In the dimly lit log cabin of the Widow Glenn, the military map was spread. Worried Union officers of the Army of the Cumberland crowded around as Major General William S. Rosecrans, their haggard commander, asked for an assessment of the situation facing his troops on the night of September 19, 1863. Sunday morning would certainly bring with it a renewal of the savage fighting that had swirled along the banks of Chickamauga Creek most of that day.

The Union army had been hard-pressed along an extended battle line, but had refused to break under the pressure of repeated assaults from General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee. The XIV Corps of Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas had borne the brunt of some of the fiercest fighting. Bone tired from his day’s work, Thomas settled back in a chair and napped. As was his practice, Rosecrans in turn asked each officer for his advice on the fight to come. Each time his name was mentioned, Thomas roused long enough to say, ‘I would strengthen the left,’ before falling back asleep.

Though Rosecrans’ army had been bloodied, its line was still unbroken, and the decision was made to renew the battle on the 20th on essentially the same ground the troops now occupied. Thomas would be reinforced and charged with holding the left, which crossed the LaFayette Road, the vital link to strategically important Chattanooga, Tenn., 10 miles to the north. Major General Alexander McCook’s XX Corps would close up on Thomas’ right, while Thomas Crittenden’s XXI Corps would be held in reserve. During the night, the ringing of axes told waiting Confederates their enemy was desperately strengthening his positions.

The Army of the Cumberland had fought bravely, and there was cause for optimism among the Union commanders. Since coming out of winter quarters, Rosecrans had brilliantly maneuvered Bragg and his army out of Tennessee and captured Chattanooga, virtually without firing a shot. In his moment of supreme success, however, Rosecrans made one error: he mistook Bragg’s orderly withdrawal for headlong retreat and rashly divided his force into three wings. As these separate forces moved blindly through mountain passes into the north Georgia countryside in pursuit of a ‘beaten’ foe, each was too distant to lend support to the others in the event of an enemy attack. With the Federal troops spread over a 40-mile-wide front in unfamiliar terrain, Bragg halted his forces at LaFayette, Ga., 25 miles south of Chattanooga.

Bragg realized the magnitude of his opportunity to deal with each wing of the Union army in detail and win a stunning victory for the Confederacy. He ordered his subordinates to launch attacks on the scattered Federal units, but they were slow–even uncooperative–in responding. The relationships between Bragg and his lieutenants had seriously deteriorated after questionable retreats from Perryville, Ky., and Murfreesboro, Tenn. Bragg’s corps and division commanders felt almost to a man that he had squandered victories by his inept handling of troops. The lack of cooperation in the higher echelons of Bragg’s army contributed greatly to the squandering of a chance for one of the most lopsided victories of the war.

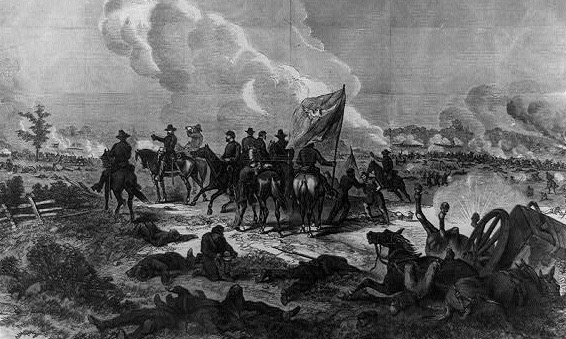

In the nick of time, and with substantial help from his enemy, Rosecrans collected his troops in the vicinity of Lee and Gordon’s Mill along the banks of a sluggish little stream the Cherokee Indians had named ‘Chickamauga’ after the savage tribe that had lived there many years earlier. Now, two great armies would prove once again that ‘River of Death’ was an accurate translation. In the vicious but indecisive fighting of September 19, both Rosecrans and Bragg committed more and more troops to a struggle which began as little more than a skirmish near one of the crude bridges that crossed the creek. Though little was accomplished the first day, the stage was set for a second day of reckoning.

The importance of the war in the West was not lost on the Confederate high command. Already three brigades of the Army of Northern Virginia, under Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood, had arrived by rail to reinforce Bragg. Lieutenant General James Longstreet, Robert E. Lee’s ‘Old Warhorse’ and second in command, was due at any time with the balance of his I Corps. These veteran troops would give Bragg an advantage few Confederate commanders would know during the war–numerically superiority. As the Virginia troops arrived, Bragg’s army swelled to 67,000 men, outnumbering the Federals by 10,000.

While Rosecrans convened his council of war at the Widow Glenn’s, Longstreet was searching for the elusive Bragg. Bragg unaccountably had failed to send a guide to meet him, and after a two-hour wait, Longstreet struck out with his staff toward the sound of gunfire.

As they groped in the darkness, Longstreet and his companions were met with the challenge. ‘Who comes there?’ ‘Friends,’ they responded quickly. When the soldier was asked to what unit he belonged, he replied with numbers for his brigade and division. Since Confederate soldiers used their commanders’ names to designate their outfits, Longstreet knew he had stumbled into a Federal picket. In a voice loud enough for the sentry to hear, the general said calmly, ‘Let us ride down a little and find a better crossing.’ The Union soldier fired, but the group made good its escape.

When Longstreet finally reached the safety of the Confederate lines, he found Bragg asleep in an ambulance. The overall commander was awakened, and the two men spent an hour discussing the plan for the following day. Bragg’s strategy would continue to be what he hoped to achieve on the 19th. He intended to turn the Union left, placing his army between Rosecrans and Chattanooga by cutting the LaFayette Road. Then, the Confederates would drive the Army of the Cumberland into the natural trap of McLemore’s Cove and destroy it, a piece at a time.

Bragg now divided his force into two wings, the left commanded by Longstreet and the right by Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, the ‘fighting bishop’ of the Confederacy. Polk would command the divisions of John C. Breckinridge, who had serves as vice president of the United States under President James Buchanan, and Patrick Cleburne, a hard-fighting Irishman. Also under Polk were the divisions of Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, States Rights Gist and St. John R. Liddell. Breckinridge and Cleburne were under the direct supervision of another lieutenant general, D.H. Hill. Longstreet was given the divisions of Evander Law and Joseph Kershaw of Hood’s corps, A.P. Stewart and William Preston of Simon Bolivar Buckner’s corps, and the divisions of Bushrod Johnson and Thomas Hindman.

Breckinridge and Cleburne were to begin the battle with a assault on Thomas at the first light. The attack was to proceed along the line, with each unit going into action following the one on its right. Bragg’s order subordinating Hill to Polk precipitated some costly confusion among Southern commanders as the time for the planned attack came and went. Somehow, Hill had been lost in the shuffle and never received the order to attack. Bragg found Polk calmly reading a newspaper and waiting for his breakfast two miles behind the lines. Polk had simply assumed that Bragg himself would inform Hill of the battle plan.

When the Confederate tide finally surged forward at 9:45 a.m., Thomas was ready with the divisions of Absalom Baird, Richard Johnson, John Palmer and John Reynolds. Breckinridge’s three brigades hit the extreme left of the Union line, two of them advancing smartly all the way to the LaFayette Road before running into reinforcements under Brig. Gen. John Beatty, whose 42nd and 88th Indiana regiments steadied the Federal line momentarily. A redoubled Rebel effort forced the 42nd back onto the 88th, and several Union regiments were obliged to shift their fire 180 degrees to meet the thrust of enemy troops in their rear. Fresh Federal soldiers appeared and finally pushed Breckinridge back.

Cleburne’s troops followed Breckinridge’s assault and suffered a similar fate. The hard-pressed Rebels pulled back 400 yards to the relative safety of a protecting hill. As he inspected the ammunition supply of his men before ordering them forward again, one of Cleburne’s ablest brigadiers, James Deshler, was killed by an exploding shell that ripped his heart from his chest. Seeking shelter in a grove of tall pines, the Confederates traded round for round but could not carry the breastworks.

Thomas’ hastily constructed breastworks had proven to be of tremendous value, but several of the Union regiments suffered casualties of 30 percent or higher. The brigades of Colonel Joseph Dodge, Brig. Gen. John H. King, Colonel Benjamin Scribner and Brig. Gen. John C. Starkweather had held the extreme left of the Union line since the day before and had been engaged for over an hour when Cleburne’s attacks gained their full fury. For all their seeming futility, the Confederate assaults against Rosecrans’ left did have one positive result. Thomas’ urgent pleas for assistance were causing Rosecrans to thin his right in order to reinforce the left through the thick, confusing tangle of forest.

At the height of the fighting on the left, one of Thomas’ aides, Captain Sanford Kellogg, was heading to Rosecrans with another of Thomas/ almost constant requests for additional troops. Kellogg noticed what appeared to be wide gap between the divisions of Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood on the right and John Reynolds on the left. In actuality, the heavily wooded area between Reynolds and Wood was occupied by Brig. Gen. John Brannan’s division. When Kellogg rode by, Brannan’s force was simply obscured by late-summer foliage.

When Kellogg informed Rosecrans of the phantom gap, the latter reacted accordingly. In his haste to avoid what might be catastrophe for his army, Rosecrans did not confirm the existence of the gap but, instead, issued what might have been the single most disastrous order of the Civil War. ‘Headquarters Department of Cumberland, September 20th–10:45 a.m.,’ the communiqué read. ‘Brigadier-General Wood, Commanding Division: The general commanding directs that you close up on Reynolds as fast as possible and support him.’

Earlier that morning, Wood had received a severe public tongue-lashing from Rosecrans for not moving his troops fast enough. ‘What is the meaning of this, sir? You have disobeyed my specific orders,’ Rosecrans had shouted. ‘By your damnable negligence you are endangering the safety of the entire army, and, by God, I will not tolerate it! Move your division at once as I have instructed, or the consequences will not be pleasant for yourself.’

With Rosecrans’ stinging rebuke still echoing in his ears, Wood was not about to be accused of moving too slowly again, even though this new order confused him. Wood knew there was no gap in the Union line. Brannan had been on his left all along. To comply with the commanding general’s order, Wood was required to pull his two brigades out of line, march around Brannan’s rear, and effect a junction with Reynolds’ right. In carrying out this maneuver, Wood created a gap where none had existed.

Simultaneously, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan’s men were ordered out of line on Wood’s right and sent to bolster the threatened left wing, and Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’ division was ordered into the line to fill the quarter-mile hole vacated by Wood. Almost three full divisions of the Federal right wing were in motion at the same time, in the face of a heavily concentrated enemy.

Now, completely by chance, in one of those incredible situations on which turn the fortunes of men and nations, Longstreet unleashed a 23,000-man sledgehammer attack directed right at the place where Wood had been moments earlier.

At 11:30 a.m., the gray-clad legion sallied forth from the forest across LaFayette Road into the fields surrounding the little log cabin of the Brotherton family. Almost immediately it came under fire from Brannan’s men, still posted in the woods across the road. Brannan checked Stewart in his front and poured an unsettling fire into the right flank of the advancing Confederate column. Davis’ Federals, arriving from the other side, hit the Rebels on their left while his artillery began tearing holes in the ranks of the attackers.

Johnson soon realized that the heavy resistance was coming from the flanks and the firing of scattered batteries. His front was virtually clear of opposition, and he smartly ordered his troops forward at the double-quick. As he emerged from the treeline that marked Wood’s former position, Johnson saw Davis’ troops rushing forward to his left, while two of Sheridan’s brigades were on their way north towards Thomas. On Johnson’s right, Wood’s two brigades were still in the act of closing on Reynolds.

While Johnson wheeled to the right to take Wood’s trailing brigade and Brannan from behind, Hindman bowled into Davis and Sheridan, throwing them back into confusion. When Brannan gave way, Brig. Gen. H.P. Van Cleve’s division was left exposed and joined the flight from the field. In a flash of gray lightning, the entire Union right disintegrated.

The onrushing Confederates were driving a wedge far into the Federal rear. They crossed the Glenn-Kelly Road just behind the Brotherton field, rushed through heavy stands of timber, and burst onto the open ground of the cultivated fields of the Dyer farm. One Confederate regiment overran a troublesome Union battery that had been firing from the Dyer peach orchard, capturing all nine of its guns.

Johnson paused to survey the progress of the attack. Everywhere, it seemed, Union soldiers were on the run, fleeing in panic over the countryside and down the Dry Valley Road toward McFarland’s Gap, the only available avenue to reach the safety of Chattanooga. ‘The scene now presented was unspeakably grand,’ the amazed general recalled.

The brave but often reckless Hood caught up with Johnson at the Dyer farm and urged him forward. ‘Go ahead and keep ahead of everything,’ Hood shouted, his left arm still in a sling from a wound received 10 weeks earlier at Gettysburg. Moments later, Hood was hit again. This time, a Minie bullet shattered his right leg. He fell from his horse and into the waiting arms of members of his old Texas Brigade, who carried him to a field hospital, where the leg was amputated. Meanwhile, Longstreet was ecstatic as his troops swept the men in blue before them. ‘They have fought their last man, and he is running,’ he exclaimed.

Only two Federal units offered resistance of greater than company strength once the rout was on. Intrepid Colonel John T. Wilder and his brigade of mounted infantry assailed Hindman’s exposed flank and drove Brig. Gen. Arthur Manigault’s brigade back nearly a mile from the area of the breakthrough. Wilder’s stouthearted troopers from Indiana and Illinois were able to delay a force many times their size by employing the Spencer repeating rifle.

Sheridan’s only remaining brigade, under Brig. Gen. William Lytle, a well-known author and poet, was in the vicinity of the Widow Glenn house when Hindman’s Confederates began streaming through the woods. A commander much admired by his troops, Lytle was famous for his prewar poem, ‘Antony and Cleopatra,’ which was popular in the sentimental society of the day and familiar to soldiers on both sides.

Lytle found his brigade found his brigade almost completely surrounded by Rebels. With the prospect of a successful withdrawal slim, he gallantly ordered his men to charge. He told those near him that if they had to die, they would ‘die in their tracks with their harness on.’ As he led his troops forward, he shouted: ‘If I must die, I will die as a gentleman. All right, men, we can die but once. This is the time and place. Let us charge.’ Lytle was shot in the spine during the advance but managed to stay on his horse. Then, he was struck almost simultaneously by three bullets, one of which hit him in the face. As the doomed counterattack collapsed around him, the steadfast Lytle died.

Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana was with the Army of Cumberland at Chickamauga to continue a series of reports to Washington on the progress of the Western war. Exhausted by the rapid succession of events the prior day, Dana had found a restful place that fateful morning and settled down in the grass to sleep. When Bushrod Johnson’s soldiers came crashing trough the Union line, he was suddenly wide awake. ‘I was awakened by the most infernal noise I ever heard,’ he remembered. ‘I sat up on the grass and the first thing I saw was General Rosecrans crossing himself–he was a very devout Catholic. ‘Hello!’ I said to myself, ‘if the general is crossing himself, we are in a desperate situation.”

Just then Rosecrans rode up and offered Dana some advice. ‘If you care to live any longer,’ the general said, ‘get away from here.’ The whistling of bullets grew steadily closer, and Dana now looked upon a terrible sight. ‘I had no sooner collected my thoughts and looked around toward the front, where all this din came from, than I saw our lines break and melt way like leaves before the wind.’ He spurred his horse toward Chattanooga, where he telegraphed the news of the disaster to Washington that night.

With time, the Confederate onslaught gained momentum, sweeping before it not only the Federal rank and file but also Rosecrans himself and two of his corps commanders, Crittenden and McCook. After negotiating the snarl of men, animals and equipment choking the Dry Valley Road, Rosecrans and his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. and future president James A. Garfield, stopped for a moment. Off in the distance, the sounds of battle were barely audible. Rosecrans and Garfield put their ears to the ground but were still unable to satisfy themselves as to the fate of Thomas and the left wing of the Union army.

Originally, Rosecrans had decided to go to Thomas personally and ordered Garfield to Chattanooga to prepare the city’s defenses. Garfield disagreed. He felt that Rosecrans should supervise the placement of Chattanooga’s defenders, while the chief of staff would find out what happened to Thomas. Rosecrans assented and started toward Chattanooga while Garfield moved in the direction of the battlefield. By the time he reached his destination, Rosecrans was distraught. He was unable to walk without assistance and sat with his head in his hands.

Had he known the overall situation, Rosecrans might have been in a better state of mind–if only slightly. Thomas, to the great good fortune of the Union cause, was far from finished. Those troops which had not fled the field had gathered on the slope of a heavily wooded spur that shot eastward from Missionary Ridge. From this strategic location, named Snodgrass Hill after a local family, Thomas might protect both the bulk of the army withdrawing through the ridge at McFarland’s Gap and the original positions of the Union left–if only his patchwork line could hold.

An assortment of Federal troops, from individuals to brigade strength, came together for a last stand. Virtually all command organization was gone, but the weary soldiers fell into line hurriedly to meet an advancing foe flush with victory. The Rebels drew up around the new defensive position, and a momentary lull settled over the field.

Their goal clearly before them, the emboldened Confederates then rose in unison and assailed their enemy with renewed vigor. They pressed to within feet of the Union positions, only to be thrown back again and again, leaving scores of dead and wounded on the ground behind them.

With three of Longstreet’s divisions pressing him nearly to the breaking point, Thomas noticed a cloud of dust and a large body of troops moving toward him. Was it friend or foe?

When the advancing column neared, Thomas had his answer. It was Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger with two brigades of the Union army’s reserve corps under Brig. Gen. James Steedman. These fresh but untried troops brought not only fire support but badly needed ammunition to the defenders of Snodgrass Hill, who had resorted to picking the cartridge boxes of the dead and wounded. For two days, Granger had guarded the Rossville Road north of the battlefield. By Sunday afternoon, he was itching to get into the fight. Finally, when he could stand it no longer, he bellowed, ‘I am going to Thomas, orders or no orders.’

At one point, the marauding Rebels actually seized the crest of Snodgrass Hill, planting their battle flag upon it. But thanks to numerous instances of individual heroism, the stubborn Yankees heaved them back. No single act of bravery was more spectacular than that of Steedman himself, who grabbed the regimental colors of a unit breaking for the rear and shouted: ‘Go back boys, go back. but the flag can’t go with you!’

As daylight began to fade, Thomas rode to the left to supervise the withdrawal of his remaining forces from the field, leaving Granger in command on Snodgrass Hill. Longstreet had committed Preston’s division in an all-out final attempt to carry the position, and the movement toward McFarland’s Gap began while Preston’s assaults were in progress. The protectors of Snodgrass Hill were out of ammunition again, and Granger’s order to fix bayonets and charge flashed along the lines of the 21st and 89th Ohio and the 22nd Michigan, the last three regiments left there. The desperate charge accomplished little save a few extra minutes for the rest of the army. While the last 563 Union soldiers on the hill were rounded up by Preston’s Confederates, the long night march to Chattanooga began for those fortunate enough to escape. By Longstreet’s own estimate, he had ordered 25 separate assaults against Thomas before meeting with success.

The tenacity of the defense of Horseshoe Ridge bought the Army of the Cumberland precious time. It also contributed to Bragg’s unwillingness to believe his forces had won a great victory and might follow it up by smashing into the demoralized Federals at daybreak. Not even the lusty cheers of his soldiers all along the line were enough to convince their commander. Bragg was preoccupied with the staggering loss of 17,804 casualties, 2,389 of them killed, 13,412 wounded and 2,003 missing or taken prisoner. The Union army, after suffering 16,179 casualties, 1,656 dead, 9,749 wounded and 4,774 missing or captured, retired behind Chattanooga’s defenses without further molestation.

History has been less than kind to Bragg, not without cause. True enough, over a quarter of his effective force was lost at Chickamauga. Nevertheless, at no other time in four years of fighting was there a greater opportunity to follow up a stunning battlefield triumph with the pursuit of such a beaten foe. Had Bragg attacked and destroyed Rosecrans on September 21, there would have been little to stop an advance all the way to the Ohio River. Bragg, however, was true to form. As at Perryville and Murfreesboro before, he quickly allowed victory to become hollow.

Rosecrans, on the other hand, had seen one mistaken order wreck his military reputation and almost destroy his army. His nearly flawless campaign of the spring and summer had ended with the Army of the Cumberland holed up in Chattanooga and the enemy tightening the noose by occupying the high ground of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. Lincoln lost faith in ‘old Rosey’s’ ability to command, saying he appeared’stunned and confused, like a duck hit on the head.’

Chickamauga, the costliest two-day battle of the entire war, proved a spawning ground of lost Confederate opportunity. While Bragg laid siege to Chattanooga with an army inadequate to do the job, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the hero of Vicksburg, was given overall command in the West and set about changing the state of affairs. Reinforcements poured in from east and west. During the November campaign to raise the siege, the Army of the Cumberland evened the score with the rebels in an epic charge up Missionary Ridge. And when Union soldiers next set foot on the battlefield of Chickamauga, they were on their way to Atlanta.

This article was written by Mike Haskew and originally appeared in America’s Civil War magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!