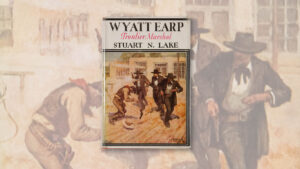

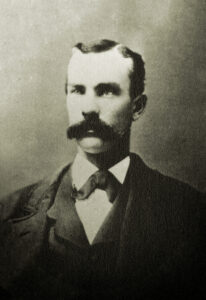

Virgil Earp, in ‘TOO TOUGH TO DIE’ tombstone, and John Kigran, in ‘Brutal Bodie,’ were both admired and shunned.

No towns or settlements in the Old West rivaled mining communities for action and drama. And among such communities, Tombstone, Arizona Territory, and Bodie, California, have received due attention and notoriety for their goings-on. Both towns were roaring in 1880–81, the population in Bodie reaching 6,000, in Tombstone upward of 5,000 and climbing. Young single men armed with guns and knives were ubiquitous, and for many of them saloons, gambling halls and bordellos were the institutions of choice. It was a dangerous mix.

In that era Tombstone hosted the infamous shootout near the O.K. Corral and other encounters involving the Earp brothers, Doc Holliday, Luke Short, Milt Joyce, Buckskin Frank Leslie and others. Bodie was even more on the wild side, witnessing 70 shooting incidents and nearly 30 murders between 1878 and 1882, which translates to a homicide rate 10 times that of present-day Chicago.

Two tested lawmen ran the shows, and their backgrounds show parallels. Bodie’s badge-wearer was John Franklin Kirgan, who was born in Kentucky in 1828 and served with an Illinois regiment in the 1846–48 Mexican War before news of gold lured him to California. Watching over Tombstone was Virgil Earp, born in Kentucky in 1843, who also served in an Illinois Regiment, during the Civil War, before joining his family in California. Later, Wyatt’s older brother would venture to Arizona Territory.

Kirgan engaged in mining and ranching in central and northern California, then drifted to Nevada, where he worked a couple of stints as a guard at the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. By mid-1877 he was back west in Bodie, then entering its gold bonanza period. By year’s end he had convinced townspeople of his knowledge of prisons, and they hired him to build a jail with two cells and a small office. In early January 1878 Kirgan opened a saloon, but he reportedly sold it just a week later for a nice profit. That March the jack-of-all-trades was appointed constable of Bodie, working with Justice of the Peace D. Virgil Goodson.

Earp bounced between California, Missouri and Wyoming as a farmer and railway worker before moving to Prescott, Arizona Territory, in 1877. There he did turns as a stage driver and sawmill operator while working a mining claim. During a wild street shootout that October he came to the aid of U.S. Marshal Wiley Standifer and Sheriff Ed Bowers, gunning down one of the troublemakers. Having made an impression, Earp served as a night watchman and then constable in Prescott, the territorial capital, making the acquaintance of Secretary/Acting Governor John Gosper and U.S. Marshal Crawley Dake. In November 1879, on learning Earp was bound for Tombstone, Dake appointed him deputy U.S. marshal for Pima County, to serve in the Tombstone mining district.

The lawmen naturally shared duties in common, such as patrolling, collecting taxes, verifying licenses (for saloons, bordellos, etc.), responding to gunplay or other violent acts and, in the case of major fires, keeping a lid on crowd control and looting. Their roles also differed in aspects. Kirgan doubled as the jail cook (a fairly decent one, by all accounts) and was known from time to time to provide “medicinal” booze or opium to those in his charge. Bodie had a far larger Chinatown than Tombstone, and it was the scene of rampant crime and violence. Earp’s duties, by contrast, often took him out of town, such as posse work and the transport of prisoners.

Their authority also had different origins. As a deputy U.S. marshal, Earp could act in a wide arc in and around town, and for much of his time there he also served as marshal of Tombstone, the county seat. While Cochise County Sheriff John Behan ostensibly had a measure of influence, he was no match for Earp’s authority or force of personality.

Kirgan’s authority in Bodie was blurred, in part because Bridgeport, not Bodie, was the seat of Mono County. He was initially appointed a constable serving alongside a justice of the peace, not to mention his duties as bailiff and jailer. As Sheriff Pete Taylor was a buddy, Kirgan was soon appointed a Mono County deputy sheriff as well. However, the office of sheriff was contested in the courts, so Kirgan’s Bridgeport connections were weak.

The typical historical appraisal contends that both Earp and Kirgan were largely effective lawmen in their respective towns. There is no question the vigorous times put both through extreme trials.

Tombstone city officials were generally pleased with Earp’s performance as a deputy U.S. marshal and several times appointed him town marshal. Still, his hold on authority was shaky. When Town Marshal Fred White was killed in a controversial October 1880 accidental shooting, Earp was appointed to replace him. Yet in a special election that November he lost to Ben Sippy, and Sippy also won the regular election in January 1881. Only when Sippy skipped town that summer over bad debts was Earp again appointed town marshal. In the wake of the Oct. 26, 1881, shootout of O.K. Corral fame, when Ike Clanton pressed murder charges against Virgil, his brothers Wyatt and Morgan and Doc Holliday, the town council suspended Virgil from his post.

Kirgan’s Bodie was far more dangerous ground, between the many shootings, duels, gambling quarrels, Chinatown vice and so forth. On one occasion a prisoner “left jail” and was later lynched, prompting Kirgan’s dismissal as jailer, though he remained a deputy sheriff. Like Earp, he lost an election for constable, was later reappointed to the position and in general faced a rocky road. Even so, during Bodie’s boom years, when some half-dozen constables and deputies roamed the streets, Kirgan was the one in charge.

After being crippled in the left arm during a Dec. 28, 1881, assassination attempt on the streets of Tombstone, Earp pursued mining, business and, yes, law enforcement positions in California, Arizona Territory and Nevada, where he died at age 62 on Oct. 19, 1905. Kirgan never left Bodie. On March 6, 1881, as he drove through town in a sulky, his horse bolted, pitching Kirgan onto the frozen muddy street. The 53-year-old died of his injuries on March 16 and was buried in Bodie.

Thus went the lively careers of two lawmen who were respected and knew what they were doing, yet were not always able to please their bosses, let alone voters. If John Kirgan and Virgil Earp had difficulty asserting their authority or reassuring fellow citizens, one can imagine the hardships of being a policeman, deputy sheriff, constable or any other kind of lawman on the American frontier.