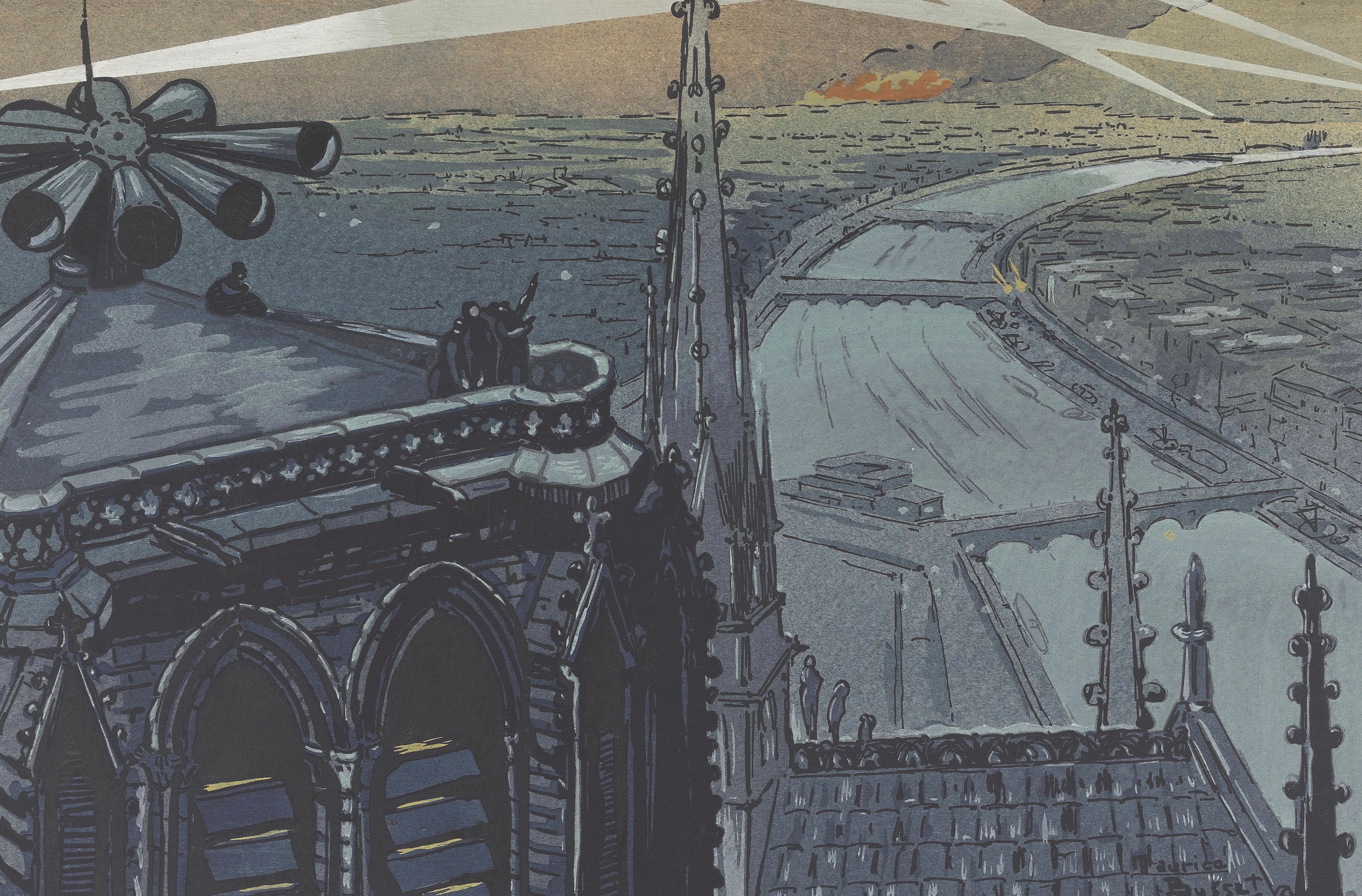

Maurice Busset used an age-old medium—wood-block prints—to depict Germany’s terrifying air raids on Paris during World War I.

THE NEW INCARNATIONS OF WARFARE USHERED IN DURING WORLD WAR I—primitive tanks, frightening poison gases, and, above all, terrifying aerial bombardment and combat—demanded new approaches from artists who wanted to depict the increasing mechanized realities of war. The traditional conventions of depicting battles and other military engagements no longer sufficed.

French artist Maurice Busset (1879–1936) turned to an age-old medium—wood-block prints—to portray the 1918 German air raids on Paris in a portfolio he titled Paris Bombardé (Paris Bombarded).

The bombardment of Paris was part of Germany’s Spring Offensive (also known as the Ludendorff Offensive)—a massive attack on the Western Front that brought German forces within 75 miles of Paris. The Germans had bombed Paris before, in 1915 and 1916. But the attacks of 1918 were on a larger, more lethal scale. Beginning January 30, Gotha bombers, which were faster and easier to maneuver than the Zeppelins that had carried out previous air raids, attacked Paris by night. In March, Germany’s colossal “Paris Guns”—cannons specially built to bombard the French capital at the unheard-of range of 75 miles—began shelling the city by day.

Over five months, the Germans flew 44 raids over Paris and dropped a total of 55,000 pounds of explosives on the city, killing 241 people and injuring hundreds more. In comparison, the attacks of 1915 and 1916 had left 34 people dead. The most shocking of the aerial attacks had come on March 29, 1918, Good Friday, when a shell hit the centuries–old Church of St.-Gervais-et-St.-Provais, causing its vaulted roof to collapse and killing 88 worshipers.

By the standards of air raids later in the 20th century, the damage the Paris bombardment caused was minimal. But if the physical damage was slight, the psychological impact was not. The use of air raids and heavy artillery against the city marked a significant break with previous wars. The raids were the harbinger of a new and horrifying form of warfare, in which civilians were intentionally targeted by combatants as a way of breaking the enemy’s morale.

UNLIKE MANY OF THE OTHER ARTISTS WHO RECORDED HOW MECHANIZED WARFARE affected soldiers and civilians, Busset was not a member of the artistic avant-garde. After training at the Beaux-Arts academy in Clermont-Ferrand in his native region of Auvergne, Busset studied for a short time in Paris. At first he attended classes in the studios of two leading academic painters, Jean-Gérôme Léon and Fernand Cormon, but he didn’t find the instruction as useful as he had expected. Busset was more interested in the landscape and ethnography of his native Auvergne than in the history paintings and exotic Orientalist scenes that were the preferred subjects of academic painters. He soon abandoned traditional arts training in favor of the school of decorative arts, where he studied with Charles-Paul Renoard, a well-known illustrator and painter, and learned the techniques of wood-block printing.

Financial difficulties sent Busset back to Auvergne, where he became a leading member of the regionalist art movement, whose members focused on recording scenes from the traditional rural life now threatened by the spread of industrialism. Busset exhibited widely, organized exhibitions of regionalist art, taught at the local arts academy where he had trained, and took long-distance sketching tours by bicycle.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 introduced Busset to a very different milieu than the rural life and landscapes that had inspired so much of his work so far.

Busset had performed his obligatory military service more than a decade before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife in Sarajevo would lead to the outbreak of war. Although Busset was exempted from further service when the war began, he nonetheless chose to enlist.

BUSSET’S TIME IN THE TRENCHES, HOWEVER, TURNED OUT TO BE RELATIVELY BRIEF. He fought at the Battle of Bois d’Ailly in May 1915 as a member of the 10th Infantry. In July he came down with an “infectious fever” and was sent to the convalescent hospital in Auxonne. As Busset recovered, he began to draw a new subject in his sketchbook: views of the airfield at Longvic, with a notation that he had volunteered to train as an aviation mechanic.

The rest of Busset’s military career centered on aviation. For a time he served as a mechanic with the 1st Aviation Group of Longvic. In September 1917 he became a warrant officer in the Aéronautique Militaire, then a branch of the French army. Charged with collecting information for the Archive of Military Aviation, Busset traveled to air bases throughout France.

It isn’t known how much time, if any, Busset actually spent in a plane, but the new world of aviation had clearly captured his imagination. His sketchbooks from the period demonstrate that he approached planes and aviators with the same ethnographic curiosity and attention to physical details that he had previously brought to the shepherds of Auvergne. He made accurate drawings of the hangars and different models of airplanes that the French army used: Caudron and Farman reconnaissance planes, Morane-Saulnier fighters, and Voisin bombers. He sketched portraits of French aces René Paul Fonck and Georges Guynemer and other pilots in their heavy jackets and distinctive leather helmets. He drew pictures of aerial observers climbing out of planes, clutching the fragile instruments they used to take reconnaissance photographs.

After the war, the newly founded Musée de l’Aéronautique (now the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace) hired Busset to work as a military painter. It was there, at the museum, that Busset created Paris Bombardé, a portfolio of 13 colored wood-block prints and two etchings, interleaved with pages of text that capture the sensory elements of the events depicted instead of describing the action.

Busset’s sketches of life among France’s military aviators are detailed and highly realistic. The prints in Paris Bombardé are not.

Each print is framed on the page like an illustration in a children’s book. Flat planes of exaggerated, and often improbable, colors are set off by strong black outlines. Light is used as an accent in an unrealistic nightscape. Diagonal lines of golden light from the searchlights that were an integral element of French air defenses slash through turquoise, blue, and purple night skies. Bursts of antiaircraft fire twinkle like fireworks of gold and red. The domestic lights of the city appear as small yellow patches that glow but do not illuminate. Fires rage golden against monochrome backgrounds of orange, red, or hot pink, in which buildings are distinguished from sky only by shadow and outline.

Busset depicts the raids from multiple perspectives, but all of them are at an emotional remove. His landscapes include ruined buildings but not broken bodies (historically reasonable given the low death toll of the raids). Civilians fight fires where a bomb has hit and hurry to take shelter in a Métro station, but they do not panic or run around screaming. Most of Busset’s figures face away from the viewer. A watchman stands alone on a tower. Soldiers man an antiaircraft gun. Without connection to a human face, the viewer, too, watches the sky for the first glimpse of a bomber, focuses on the target, or looks toward the safety of the Métro station.

Ultimately, the drama of the prints comes not from the action itself but from the intensity of the color with which Busset portrays the action. He transforms the terrifying potential of mechanized warfare into glorious spectacle.

After a brief period at the Musée de l’Aéronautique, Busset turned his back on military subjects and returned home to a quiet life in Auvergne. Although he is largely forgotten today, he enjoyed modest artistic and financial success. He was a popular commercial illustrator, with more than 300 works attributed to him. He continued to teach. Busset served as the curator at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Clermont-Ferrand, where he was an ardent promoter of the region’s art and artists. It’s hard to imagine a life more distant from what the preface to Paris Bombardé described as “our brutal age of steel, machine, and explosives.” MHQ

Pamela D. Toler, who writes about history and the arts, is the author of Heroines of Mercy Street: The Real Nurses of the Civil War (Little, Brown and Company, 2016) and Women Warriors: An Unexpected History (Beacon Press, 2019).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2019 issue (Vol. 32, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Artists | Air Raids over Paris

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!