Thomas James Smith, better known as “Bear River Tom” Smith, is remembered primarily for having preceded the legendary Wild Bill Hickok as marshal of Abilene, Kan. Smith’s stint in office ran just shy of five months, from June 4 to Nov. 2, 1870. He preferred to use his fists rather than guns to keep order in the raucous cow town, right up until that fall day he was mortally wounded and then nearly decapitated with an ax in the line of duty. While his early life is sketchy on specifics, a 1905 letter to former Abilene Mayor Theodore C. Henry from town constable John Conkie detailed the five lively years Smith spent before becoming marshal. Published in the Nov. 29, 1905, edition of the Abilene Weekly Chronicle, the letter corrects lingering misconceptions about Smith.

While the 1870 U.S. Census records Smith’s age as 40, suggesting he was born in 1830, Conkie wrote that Tom was actually born around 1845 in New York City. Smith was not in Abilene when the census was taken, thus the information about him was likely supplied by the Jacob Ludi family, on whose farm he lived. Conkie met Smith in late 1865 when the pair formed a mining partnership near Deer Lodge, Montana Territory. That winter they were snowed in and passed the time swapping life stories.

Smith, wrote Conkie, was of “Irish and Scotch stock,” had a “rather limited” education and loved music, spending countless hours practicing Irish and Scottish tunes on his banjo. When spring arrived, the partners worked the diggings and made a little money before selling their claims and moving to Salt Lake City to overwinter. In the spring of 1867 the pair tried their luck in Idaho Territory, only to return to Salt Lake City that fall after a so-so season of prospecting. In 1868 the partners ventured to the diggings near South Pass, in what that July 25 would become Wyoming Territory, but that trip also proved unsuccessful.

Describing the conditions at South Pass, Conkie noted there was no way of controlling the “rough element” other than with vigilance committees. The camp was plagued by a number of robberies and murders, and the mine owners suspected a man who disappeared about the time one particularly rich miner had been robbed and nearly murdered. At a subsequent miners’ meeting the owners offered a substantial “dead or alive” reward for the delivery of the suspect.

That evening after supper Smith, resolving to bring in the criminal, cleaned and loaded his Henry rifle. The subsequent manhunt was his first such venture, and his only authority was the resolution passed at the miners’ meeting. He was successful, bringing the man into camp the next day, for which he earned both the reward and a good reputation.

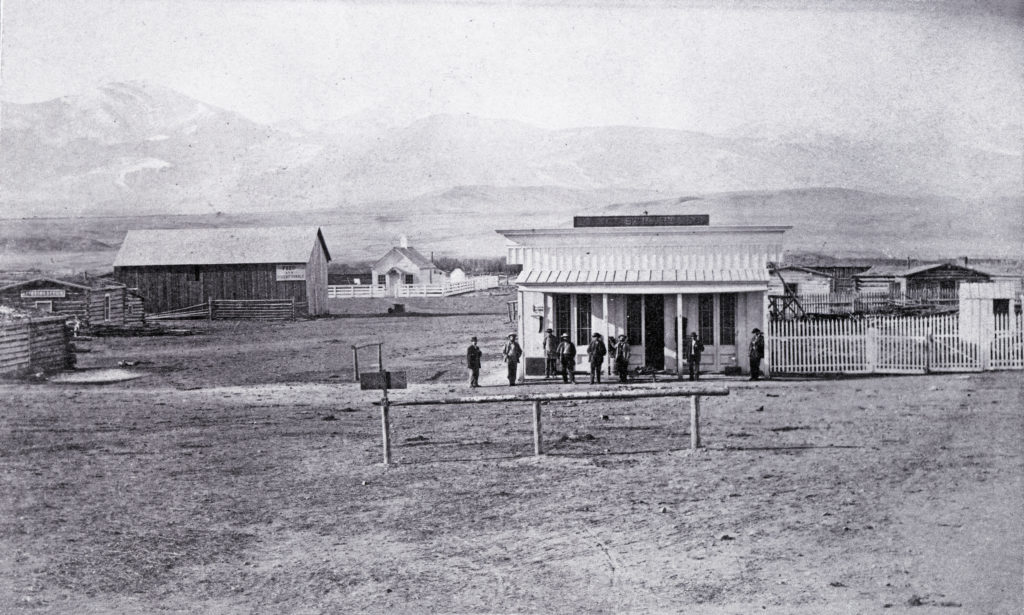

A month later the partners traveled some 65 miles southwest to Green River City (present-day Green River, Wyo.), at the mouth of Bitter Creek, where the line of the Union Pacific Railroad was being surveyed. The newspaper that would become Smith’s nemesis, The Frontier Index, and its overtly racist publisher Legh Freeman, arrived around the same time. The Index came to be called the “Press on Wheels,” as Freeman followed the railroad, publishing the paper in a handful of end-of-track towns in southern Wyoming Territory.

“Tom’s reputation followed him,” Conkie recalled, “and he was appointed marshal.” In fact, on August 6 Smith was elected marshal of Green River City. Assisting him were several officers, including Conkie as a deputy and jailer. Smith did his share of rounding up rowdies, making about half his arrests during one two-week period. As marshal he was also responsible for such mundane duties as collecting property taxes.

While Smith at first allied himself with publisher Freeman in thoughts on what the Democratic Party should be, a falling out between the pair was on the horizon. One particularly nasty accusation against Smith in The Frontier Index involved a “Judge Lacy” of Omaha who one night hurrahed the town after having overindulged in “bourbon cocktails from Pendleton’s.” Freeman alleged that for $50 the “chief of police” had turned a blind eye to Lacy’s shenanigans. The publisher also chided Smith in print for an unpaid city printing debt.

A faction of the Democratic Party nominated Smith for the office of Sweetwater Countysheriff in the election of October 13. His popularity in Green River was obvious, as he outpolled H.K. Tompkins among its citizens 294 to 179. But the marshal failed to carry the rest of the county and lost the election. The results, reported The Frontier Index, sparked a violent exchange between Smith and local attorney James Madison Thurmond:

“Shooting Affray — At half past 3 this afternoon some words in regard to the election today passed between J.M. Thurmond and Thos. J. Smith, resulting in a resort to knives and pistols. Deputy Sheriff Ed. Gillman knocked Smith’s pistol up, and it was discharged in the air.”

Smith and Conkie moved on almost immediately to Bear River City, Wyoming Territory, where crews were grading the railroad. “Tom was not successful in getting an appointment as marshal at this town,” Smith’s partner recalled, and contemporary news accounts bear that out.

Conkie landed a contract to haul ties from Piedmont to the Union Pacific right of way, while Smith remained in Bear River City. Conkie suggested his partner come to Piedmont, but “[Tom] was drinking and would not come.” Conkie made no mention of Smith’s means of making a living in Bear River City, but he likely worked on the railroad grading crew.

In his 1905 letter Conkie noted The Frontier Index continued to pen “uncomplimentary editorials” about Smith, which finally prompted Tom and a reported 200 followers to raid the newspaper office in Bear River City on November 19, touching off what came to be known as the Bear River Riot. According to the November 23 edition of Salt Lake City’s Deseret Evening News, the disparaging editorials were in regard to Smith’s stint as Green River marshal.

The article also recounts other events leading to the riot:

“Mr. [Chance L.] Harris, one of the editors of the Frontier Index, called this morning and related to us the origin of the recent riot at…[Bear] River. He says it originated through the occasional arrest and imprisonment, for drunkenness, of some of the graders, which infuriated their fellow workmen, who determined to release them…and in addition to this the proprietors of the Index had pressed Tom Smith, one of the leaders of the mob at Bear River, but formerly city marshal at Green River, for $70, which he owed them for printing done for the city while at Green River.”

The Index office was the first building attacked by the angry mob, according to the November 27 edition of the Virginia City–based Montana Post. On that same date The Border Sentinel, published in Mound City, Kan., provided more details, reprinting a November 20 dispatch to the Missouri Democrat from that paper’s correspondent in Bear

River. The mob, according to the dispatch, had set torch to the Index office by 8 a.m. on November 19 and the jail by 1 p.m. The reason its correspondent gave for the riot was the vigilante lynching of “three roughs, November 11th, by the citizens,” an act wholly supported by Freeman in the Index. A follow-up dispatch a day lateridentified the ringleaders of the riot as men named “Smith and Dailey, [who] were seriously wounded and are not expected to live.”

By nightfall on the 20th the disturbance had quieted down as troops from Fort Bridger approached and the rioters retreated to the mountains. In its wake military authorities arrested Smith and sent him to the penitentiary in Salt Lake City for some weeks, though according to Conkie, Smith was ultimately released, perhaps after having awaited charges that never came.

Soon thereafter Conkie left Piedmont for Cheyenne, where he opened a restaurant and bowling alley. Smith soon joined him and remained in Cheyenne about six months. From there “Bear River Tom”—as he’d been dubbed after having led the uprising against that town’s vigilantes—went to Denver and then Kit Carson, Colorado Territory, where he was hired as an officer under Town Constable Pat Desmond. Smith served well there, and Theodore Henry, the first mayor of Abilene, heard good things about him.

Cleaning Up Abilene

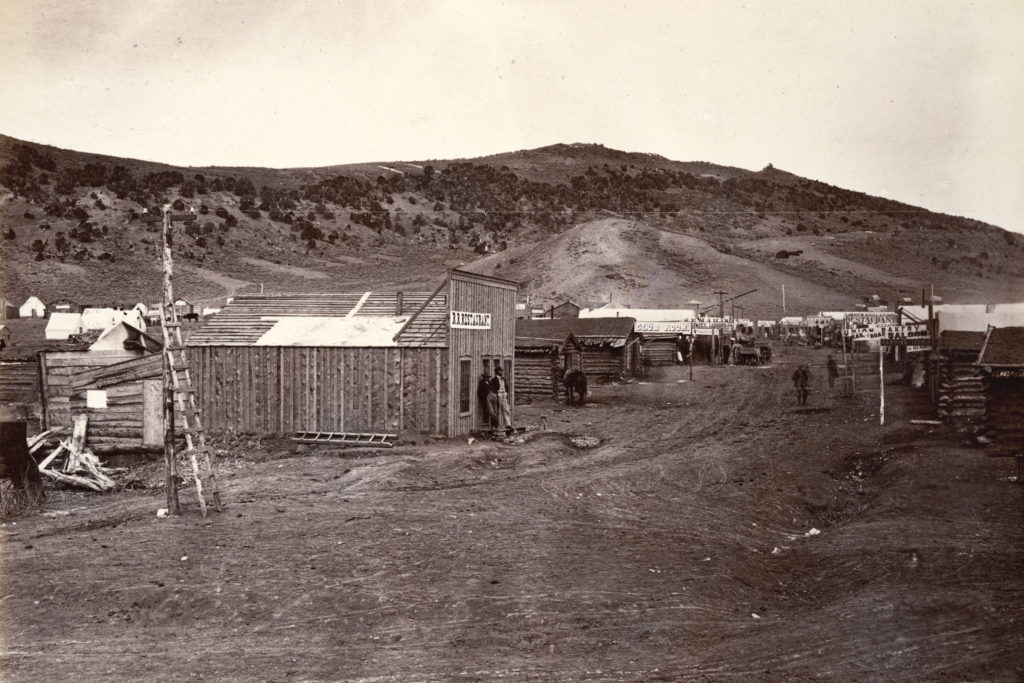

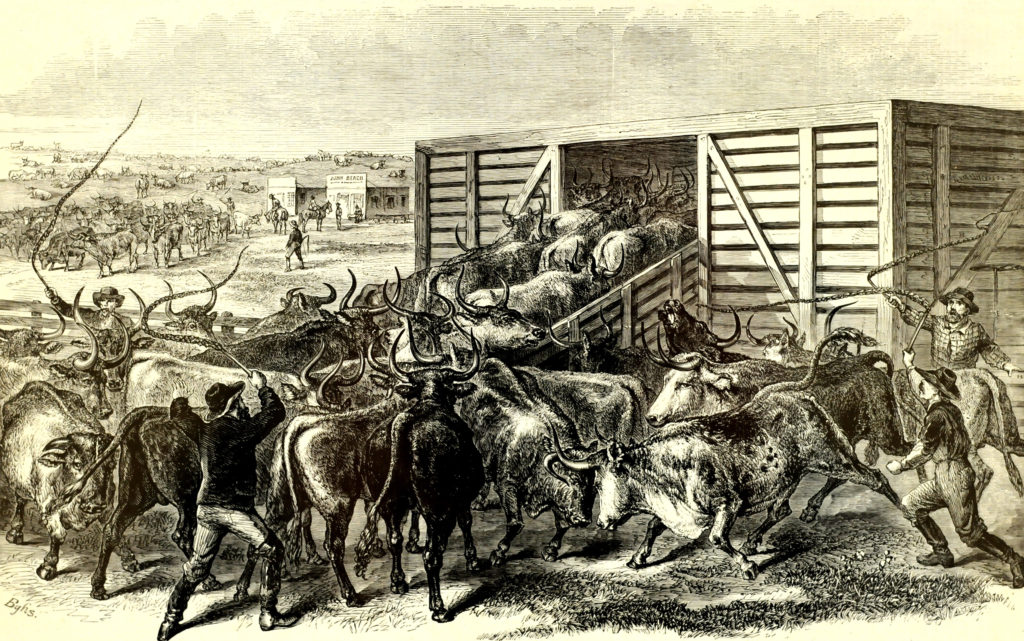

Henry recalled his Kansas town as “the most famed and godless little city on this continent.” In Abilene’s early days Texas cowboys had nearly full reign during the cattle drive season. One drunken evening they tore down the walls of the nearly completed stone jail. After it was rebuilt, cowboys again raided the jail, pulling the bars from a cell to release one of their own who’d been hurrahing the town. Cal Bascom, who worked for the Union Pacific at Abilene and such other wild towns along the line as Ellsworth and Hays, described Abilene as “wild and woolly and hard to curry, filled with cowmen, gamblers, disorderly women and all around toughs.”

Realizing they had to restore some degree of order, town officials on May 2, 1870, enacted ordinances pertaining to the carrying of firearms, the operation of saloons and bordellos, gambling, the establishment of a police force and related matters that were to go into effect on May 20. The ordinances were only enforced in the most severe cases, however, owing to the economic necessity of retaining the cattle trade.

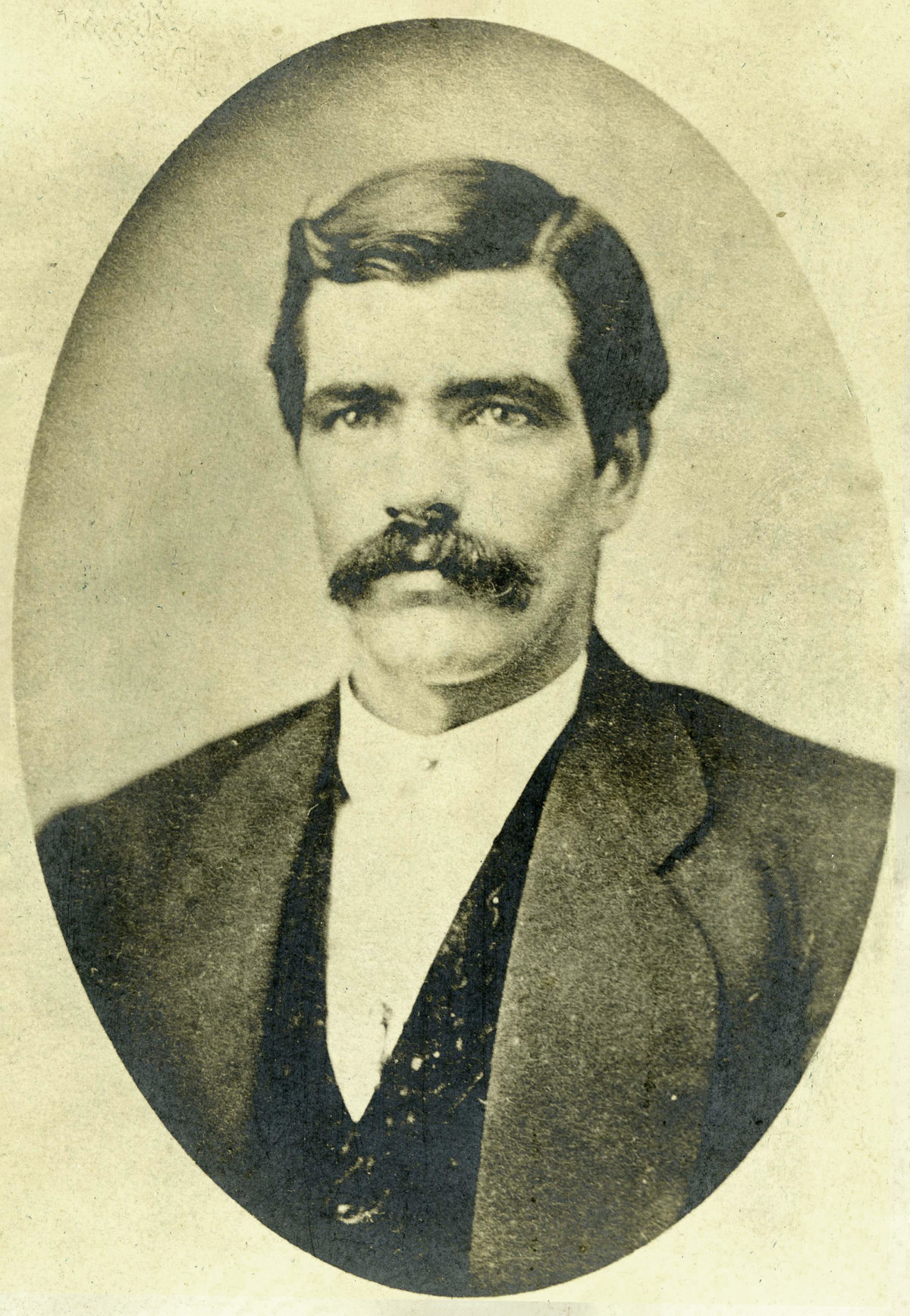

The town fathers also began fishing about for a city marshal who could stand up to the Texas rowdies whenever they hit town. Among the first applicants they considered was Smith. Years later Henry recalled him as a broad-shouldered, gentle-mannered man standing 5 feet 11 inches and weighing 170 pounds, with auburn hair, a light mustache and gray eyes of a bluish tint. According to the mayor, Smith had come directly east from Kit Carson, Colorado Territory, and had a good reference from a reputable citizen of Abilene. But bullheaded Henry and the other town fathers instead hired a series of incompetent local men, followed by big city “professionals.” Henry recalled:

“Successive marshals were tried, failed and in turn resigned. The chief of police of St. Louis was implored to send us a couple of men competent to come and run the town for us. In a few days they appeared, vouched for, to fill our order. Their identity and mission were soon known over town. Every device lawless deviltry could contrive was let loose that day. The brace of ‘tenderfeet’ without tendering their farewell compliments, took the return midnight train for Missouri!”

On a Saturday in late May 1870 Mayor Henry finally wired Smith, asking him to reapply for the marshal position. On June 4 the City Council formally hired Bear River Tom at the very respectable sum of $150 per month. Smith immediately made his presence known. Daniel R. Wagstaff, the sheriff of neighboring Saline County in 1870, witnessed an incident that may be the basis for the well-known stories of Smith’s thrashing of “Big Hank” and buffaloing of “Wyoming Frank.”

Soon after Smith had been sworn in as marshal, Wagstaff arrived in Abilene to attend a judicial meeting. The two of them had just walked into a saloon when Smith was accosted by a “big, husky cowboy.” The cowboy asked whether the marshal was “the great Tom Smith who claims to be such a fighter,” to which Smith replied, “I’m your huckleberry.” The cowboy shot back that he considered Smith little more than a blowhard. Spying a pistol on the cowboy’s hip, Smith told him it was against the law to carry a firearm in Abilene. “Oh, I’ll carry a gun if I want to,” the cowboy replied dismissively. Wagstaff noted the abrupt end to the encounter:

Tom simply grabbed that fellow by the shoulders and throat and laid him on his back, put his foot on the cowpuncher’s throat, took his gun away, searched him, slapped his face and gave him 10 minutes to leave town. That’s the way Tom Smith got along with the unruly punchers. He didn’t arrest half of them, although he could have had he wanted to.

In addition to his town marshaling duties Smith served as a deputy U.S. marshal and was hired as undersheriff by Dickinson County Sheriff J.A. Cramer. Given Cramer’s ill health, Smith assumed many of the sheriff’s duties in Cramer’s absence.

In September 1870 Undersheriff Smith was paid $335.95 for services in the capture of Charles R. “Buckskin Bill” Phillips. Weeks earlier The Abilene Chronicle had reported Philips was wanted for having stolen 10 horses and one mule. Smith and an unnamed assistant set out in pursuit, trailing Phillips 50 miles northwest toward Concordia, Kan. They arrived in Concordia on July 25, only to learn that five days earlier the rustler, who had since shed the mule, had passed within 5 miles of town. From there Phillips had veered east, stopping at Pawnee City, Neb., to dispose of several horses before continuing to his home near Brownville, Neb. It was there Smith caught up with him. On July 28 the intrepid lawman had Judge Alfred W.Morgan issue a warrant for Phillips’ arrest. He then handed the warrant to Nemeha County Deputy Sheriff Hugh Baker, who made the arrest, lodging Phillips in the Brownville jail. Smith then turned for home. En route he stopped in Concordia on August 1 and updated the Concordia Empire on the disposition of the stolen stock. “Bill [Phillips] had sold some of the stock at Pawnee City,” Smith told the paper, “and they [town toughs] attempted to prevent him [Smith] from getting the property by telling him he had better get out, or he soon would have nothing to go out on.…The sheriff captured nearly all the stock.”

Deputy Sheriff Smith next turned his attention to a notorious shanty town northwest of Abilene’s city limits. The Sept. 8, 1870, edition of the Abilene Weekly Chronicle reported on his closure of the brothels there:

“Cleaned Out — For some time past a set of prostitutes have occupied several shanties about a mile northwest of town. On last Monday or Tuesday [September 5 or 6] Deputy Sheriff Smith served a notice on the vile characters, ordering them to close their dens—or suffer the consequences. They were convinced beyond all question that an outraged community would no longer tolerate their vile business, and on yesterday, Wednesday, morning the crew took the cars for Baxter Springs and Wichita. We are told that there is not a house of ill fame in Abilene or vicinity.…Chief of Police T.J. Smith and his assistants and [Police Magistrate] C.C. Kuney Esq. deserve the thanks of the people for the faithful and prompt manner in which they have discharged their official duties. A grateful community will not forget the services of such efficient officers.”

Tragic End

Alas, only five months after being hired to clean up Abilene, Smith was slain in the line of duty. He was killed on Nov. 2, 1870, while attempting to arrest farmer Andrew McConnell for the murder of neighboring rancher John Shea.

On October 23 McConnell had shot Shea through the heart during a heated argument reportedly after having caught the rancher driving cattle across McConnell’s land. After the shooting McConnell summoned a doctor and turned himself in to authorities. At a preliminary examination before Dickinson County Deputy Sheriff Andrew S. Davidson neighbor Moses Miles testified McConnell had acted in self-defense, and authorities released the latter from custody. However, other neighbors soon came forward with information suggesting Miles had lied on McConnell’s behalf, and authorities issued a warrant for McConnell’s arrest.

On November 2 Smith and Deputy James H. McDonald rode out to McConnell’s dugout, where they encountered the farmer and neighbor Miles. When Smith informed the pair he was a deputy sheriff with a warrant to arrest McConnell, the farmer abruptly shot the sheriff through the right lung. Smith returned fire, wounding McConnell. Then the two wounded men began to grapple. Smith had gotten the upper hand when Miles intervened and clubbed Smith with a gun. Finally, taking up an ax, Miles nearly severed the lawman’s head from his body.

Outnumbered and undoubtedly horrified, Deputy McDonald rode back to Abilene and gathered a posse. On reaching McConnell’s dugout, they found Smith’s body, but McConnell and Miles had fled. Three days later, near Clay Center, Kan., a posse captured the fugitives, who were charged with Smith’s murder. Tried and convicted in March 1871 at trial in Manhattan, Kan., they were sent to Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing, McConnell for a 12-year sentence, Miles for 16 years.

Smith was laid to rest in the Abilene Cemetery on Nov. 4, 1870. The day prior the Weekly Chronicle published a tribute to the tough-as-nails lawman:

“He came to this place last spring, when lawlessness was controlling the town…and soon order and quiet took the place of the wild shouts and pistol shots of ruffians who for two years had kept orderly citizens in dread for their lives. Abilene owes a debt of gratitude to the memory of Thomas James Smith, which can never be paid.”

On Memorial Day, May 30, 1904, the citizens of Abilene made a down payment on that debt of gratitude by reinterring Smith’s remains in a place of prominence in the cemetery and capping his memorial with a bronze plaque dedicated to “a fearless hero of frontier days, who in cowboy chaos established the supremacy of law.”

For further reading on the topic author Roger Myers recommends Why the West Was Wild, by Nyle H. Miller and Joseph W. Snell; Ballots and Bullets: The Bloody County Seat Wars of Kansas, by Robert K. DeArment; and Dodge City: Up Through a Century in Story and Pictures, by Fredric R. Young.