior, a Stinson Voyager reserved for Williams’ personal use, and five unnamed Gulf Stinson Reliants.)

Gulfhawk IV lived a brief life from August 1947 until January 1949, when the colorful airplane died in a fiery landing catastrophe at New Bern, N.C. Williams was returning from a Florida airshow when bad weather ahead caused him to opt for a precautionary stopover. Many reports suggest that the left landing-gear leg folded, though Grumman test pilot Corky Meyer, who had originally checked Williams out in the big fighter, frankly wrote that he “failed to extend his landing gear.” Whatever the case, the Grumman crushed its external belly tank, which was full of avgas. Williams escaped in time, but the inevitable fire consumed the airplane.

Years later, warbird collector Elmer Ward bought Gulfhawk’s paperwork and built a replica from Bearcat components, which he painted in Gulf colors and registered with Williams’ original tail number, NL3025. It too crashed, after an engine failure at the 1993 Oshkosh EAA airshow, within months after completion of the rebuild.

Al Williams retired from Gulf in 1951. He died of cancer in 1958 at age 62 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

For further reading, contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends Williams’ 1940 book Airpower and Al Williams: The Fleet’s First Frequent Flyer, by Dr. Raymond A. Wiley.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!