Gangster Al Capone is infamous for the years in which he and his mob virtually ruled Chicago. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the efforts of Elliot Ness and the “Untouchables” to bring him down—these are widely known elements of the Capone story.

Gangster Al Capone is infamous for the years in which he and his mob virtually ruled Chicago. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the efforts of Elliot Ness and the “Untouchables” to bring him down—these are widely known elements of the Capone story.

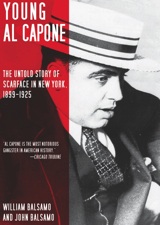

But in their new book—Young Al Capone: The Untold Story of Scarface in New York, 1899–1925, from Skyhorse Publishing—authors William and John Balsamo explore the lesser-known details of the murderous gangster’s early life, his formative years and criminal career in New York City, where he was born to immigrant parents in 1899. It is a book they’ve been researching for decades, and it promises to reveal previously unknown information on “Scarface” Al—in part because, along the way, some surviving intimates of Capone opened up to the Balsamos and shared memories they’d previously remained silent about.

Recently, William and John Balsamo agreed to an interview with HistoryNet.com.

HistoryNet.com: There have been many infamous gang leaders. What is it about Al Capone that seems to make people more fascinated with his story than with that of, say, “Lucky” Luciano or Dutch Schultz?

William Balsamo: I think the reason people are fascinated is that nickname, “Scarface,” which he really hated. In the underworld he was generally known as Al Brown. I personally believe Alphonse Capone is the most celebrated gangster in the world, not just in America.

He was sensational with numbers. He possessed great organizing abilities. He was good with the people who worked under him. “Snorky”— which meant “elegant dresser,” a moniker he loved though only his intimates were permitted to call him that—was not a prejudiced man. If you were Irish, Jewish, black—or pink, for that matter—he didn’t care. If you made money for his Cosa Nostra Chicago crime family, you were in.

He was born in the right era, at the right time. Scarface Al came along at the dawn of Prohibition, thanks to William “Wild Bill” Lovett and Richard “Peg Leg” Lonergan, leaders of Brooklyn’s deadly White Hand Gang. Capone fled them and went to Chicago, a rich, booming metropolis. The rest is history.

HN: In the course of your research, you got a number of people who knew Capone to talk with you, though they hadn’t opened up to previous researchers,. How did you manage to do that?

John Balsamo: Our “hook” as far as gaining the confidence and valuable information from those who had intimate dealings with Capone was the fact that we are related by blood to a man who is widely recognized as the first Godfather in Brooklyn, New York, Batista Balsamo. After realizing that most Capone historians concentrated on the subject’s Chicago days, we figured the tape recordings and written testimonies we acquired of Capone’s youth through the years should remain in limbo until the time we completed the life of “Young Al Capone.”

John Balsamo: Our “hook” as far as gaining the confidence and valuable information from those who had intimate dealings with Capone was the fact that we are related by blood to a man who is widely recognized as the first Godfather in Brooklyn, New York, Batista Balsamo. After realizing that most Capone historians concentrated on the subject’s Chicago days, we figured the tape recordings and written testimonies we acquired of Capone’s youth through the years should remain in limbo until the time we completed the life of “Young Al Capone.”

We were longshoremen for many years and got to know Gido Bianco, who grew up with Capone. They were both kicked out of school for fighting in sixth grade and never went back. Bianco would sit in a bar and tell us stories because he knew our great-uncle.

HN: Was there anything you learned in your research that particularly surprised you?

John: We were both surprised to learn how a man who was much smaller than Capone, Frank Galluccio (who the Balsamos say was just five-feet, two-inches tall), could get the better of Al in a rumble. Trying to cut Capone’s jugular, Galluccio instead immortalized his adversary with the nickname, “Scarface.”

HN: What elements in Capone’s early life contributed to his rise to such a pinnacle of success in the world of gangsters?

William: Capone’s firm belief that it is easier to get what you want from people with a kind word and a gun than with just a kind word—his point of view that might makes right. Capone learned a very valuable lesson from underworld big wig Frankie “Yale” Ioele: sometimes, especially when the atmosphere around you gets really hot, a person has to retreat, to into hiding so to speak, as was demonstrated in the Wild Bill Lovett and Peg Leg Lonergan affair.

HN: What was his first known incursion into crime?

John: We learned that at just 11 years old, Capone went down the slope to busy Columbia Street in downtown Brooklyn, where he was introduced to the world of “accamura” (extortion). He dubbed his little band of marauders the “South Brooklyn Rippers,” after London’s Jack the Ripper who had surgically dismembered six prostitutes in the Whitechapel murders. After failing to shake down an intended victim, a shoeshine boy, the gang vowed to try again. Thus began Capone’s life of crime.

John: We learned that at just 11 years old, Capone went down the slope to busy Columbia Street in downtown Brooklyn, where he was introduced to the world of “accamura” (extortion). He dubbed his little band of marauders the “South Brooklyn Rippers,” after London’s Jack the Ripper who had surgically dismembered six prostitutes in the Whitechapel murders. After failing to shake down an intended victim, a shoeshine boy, the gang vowed to try again. Thus began Capone’s life of crime.

HN: Legend has it that Capone got the scar that gave him his nickname “Scarface” while he was working as a bartender and bouncer at gangster Frankie Yale’s Harvard Bar. Is that story accurate as it is generally told?

William: Ninety percent of the story of how Capone received his scar is true except for a few minor details, which we present in the book. I heard the precise facts from Frank Galluccio himself, the man who created Scarface.

In the early fall of 1959, Gallucio sort of tested me with several questions, pretending that he forgot the details. He asked me, “What did they call Baptiso Balsamo? Do you recall?” I replied, “The Mayor of Union Street.”

“That’s it, that’s it,” he smiled. “Tell me, Bill, Batista’s oldest son—I knew him, you know—what was his name?” My answer of “Vito Balsamo” gave him a thrill. Galluccio sprang from his chair and patted my cheek. Only after I satisfied his curiosity did he sit back on his chair and tell me the entire narrative. He was a great storyteller.

Unfortunately Frank Galluccio passed away at age 62 of a heart attack on September 24, 1960—exactly one year after the interview he granted me. He was waked at the Romanelli Funeral Home in Brooklyn and buried in St. John’s cemetery on September 28, 1960.

HN: How do the street gangs of young Capone’s neighborhood compare to today’s “youth gangs?”

William: The street gangs of Capone’s era had nothing; that was also true of the teenage gangs of the early 1950s, the era when I grew up. In both eras, they came from poor families; there is no difference when you compare the South Brooklyn Rippers of Capone’s early teenage years and the Kane Street Midgets of the early 1950s.

The ruffians of those days fought pitched battles with garrison belts, landing well-aimed blows to a foe’s skull area with two-inch square brass buckles. A table leg or a lead pipe was effective in teenage gang warfare, too. Occasionally a homemade .22-caliber zip gun was shoved under the belt of a youthful delinquent as he charged into battle.

The young hoodlums of today fight with pistols or knives. Today’s gang members participate in drive-by shootings and cold-blooded murder.

The bad boys of Capone’s time would break an enemy’s head with a table leg. In the 1950s, we made our own toys, crude wooden pistols that shot half-inch square pieces of linoleum, using rubber bands to propel the ammunition. Most gang members of Capone’s youth and of the 1950s drifted away at age 18 and eventually got married and raised families. So much for those old days.