Artemisia absinthium is a green, leafy plant native to Europe, but one that has since migrated to North America. Commonly called the wormwood plant, its flowers and leaves are the main ingredient of absinthe, one of the world’s most unusual liquors that was first distilled in Switzerland. Absinthe is naturally green in color, and potent, usually 90 to 148 proof.

That potency led many to believe absinthe had hallucinogenic powers, and controversy has plagued the drink since it was first distilled. Before coming to America, it was extremely popular in France. And then, Jean Lanfray killed his family after imbibing the “Green Demon.”

The Lanfray killings happened in Commugny, a small agricultural village in southwest Switzerland, nestled along the border with France. Lanfray was a tall, brawny vineyard worker and day laborer. Like many in the area, he was a born Frenchman; he had served three years in the French Army. At 31 years old, he lived in a two-story farmhouse with his family: his wife and two daughters living upstairs, and his parents and brother, with rooms downstairs.

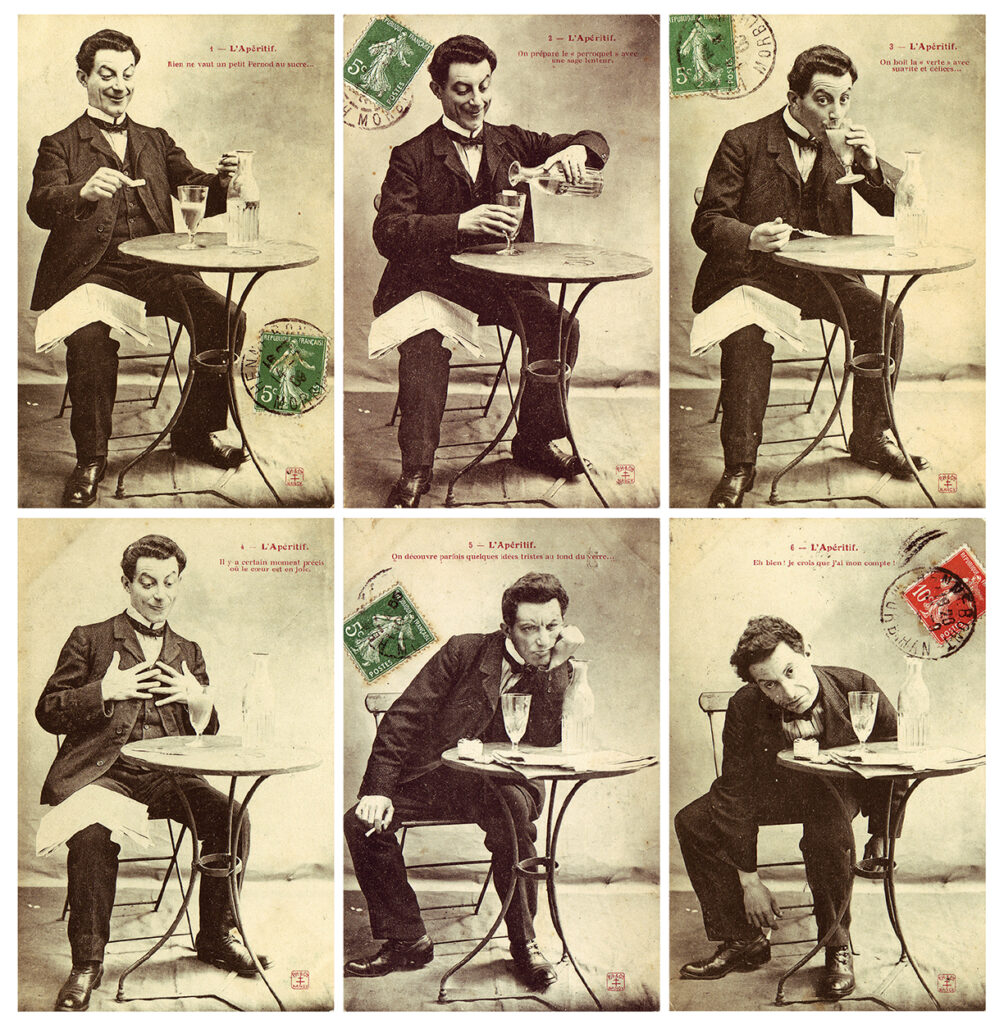

On August 28, 1905, he woke at 4:30 in the morning. He started the day with a shot of absinthe diluted in water—not uncommon for him or for many Europeans at the time. He let the cows out to pasture, had some harsh words with his wife, and set off to a nearby vineyard to work. Along the way, he stopped for more alcohol: a creme de menthe with water, followed by a cognac and soda. By then it was 5:30 a.m.

Investigating the killings, Swiss authorities established a careful timeline of Lanfray’s prodigious drinking, learning that he would sometimes drink five liters of wine a day. Around noon, he lunched on bread, cheese, and sausage. He also had six glasses of strong wine over his lunch and afternoon break. And another glass before leaving work about 4:30 p.m.

At a cafe on his way home, he had black coffee with brandy. Back at the farmhouse, he and his father each polished off another liter of wine while Lanfray bickered with his wife. Their long-simmering grievances came to a head, and he rose from his seat, took down his rifle from the wall, and shot his wife through the forehead, killing her instantly.

As Lanfray’s father ran from the house seeking help, his daughter Rose came into the room—Lanfray shot her in the chest. He then went to the crib of his younger daughter, Blanche, and killed her, as well. He struggled to kill himself with the rifle, but it was too long to easily aim at himself and still reach the trigger. Using a piece of string, he finally pulled the trigger but succeeded only in shooting himself in the jaw. With blood running down his face, he picked up Blanche and carried her to the barn, where he lost consciousness. Police found him minutes later.

It was a senseless tragedy, the kind that leaves bystanders helplessly grasping at explanations. The fact that a man could get drunk, kill his entire family, and have no memory of it—that may have struck too close to home for Lanfray’s neighbors, who worked in vineyards and drank beside him. No, there had to be something else, something other.

At a public meeting soon after, the people of Commugny railed against the supposedly corrupting power of absinthe. Lanfray was known regularly to drink it (as did many, many others), and had drunk two glasses on the day of the murders (along with liters of wine). A story began to form, an explanation. Lanfray wasn’t simply an angry drunkard; he was an Absintheur.

It was a story many were ready to hear. Absinthe already had a dangerous reputation, despite its widespread use throughout Europe. Even aficionados cautioned that “absinthe is a spark that explodes the gunpowder of wine.”

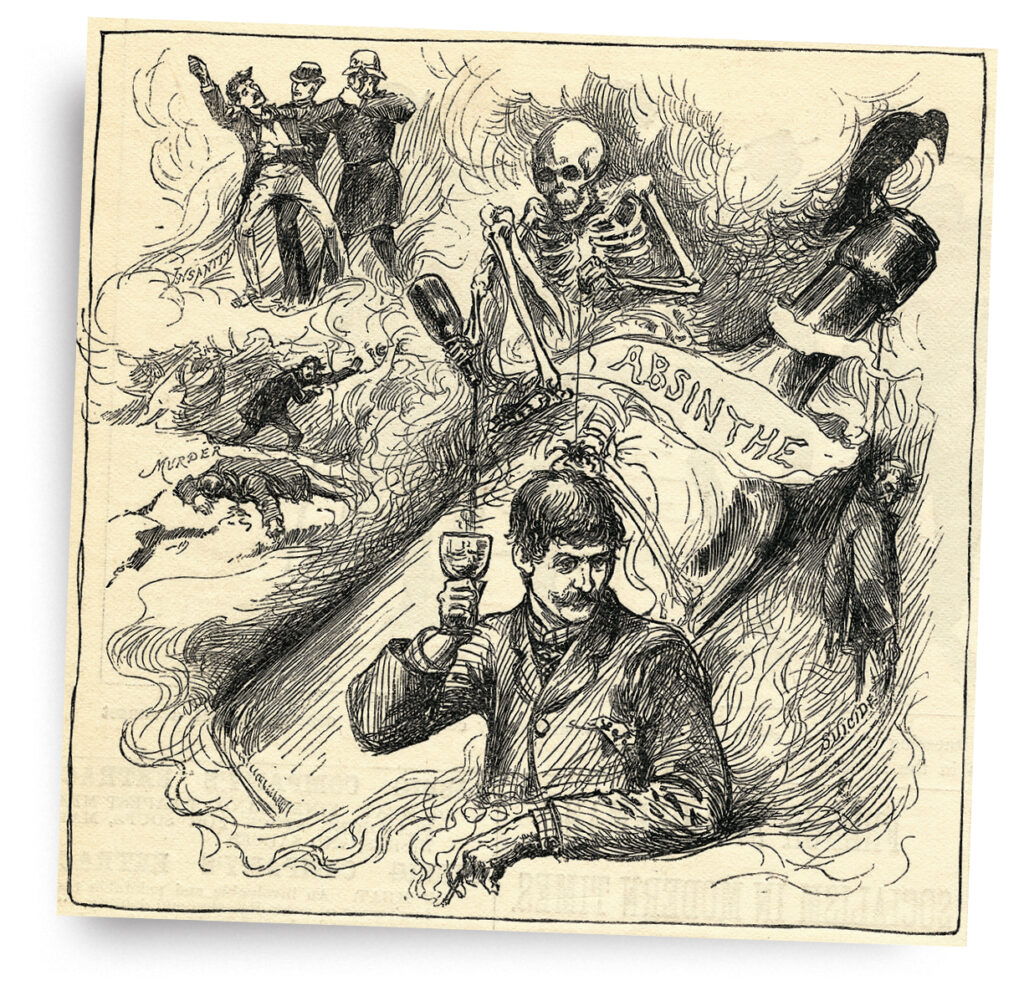

Lanfray’s killings provided potent fuel for a moral panic around absinthe that had been growing for decades. Politicians now had a scapegoat—and a crusade. The press feverishly covered “the Absinthe Murder,” putting it on front pages throughout Europe. One Swiss newspaper called absinthe “the premier cause of bloodthirsty crime in this century,” a sentiment echoed by Commugny’s mayor, who declared, “Absinthe is the principal cause of a series of bloody crimes in our country.”

In the region, a petition to outlaw the drink gathered 82,000 signatures within weeks. After an absinthe drinker in Geneva, Switzerland, killed his wife with a hatchet and a revolver, an anti-absinthe petition quickly gained 34,702 signatures. The public, too, had found a villain.

The following February, Lanfray went on trial. His defense hinged on proving him absinthe-mad, consumed by his addiction to that foul drink whose demonic grip had driven him to murder. If absinthe had made him do it, he couldn’t be held completely responsible for his actions.

The argument leaned on a folk understanding of “absinthism,” a collection of maladies supposedly known to afflict the chronic absinthe drinker, including seizures, speech impairment, disordered sleep, and auditory and visual hallucinations. Absinthism was the road to insanity and death; even as millions of people from every walk of life enjoyed absinthe, medical professionals and the press warned of asylums rapidly filling with former Absintheurs, now lost in the throes of madness.

It was known as “une correspondance pour Charenton,” a ticket to Charenton, the insane asylum outside Paris. (It’s unclear whether absinthism actually existed as a syndrome at all, rather than arising from misunderstandings about alcoholism and mental health more generally.)

Not every doctor gave credence to the more lurid claims about absinthism. In Lanfray’s case, however, Albert Mahaim, a professor at the University of Geneva and the head of the regional insane asylum in Vaud, examined the defendant in jail and later testified that “without a doubt, it is the absinthe he drank daily and for a long time that gave Lanfray the ferociousness of temper and blind rages that made him shoot his wife for nothing and his two poor children, whom he loved.” The prosecution, naturally, disagreed.

Whatever the public sentiment toward absinthe, Lanfray was found guilty on four counts of murder—his wife, it turned out, had been pregnant with a son. Three days later, Lanfray hanged himself in his cell.

Less than a month after his death, Vaud, the canton containing Commugny, succeeded in banning absinthe, with the canton of Geneva quickly following. Then it was banned nationwide. Belgium had already banned absinthe in 1905; the Netherlands in 1909. Even France, which consumed more absinthe than the rest of the world, and where it was, as historian P.E. Prestwich put it, “inspiration of French poets and the consolation of French workers,” banned the drink in 1914.

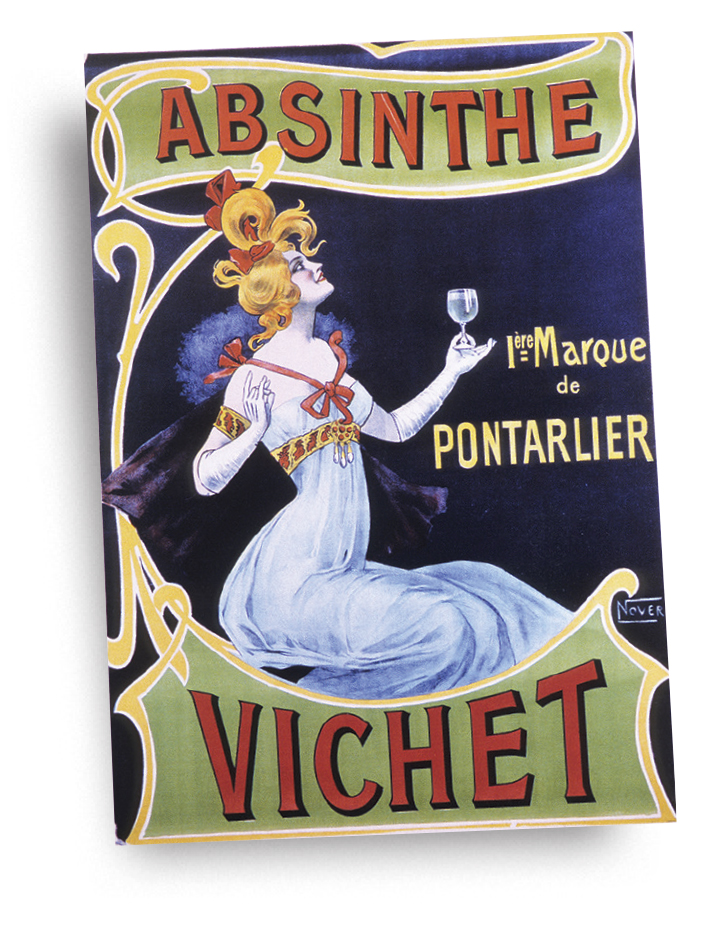

The Green Fairy to its advocates and the Green Demon to its detractors, absinthe was exiled from much of Europe. (The United Kingdom and the Czech Republic were notable exceptions.) While anti-alcohol movements had agitated in countries around the world for decades, absinthe was the first alcoholic drink singled out for a ban. Its outsized, bewitching reputation had been turned against it.

Before the exile, absinthe had a long history in Europe, particularly in France. In its modern form, it likely began as a patent remedy concocted by a French doctor living in Switzerland in the late 1700s. Its name derives from the Greek absinthion, an ancient medicinal drink made by soaking wormwood leaves (Artemisia absinthium) in wine or spirits. It was said to aid in childbirth, and the Greek physician Hippocrates, known as the father of medicine, recommended it for menstrual pain, jaundice, anemia, and rheumatism.

Wormwood persisted as a folk remedy through the ages; when the bubonic plague ravaged England in the 17th and 18th centuries, desperate villagers burned wormwood to cleanse their houses. Wormwood drinks were likewise medicinal—including that early patent remedy.

In 1830, France conquered Algeria and began to expand its empire into North Africa. Soon 100,000 French troops were stationed in the country, where the heat and bad water led to sickness tearing through the occupiers. Wormwood helped stave off insects, calm fevers, and prevent dysentery, and soldiers started adding it to their wine. When they returned home, they brought with them “une verte”—the potent drink with the unique green color.

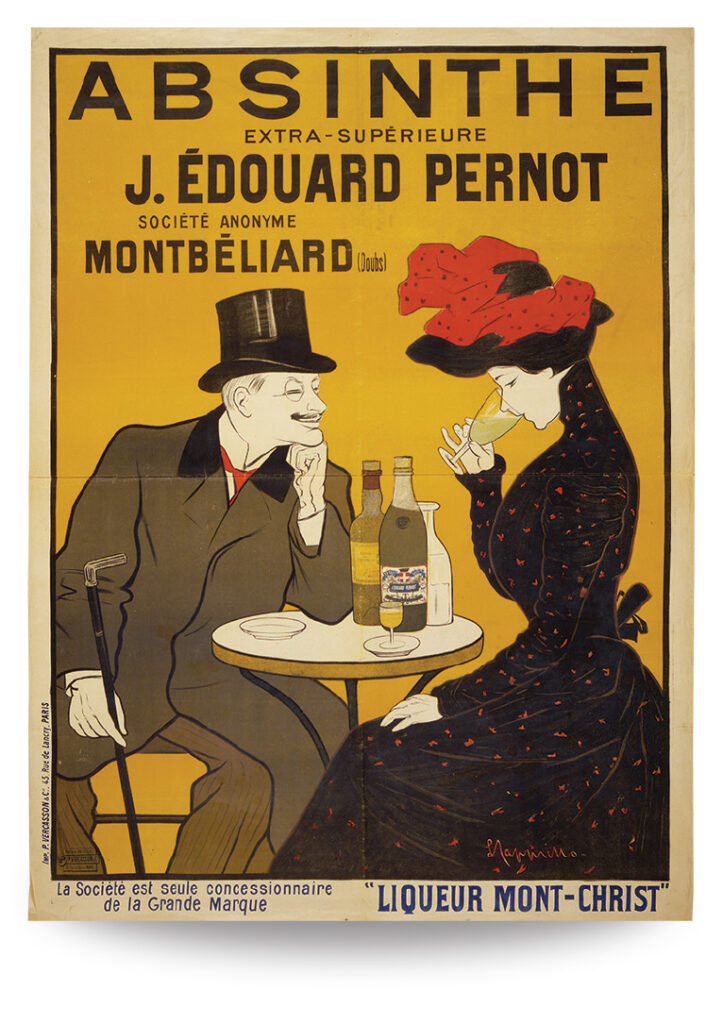

Absinthe quickly became intertwined with French society, first as a harmless vice of the upper and middle classes. As its reputation (exotic, revelatory) grew, so did its popularity; even among those not looking for a hallucinogenic experience, the high alcohol content proved a key selling point, as you could easily dilute absinthe and still get a great bargain, proof-wise. Everywhere in France seemed to celebrate l’heure verte, the “green hour” of the early evening devoted to absinthe.

Absinthe became intricately connected to French culture and identity. So it is no surprise that when the drink found its way to the United States, the most famous venue for absinthe indulgence would be in a city with a distinctly French flavor: New Orleans, “the little Paris of North America.”

The French sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803, and the region’s uniquely French culture became a point of pride. As absinthe took off in France, it also appeared in New Orleans, though without the same fanfare and popularity. In a town already famous for carousing, absinthe was one drink among many.

Following the Civil War, a barman named Cayetano Ferrer, formerly of the Paris Opera House, began serving absinthe in what some clever marketing called “the Parisian manner.” A glass of the emerald drink would be placed on the bar beneath a pair of fountains, and water would slowly drip, creating a milky opalescence in a glass—a process called the “louche.”

Ferrer’s ritual proved a compelling spectacle for the tourists who flocked to the city of sin. The building became the Old Absinthe House. Thought to be the city’s first saloon, it hosted famous luminaries from Mark Twain and Walt Whitman to O. Henry and William Makepeace Thackeray. Oscar Wilde, of course, attended. No visit to New Orleans, by then “the Absinthe capital of the world,” could be complete without a round at the Old Absinthe House.

While Europeans of all classes drank absinthe, in the United States it remained a cosmopolitan indulgence little known outside the city. New York had its own Absinthe House, and large metropolitan areas such as Chicago and San Francisco catered to the artists, bohemians, and wealthy, gilded-age poseurs who wanted to associate themselves with absinthe’s dark allure.

Absinthe’s relative obscurity in America didn’t prevent the press from warning of its fearsome reputation, however. Against the backdrop of a growing temperance movement, in 1879, a Dr. Richardson offered his perspective on absinthe to The New York Times. “I cannot report so favorably on the use of Absinthe as I have on the use of opium,” he began, describing rising absinthe use in “closely-packed towns and cities.” He warned that the drink was commonly adulterated, and that frequent imbibers could become addicted. “In the worst examples of poisoning from Absinthe,” he wrote, “the person becomes a confirmed epileptic.”

Later that year, the Times reiterated: “The dangerous, often deadly, habit of drinking Absinthe is said to be steadily growing in this country, not among foreigners merely, but among the native population.” It ascribed “a good many deaths in different parts of the country” to a drink “much more perilous, as well as more deleterious, than any ordinary kind of liquor.”

Absinthe, the writer claimed, had a subtlety lacking in other alcohol; addiction could sneak up quickly. “The more intellectual a man is,” the Times cautioned, “the more readily the habit fastens itself upon him.” It had already taken its toll in Europe: “Some of the most brilliant authors and artists of Paris have killed themselves with absinthe, and many more are doing so.” The Times closed by warning that absinthe, previously found only in large cities, had permeated everywhere, “and it is called for with alarming frequency.”

Much of absinthe’s mythology came from an accumulation of confusions, misunderstandings, and motivated lies. Some, though, did try to cut through the green fog and get to the truth—at least as best they could. Valentin Magnan, physician-in-chief at Sainte-Anne, France’s main asylum, saw rising numbers of insane people as a sign of his country’s social decay. (More likely, the increase resulted from improved diagnostic techniques.) Like many, he saw absinthe as the culprit, and set out to prove his case.

In 1869 he published his results. He had arranged an experiment. One guinea pig was placed in a glass case with a saucer of pure alcohol; another was placed in a glass case with a saucer of wormwood oil. A cat and a rabbit also got their own cases and their own saucers of wormwood oil. The animals breathing wormwood fumes were wracked with seizures, while the sole alcohol-breathing guinea pig just got drunk.

This and other experiments convinced Magnan (if he hadn’t been already) that absinthe was uniquely toxic. He extrapolated his results to humans, and claimed that “absinthistes” in his asylum displayed seizures, violent fits, and amnesia. He pushed for banning the Green Demon.

Fellow authorities disagreed, pointing out that guinea pigs inhaling high doses of distilled wormwood couldn’t be compared to humans consuming tiny amounts of diluted wormwood. They suggested that wormwood likely had little effect, and whatever damage absinthe wrought was no different from typical alcoholism. Rhetorically, however, Magnan’s support for the concept of “absinthism,” separate from alcoholism, enabled those concerned citizens who wanted to ban absinthe without committing to full prohibition. Absinthe, after all, posed a unique medical danger, while other alcohol (including France’s beloved wine) was surely fine for responsible adults.

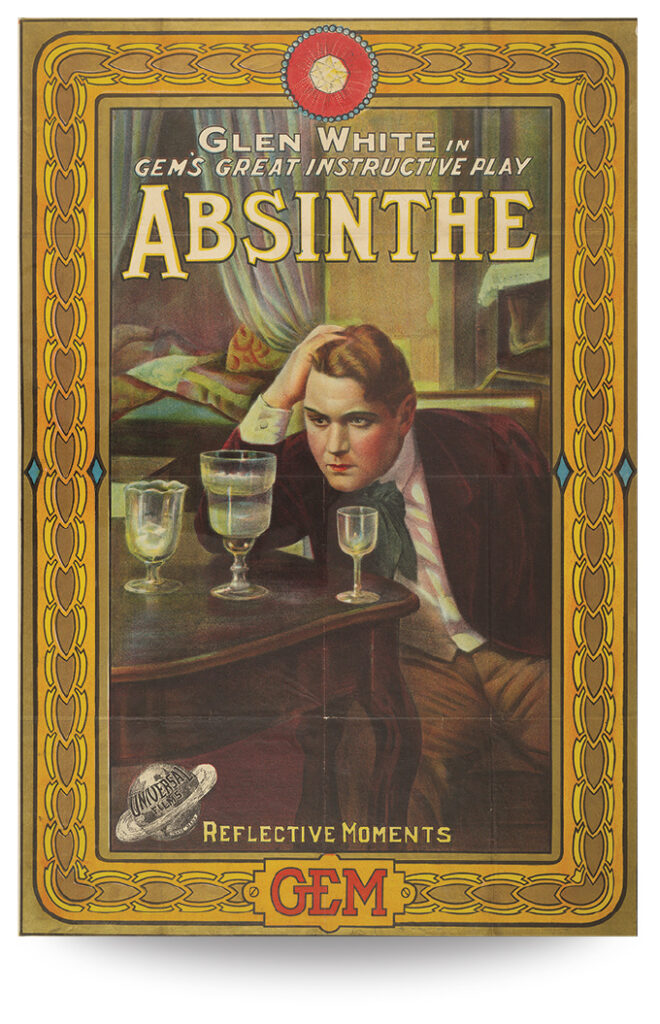

In the United States, absinthe never became the burning social question it was in Europe. The media took occasional potshots, reflecting a general sense of absinthe’s depravity, without ever raising banning it to the height of a moral crusade.

An 1883 cartoon in Harper’s Weekly, for example, had the caption, “Absinthe Drinking—The Fast Prevailing Vice Among Our Gilded Youth.” The picture above featured a strapping young man on the left, and on the right a broken, aged specter of dissolution, “after two years’ indulgence, three times a day.” An earlier article in the magazine declared: “Many deaths are directly traceable to the excessive use of absinthe. The encroachments of this habit are scarcely perceptible. A regular absinthe drinker seldom perceives that he is dominated by its baleful influence until it is too late. All of a sudden he breaks down; his nervous system is destroyed, his brain is inoperative, his will is paralyzed, he is a mere wreck; there is no hope of his recovery.”

In the early 1900s, public opinion in Europe began to turn against absinthe, generally as part of the long-simmering temperance movement, and more specifically because of the Lanfray murders. As countries began to ban the drink, Harper’s Weekly reported in 1907 that the U.S. Department of Agriculture had begun to investigate “the green curse of France.” Four years later, with little fanfare at the end of 1911, the department’s Pure Food Board announced starting January 1, 1912, importing absinthe into the United States would be prohibited.

Give it a shot!

Tenth Ward distilling in Frederick, Md., is one American distiller now

producing absinthe. Check them out at (tenthwarddistilling.com).

The head of the board told the Times that “Absinthe is one of the worst enemies of man, and if we can keep the people of the United States from becoming slaves to this demon, we will do it.” (The board also announced new restrictions on opium, morphine, and cocaine.)

News reports from the time show that, unsurprisingly, Americans didn’t immediately cease drinking absinthe. In a preview of the Prohibition era, authorities particularly in California seized caches of the emerald beverage. British mystic and provocateur Aleister Crowley wrote his famous paean to the Old Absinthe House, “The Green Goddess,” in 1916, well after the ban. “Art is the soul of life and the Old Absinthe House is heart and soul of the old quarter of New Orleans,” he wrote. And he struck a familiar note about the bewitching, destructive power of the Green Fairy: “What is there in Absinthe that makes it a separate cult? The effects of its abuse are totally different from those of other stimulants. Even in ruin and in degradation it remains a thing apart: its victims wear a ghastly aureole all their own, and in their peculiar hell yet gloat with a sinister perversion of pride that they are not as other men.”

Crowley’s line evoked a demimonde particular to that time and place, but in 1920 the arrival of Prohibition blunted much of absinthe’s mystique in the United States. Jad Adams writes: “The surreptitious nature of drinking in the prohibition era—serving alcohol from hip flasks, barmen squirting a syringe of pure alcohol into soft drinks they were serving—was not conducive to absinthe, which was a drink of display and provocation.”

New Orleans continued imbibing and became known as “the liquor capital of America.” The Old Absinthe House was closed by federal agents in 1925 and again in 1926, the 100-year anniversary of its opening. Yet it outlasted prohibition and remains a fixture of New Orleans culture to this day.

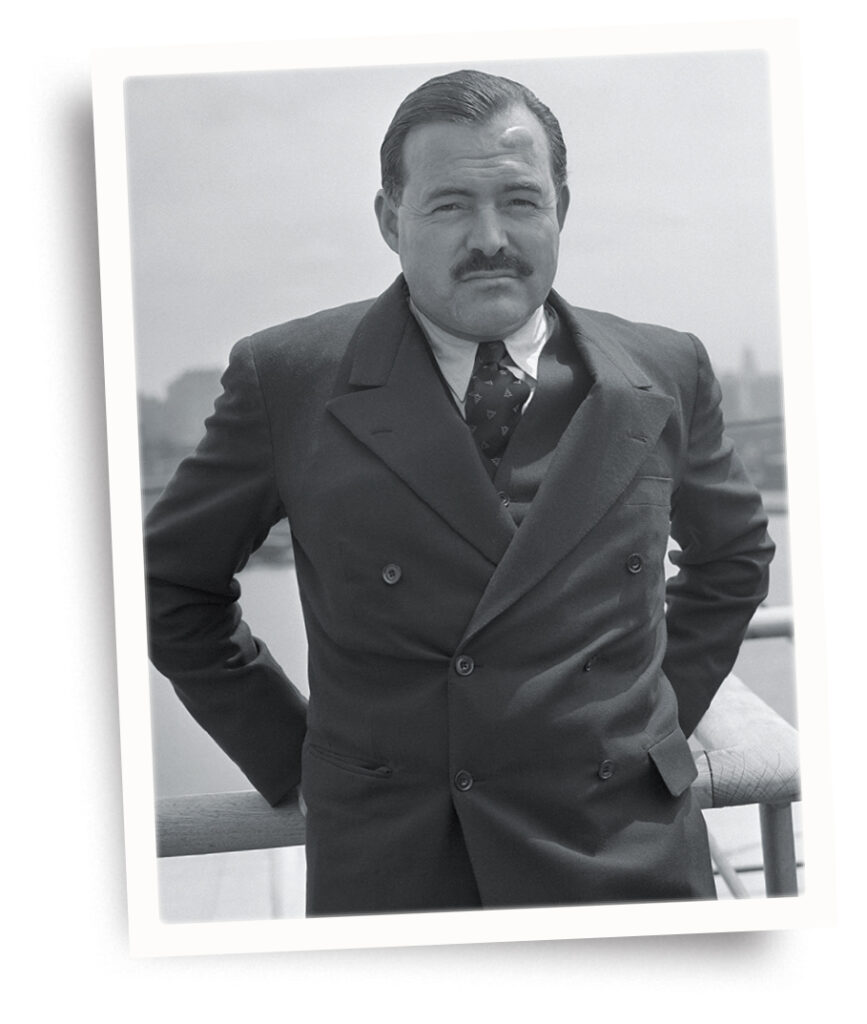

Absinthe, too, persevered. It went further underground, particularly in America, and that burnished its appeal among bohemians and the counterculture. Ernest Hemingway and Jack London fondly recalled their absinthe experiences beyond the reach of U.S. law; Hemingway’s cocktail, Death in the Afternoon, is likely the country’s most lasting and well-known contribution to absinthe culture.

And eventually, like green shoots emerging after a long and punishing winter, the Green Fairy rose again. After nearly 100 years of targeted prohibition, in 2007 the United States once again allowed absinthe to be imported and consumed. The green hour had come back around again, at last.

Jesse Hicks writes about science, technology, and politics. Based in Detroit, his work has appeared in Harper’s, Politico, The New Republic, and elsewhere.

How Do You Drink Absinthe?

(Ask Hemingway)

Well, it requires a fancy slotted spoon, for one thing. The following is the most traditional and common method for preparing the drink. You place a sugar cube on the spoon, and then place the spoon over a glass of absinthe. Pour iced water over the sugar cube so you end up with about 1 part absinthe and 3–5 parts water.

The water brings out the anise, which gives absinthe a licorice taste, and fennel that are also distilled with the leaves and flowers of the wormwood plant. If the mix is correct, the liquid will turn milky and opalescent in appearance.

Ernest Hemingway was a fan of absinthe—why is that not surprising? His favorite way to drink it was a simple cocktail he called “Death in the Afternoon,” the same name as his 1932 book about Spanish bullfighting.

Death in the Afternoon ingredients:

1½ ounces Absinthe

4 ounces chilled Champagne

Hemingway published the recipe in a 1935 book, So Red the Nose, or Breath in the Afternoon, which featured 30 drink concoctions from celebrities. He explained, “Pour one jigger Absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly.” Yes. Very slowly.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.