Once the Rebels took aim at Fort Sumter, there was no turning back—for anyone.

Secession was a bone of contention charged with enough lightning to kill half a generation if it hadn’t been run to ground sooner. The fact that the flashpoint burst in Charleston is no surprise; they’d been gnawing around that issue for 20 years, but if it hadn’t happened there, it would have happened someplace else— that’s how volatile the thing was. Or was it? Here is the set up: On November 6, 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president on a Republican Party platform that would have made slavery illegal in any new territory or state of the Union, but did not call for the outright abolition of slavery in the South, where it already existed. A number of Southerners still saw this as a threat to their political power, because it would eventually install a permanent majority of the U.S. Senate hailing from free states, who would be in opposition to Southern interests, and in due course would probably lead to the abolition of slavery by federal law.

Other Southerners saw the Republican victory more perniciously—as an immediate and direct threat to the South’s “peculiar institution.” This was the result of 30 years of haranguing by Northern abolitionist groups who had now associated themselves with the Republicans, and the distinctions between what the Republicans were actually saying, and what the abolitionists were advocating, were fatally blurred because the abolitionists continued to shout so loudly.

That, in turn, worked up the Southern Fire Eaters, who preached that as soon as Lincoln took office, he would abolish slavery. And no matter what Lincoln or the Republican platform said to the contrary, nobody in the South would believe it because the abolitionists had been calling Southerners ugly names for so long and threatening John Brown–style abolition. For their part, the Fire Eaters responded by painting abolitionists and Republicans as worse than the devil himself, and certainly no better than common thieves and economy wreckers. What was a Southerner to do?

On December 20, before Lincoln could even be inaugurated, the South Carolina legislature—in plain sight of the Yankee soldiers occupying the forts of Charleston Harbor, including Fort Sumter—met and drew up an ordinance seceding from the Union.

This prompted similar rumblings in other states, including Louisiana, where William Tecumseh Sherman had just been named superintendent of the Louisiana State Military Academy (now Louisiana State University). On Christmas Eve, Sherman was having dinner with the ancient languages teacher, a Mr. Boyd, when word of South Carolina’s secession reached him. Sherman rose from the table and spake thusly:

“You people of the South don’t know what you are doing! This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don’t know what you’re talking about. You mistake the people of the North. They are a peaceable people, but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it!”

The fiery Sherman then climbed even higher on his soapbox before the startled professor Boyd.

“Besides,” he demanded,“where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or a rail-way car, hardly a yard of cloth or a pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on earth—right at your doors!”

Then he revealed a prophecy:

“You are bound to fail! Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, and with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see that in the end you must surely fail.”

Professor Boyd’s reaction to this extraordinary tirade went unrecorded, but the outburst summed up the situation about as well as ever has been done off-the-cuff. Within a short time Sherman had resigned his position and made his way north, as more states cast their lot with the Southern Confederacy.

The ominous undertaking by the South Carolina Legislature caused Major Robert Anderson, commanding the 85-man Federal garrison of Charleston, to secretly collect his men a few days afterward and move them into the unfinished Fort Sumter, named after a Revolutionary War hero. Anderson concluded that the pentagonal fort, with walls 12 feet thick, and located on a man-made island of rocks and spoil guarding the outer entrance to the harbor, was the safest place for his bluecoats in the midst of this hornets’ nest of sedition.

By February 1, 1861, seven states of the Deep South—the cotton South—had seceded one after the other—all prior to Lincoln’s inauguration—and as they did, their local militias—peaceably, but forcefully—took over Union arsenals and installations and hauled up the Confederate flag. Soon there remained only four Federal fortresses in the whole seceded South that continued to fly Old Glory, and Sumter was among them. For the good citizens of Charleston, however, this was like having an open sore stinking up the beauty of their fashionable waterfront Battery promenade. It simply would not do.

In January, a relief steamer, Star of the West (destined for an interesting future in Civil War lore), had been dispatched by outgoing President James Buchanan to bring provisions to Fort Sumter, but was summarily fired upon and repulsed by artillerists from the Citadel, South Carolina’s military college, who were the most experienced cannoneers in the state.

However, the man ultimately selected to remove the canker in Charleston Harbor was a newly commissioned Confederate brigadier general with the remarkable name of Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. A veteran of the Mexican War, Beauregard was the Creole scion of a wealthy family of Louisiana planters, whose first language was French, and with all the temperament that went with it. He had graduated second in his West Point class of ’38, where his artillery instructor had been the very man who was presently peering at him through a spyglass from the ramparts of Fort Sumter, a couple of miles away—Major Robert Anderson. Thus a challenging confrontation was now afoot, but it did not have to be.

First, as the Deep South states began seceding, a group of respected but alarmed politicians in the North and in border slave states cobbled together a “Peace Conference,” which met in Washington in February 1861, in hopes of defusing the crisis. Led by former President John Tyler, of Virginia, its members consisted mostly of former senators, congressmen and governors who believed the weight of their influence and seniority would allow them to introduce compromise legislation to Congress that would permanently resolve the issue of secession and slavery.

The conference met at Washington’s famed Willard Hotel and was even accorded a courtesy visit with a yet-to-be-inaugurated Abraham Lincoln, but to no avail. Congress also had been working on similar legislation, led by the hard-striving, long-suffering Senator John Crittenden of Kentucky, a fossil of the War of 1812 and veritable compromiser in chief of long standing. Crittenden’s solution was to enact amendments to the U.S. Constitution which, to appease the South, would have protected slavery in perpetuity in the states where it existed, which was about the same notion that the peace conference ultimately arrived at.

In fact, Crittenden actually succeeded in getting passed what would have been the 13th Amendment, guaranteeing slavery forever in the South, but the events at Fort Sumter trumped this Faustian bargain and the matter died moot, with the warring states deciding to fight it out instead. (Crittenden was perhaps the supreme poster figure of a man caught in the middle in the War Between the States. His Kentucky was a contentious battleground between North and South and both his sons became major generals in opposing armies. Crittenden himself died at age 75 in July 1863, right in the middle of the thing, but with the satisfaction a few days earlier of knowing that after the Confederate losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, his beloved Union likely would be saved).

While all that was going on, Fort Sumter languished in the harbor as a bilious insult to the palates of proper Charlestonians and not-so-proper Charlestonians alike (slaves excluded), while General Beauregard stuck to his original plan to starve the intruders out.

Meantime, despite Sherman’s dire prophecy, the South was busy calculating its odds. It was a given that one Southerner could whip a minimum of 10 Yankees, which canceled out the population differential. And so far as materiel and supplies went, they could easily be purchased from England and France, whose busy looms fairly cried for Southern cotton. And never mind that up in his Washington headquarters corpulent old Winfield Scott, head of the U.S. Army, was dreaming up his “Anaconda Plan” to blockade the Southern ports—England and France would never stand for that, and would bring their great navies to break any Union blockade.

Many Southerners did not think it would come to war. After all, Jefferson Davis had said it for all of them when he declared, “We only want to be let alone.” Not only that, Davis backed it up by sending a three-man peace commission to Washington to work out details of a peaceful separation with the Lincoln administration. The commissioners, all well-known and highly respected citizens, were sanctioned to “speedily adjust” (i.e., pay for) all seized federal property on Southern soil, as well as for the South’s share of the national debt. They also had approval to offer the U.S. government free access to the mouth of the Mississippi River, in exchange for giving up the remaining forts, including Fort Sumter.

Lincoln refused to see them, on grounds that it would appear to give legitimacy to the seceded states, but through their own political contacts they were able to intercede with some Cabinet members through third parties.

On March 4, 1861, three days after Beauregard was appointed to lead the Confederate Army, Lincoln was finally inaugurated in Washington. On the East Portico of the Capitol, whose huge dome had yet to be finished, he was sworn in, and delivered these conciliatory words in his inaugural address:

“I have no purpose, directly, or indirectly, to interfere with slavery in the states where it now exists,” he said.“I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

He then went on to declare that secession was unlawful under the Constitution, and that the laws—including the occupation of government property and the payment of duties and taxes— would be enforced, then concluded with a message and a warning to the South:

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government, while I have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect, and defend’ it.”

When the telegraph brought them this news, the people of the Deep South scoffed. They didn’t believe him, and even if they had, it didn’t matter anyway because he wasn’t their president. Jefferson Davis was their president.

There was a misunderstanding that might have prompted the firing on Fort Sumter. On March 15, Lincoln had polled his Cabinet on the issue and the consensus was that Sumter should be abandoned. That same day, Secretary of State William Seward let it be known to the Confederate peace commission that Lincoln planned to evacuate the fort, and this was passed along to the Rebel capitol in Montgomery, which rejoiced at the news.

But two weeks later the Federal soldiers were still in the fort, and when inquiries were made, Seward claimed the president had changed his mind; that while there would be no attempt to reinforce Fort Sumter, a naval expedition was on the way to resupply it. The reaction in the Rebel capitol was furious, and the immediate assumption was that Lincoln had lied, or at least was trying to deceive them. On April 6, Lincoln signed the order releasing the Union flotilla to provision Sumter, and two days later a Federal messenger arrived at the South Carolina governor’s office with word straight from Lincoln that an attempt would be made to bring provisions to the men in the fort, and that if this was permitted, there would be no further attempt to strengthen the garrison.

Davis and his administration saw this for what it was: Lincoln had contrived to make them fire the first shot—and to prevent food from reaching hungry men, at that. The crisis had now reached its zenith. Allowing the North to resupply Sumter indefinitely would make the Confederacy look ridiculous in the eyes of the world (let alone the Charlestonians) but to fire on the resupply ships, or the fort, would not only make them look at fault, but bring on the dreaded civil war.

For a man like Jefferson Davis it was a painful but obvious decision. He told his secretary of war to authorize Beauregard to blow Fort Sumter into brickbats.

Instead, Beauregard sent out two men in a rowboat with an offer to remove his old artillery instructor and his command from the premises, with all their arms and property, and even to permit them a formal salute when they lowered the U.S. flag. Anderson naturally refused, but confided to the two Confederate emissaries, “Gentlemen, if you do not batter us to pieces, we shall be starved out in a few days.”

This last remark prompted more parley, but in the end an order was given to “reduce the fort.”

At that point a great convulsion of reality seemed to seize the Rebel high command. The gravity of the situation apparently sank in when they realized that whoever fired the first shot would, in effect, be responsible for starting a civil war that now held every promise, as Sherman had predicted, to “drench the country in blood.”

First choice was given to a Virginian, Roger Pryor, who had recently resigned his seat in Congress and traveled to Charleston to stir up trouble. A shiver of fear must have run through him, though, because after all his bombast, he declined the honor.

Finally someone produced old Edmund Ruffin, a septuagenarian farmer and ardent secessionist who loathed Yankees with a hatred that was almost obscene. At 4:30 a.m., so the story goes, Ruffin was handed a lanyard to one of Beauregard’s 32-pounder howitzers, and in a thunderous flash against the April darkness the Civil War began.

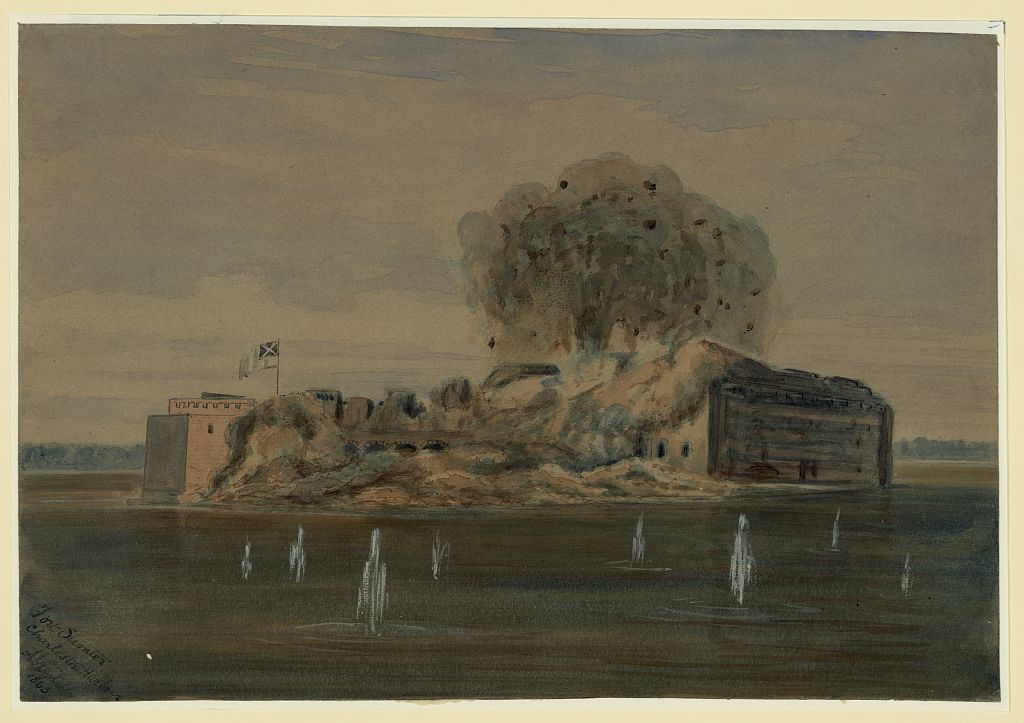

The shell arced across the harbor toward the pentagonal fort where Anderson’s men slept fitfully in the casemates beneath the ramparts. Other guns spoke, as well as huge 13-inch mortars—with shells “as big as a full-grown hog”—the first of some 4,000 artillery rounds expended in the siege. Heavy shot smashed bricks to dust and set the mighty fortress to trembling and quaking. Shells burst overhead and splattered Sumter’s open interior with shrapnel while hot shot tore through the dark sky like flaming red meteors and started fires that threatened the powder magazine.

Anderson and his men were relatively safe beneath the ramparts, but the fort’s guns had been designed to fire directly at enemy ships and could not be elevated enough to reach their tormentors ashore. They fired them anyway, just for the hell of it, and at one point the Rebel gunners gave them a cheer for their efforts. A Rebel shot dismasted the Union flag but a soldier put it back up. Lincoln’s relief flotilla had just arrived but did not enter the harbor to provision Anderson’s men, or to help in any other way.

The bombardment continued all through that day and night and into the next. Charlestonians, as well as others who had arrived from the countryside, promenaded up and down the Battery and through the streets, and from the rooftops they cheered and clapped each other on the back.

Next day, April 13, as the cannonade seemed to reach its most pitiless crescendo, Rebel artillery spotters heralded a white flag being run up inside the embattled fort. Anderson had had enough. His men were down to their last scrap of bacon, and before long somebody was likely to get hurt (so far there were no casualties on either side).

The Confederates allowed Anderson and his men to surrender on the same terms offered earlier, to salute their flag and march out of the fort on their own hook to a steamer from the relief flotilla that would take them north toward home.

It was, of course, the pretext for Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers from the remaining states to put the rebellion down. At this,Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas promptly seceded rather than make war on their fellow Southerners.

Would things have turned out differently in the end if Lincoln had not insisted on resupplying Anderson and his force at Fort Sumter, or if Jeff Davis had ordered Beauregard to hold his fire— or other unknowable “what ifs”? At the least it might have given the forces of peace and reason a second chance, and bought time for a sober appraisal on both sides of the terrible thing they were about to set into motion. On the other hand, there had already been a lot of second chances, and to the hotheads, North and South, Sumter seemed as good a place as any to start a fight.

And oh, that 13th Amendment that Senator Crittenden had pushed through that would have guaranteed slavery forever in the South—the one that died before it could be ratified by the states? It was revived by the Senate on April 8, 1864, almost three years to the day of the firing on Fort Sumter. Except this time it called for the abolition of slavery throughout the nation, forever. It was ratified and adopted into constitutional law on December 6, 1865.

Novelist and historian Winston Groom is the author of Forrest Gump and several Civil War histories. His next book, Kearny’s March: The Epic Creation of the American West, 1846-1847, is scheduled for release this fall from Alfred A. Knopf.

Originally published in the March 2011 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.