It now seems a distant memory, but in October 1998 a situation comedy set in the Civil War White House premiered on national television and promptly ignited a firestorm of outrage. The Secret Life of Desmond Pfeiffer offended just about everyone: critics, for what one called ‘jaw dropping witlessness; African Americans, for making a joke of slavery; feminists, for portraying Hillary Clinton as a sexual predator; and supporters of her husband, for transparently satirizing his problems with affairs, apologies, and grand juries.

Most of all–before it died a quiet death, the victim of anemic ratings—Desmond Pfeiffer offended admirers of Abraham Lincoln. The show reduced the Great Emancipator of legend to an inept, insensitive, sex-starved dolt. One scene actually depicted Lincoln fantasizing lasciviously about the brawny young male soldiers in the Union army.

The irreverence was enough to inspire an attendee at a Lincoln Family symposium at Robert Todd Lincoln’s Hildene estate in Manchester, Vermont, to circulate an irate petition demanding the show’s cancellation. The nature of this will dishonor the name and character of the man who has been rightly acclaimed our greatest national leader, the petition argued. We, the undersigned are highly indignant that television wishes to degrade Lincoln in any way. Irreverently portraying the 16th president, it maintained, constituted the desecration of an American saint, an insult to history, and a threat to national memory.

But was it? Forgotten by these and other angry viewers was a contrary historical truth: Abraham Lincoln had been dragged through the mud before, and often. He was mercilessly lampooned, viciously libeled, and relentlessly satirized in his own time–and his reputation not only survived but flourished. In fact, his stoic and good-natured response in the face of such stabs from the stiletto of malicious verbal and visual abuse made him seem nobler at the time, and greater in retrospect.

The national humor mill of the era made Lincoln its favorite grist. American humorists portrayed the Civil War, to paraphrase Lincoln, with malice toward one. And that one was Lincoln himself. His ungainly form, homely face, and awkward Western manner—not to mention his controversial policies—formed a combustible mixture that inflamed professional and political humorists.

This frequent butt of ridicule was comically maligned in the press, in books, and in cartoons published in the North as well as the South, in Europe as well as America. Desmond Pfeiffer was no exception; it was a return to the rule.

The mockery began as soon as Lincoln emerged as a national figure, following his unexpected nomination to the presidency in May 1860. Engravers and lithographers rushed to publish flattering portraits introducing the reputedly ugly candidate to a wary public. But as much as the Republicans sought to make virtues of Lincoln’s humble origins and miraculous rise, Democrats encouraged lampoons that mocked those very qualities. Often the same publishers who met the consumer demand for Lincoln portraits also made a lot of money churning out caricature sheets.

Such cartoons usually depicted Lincoln as a country bumpkin with a wild thatch of uncombed hair, clad in ill-fitting pantaloons and open-necked shirts, and wielding a log rail to ward off serious inquiries into his supposedly dangerous views on racial equality. Currier & Ives of New York may have crafted the quintessential 1860 campaign cartoon when they portrayed The Rail Candidate astride a log rail labeled Republican National Platform, being carried to the White House by supporters. It is true I have Split Rails, the uncomfortable nominee declares, but I begin to feel as if this Rail would split me, it’s the hardest stick I ever straddled. Coarser variations on the theme depicted him erecting log-rail camouflage to conceal n——s in the woodpile—metaphorically minimizing attention on the stormy slavery issue by focusing voters instead on his inspiring ascent from a log cabin to the White House.

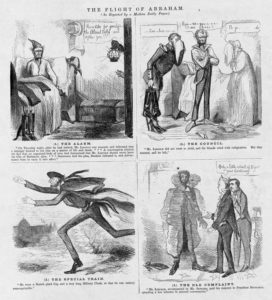

Lincoln had only himself to blame for inspiring the next wave of ridicule early the next year en route to his inauguration in Washington. By donning what security advisor Allen Pinkerton described as a soft low-crowned hat and a bob-tailed overcoat to avoid recognition in hostile Baltimore while changing trains in Baltimore, Lincoln invited charges that he was a coward. Exaggerating his disguise into a Scotch plaid Cap and a very long military Cloak, cartoonists at Harper’s Weekly issued a hilarious pictorial parody under the headline, The Flight of Abraham. One panel showed him quaking in fear so violently that Henry Seward, incoming secretary of state, explains to President James Buchanan that his successor is suffering only a little attack of ague. Assailing the sectional hostility that inspired the drastic evasive tactic in Baltimore, the pro-Republican New York Tribune was nonetheless forced to admit: It is the only instance recorded in our history in which the recognized head of a nation…has been compelled, for fear of his life, to enter the capital in disguise. More blunt was the denunciation by the Baltimore Sun:

Had we any respect for Mr. Lincoln, official or personal, as a man, or as President elect of the United States…the final escapade by which he reached the capital would have utterly demolished it…. He might have entered Willard’s Hotel with a head spring and a summersault, and the clown’s merry greeting to Gen. Scott, Here we are! and we should care nothing about it, personally. We do not believe the Presidency can ever be more degraded by any of his successors than it has by him, even before his inauguration.

A wave of anti-Lincoln pictorial lampoons now flooded the country—progressively exaggerating his Baltimore disguise until one example showed him as a bare-kneed Scotsman in a tam and kilt, dancing The MacLincoln Highland Fling. For years thereafter, the Scotch cap would remain a staple of anti-Lincoln caricature, a reminder that once he suffered the worst indignity a Victorian-era gentleman could ever face: a public questioning of his manly courage.

After the inauguration, Lincoln embarked on the deadly serious business of restoring the fractured American Union and managing the bloodiest military struggle in world history. Still, the humorous assaults continued unabated. Further inspiration came as more and more Americans learned that the president himself enjoyed—and often told—funny stories. As early as 1858, his rival in Illinois politics and debate, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, had acknowledged his prowess with a joke, admitting: “Nothing else—not any of his arguments or any of Lincoln’s replies to my questions—disturbs me. But when he begins to tell a story, I feel that I am to be overmatched.” Once Lincoln entered the White House, accounts of his fondness for storytelling spread nationwide.

Lincoln’s admirers loved his down-to-earth style and earthy way with a comic tale. But foes leaped on such qualities as evidence of Lincoln’s coarseness and lack of dignity. One cartoon of the day featured him reacting to news of wartime slaughter by drawling: That reminds me of a funny story. Such caricatures used humor to make Lincoln’s humor a political liability.

Criticism notwithstanding, Lincoln became an appreciative reader of the leading satirists of the day. He particularly enjoyed Charles F. Browne (who wrote under the pseudonym Artemus Ward), David R. Locke (Petroleum V. Nasby), and R. H. Newell (Orpheus C. Kerr). Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase remembered with huffy disbelief that the most momentous cabinet meeting of Lincoln’s entire administration—the one at which he announced he would issue his Emancipation Proclamation—began with the president reading a chapter from Artemus Ward’s latest book of stories and laughing heartily. If I did not laugh, Lincoln confided to a minister who questioned his irreverence, I should die. That others were laughing at him as well as with him seemed to bother him little, if at all.

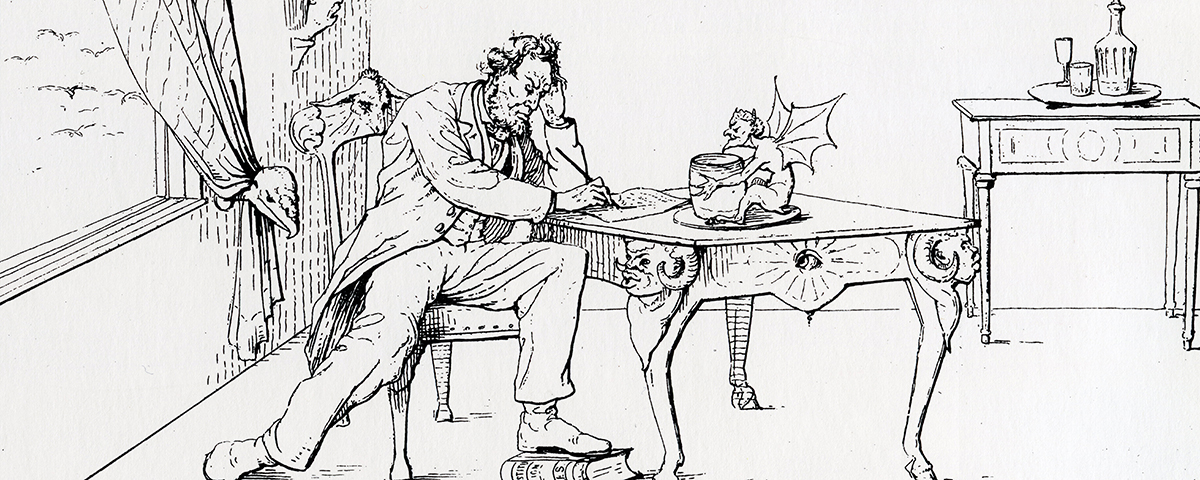

In one of his typical, dialect-rich comic essays, the fictional Ward visits the White House to find a babbling, confused president intent on telling his funny stories and blissfully unaware that they do not make much sense:

I called on Abe. He received me kindly. I handed hum my umbreller, and told him I’d have a check for it if he pleased. That, sed he, puts me in mind of a little story. There was a man out in our parts who was so mean that he took his wife’s coffin out of the back winder for fear he would rub the paint off the doorway. Wall, about this time there was a man in a adjacent town who had a green cotton umbreller.

Did it fit him well? Was it custom made? Was he measured for it?

Measured for what? said Abe.

The umbreller?

Wall, as I was sayin, continued the President, treatin the interruption with apparent contempt, this man sed he’d known that there umbreller ever since it was a parasol. Ha, ha, ha.

Lincoln always insisted he was a retailer, not a wholesaler, of the stories that made him famous. I don’t make the stories mine by telling them, he modestly maintained. But such confessions did not stop publishers from issuing books like Old Abe’s Jokester and The Humors of Old Abe while he was serving in the White House. Lincoln thus became the first president ever to inspire a joke book—poetic justice for a man who listed at least one joke collection among the favorite books of his youth.

Lincoln’s jesting ultimately did him as much harm as good. Writers twitted him with volumes like Abraham Africanus I, a raw satire accusing him of radical policies on race and tyrannical practices such as arbitrary arrests. Cartoonists continued their assaults as well. Some Confederate caricaturists portrayed him as Satan incarnate, hiding behind the avuncular mask of a bearded statesman. And some British artists depicted him disdainfully as a crafty bartender serving the public a mixture of bunkum, bosh, and brag.

The vigor of such attacks only increased as the bitter 1864 election campaign heated to a boil. A riotously funny 1864 campaign biography, Only Authentic Life of Abraham Lincoln, Alias Old Abe, described him with acidic gusto:

Mr. Lincoln stands six feet twelve in his socks, which he changes once every ten days. His anatomy is composed mostly of bones, and when walking he resembles the offspring of a happy marriage between a derrick and a windmill…. His head is shaped something like a ruta-bago, and his complexion is that of a Saratoga trunk. His hands and feet are plenty large enough, and in society he has the air of having too many of them…. He could hardly be called handsome, though he is certainly much better looking since he had the smallpox…. He is 107 years old.

Some of the more vicious presidential campaign cartoons depicted Lincoln as a supporter of miscegenation (the period term for race-mixing), a highly unpopular position at the time. One example showed him happily welcoming a mixed-race couple in a topsy-turvy society in which African Americans ride in carriages liveried by white servants. Such tableaux were meant to stir up a racist electorate by encouraging fears that a biracial society would be inevitable if Lincoln were reelected.

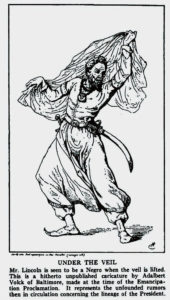

Along the same line of attack, several caricatures hinted that Lincoln had African heritage. One plate by Baltimore etcher Adalbert J. Volck showed the president as an Arabian dancer, veiled to conceal his ethnic features. And in an anonymous 1864 campaign cartoon, he was an actor on stage, portraying Shakespeare’s evil Moor, Othello.

During his reelection campaign, Lincoln became enmeshed in a bizarre comic plot that might have caused considerable political fallout had he not sensed its potential danger. The episode began on September 29, 1864, when the author of the parody volume Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races sent the president a complimentary copy with a letter asking for his endorsement. The author gushed, Permit me to express the hope that, as the first four years of your administration have been distinguished by giving liberty to four millions of human beings, that the next four years may find these freedmen possessed of all the rights of citizenship….

The author’s trap failed to snare Lincoln, who saw through the wily attempt to secure a presidential declaration on racial integration that Democrats could then use to attack the Republicans. This ‘dodge’ will hardly succeed, the London Morning Herald predicted, for Mr. Lincoln is shrewd enough to say nothing on the unsavory subject. The newspaper was correct. The old storyteller had a nose for a practical joke, and proved much too smart to allow this dangerous one to be played on him. Lincoln never replied to the anonymous letter. He simply pasted it into the inside cover of his copy of the Miscegenation book and filed it away without comment. It was found in his papers after his assassination.

The abuse…in newspapers, to quote presidential secretary John Hay, rarely bothered Lincoln. At least once, however, a published item—-a false report—pushed him close to losing his temper. In 1864, the anti-Lincoln New York World falsely reported that during a tour of the hallowed Antietam battlefield, the president had requested a ribald song from his friend Ward Hill Lamon. This makes a feller feel gloomy, the insensitive president was quoted to have said after inspecting the spot where 900 men had fallen. …Can’t you give us something to cheer us up? Give us song, and give us a lively one. Concluded the World: If any Republican holds up his hands in horror, and says this story can’t be true, we sympathize with him from the bottom of our soul; the story can’t be true of any man fit for any office of trust, or even for decent society; but the story is every whit true of Abraham Lincoln, incredible and impossible as it may seem.

Lincoln was deeply pained by the suggestion——designed to sway the soldiers’ vote–that he could have defiled hallowed ground littered with more dead and wounded than had ever fallen in a single day of fighting. He could not have been comforted by a pictorial accompaniment to that libel, a hostile campaign print depicting him clutching a Scotch cap as he stands among the swollen dead and bleeding wounded, urging a horrified companion to sing us ‘Picayune Butler,’ or something else that’s funny.’

It was more than even Lincoln could endure. Still, he resisted his friend Lamon’s repeated calls that he issue a public denial. He refused to dignify the calumny with a response. When he did finally put pen to paper to write out his own version of his visit to Antietam, he quickly instructed Lamon to destroy the result. Perhaps the act of writing down his thoughts was his way of letting off steam.

Lincoln never escaped the bombardment of topical humor. When he won reelection, London Punch portrayed him as a phoenix rising from the ashes of ruined commerce, quashed civil liberties, and trampled states’ rights. Even his legendary love for the theater exposed him to ridicule. In August 1863, Lincoln wrote to thank the celebrated actor James Hackett for a copy of his new book on his favorite stage roles. Lincoln had his own favorites, and his thank-you letter frankly expressed his views, including his judgment that nothing equals Macbeth.

Hackett made the error of publishing Lincoln’s communication as a means of enhancing his own reputation. The result provoked howls of laughter from the press, which mercilessly derided Lincoln for his amateurish taste. A mortified Hackett wrote back to Lincoln to apologize for the efforts by the Newspaper-Presses in publishing your kind, sensible, & unpretending letter…accompanied by satirical abuse.

Lincoln replied to reassure Hackett that the affair had not upset him. Give yourself no uneasiness, he counseled the actor, adding that he was not much shocked by the newspaper comments. His skin had long ago grown thick enough to withstand the satirical abuse fired at him during his 30 years in the political trenches.

As Lincoln touchingly expressed it, the endless taunts were but a fair specimen of what has occurred to me through life…. I have endured a great deal of ridicule without much malice; and have received a great deal of kindness, not quite free from ridicule. I am used to it.

Modern Americans should be used to it, too. American presidents from John Adams to Bill Clinton—Lincoln among them—have been subjected with oppressive regularity to ridicule, both poisoned with malice and not. Most learn to ignore it. If I were to read, much less answer, all the attacks made upon me, Lincoln wrote, this shop might just as well be closed for any business….

America’s first humorist-president became one of its most often parodied presidents as well. But Lincoln apparently had less trouble accepting such taunts than do modern Americans scandalized by the likes of Desmond Pfeiffer; just as he could tell a joke, he could also take one. And he knew that triumph is a target’s best friend. If the end brings me out right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything, he pointed out. If the end brings me out wrong, ten thousand angels swearing I was right wouldn’t make any difference.

Perhaps Lincoln’s optimism stemmed in part from a realization that humorists make a difference. That was true then as well as now. Purveyors of wit can provide a troubled people an occasional laugh in the midst of great tragedy. Besides, Americans who laughed at Lincoln could always be comforted by the fact that the president laughed at himself.

This article was originally published in the February 2001 issue of Civil War Times magazine.