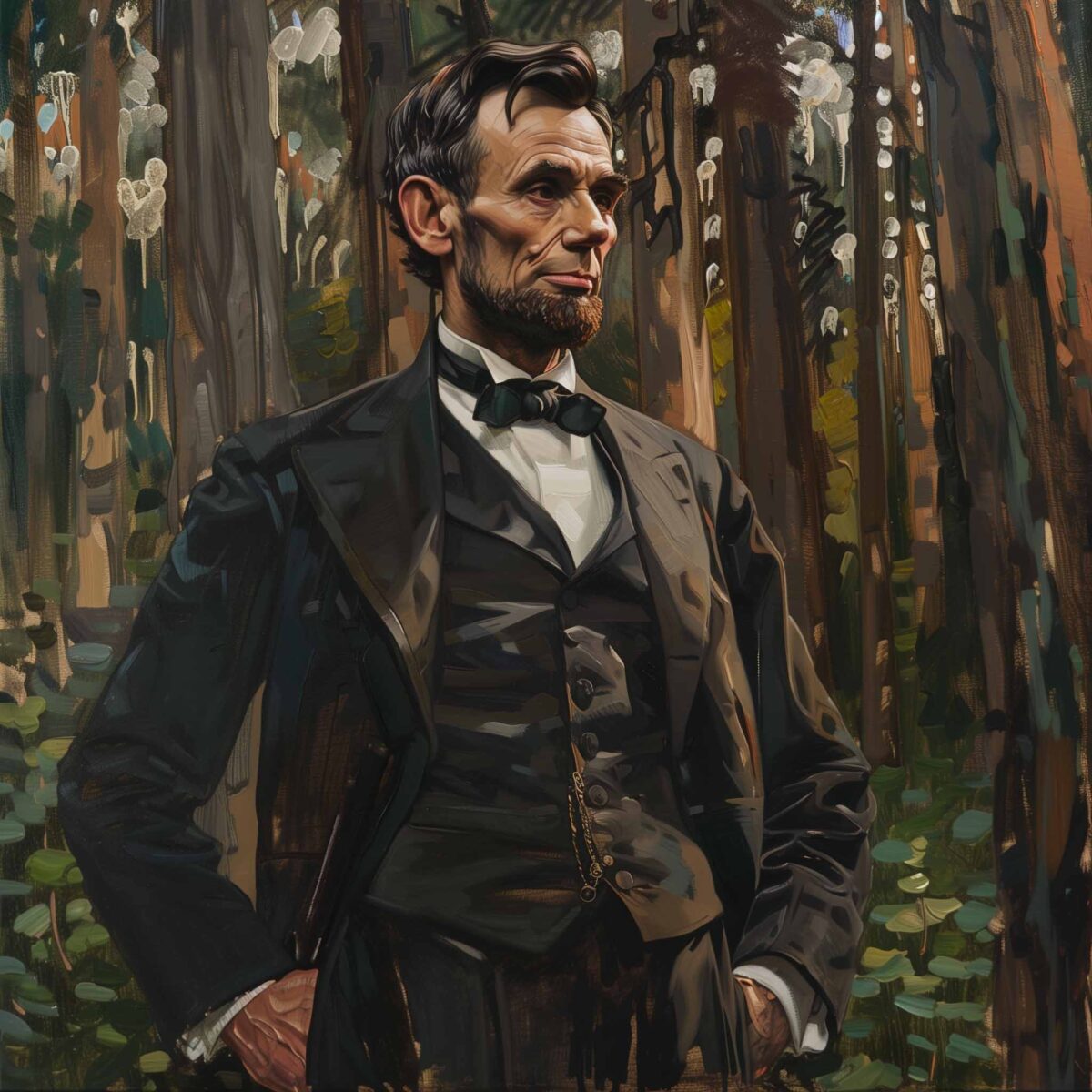

Abraham Lincoln stood atop a hill outside Council Bluffs, Iowa, looking west. The broad Missouri River valley stretched from north to south before him. It was 1859, and this was the place, an acquaintance assured him, from which a transcontinental railroad across the Western expanses ought to originate. The view and that advice turned Lincoln’s thoughts increasingly to the future of the American West.

Born and raised in a region considered the frontier in the early 19th century, Lincoln became intrigued with the peoples and lands beyond the Mississippi. He ultimately envisioned a union extending from sea to shining sea, a hope that broadened his vision beyond goings-on in the established Northern states and increasingly discontented Southern states.

The divisive issue of slavery, often considered an exclusively North-South problem, was also a problem of the West. In fact, in the early 1850s, the political battleground over slavery centered on the frontier. Opposition to the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act in particular boosted Lincoln’s profile and that of the new Republican Party. Later in the decade, Lincoln remained focused on the West as the struggle to decide the slavery question took violent form in “Bleeding Kansas.” For the good of that region, as well as the solidarity of the nation, Lincoln opposed the spread of slavery to the Western territories, a stand that helped propel him into the White House in 1861.

During his presidency, Lincoln drew even closer to the West, which he dared not let fall into Confederate hands. His vision of rails crisscrossing the Great Plains never dimmed, and he supported measures to build tracks to the Pacific. But a transcontinental railroad wouldn’t happen overnight, especially not with civil war raging. Meanwhile, other means of transportation would carry people to the open frontier; all they needed was incentive. The president signed into law the 1862 Homestead Act and also supported legislation to launch regional land-grant colleges for the agricultural and mechanical arts. Lincoln largely deferred the so-called “Indian problem” in the West, though when action was required on a specific problem—namely, the fate of prisoners from the 1862 Sioux Uprising—he did get involved (see sidebar, P. 35). Overlooked in most considerations of Lincoln are that three Western territories were created during his presidency and that he devoted major attention to patronage and political appointments in the West, to the extent he might be dubbed a “Founding Father of the Political West.” He also dealt with military strategies and Reconstruction policies west of the Mississippi. Ideally, as Lincoln saw it, free, hard-working Republicans would dominate the region. Many problems still had to be worked out, but his Western vision was on track at the time of his assassination.

Lincoln is considered a “Man of the West” largely due to his rough-and-tumble, log-cabin upbringing, but the 16th president demonstrated enough peripheral vision while confronting the horrors of civil war in the East to rate as a “President Who Believed in the West.”

The three states in which Lincoln was raised— Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois—were considered part of the West two centuries ago. At the time the label “Man of the West” carried some baggage with it, calling to mind an unpolished backwoodsman with homespun attire and unkempt hair. Indeed, one observer in New Salem, Ill., where Lincoln lived during his 20s, commented that lanky Abraham presented “a rather singular grotesque appearance”; another described him “as ruff [sic] a specimen of humanity as could be found.” Others, though, recorded positive impressions of this plain and upright Western man who worked with his hands as a farmer, flatboatman and laborer. During the May 1860 Republican nominating convention, Lincoln’s cousin John Hanks and a colleague dashed onto the floor with two fence rails they claimed Lincoln had split and an accompanying banner emblazoned, ABRAHAM LINCOLN—THE RAIL CANDIDATE FOR PRESIDENT IN 1860. The crowd broke into a loud cheer, and the “Rail Splitter” candidate was born.

Early in his political career, as a Whig Party member, Lincoln had followed his idol Henry Clay in championing federal- and state-funded highway, canal and railroad projects. His later support for a transcontinental railroad was a natural extension of the belief that internal improvements triggered national growth. That’s not to say Lincoln was in favor of expansion by any means. By contrast, Jacksonian Democrats and Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln’s competitor from Illinois, rode—sometimes even led—the prancing stallion of expansion known as Manifest Destiny that galloped across the country in the 1840s.

In January 1848, as a freshman U.S. Representative from Illinois, Lincoln introduced “spot resolutions” to hold Democratic President James K. Polk responsible for bringing on the Mexican War (1846–48), accusing the president of the “sheerest deception.” Not surprising, the “locos” (Lincoln’s word for his Democratic opponents) accused him of being unpatriotic, and Douglas later painted Lincoln as something of a traitor during their famous 1858 campaign debates. Lincoln reminded their audiences that although he had roundly criticized the president for leading the country into war, he always voted for measures to support the soldiers. He would also support the Whig nominee for president, General Zachary Taylor. The truth was Lincoln opposed Polk’s conduct of the war but not the war itself, and he never spoke out against the territorial gains America secured with its victory.

In 1846, while Congress wrestled over how to resolve the Mexican War, David Wilmot, an obscure congressman from Pennsylvania, introduced a legislative amendment calling for the disallowing of slavery in any territory gained from the conflict. Dubbed the Wilmot Proviso, the amendment failed to pass, but it became the rallying cry for northern Whigs like Lincoln and, later, most members of the new Republican Party. Lincoln’s belief in restricting the spread of slavery would draw his attention westward until his death. In 1849 he nearly became a “Man of the Far West,” showing interest when the Taylor administration offered him the position of territorial governor of Oregon. Though Lincoln later told friends that his wife, Mary, had balked at moving their family to distant Oregon, he likely also realized that his being a Whig would not play well in that Democratic state.

From 1849 to 1854, Lincoln largely rested from his political wars and plied his lawyerly trade. But the West was on his mind again and his political life recharged after Stephen Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. Passed in spring 1854, the act repealed the earlier Missouri Compromise, which for 30 years had prohibited slavery north of Missouri’s southern border. Now Kansas and Nebraska could be organized around the principle of popular sovereignty, allowing white male residents to decide whether or not to permit slavery there. Douglas’ legislation undercut Lincoln’s stance on the Wilmot Proviso.

Quiet at first, Lincoln exploded to the fore of the “anti-Nebraska men” by that fall. In October at Peoria, Ill., in one of his most powerful speeches, Lincoln for the first time denounced slavery as a moral evil. He ridiculed Douglas’ contention that slavery, by nature, would never expand into Kansas and Nebraska as “lullaby” thinking. The speech was a ringing Lincoln declaration, denouncing the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in the Kansas-Nebraska Act and pointing to the struggles that lay ahead in keeping those territories free.

His fears soon proved well founded, as a vicious border war erupted in eastern Kansas— 400 miles west of Lincoln’s Springfield—between invading Missouri “Border Ruffians” and Free-State Kansans. The latter were importing the latest rifles, which they referred to tongue-in-cheek as “Beecher’s Bibles,” after famed abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher. From November 1855 into 1858, “Bleeding Kansas” was in chaos. In 1857 a rigged legislature met in Lecompton and sent a proslavery constitution to Congress. The Buchanan administration accepted the constitution, but Congress, under the feisty leadership of Stephen Douglas, rejected it. In denouncing the document and breaking with President James Buchanan, Douglas opened a breech in the Democratic Party, a widening chasm that separated the Democrats into Northern and Southern factions in 1860 and boded ill for the party’s future.

When Lincoln contested Douglas’ senatorial seat in 1858, Western and slavery issues formed the heart of their thunderous debates. In that oratorical contest of nearly 200 speeches, but especially during the seven famous debates of three hours each, the two Illinois politicians vigorously jousted on two core issues: the morality of slavery and whether it should be extended into the Western territories. Lincoln denounced slavery and attacked the pragmatic weaknesses of Douglas’ positions. On one occasion Lincoln declared Douglas’ “squatter sovereignty” so watered down it had become “as thin as homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death.” Regardless, in 1858 state legislatures still selected U.S. senators, and with an unbalanced apportionment in their favor, the majority Democrats reelected Douglas.

Lincoln had lost his second Senate bid, but his performance against Douglas had persuaded Republicans to consider him as a viable presidential candidate in 1860. Accepting their nod, Lincoln began to travel widely and deliver more speeches. In 1859 he made two trips across the Mississippi. A nine-day journey in August took him to Iowa, where he spoke at Council Bluffs and discussed with engineer Grenville Dodge the best routes west for a transcontinental railroad. Lincoln’s second trip, also for nine days, took him through Missouri into Kansas Territory. At a speech in Southern-leaning Atchison, Lincoln declared that any attempt at secession would be considered treason, adding forcefully, “If they attempt to put their threats into execution, we will hang them as they have hanged old John Brown today.” But the future president also knew how to cajole his fellow Westerners. He drew laughter when he singled out from the audience one of the territory’s leading citizens, former Missouri Attorney General Benjamin Stringfellow, who had declared that Kansas could never be a free state because “no white man could break prairie.” If that were true, Lincoln joked, then he himself must be black, for he had broken prairie many times. The onetime pioneer’s ability to swap yarns with free-soil and proslavery Kansans alike helped solidify a Republican base in Kansas Territory and ensure it entered the Union as a free state.

In the campaign run-up, Lincoln solidified his links to the West, earning his “Rail Splitter” moniker during the state and national Republican nomination conventions, both in Illinois in May 1860. Among other reforms, his platform called for regional improvements and a railroad to the Pacific. Lincoln won with 39.9 percent of the vote to Douglas’ 29.5 percent.

Amid the melee of a nearly all-encompassing civil war, the 37th Congress still found time to pass a clutch of bills of central importance to the American West. Although Lincoln did not guide the passage of legislation toward a transcontinental railroad, a homestead act, a college land-grant act and the Department of Agriculture, all aligned with his Western vision.

Lincoln naturally and easily swung his support behind the building of a transcontinental railroad. He’d had a longtime love affair with the rails. In 1859 he reportedly told Grenville Dodge, “There is nothing more important before the nation at this time than the building of a railroad to the Pacific Coast.” (As chief engineer, Dodge would help construct the first transcontinental railroad after Lincoln was dead.) So influential was Lincoln’s support for the massive engineering project that one wag concluded, “Abraham’s faith moved mountains.”

When Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act in June 1862, Lincoln immediately signed it. He also enthusiastically supported the huge land grants and financial aid given to the railroad construction company. When that act failed to attract sufficient investment, Lincoln backed Congress and initiated another act in July 1864, doubling the land grants and expanding the financing. As chief magistrate, the president claimed the privilege of determining the railroad’s Eastern and Western terminuses and deciding on the gauge (width) of its rails.

Lincoln wanted the transcontinental railroad to bring together the East and West coasts. Binding California to the East and keeping it in the Union were foremost on the embattled president’s mind. He also appreciated the benefit of expanded federal access to Western mineral wealth, as well as the economic possibilities that would come from opening up the Great Plains and Far West to settlement.

Three important pieces of congressional legislation forever link agriculture, Lincoln and the American West. The most significant—widely considered the most important land policy measure ever enacted in the U.S. Congress— was the Homestead Act of 1862. This groundbreaking legislation provided 160 acres of land virtually free to bona fide homesteaders after five years of residence (“proving up”). Lincoln and most Republicans favored the legislation, convinced that free land, like a powerful magnet, would draw ambitious homesteaders west, expand the nation’s economy and, not least, bring farmers into the Republican ranks.

Lincoln also called for establishment of a Department of Agriculture, a research bureau that would gather statistics and provide an annual farming report. Lawmakers readily followed up on his suggestion, and Lincoln praised the department’s efforts in his December 1862 annual message to Congress.

The third measure was the Morrill Land-Grant College Act. It provided each state with 30,000 acres of federally owned land per senator and representative for the establishment of a college (or colleges) “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts.” Ironically, several Western congressmen unsuccessfully opposed the act, fearing that Easterners would gobble up Western lands to fulfill the grant stipulations. Lincoln signed it into law on July 2, 1862.

The most time-consuming and far-reaching of Lincoln’s Western responsibilities lay in the field of politics. The Constitution mandated that the president or Congress appoint officials in newly formed Western territories. Presidents had done most of the appointing. Lincoln enjoyed providing friends and acquaintances with positions, but such office seekers’ demands proved endless. They gathered around Lincoln like hordes of hungry ants in search of tasty morsels.

When Lincoln began his presidency on March 4, 1861, only nine states stood west of the Mississippi: Louisiana (1812), Missouri (1821), Arkansas (1836), Texas (1845), Iowa (1846), California (1850), Minnesota (1858), Oregon (1859) and Kansas (January 1861). Louisiana and Texas had seceded by Lincoln’s inauguration; Arkansas would two months later. Colorado, Dakota and Nevada all became territories in 1861 just before Lincoln assumed office. During his four years in the White House, Nevada became a state, and Arizona, Idaho and Montana were organized as new territories. As president, then, Lincoln was tasked with appointing officials in 11 Western territories, as well as several states. These appointments allowed the ambitious resident of the White House to expand the power of the Republican Party westward and shape early political trends in the region.

Most of Lincoln’s appointees were former Whigs or new Republicans. Many were political acquaintances or lawyer friends from Illinois, some were politicians Lincoln had met elsewhere, and still others were friends of cabinet members or of leading congressional Republicans. Some served well as Lincoln’s political missionaries in the West, some wobbled indecisively in their unfamiliar surroundings, and some were first-rate rascals, failing to show up or even running off with government funds. Altogether between 1861 and 1865, Lincoln appointed more than 200 men to Western positions—governors, secretaries, judges, Indian agents, surveyors-general, postmasters, etc. His vision of the West was coming together, even as the Civil War raged and the transcontinental railroad remained in the planning stages.

Two states in particular, Missouri and Oregon, best illustrate Lincoln’s political and personal contacts in the West. Such political connections, troubling and vexing as they were, defined his links with Missouri. Indeed Lincoln’s dealings with that disruptive state were unlike those with any other Western entity. Right through the closing months of his presidency, Lincoln remained troubled by the inescapable political, military and legal chaos in Missouri. Riven by conflicts between Union and Confederate diehards and convulsed by more military engagements than any other state save Virginia, Missouri boiled over with all the major issues that led to and festered during the Civil War. Even Conservatives (“softs”) and Radicals (“hards”) within the Republican Party engaged in bitter feuds. Into this bubbling caldron of discontent fell Abraham Lincoln.

The president’s links with Oregon were more personal and far less controversial. Four of his close friends from Illinois had moved to Oregon: David Logan (son of his law partner), Anson G. Henry (his doctor), Simeon Francis (his chief Whig editor) and Edward D. Baker (his closest political friend). This quartet became Lincoln’s political eyes and ears on the West Coast. Logan and Francis, for instance, championed his presidential ambitions. More rabidly political, Dr. Henry served, one author has written, as Lincoln’s “junkyard dog.” Henry’s penchant for pugnacity quickly surfaced, and he barked—even snarled—at Lincoln’s opponents.

Edward D. Baker was the most influential nationally of the president’s Oregon circle. Closely connected to the Lincoln family (Abraham and Mary named their second son Edward [Eddie] after him), Baker had served as a U.S. representative from Illinois before moving to California and then to Oregon in the winter of 1859–60. Supported by the popular sovereignty Democrats, Baker won a U.S. Senate seat in 1860. He was the first West Coast Republican elected to Congress. Baker signaled his closeness to Lincoln by introducing the new president at Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861.

Lincoln’s bonds with Western territories differed from his links with Western states. In such areas as Idaho, Montana, Dakota and Arizona he established territorial governments by naming their chief leaders. He did much the same in existing or new territories like Washington, Nebraska, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico. In some areas he relied heavily on the advice of political friends like Henry and Baker for patronage appointments in Washington, Idaho, Montana and the states of Oregon and California. He also broke precedent by naming Dr. Henry Connelly, a Democrat, governor of territorial New Mexico because he feared a Confederate invasion of that area and thought New Mexico resident Connelly could unite New Mexicans better than a newcomer named from the outside.

The results of Lincoln’s political appointments were mixed. Governors Connelly of New Mexico, James Nye of Nevada and William Henson Wallace of Washington and later Idaho served well. But Governors Caleb Lyon of Idaho and William Gilpin of Colorado, as well as dozens of nominees to the Office of Indian Affairs, were inefficient leaders, political hacks or downright crooks. Jealous territorial residents not selected referred to Lincoln’s appointees as carpetbaggers, importations or, in the case of one official, “another drunkard from Illinois.”

These manifold political connections demonstrate how deeply involved Lincoln was in Western politics. Indeed, such ties represented his most important direct links with the West. That “Founding Father of the Political West” label sticks when one considers his connections. In the six new territories that formed between February 28, 1861 and May 26, 1864, Lincoln saw to it Republicans would do most of the governing.

On June 19, 1862, Congress passed and Lincoln signed a measure outlawing slavery in U.S. territories, all of which lay in the West. A month later Congress enacted the Second Confiscation Act, legislatively freeing Confederate slaves. Lincoln was decidedly lukewarm about the act, as he believed Congress lacked the constitutional right to end slavery in a state. Rather than veto the measure and anger the largely Republican Congress, Lincoln charted his own course toward ending slavery: the Emancipation Proclamation. The preliminary order in September 1862 and the official proclamation on January 1, 1863, ended slavery “within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States.” Lincoln specifically named Arkansas, Texas and parts of Louisiana. Shortly thereafter he began pushing for a constitutional amendment to end slavery in the United States.

A few months into the Civil War, Lincoln began to formulate what roles the trans-Mississippi West should play in the war. First and foremost, he sought to safeguard valuable Western mineral resources and strategic California seaports. He hoped to divide Confederate control at the Mississippi, thereby isolating the pro-slavery bastions of Texas, Arkansas and parts of Louisiana. He also vowed to control the Mississippi River, keeping it open for trade and troop movements as far north as Illinois. Finally, he wanted to ensure the two new states of the Far West, California and Oregon, stayed with the Union.

Some hopes came to fruition. Union forces blocked a Southern invasion of New Mexico Territory at the March 1862 Battle of Glorieta Pass, forcing Texan invaders to abandon most of New Mexico and Arizona and give up their designs on gold-rich Colorado Territory. General Ulysses S. Grant’s ambitious plan to take Vicksburg and clear the Mississippi also worked out, despite Lincoln’s grave doubts about that risky action. Lincoln also supported Union military suppression of the 1862 Sioux Uprising in Minnesota.

But Lincoln’s other Western military ventures led to mixed results or flat failures. He was never able to solve the political-military quagmire in troublesome Missouri, and though he had hoped to drive all Confederates from Texas and Louisiana, Union troops were unable to do so. And Lincoln was greatly upset when trigger-happy volunteers carried out the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado Territory on November 29, 1864. In the end, Lincoln was too weighted down with other crises to pay sufficient attention to military planning in the West.

On the evening of April 11, 1865, two days after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Lincoln appeared at a window over the front door of the White House to give a speech. He discussed in part the readmission of Louisiana, repeating what he had earlier advocated for that state and Arkansas: The Union had had a great fall, and now Lincoln wanted to put it back together again with a lenient policy of Reconstruction. Using these two Western states as testing grounds, Lincoln had stipulated that when 10 percent of a state’s qualified voters in the election of 1860 took an oath of loyalty to the Union, rewrote their constitution and disavowed slavery, they would be readmitted to the Union. Radical Republicans in Congress defeated Lincoln’s “10 percent plan” of Reconstruction, then he pocket-vetoed their much more stringent Wade-Davis Bill. With Reconstruction at a standstill, Lincoln promised his audience that April evening future progress toward reconciliation. Those words and subsequent actions never came. Three days later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln in his state box at Ford’s Theatre.

Abraham Lincoln was labeled a “Man of the West” because he was born on February 12, 1809, in Kentucky’s Hardin County and raised on what was then considered the frontier. But his connections with the trans-Mississippi West were clearly quite substantial and have been largely overlooked. Lincoln had long opposed the expansion of slavery into Western territories. As president he supported a transcontinental railroad, homestead legislation and land-grant colleges; helped organize vast areas of the West into territories; and planted his Republican Party in the region. At the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth, we rightfully celebrate the legacy of a president whose most enduring achievement was the Emancipation Proclamation. But it is important to recognize that his legacy of freedom, opportunity and nationalism extends across the continent. For Lincoln, a strong union meant the North, the South…and the West.

Richard W. Etulain is professor emeritus of history at the University of New Mexico. He is the author or editor of more than 40 books, including Beyond the Missouri: The Story of the American West (2006). This article draws on his forthcoming book, Lincoln Looks West: From the Mississippi to the Pacific. Also suggested for further reading: The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (nine volumes, 1953–55), edited by Roy P. Basler, et al.

Originally published in the April 2009 issue of Wild West.