Sixty Octobers ago, a quailing world stood at the verge of ending not with a whimper but a bang—actually, more than a few bangs, and very large bangs at that, courtesy of the nuclear warheads on missiles poised for launching by the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, not necessarily in that order. The elevator pitch: earlier that year the USSR, intent on evening the odds posed by an overwhelmingly more powerful American armamentarium, had smuggled a raft of rockets and nuclear warheads and accompanying materiél, aircraft, vehicles, and equipment, plus 43,000 Red Army personnel, into revolutionary Cuba. The hijinks that ensued when the Americans realized what was up spawned a nerve-wracking standoff of nearly two weeks’ duration, featuring a naval quarantine and talk of first strikes and mutually assured destruction until Premier Nikita Khrushchev did as President John Kennedy demanded and hauled his hardware home, caroming the superpowers toward talks on arms limitation. In The Abyss, prolific and skilled historian Max Hastings brings alive that much-told and ever-sobering tale with élan and immediacy, constructing a gripping, multifaceted tick-tock that gets under way well before those 13 notorious days and reaches well past the confrontation’s conclusion, extracting current-day lessons aplenty.

The Cuban missile crisis has never wanted for chronicling and re-chronicling, whether en passant in volumes about the Cold War and the ’60s at large or front and center in histories of the event itself, especially as time has done its work and official documents have leached from under lock and key, and private papers, memoirs, diaries, and other sources have come to light. In 2021, Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy, having made brilliant use of improved access to Soviet-era Russian archives, delivered the terrific Nuclear Folly: A New History of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which yanked readers into the vortex for an intimate, horrifying ride. Now Hastings, his research handicapped by the pandemic but game as ever, takes his innings, swings for the fences, and connects with a version that operates on a broader, deeper, and equally satisfying scale.

Appropriately for a Briton, Hastings, like a crack bowman, nocks his arrowing prose and lets fly a long and richly fascinating shot. He begins Abyss with a Cold War timeline and dramatis personae of players American, Soviet, and Cuban, then thumbnails the clown-car U.S. Central Intelligence Agency-run “invasion” of Cuba in April 1961 that ushered President John F. Kennedy into the realm of reality after all his tough campaign talk regarding missile gaps and softness on communism. JFK soon would be grasping what it really meant to “oppose any foe.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

By way of context, Hastings addresses Cuba’s centuries beneath Spanish rule and subsequent neocolonial existence under its northern neighbor’s thumb, personified by the 45 square miles of Cuba given over by treaty to an American military base at Guantánamo. American influence germinated the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, whose excesses triggered the 1959 revolution that Fidel Castro and his bearded legions wrought. Briefly the apple of the American eye—no less than TV variety show host Ed Sullivan hugged him on camera one Sunday night—Castro abruptly turned sharp left, nationalizing American businesses and cozying up to the USSR. In no time, the United States was trying to bring down, even kill Castro and destroy his regime, propelling the Cuban further into the Soviet sphere, a transition the Bay of Pigs completed. Now Fidel feared a full-bore American invasion and called for Soviet muscle to defend against it.

Castro’s demands exactly suited Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, who was spoiling for a confrontation. Riding high on his country’s initial vaulting successes in space but secretly and painfully aware of the Soviets’ distant secondary status in the nuclear sweepstakes, Khrushchev was bristling. The Americans and their allies were refusing to bow to Russian insistence that they quit Berlin, since 1945 a divided city maintained as a knob of Western willfulness deliberately poked into East Germany.

By treaty the Americans had openly installed across Britain, Europe, and even in Turkey high-powered missiles able to nuke Russian cities. To tilt matters his way, Khrushchev decided to equip Cuba—on the sly—with nuclear-tipped missiles and see how the Americans liked having the mortal tables turned.

Hastings foreshadows the actual undertaking with a rigorous chapter entitled “Mother Russia” delineating factors that induced Khrushchev to make his bold wager: Russia’s ingrained historical fear of invasion from the west, the profound and lingering consequences of Joseph Stalin’s rule and the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet state’s export of socialist revolution, the inevitable rivalry with the United States, the space race, the 1960 downing of an American U-2 spy plane over the Motherland, and multiple Berlin crises but especially Russia’s August 1961 installation of a wall to keep East Berliners red. The wall outraged the West by splitting the once and future German capital. Hastings brings to light previously well-hidden episodes of state violence visited upon dissenting Russians, as when residents of the Cossack city of Novocherkassk in June 1962 rioted over food shortages and labor grievances and for their obstinacy were massacred.

Against this helter-skelter backdrop, Khrushchev, painted by Hastings as an anxiety-ridden and mendacious butterball, opted to sneak a stash of nuclear mischief onto the newly reddened isle that the megalomaniacal Fidel Castro had been ruling for less than two years.

The premier’s goal: shock and amaze the American president. The younger man, whom Khrushchev thought a callow fellow, proved to have the steel and wisdom required to stand fast not only against his opposite number’s oafish bluster but that of his own military advisers and give Khrushchev the psychic elbow room to see reason. You may think you know the missile crisis story, but Hastings’s research and narrative skills will prove otherwise. His cinematic intercutting among scenes in Washington, Moscow, and Havana from the crisis that seemed about to end all crises will startle even the most deeply dedicated follower of Cold War history. If some streaming studio is not angling to option The Abyss for a dramatic series, I’ll eat a jar of fallout shelter peanut butter. —Michael Dolan is editor of American History.

This book review appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of American History magazine.

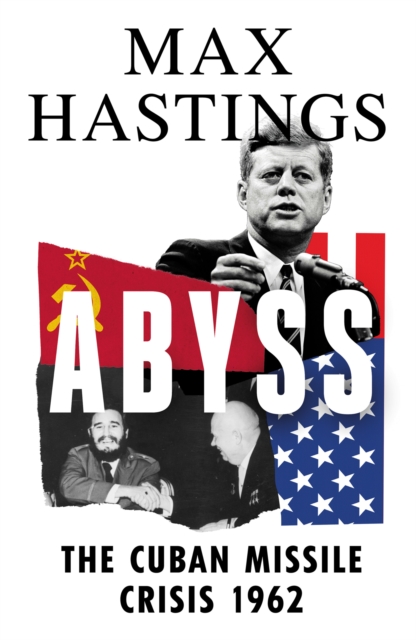

The Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis 1962

By Max Hastings

HarperCollins, 2022