The Doolittle attack generated more, and more violent, ripples than once thought.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL JIMMY DOOLITTLE at the controls of a B-25 Mitchell medium bomber, zoomed low over northern Tokyo at midday on Saturday, April 18, 1942. He could see the high-rises crowding the Japanese capital’s business district as well as the imperial palace and even the muddy moat encircling Emperor Hirohito’s home.

“Approaching target,” the airman told his bombardier.

Doolittle pulled back on the yoke, climbing to 1,200 feet. The B-25’s bomb bay doors yawned.

“All ready, Colonel,” the bombardier said.

Amid antiaircraft fire from startled gunners on the ground, Doolittle leveled off over northern Tokyo. At 1:15 p.m. the red light on his instrument panel blinked as his first bomb plummeted. The light flashed again.

Then again.

And again.

Four bombs—each packed with 128 four-pound incendiary bomblets—tumbled onto Tokyo as Doolittle dove to rooftop level and turned south, back toward the Pacific. The veteran airman had accomplished what four months earlier had seemed impossible. The United States had bombed the Japanese homeland, a feat of arms and daring aviation that would stiffen the resolve of a demoralized America.

For more than seven decades Americans have celebrated the Doolittle Raid largely for reasons that have little to do with the mission’s tactical impact. A handful of bombers, each carrying two tons of ordnance, after all, could hardly dent a war machine that dominated nearly a tenth of the globe. Rather, the focus has been on the ingenuity, grit, and heroism required to execute what amounted to a virtual suicide mission, which Vice Admiral William Halsey Jr. hailed in a personal letter to Doolittle. “I do not know of any more gallant deed in history than that performed by your squadron,” wrote Halsey, who commanded the task force that transported Doolittle and his men to Japan. “You have made history.”

But the raid did have a significant impact, some of those outcomes positive, some very dark. The American bomber squadron inflicted widespread damage in the target areas but also caused civilian deaths that included children at school. In retaliatory campaigns that went on for months, Japanese military units killed hundreds of thousands of Chinese. And in the years following the Japanese surrender, American occupation authorities sheltered a general suspected of war crimes against some of the aviators. All these facts have been illuminated only recently through declassified records and other previously untapped archival sources.

The new information in no way undermines the bravery of the first Americans to fly against Japan’s homeland. Rather it shows that after more than 70 years, one of the war’s best known and most iconic stories still has the power to reveal more about its intricacies and effectiveness.

EVEN AS CREWS were recovering American dead from Pearl Harbor’s oily waters, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was demanding that his senior military leaders take the fight to Tokyo. As Army Air Forces chief Lieutenant General Henry Arnold later wrote, “The president was insistent that we find ways and means of carrying home to Japan proper, in the form of a bombing raid, the real meaning of war.”

Thus the concept of a surprise attack on the Japanese capital was born. Within weeks, a plan emerged. An aircraft carrier protected by a 15-ship task force—including a second carrier, four cruisers, eight destroyers, and two oilers—would steam into striking distance of Tokyo. Taking off from the carrier—something never before attempted—16 B-25 medium bombers would assault Tokyo and the industrial cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, Kanagawa, Kobe, and Osaka. After spreading destruction across more than 200 miles, the airmen would fly to regions of China controlled by the Nationalists. Navy planners had the perfect vessel in mind—the USS Hornet, America’s newest flattop. The Tokyo raid would be the $32 million carrier’s first combat mission.

To oversee the Army Air Forces’ role, Arnold tapped his staff troubleshooter, Doolittle. The 45-year-old had chafed his way through World War I, forced because of his excellent flying skills to train others. “My students were going overseas and becoming heroes,” he later griped. “My job was to make more heroes.” What Doolittle lacked in combat experience, the airman with an ear-to-ear to grin—and MIT doctorate—more than made up for in intelligence and daring, character traits that would prove vital to the Tokyo raid’s success.

But where to bomb in Tokyo, and what? One Japanese in 10 lived there. The population was nearly seven million, making Japan’s capital the world’s third largest city after London and New York. In some areas population density exceeded 100,000 per square mile, with factories, homes, and stores jumbled together. Commercial workshops often doubled as private residences, even in areas classified as industrial.

As they studied maps, the colonel drilled his 79 volunteer pilots, navigators, and bombardiers on the need to hit only legitimate military targets. “Crews were repeatedly briefed to avoid any action that could possibly give the Japanese any ground to say that we had bombed or strafed indiscriminately,” he said. “Specifically, they were told to stay away from hospitals, schools, museums, and anything else that was not a military target.” But there was no guarantee. “It is quite impossible to bomb a military objective that has civilian residences near it without danger of harming the civilian residences as well,” Doolittle said. “That is a hazard of war.”

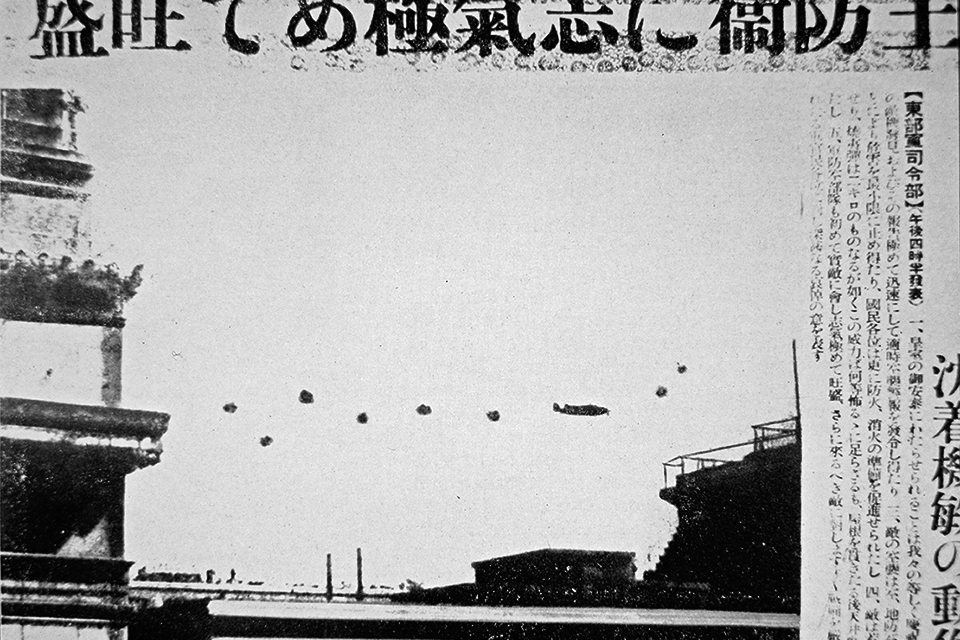

THE 16 BOMBERS ROARED OFF the Hornet’s deck on the morning of April 18, 1942. All bombed targets but one, whose pilot had to ditch his ordnance in the sea to outrun fighters. According to materials only lately brought to light, the raid obliterated 112 buildings and damaged 53, killing 87 men, women, and children. Among 151 civilians seriously injured, one was a woman shot through the face and thigh while gathering shellfish near Nagoya. At least 311 others suffered minor injuries.

In Tokyo, the raiders burned the Communication Ministry transformer station, as well as more than 50 buildings around the Asahi Electrical Manufacturing Corporation factory and 13 adjoining the National Hemp and Dressing Company. In Kanagawa Prefecture, just south of Tokyo, raiders targeted foundries, factories, and warehouses of the Japanese Steel Corporation and Showa Electric as well as the Yokosuka Naval Base. Robert Bourgeois, bombardier of the 13th plane, which attacked Yokosuka, later commented on the intensity of his preparation. “I had looked at the pictures on board the carrier so much that I knew where every shop was located at this naval base,” he recalled. “It was as if it were my own backyard.”

In Saitama Prefecture, to the north, bombardiers blasted Japan Diesel Corporation Manufacturing. At Nagoya, a massive Toho Gas Company storage tank burned completely. Bombs there also damaged a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries aircraft factory. Six wards of the army hospital went up in flames, along with a food warehouse and army arsenal.

The Japanese logged the results of the war’s first raid on their homeland in minute detail, records that largely survived the 1945 bombardment of Tokyo and the deliberate destruction of records that preceded Japan’s surrender. Pilot Edgar McElroy’s attack on the Yokosuka Naval Base ripped a 26-by-50-foot hole in submarine tender Taigei’s port side, delaying its conversion to an aircraft carrier for four months. One of pilot Harold Watson’s 500-pound demolition bombs penetrated a warehouse filled with gasoline, heavy oil, and volatile methyl chloride, only to bounce into the neighboring wooden building before exploding. Bombs left craters 10 feet deep and 30 feet across. A dud ripped through a house to bury itself in the clay beneath, forcing the military to set a 650-foot perimeter to excavate the projectile.

As Doolittle anticipated, the attack burned residences from Tokyo to Kobe. In 2003 Japanese historians Takehiko Shibata and Katsuhiro Hara revealed that pilot Travis Hoover alone destroyed 52 homes and damaged 14. One bomb blew a woman from the second floor of her house to land unhurt in the street atop a mat. In the same neighborhood 10 civilians died, some burning to death in collapsing houses. Pilots Hoover, Robert Gray, David Jones, and Richard Joyce accounted for 75 of the 87 fatalities. Jones’s attack claimed the most lives—27.

Gray strafed what he thought was a factory, complete with a rooftop air defense surveillance tower. But it was Mizumoto Primary School, where students, like many across Japan, attended half-day classes on Saturdays. After school let out at 11 a.m, many students had stayed to help clean classrooms; one died in the strafing attack. At Waseda Middle School, one of Doolittle’s incendiaries killed fourth-grader Shigeru Kojima. Children’s deaths became a rallying point. A Japanese sergeant later captured by Allied forces described the furor that erupted from the raid. “One father wrote to a leading daily telling of the killing of his child in the bombing of the primary school,” his interrogation report stated. “He deplored the dastardly act and avowed his intention of avenging the child’s death by joining the army and dying a glorious death.”

ALL 16 CREWS made it out of Japan. Low on fuel, one pilot flew northwest across the Japanese mainland to Vladivostok, Russia, where authorities interned him and his crew for 13 months. The rest flew south along the Japanese coast, rounding Kyushu before crossing the East China Sea to mainland Asia. Aircrews bailed out or crash-landed along the Chinese coast, getting help from locals and missionaries. Bent on preventing further strikes, furious Japanese leaders tried in June to extend the nation’s defensive perimeter with a grab for Midway, triggering a disastrous naval battle that cost them four carriers and shifted the balance of power in the Pacific in favor of America.

But the raiders’ choice of haven revealed coastal China as another dangerous gap in the empire’s defense. Japan already had many troops in China. Within weeks, the Imperial General Headquarters sent the main force of the Thirteenth Army and elements of the Eleventh Army and the North China Area Army—a total force that would swell to 53 infantry battalions and as many as 16 artillery battalions—to destroy the airfields the Americans had hoped to use in the provinces of Chekiang and Kiangsi. “Airfields, military installations, and important lines of communication will be totally destroyed,” the order read. The unwritten command was to make the Chinese pay dearly for their part in the empire’s humiliation.

Details of the destruction emerged from previously unpublished records on file at Chicago’s DePaul University. Father Wendelin Dunker, a priest based in the village of Ihwang, fled the Japanese advance along with other clergy, teachers, and orphans under the church’s care, hiding in the mountains. He returned to find packs of dogs feasting on the dead. “What a scene of destruction and smells met us as we entered the city!” he wrote in an unpublished memoir.

The Japanese returned to Ihwang, forcing Dunker out again. Troops torched the town. “They shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved,” Dunker wrote. “They raped any woman from the ages of 10–65.”

Ihwang’s destruction proved typical. Bishop William Charles Quinn, a California native, returned to Yukiang to find little more than rubble. “As many of the townspeople as the Japs had been able to capture had been killed,” he said. One of the worst hit was the walled city of Nancheng. Soldiers rounded up as many as 800 women, raping them day after day. Before leaving, troops looted hospitals, wrecked utilities, and torched the city. In Linchwan troops tossed families down wells. Soldiers in Sanmen sliced off noses and ears.

The Japanese were harshest on those who helped the raiders, as revealed in the diary of the Reverend Charles Meeus, who toured the devastated region afterward and interviewed survivors. In Nancheng, men had fed the Americans. The Japanese forced these Chinese to eat feces, then herded a group chest-to-back 10 deep for a “bullet contest,” to see how many bodies a slug pierced before stopping. In Ihwang, Ma Eng-lin had welcomed injured pilot Harold Watson into his home. Soldiers wrapped Ma Eng-lin in a blanket, tied him to a chair and soaked him in kerosene, then forced his wife to set her husband afire.

Canadian missionary Bill Mitchell traveled the region for the Church Committee for China Relief. Using local government data, Reverend Mitchell calculated that Japanese warplanes flew 1,131 raids against Chuchow—Doolittle’s destination—killing 10,246 people and leaving 27,456 destitute. Japanese soldiers destroyed 62,146 homes, stole 7,620 head of cattle, and burned a third of the district’s crops.

Japan saved the worst for last, unleashing secretive Unit 731, which specialized in bacteriological warfare. Spreading plague, anthrax, cholera, and typhoid by spray, fleas, and contamination, Japanese forces fouled wells, rivers, and fields. Journalist Yang Kang, reporting for newspaper Ta Kung Pao, visited the village of Peipo. “Those who returned to the village after the enemy had evacuated fell sick with no one spared,” she wrote in a September 8, 1942, article. Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, who accompanied Kang, said disease had left entire cities off limits. “We avoided staying in towns overnight, because cholera had broken out and was spreading rapidly,” he wrote. “The magistrate assured us that every inhabited house in the city was stricken with some disease.”

Japan’s approximately three-month terror campaign infuriated the Chinese military, who recognized it as a byproduct of a raid meant to boost American morale. In a cable to the U.S. government, General Chiang Kai-shek claimed the Doolittle strike cost his nation 250,000 lives. “After they had been caught unawares by the falling of American bombs on Tokyo, Japanese troops attacked the coastal areas of China, where many of the American fliers had landed. These Japanese troops slaughtered every man, woman, and child in those areas,” Chiang wrote. “Let me repeat—these Japanese troops slaughtered every man, woman, and child in those areas.”

IN THEIR SWEEP through coastal China, Japanese forces captured eight Doolittle raiders. Accused of indiscriminately killing civilians, all were tried for war crimes and sentenced to death. The Japanese executed three in Shanghai in October 1942 but commuted the others’ sentences to life in prison, in part for fear that executing all of them might jeopardize Japanese residents in the United States. Of the surviving raiders, one flyer starved to death in prison while the other four languished for 40 months in POW camps. Upon Japan’s capitulation, Allied authorities arrested four Japanese who played a role in the imprisonment and execution of the raiders. Those included the former commander of the Thirteenth Army, Shigeru Sawada, the judge and the prosecutor who tried the raiders, and the executioner.

War crimes investigators weren’t satisfied justice would be served by prosecuting only those four. Investigators likewise doggedly pursued ex-general Sadamu Shimomura, who had replaced Sawada as commander of the Thirteenth Army on the eve of the raiders’ executions. Shimomura himself was said to have signed the order to kill the Americans. As the war was ending, Shimomura was elevated to be Japan’s war minister; after the surrender, he worked closely with American authorities to demobilize the Imperial Army.

In December 1945, investigators following up on the executions of Doolittle raiders asked occupation authorities to arrest Shimomura. General Douglas MacArthur’s staff refused; the former general was too valuable an asset in managing the conquered country. The investigators persisted. If Shimomura figured in raiders’ executions, they reasoned, he should be prosecuted. On January 11, 1946, they formally requested his arrest. MacArthur’s staff again balked, this time claiming the case would be considered from an “international standpoint,” alluding to Shimomura’s importance in postwar Japan. On January 23, the investigators again sought Shimomura’s arrest, then came to Japan, arousing international news coverage.

Shimomura was arrested and interned at Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison in early February 1946. In March the other four defendants went on trial. To keep Shimomura out of court, members of MacArthur’s staff did all they could, going so far as to elicit statements from witnesses that might exonerate the former general. In the end, MacArthur’s intelligence chief, Major General Charles Willoughby, played the following-orders card. “As the final decision for the execution of the fliers had been made by Imperial General Headquarters, Tokyo, on 10 October,” Willoughby wrote in a memo, “the signature of the Commanding General Thirteenth Army on the execution order was simply a matter of formality.”

The other four defendants made the same argument, but they were tried and convicted; three were sentenced to five years hard labor and one received nine years. For Shimomura, however, the tactic worked—if only because it ran out the clock. Efforts by MacArthur’s staff on Shimomura’s behalf so delayed the legal process that there wasn’t time to prosecute him. “The War Crimes mission in China is about to close,” stated a concluding memo in September. “Further action by this Headquarters with respect to the trial of General Shimomura is no longer possible. Accordingly, this Headquarters is not disposed to take any action in the case.”

Willoughby orchestrated Shimomura’s secret release, including the stealthy elimination of his name from prison reports. A driver took him to his home on March 14, 1947, before officials sent him “to a quiet place for a few months.” The man who had allegedly inked his name to the execution order for Doolittle’s raiders never served another day in jail. Shimomura was later elected to the Japanese parliament before a 1968 traffic accident claimed his life at age 80.

Compared to 1945’s B-29 raids—when as many as 500 bombers flew nightly against Japan, leveling cities by the square mile—the Doolittle raid was a pinprick. But, as history has shown, those 16 bombers delivered a disproportionate punch—leading America to celebrate its first victory of the war, the Chinese to mourn a quarter-million dead, and the Japanese to blunder into defeat at Midway. Doolittle raider Robert Bourgeois summed up the story many years later.

“That Tokyo raid,” the old bombardier said. “That was the daddy of them all.”

Originally published in the May/June 2015 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.