In 1913 the freed Apache prisoners of ‘Geronimo’s band’ had to choose whether to remain in Oklahoma or move to a reservation in New Mexico

A regal, silver-haired Mildred Cleghorn warmly greeted a newspaper reporter at her Apache, Oklahoma, home in September 1996 to discuss her storied life. Cleghorn, then 85, spoke with grace and candor as she reminisced about her 18-year reign as chairwoman of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, as well as her family’s unique history.

Cleghorn specifically recalled one of her earliest memories, at age 3 in 1914, riding in the family’s horse-drawn wagon from the Fort Sill Military Reservation to their 40-acre government allotment near Apache. Only later would she learn those were among her first moments of freedom. She’d been born a prisoner of war at Fort Sill on Dec. 11, 1910.

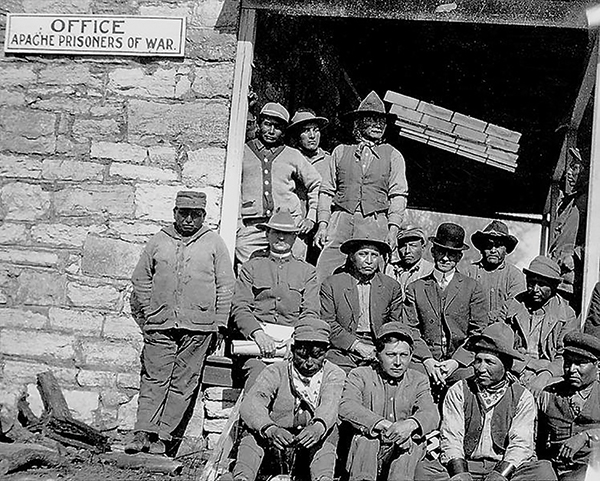

For the Chiricahua Apaches of Cleghorn’s generation—a people branded “Geronimo’s band,” for better or worse—her story was hardly uncommon. Their collective journey through captivity began in September 1886 with Geronimo’s surrender to U.S. troops and ended in 1913 after an Act of Congress. By then the absurdity of their continued imprisonment had already been revealed in Washington, D.C., and beyond.

“Their few survivors and their much more numerous descendants—their children and their children’s children—are still ‘prisoners of war,’” argued one humanitarian activist in a 1912 article for The North American Review literary magazine. “There are among the band men and women of full age who were born into that condition and have grown to maturity without knowing any other lot.”

The full gravity of those 27 years of captivity hit home for the Chiricahuas on April 2, 1913, a bittersweet day in their history known as “the Parting.”

Tears of joy and pain flowed simultaneously that spring afternoon with the numbing realization that while the Apaches were no longer prisoners of war, their freedom had arrived at a tragic price. Over nearly three decades of imprisonment their population had dwindled from 506 souls to the final tally of 257 (138 males and 119 females) enumerated by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The steep decline reflected the disease and hardship that had shadowed them from mosquito-infested prison camps in Florida and Alabama before their October 1894 arrival at Fort Sill on the southwest Oklahoma prairie.

Yet one last heart-wrenching act stood between the Chiricahuas and freedom as they gathered that day in early April 1913 at the Rock Island Railroad yard. Of the remaining 257 prisoners, 190 had chosen to return to a portion of their ancestral homeland in New Mexico, where they aspired to begin new lives among “cousins” on the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. That fateful decision also meant they would have to bid farewell to the 67 other Chiricahuas who chose to remain at Fort Sill and await promised allotments.

For a people accustomed to harsh existence and anguish, the Parting still hit like an anvil. “The day of separation was a great day of sorrow,” said Raymond Loco, grandson of Chief Loco and another designated a POW at birth. “There was weeping and wailing.…When they were on the train [to New Mexico], they were in a sense of puzzlement. What’s going to happen to us?” Loco noted his fellow Apaches “were not happy—they were disturbed.” Blossom Haozous, the half-blood daughter of Chiricahua interpreter and loyalist George Wratten, defined the moment as “one of extreme emotion.” She added, “The Mescalero-bound Apaches were leaving behind relatives and friends and once again faced an uncertain future.”

They also left behind their dead, perhaps the most painful parting of all. Naiche, the Chiricahuas’ last hereditary chief, buried two wives and eight children at Fort Sill’s Apache prisoner of war cemetery on Beef Creek. The chief himself died of influenza on March 16, 1919, six years after his arrival in Mescalero, and was buried there more than 400 miles from his loved ones. Eugene Chihuahua—son of Chief Chihuahua, who died in captivity in 1901—and his wife were also in the party bound for New Mexico. They left the graves of six children at Fort Sill.

The cemetery haunted every Apache family in those final hours. “Hardest of all was forsaking our beloved dead,” recalled Asa Daklugie, then about 40 years old and among those who had championed the move to New Mexico. “Quietly we visited the resting places of our people for a last farewell. We knew that they were in the Happy Place, awaiting our coming. We knew that they understood and that they approved our leaving.”

Five passenger cars, eight stock cars and two baggage cars awaited the 190 departing Apaches, along with many of their beloved dogs. Authorities told the freed prisoners pets would be strictly forbidden on the 36-hour trip to the Mescalero reservation, but the Rock Island crew showed mercy and looked the other way. On the train’s arrival in New Mexico one bystander watched with amusement as dogs “simply ‘boiled out’ of the cars.”

Intrigue trailed the Chiricahuas on their journey west, especially among New Mexicans braced for an uprising by Geronimo’s band. In Tucumcari the local newspaper reported how a group of schoolteachers appeared at the railroad station with their students to gawk at the “wild Injuns.” They were disappointed to find a quiet and somewhat weary band of travelers, including a few elderly women “munching away on big quids of Star Plug.” The reporter summed up the visit tongue in cheek: “The Apaches did not appear half so fierce as they are depicted in the dime novel. In fact, some of them looked to be quite respectable citizens.”

Inflamed rhetoric by New Mexican politicians and prominent cattlemen over the preceding months had heightened fears over the removal of the Chiricahuas to their state. Though Geronimo himself had died in 1909, his notoriety as a savage warrior still evoked fear in the region, and detractors relentlessly played to those fears. On Aug. 19, 1912, U.S. Senator Thomas B. Catron of New Mexico declared to colleagues his vehement opposition to the Apache resettlement. “Those Indians have been the worst band of Indians that have ever existed upon the American continent,” he said. “They have been the most warlike; they have been the most desperate, the most bloodthirsty and murdering that has ever existed.” Five days later, over such objections, Congress approved the Indian Appropriation Act, sanctioning the release and relocation of the Chiricahua prisoners.

Albert B. Fall, Catron’s fellow senator from New Mexico, was even more outspoken about the Apache relocation. Five days before their formal release he rose in the Senate chamber to deliver one last fiery speech on the issue. In it he shamelessly revived old fears, relating his initial arrival to New Mexico Territory decades earlier at Silver City, where he stepped from a train to see “an American holding in his hand the bleeding scalp of a woman who had been killed by one of these Fort Sill Apaches.” Fall then theatrically asked, “Is it possible there is not sufficient land in all these great United States to which these Indians can be taken and where they can be kept without forcing them back to live among the people whose relatives they murdered?”

Fall failed to reveal an ulterior motive for not wanting the Chiricahua Apaches to settle on the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. Months earlier J.W. Prude, a Tularosa, N.M., merchant who ran a trading business at Mescalero, publicly called out Fall on the issue. Prude said he was unaware of any such white descendants of Apache victims living in the area, as so “graphically” described by the senator. He further stated that anyone who uttered “such rot” did so “for a cold-blooded selfish motive,” and he insinuated Fall had one. The merchant claimed Fall leased large swaths of grazing land on the reservation for his sheep herds and didn’t want anyone infringing on his lucrative business. For his part, Prude admitted his trading business at Mescalero would benefit from the Apache relocation.

Guilty or not, the Chiricahuas of Fall’s rhetoric were largely a memory by 1913. For starters, the fearsome Geronimo was no more. On Feb. 17, 1909, after having fallen drunk from his horse and lain in a puddle overnight, he died at age 79 of pneumonia. Prior to the release of the surviving prisoners Secretary of War Stimson had compiled a list for the Senate that revealed another reality. Only 30 men on the list had been involved in hostilities decades earlier, and all but one of them were in their mid-40s or older. Only six of the warriors who had surrendered with Geronimo in 1886 remained alive.

Incarceration had ushered in a starkly different kind of life for the Apaches from the nomadic existence of their forefathers. Foremost among the changes was their transition to a cash economy through the sale of cattle, surplus crops, hay and contracts for drilling wells—the proceeds of which were deposited into a trust for the benefit of all. By 1913 they had become successful cattlemen, amassing nearly 6,000 high-grade Herefords, which they sold to a Texas buyer for $228,800 and divvied the profits. The Chiricahuas excelled in numerous aspects of modern life and even fielded a standout baseball team. Geronimo capitalized on his notoriety, accepting invitations to attend the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and ride horseback in President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1905 inaugural parade in Washington, D.C. In St. Louis Geronimo charged 10 cents for his autograph and as much as $2 for a photo, prompting one customer to famously exclaim, “The old gentleman is pretty high priced, but then he is the only Geronimo.”

But Geronimo’s reputation as a merciless warrior continued to shadow his people like an eclipse—even in death. Stories of the Chiricahuas’ fighting prowess also persisted over their nearly three decades of incarceration. Dime novels and yellow journalism helped breathe life into the old reputation for a new generation of Americans, though the Apaches themselves had to admit aspects of the fantastical stories were rooted in truth.

Warm Springs Apache elder Sam Haozous shed light on that violent past weeks before his death in 1957 when he sat down before a tape recorder to preserve his remembrances for his family. Haozous, 88, recalled his band’s forced removal from their New Mexico home of Ojo Caliente—their sacred Warm Springs—to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona Territory when he was 8. Haozous and the others arrived at San Carlos on May 20, 1877, with a shackled Geronimo and other imprisoned leaders in tow.

By the next spring Geronimo had bolted the reservation for Mexico, triggering nine years of broken promises, breakouts and deadly resistance. Young Haozous experienced those harrowing times firsthand when his family also fled San Carlos. They left due to harsh conditions and the conviction they’d been unjustly ripped from their beloved Ojo Caliente. Housed in the University of Oklahoma’s Western History Collection, Haozous’ 1957 recording offers a graphic account of the hardships and bloodshed his family experienced as fugitives alongside Geronimo.

The elderly Haozous described an apocalyptic world in which death was always a heartbeat away. He recounted one startling incident in 1882 when Mexican soldiers attacked their party near a dry creek bed on the Janos Plains. During the fight he watched a mother strangle her baby to death, defiantly proclaiming, “I don’t want my baby to be a slave to these Mexicans.”

Haozous and other young Apaches contributed to their survival by running ammunition to the warriors during battles. He marveled at how a lone Apache warrior could fend off as many as 150 of the enemy by dodging among various mountain fastnesses. He also recalled how the band staved off starvation by eating rats or boiling animal bones for the marrow to make broth.

Geronimo fostered a merciless mindset. “No wonder they call him a famous warrior,” Haozous said of the ruthless leader. “I seen what he do. He kill the people…but he don’t care—woman, or white woman, or Mexican woman—he killed everybody. It don’t make no difference. Even baby. When the war started, he given his men order, he said, ‘Don’t save any of them. Don’t save even a baby. Just kill them all.’” Modern-era historians refer to such no-holds-barred combat as total war.

In the end Geronimo’s greatest fight became the one for his freedom. For decades after his surrender he lobbied authorities to be freed and returned to the home of his birth on the upper Gila River in Arizona Territory. He finally secured a council with President Roosevelt on March 9, 1905, four days after having ridden in his inaugural parade. Overwhelmed by the emotions of the moment, Geronimo spoke with a rare eloquence: “Great Father, my hands are tied as with rope. My heart is no longer bad. I will tell my people to obey no chief but the Great White Chief. I pray you to cut the ropes and make me free. Let me die in my own country, an old man who has been punished enough and is free.”

Roosevelt sympathetically told Geronimo that Arizona’s white settlers still harbored great anger toward the Chiricahuas, and he feared their return to that territory would only result in “more war and more bloodshed.” New Mexican leaders would use the same reasoning in their subsequent attempt to block the relocation of the former prisoners to their state. By then Geronimo had died in captivity at Fort Sill.

One bitter chapter after another marked the Apaches’ time in captivity, but the push for freedom only gathered steam. In 1913 the Rev. Walter C. Roe, who helped establish a mission for the prisoners, wrote an impassioned appeal on their behalf. “It will be literally true that the iniquity of the fathers is visited upon the children unto the third and fourth generation if this thing goes on much longer,” he wrote. “Shall innocent babies be born prisoners and harmless, laughing children grow up in captivity because their grandfathers fought against or possibly for—think of it, possibly for—the United States government?”

Roe’s words could have been aimed at the woeful tale of Chatto, who once fought alongside Geronimo only to become an Apache scout for the Army. In March 1886 Chatto assisted Brig. Gen. George Crook with his pursuit of Geronimo in Mexico’s Sierra Madre—a deed that forever branded the scout a traitor among the Geronimo loyalists of his tribe. Four months later Chatto joined an Apache delegation to Washington, D.C., beseeching authorities to allow them to remain on the reservation at Fort Apache, Arizona Territory. Secretary of the Interior L.Q.C. Lamar presented Chatto with a silver medal, while Secretary of War William Endicott gave him an elaborate certificate and led the delegates to believe their request had been granted. It hadn’t.

On the return journey soldiers at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., detained Chatto and party. Abruptly placed under arrest, the hapless delegates were shipped to Florida to join their Apache brethren as prisoners of war. Four years later Crook visited the prisoners at Alabama’s Mount Vernon Barracks. During the general’s visit Chatto removed the silver medal from his breast and proffered it to Crook. “Why did they give me that, to wear in the guardhouse?” he asked. “I thought something good would come to me when they gave me that, but I have been in confinement ever since I have had it.”

Chatto, unlike Geronimo, lived to see his freedom. On the day of the Parting, he chose to join those traveling to New Mexico, although he remained an outcast in many circles. Daklugie, who held Geronimo’s hand at his deathbed, was relieved when Chatto opted to settle at Apache Summit, some 10 miles east of the main encampment. “He knew he was unwelcome with us,” Daklugie coolly stated.

Chatto lived with the bitterness of his turncoat label until his death in 1934. The end arrived when his Ford Model T veered off a reservation road and flipped near Whitetail, N.M. He died at the scene—perhaps truly free at last.

Fifty-two years later, on the September 1986 centennial of Geronimo’s surrender, Cleghorn and other tribal members made a pilgrimage to their ancestral home in Arizona. Haozous, Cleghorn’s uncle, once told her of cave paintings he’d seen there as a child. The group found the paintings just as Haozous had described.

Each of them stared in awe. Then they wept.

Ron J. Jackson Jr. is an award-winning author from Rocky, Okla., and a regular contributor to Wild West. For further reading he recommends Indeh, an Apache Odyssey, by Eve Ball; The Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War, by John Anthony Turcheneske Jr.; Survival of the Spirit, by H. Henrietta Stockel; and Geronimo, by Angie Debo. This article was published in the August 2021 Wild West.