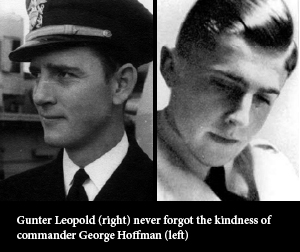

On March 19, 1944, Allied warplanes blew up a German U-boat off the coast of the Cape Verde Islands, killing 47 of its 55 crewmen. Among the survivors was the submarine’s Austrian commander, Gunter Leopold, who was picked up by the destroyer USS Corry. Leopold was immediately surprised by the generosity of the American crew, prompting a friendship with the Corry’s commander, George Hoffman. When Hoffman passed away more than 47 years later, Leopold wrote to his widow to reminisce about their unlikely friendship. (The letter’s minor errors are the result of Leopold’s attempt to write in English, which he understood but did not speak fluently.)

On March 19, 1944, Allied warplanes blew up a German U-boat off the coast of the Cape Verde Islands, killing 47 of its 55 crewmen. Among the survivors was the submarine’s Austrian commander, Gunter Leopold, who was picked up by the destroyer USS Corry. Leopold was immediately surprised by the generosity of the American crew, prompting a friendship with the Corry’s commander, George Hoffman. When Hoffman passed away more than 47 years later, Leopold wrote to his widow to reminisce about their unlikely friendship. (The letter’s minor errors are the result of Leopold’s attempt to write in English, which he understood but did not speak fluently.)

January 2, 1992

Dear Lois,

The new year 1992 was not yet one and a half hours old when William Dutton called to inform us that George had died. Although I was aware of the fact that George had been a very sick man owing to his lung problems, I was shattered by the news of his demise. With him a very short, but intensively experienced period of our mutual past was borne to his grave.

I am mourning for a very good friend. Indeed, true friendship it was, although we found ourselves in a war against each other—he, the American destroyer commander, and I, the German submarine commander. But this war was only the dreadfully loathsome setup which compelled us to fight against each other, but in our hearts we naval men never felt hatred against each other….

When after two or three hours George’s destroyer “Corry” came up, an American sailor climbed down into the water up to his chest, in order to bundle me up within the liferaft, so I could be pulled up aboard for owing to the loss of blood I had been to weak to climb aboard by myself.

Although it was midday-time on a Sunday, and in the officers’ mess the table had been set for lunch, George ordered all dishes to be removed, and though I was smeared with diesel oil from top to toe I was put on the table in order to be operated. I was cleaned off oil, and before the young doctor Anderson of Swedish descent started surgery, George welcomed me as his guest aboard his ship, addressing me as “captain”, and offered me for the duration of my stay his bunk in the captain’s room. When the doctor was about to take off my right leg just above the knee, warning of the danger of gangrene, I protested, and the admirable physician willingly took great pains to save my leg, by re-moving dozens of fragments, by taking care of severed tendons, muscles and nerves and by heaping lots of penicillin onto the wound, before he devoted himself to the other injuries. When George was informed that I had to come round, he came to “my” bunk and advised me to pray that there would be no gangrene.

I have the most pleasant memories of my stay aboard the destroyer “Corry”, because it was marked by the chivalrous way of thinking by George, the American commander, who looked after me day by day, sitting at my bedside and devoting many hours to tell me about America, his family and his service in the navy. He never made me conscious of the fact, that meanwhile I had the status of a prisoner of war. I was, as he time and again emphasized, his guest. (Secretely I was not at all sad about my fate, since I was fed up to the brim with this kind of war, when German submarines were hunted like hares on account of the American superiority in radar and sonar, and I would have been even happy about the change in my fortune, if not so many of my crew had died.)

With his great tactfulness George never asked me a military or political question. When after a few days I was able to hobble about with my leg in thick plaster (and with a turban-like head bandage), George dragged me to sunny places on the upper deck and he insisted that I put my arm round his shoulder, not allowing anybody else to heave me about. Twice I was invited to have the evening meal in the officers’ mess, where I was assigned the seat of honour next to him. When subsequently a motion picture was shown, George bent underneath the table to push a cushion under my foot and kept inquiring about how I feel.

In my lifetime I have respected and admired George in view of his personality and his humanity. During manoeuvres I also got to know him as an extremely proficient mariner and as a man of cour-age to stand up for his humanitarian beliefs. When the admiral aboard the aircraft carrier “Block Island” ordered my transfer to his ship, George declined to execute this order with reference to my “critical condition”. When the “Corry” entered the harbour of Boston in the afternoon of March 29th, 1944, I, the German prisoner of war, stood next to the captain on the bridge and was even allowed for a short while to act as his helmsman. Saying goodbye to George I was on the verge of tears since we had become pretty close.

I had forebodings that in the forthcoming custody of the army I would in all probability have to go without this unique quality of George’s warmheartedness. (My premonitions proved true: at the Fort Devens army hospital I was referred to as the “Nazi subcommander”, ended up in a padded cell of “Section eight” for loonies and had to eat chops with a spoon, until I was “rescued” by naval intelligence officers.) On parting George gave me one of his khaki-uniforms, in which I looked very much American. When, lying on a stretcher, I left the “Corry” and his captain, the sailors showered masses of chocolate, cigarettes, chewing gum and other goodies upon me. While being carried over the gangway, all men on deck saluted to me, the German PoW. This generosity symbolizing a spirit of decency of mind was doubtlessly the result of George’s splendid example as a commander. To the best of my recollection I have told the story of George Hoffman a thousand times as that of a knight in shining armour in a heroic epic.

Dear Lois, at our age we are especially affected by the death of someone whom we love, becoming conscious of how quickly human life may come to an end. From my own sorrowful experience I know that the confrontation with the finality of death produces deep emotions which tend to brighten up the memories of the deceased in our heart. In my view the image of George cannot grow brighter than it has been up to now. He will always rank foremost among those few whom I consider an exceptionally good friend.

Very affectionately yours

Gunter

Less than three months after the Corry picked up Gunter Leopold, it struck a mine off the Normandy coast during the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings. More than two dozen of George Hoffman’s men were killed, and he himself barely survived: Hoffman was the last to leave the ship, which sank in only eight minutes, and he was pulled out of the water unconscious. Hoffman returned to the United States in July 1944. Leopold, who was being treated in a U.S. military hospital, found Hoffman’s address and the two began a regular lifelong exchange of letters, though they never met again.