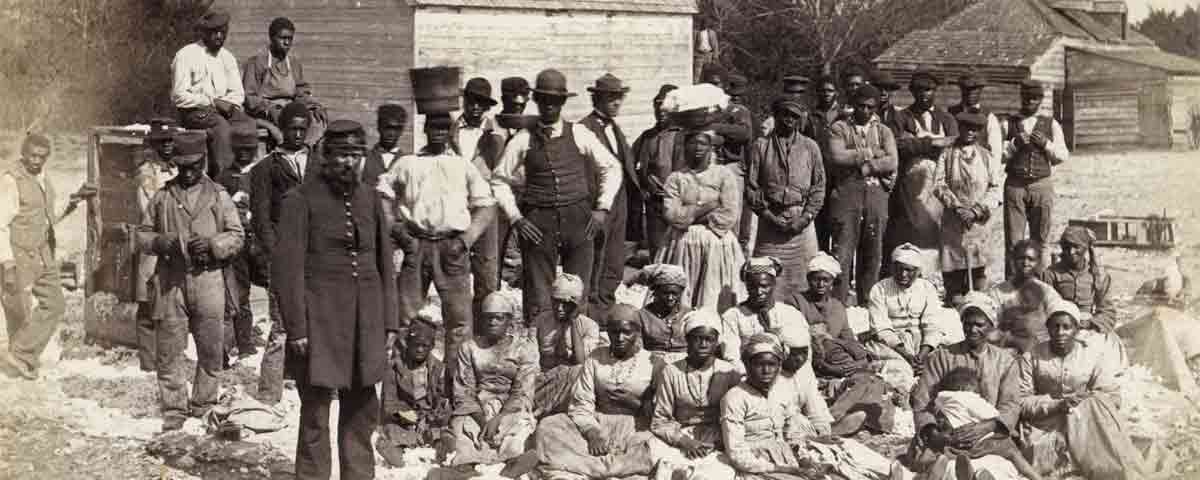

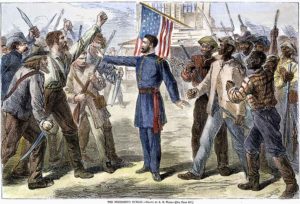

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n January 16, 1865, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15, which one admiring biographer lauded as “the single most revolutionary act in race relations in the Civil War.” The order promised thousands of freedmen 40-acre parcels of land located in a 30-mile wide swath from Charleston south along the Atlantic coast to the St. Johns River in Florida. But Southern-sympathetic Northern politicians and even Sherman himself would come to betray the famous order that gave freedmen “40 acres and a mule,” and former slaves would be forced off the land their families had worked for generations.

That Reconstruction betrayal drove many impoverished blacks from the South to Northern cities. The nation’s postwar leaders’ inability to possess the will, the wisdom, and the imagination to provide the black men and women, freed by the deaths of more than 750,000 Americans, with the means to rise economically affected American race relations for decades to come.

Sherman’s Special Field Orders No. 15 was an aggressive response to two issues that had bedeviled the Lincoln administration for nearly four years—the federal government’s confiscation of Rebel-owned property and the relocation of the thousands of contrabands who had found their way to Union Army camps. Repeated attempts to resolve these issues through legislation had collapsed in the face of the inflexible partisan positions staked out by Democrats and Republicans.

The first attempt to resolve the issue came in August 1861, with the First Confiscation Act declaring that all property used in aiding, abetting, or promoting the insurrection was “to be seized, confiscated, and condemned.” Fearful that the legislation might appear a desperate response to the Union defeat at First Bull Run, and might also be unconstitutional, Lincoln reluctantly signed the bill, and then immediately ordered Attorney General Edward Bates not to enforce its provisions. Lincoln’s timidity angered the more radical members of his party.

The following summer Lincoln again found himself at odds with several Republican members of congress. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull’s Second Confiscation Act authorized the government seizure of “all the estate and property, money, stocks, credits, and effects” of anyone in rebellion against the United States. Furthermore, “all slaves of persons…engaged in rebellion…that [come] under the control of the government of the United States…shall be forever free of their servitude.” The Second Confiscation Act lacked provisions for enforcement and proved no more effective than its predecessor.

Confiscation by the Union military, however, proved to be an altogether different matter. Commanders on the front lines seized abandoned Southern plantations and their slaves. But Congress and the Lincoln administration proved unable to dispel the uncertainty surrounding experiments in free labor by agreeing on policies for the seized lands.

Black leaders, wary of Congress and the administration, had put forth their own ideas regarding possible land redistribution. In November 1861, the Anglo-African newspaper published an editorial titled “What Shall Be Done with the Slaves?” that argued when the war ended “there will be four million free men and women and children, accustomed to toil” who should be awarded the confiscated land.

The growing likelihood that a Union victory would bring an end to chattel slavery led many black leaders to join the frequent calls for land redistribution. For tens of thousands of freedmen, ownership of the land they had labored on as slaves promised economic self-sufficiency and a path to citizenship. Nowhere was that promise more eagerly embraced than in Savannah in January 1865.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]Union Commanders on the Front lines seized abandoned Southern plantations and their slaves[/quote]

Sherman and his army had occupied that city following their seven- week march from Atlanta through northern Georgia. “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah,” he telegraphed the president on December 22. But controversy had tainted Sherman’s gift. On December 9, Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis had ordered a pontoon bridge over Ebenezeer Creek, near Savannah, disassembled before the freedmen traveling in the army’s wake could cross. The result, in the words of one Union cavalry officer, caused hundreds of blacks to rush “by the hundreds into the turbid stream,” where many drowned. Confederate forces captured those who remained on land. On January 9, 1865, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton arrived in Savannah to investigate the incident.

The secretary of war asked Sherman to arrange a meeting with leaders from Savannah’s black community. On Thursday evening, January 12, Stanton and Sherman got together with 20 ministers and lay leaders from the city’s black churches; at least 15 of the attendees had at one time been enslaved. In response to a question about how freedpeople could take care of themselves, 67-year-old Garrison Frazier, a former slave and the group’s spokesman, remarked that the best way was “to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor….” All but one of the group wanted to live separately from whites, “for there is a prejudice against us in the South that will take years to get over.”

Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15 four days after the meeting. It “reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States…the islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns River, Florida.” Subject to several bureaucratic strictures, “each family shall have a plot of not more than forty acres of tillable ground…in the possession of which land the military authorities will afford them protection, until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title.”

The order encouraged the enlistment of “young and able-bodied negroes” in the service of the United States, and guaranteed anyone enlisting the right to “locate his family in any one of the settlements at pleasure.” Finally, the order provided that “no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside; and the sole and exclusive management of affairs will be left to the freed people themselves, subject only to the United States military authority and the acts of Congress.”

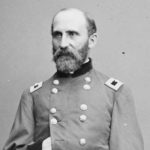

Michael Fellman argues in his book Citizen Sherman that Sherman solved a number of problems bothering him by issuing Special Field Orders No. 15, as the general had washed his hands of his “negro problem” by purging his columns of large numbers of black camp followers and passing them onto a man he despised, Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, the Union commander stationed at Port Royal, S.C.

Saxton, as inspector of settlements and plantations, was responsible for assigning each family 40 acres of land and furnishing a “possessory title” (which granted the right to use but not own the land, subject to the president’s approval). He sought and received assurances from Stanton that the federal government would not renege on its promise of land. Under Sherman’s orders, the Union Army also provided the freedmen with mules no longer fit for military use to work the land.

Saxton efficiently processed thousands of requests for land, and by June 1865, approximately 40,000 blacks had settled on 400,000 acres. Despite the enthusiastic response of the freedmen, the settlement of Sherman’s Reservation quickly encountered problems. One was largely practical. Many of the freedmen received their plots too late for spring planting. This created the need for temporary relief—the provision of food, clothing, and shelter—that the government was ill-prepared to meet. Of greater long-term significance was the change in political circumstances, as Sherman’s order was out of sync with the Lincoln administration’s evolving Reconstruction policy.

Freedman’s Friend

Rufus Saxton was an excellent choice to implement Sherman’s Field Orders No. 15. The Massachusetts native and West Pointer was an outspoken abolitionist and recipient of the Medal of Honor for his command of the Union defenses at Harpers Ferry in the spring of 1862. After his reassignment to South Carolina, Saxton was instrumental in the organization of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first official black regiment.

On March 3, 1865, less than two months after Sherman issued his order, the formation of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands added a new, often confusing layer of administrative oversight to the Sherman land grants. Although Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, commissioner of the Bureau, immediately ordered Saxton to continue his work, the heretofore autonomous venture in land redistribution was quickly caught up in larger political currents in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination.

Andrew Johnson’s ascendancy to the presidency in April 1865 marked the beginning of a bitter struggle over the seized lands, as he instituted a lenient policy of special pardons that restored most of the rights of former Confederates who swore an oath of allegiance to the United States. Simultaneously, Howard was putting the infant Freedmen’s Bureau on a collision course with the new president. His “Circular No. 13” issued on July 28, 1865, instructed bureau agents that land redistribution was the official policy, despite the president’s emerging amnesty program. Had Howard’s policy stood, as many as 900,000 acres of plantation lands previously belonging to slave owners might have been redistributed. But on August 16, the president countermanded Howard’s circular and said that if Southern whites obtained a pardon and paid their taxes, they could reclaim their land. In September, in response to a direct presidential order, Howard accepted strict new criteria for designating a property as “officially confiscated,” which in many places had the effect of ending land redistribution. By September 1865, many former owners of the land in the Sherman Reservation had begun demanding the return of their property based on the special presidential pardons. An order from President Johnson to Howard supported these claims.

Saxton’s sympathy for the freedmen virtually guaranteed that he would refuse to comply. “Thousands of them are already located on tracts of forty acres each,” he wrote Howard. “Their love of the soil and desire to own farms amounts to a passion—it appears to be the dearest hope of their lives.” Furthermore, Saxton argued in a second letter, “the faith of the Government is solemnly pledged to these people who have been faithful to it and we have no right now to dispossess them of their lands.”

Johnson’s second order to restore the lands also instructed Howard to negotiate a mutually satisfactory agreement between the freedmen and the former owners. The bureau commissioner’s first stop was Edisto Island, one of the Sea Islands off South Carolina. There he tried to get the freedmen to quit the land in return for guarantees that they would be hired by the land’s former owners. Edisto’s black residents refused and in response gave Howard a petition to deliver to Johnson. The freedmen argued they were not truly free without the land.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Saxton’s removal marked the death knell for land redistribution[/quote]

The petition remains a painful reminder of the sense of betrayal among the former slaves. “You ask us to forgive the landowners of our island,” wrote the petitioners. “You only lost your right arm [Howard had been wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks in 1862] in the war and might forgive them. The man who tied me to a tree and gave me 39 lashes; who stripped and flogged my mother & sister & …who combines with others to keep away land from me…that man, I cannot well forgive. Does it look as if he has forgiven me,” asked the petitioners, “since he tries to keep me in a condition of helplessness?”

Howard reported the refusal to Stanton. The secretary of war, whose animosity to the new president would eventually lead to his dismissal and Johnson’s subsequent impeachment, suggested that Howard’s only obligation was to try to get an agreement. If an understanding was not forthcoming, the blacks could stay. The Edisto petition, however, fell on deaf ears in Washington, and on January 15, 1866, Johnson ordered Saxton removed from his position.

Two weeks later, William Henry Trescot, who was in Washington to lobby on behalf of those South Carolinians whose lands had been confiscated, met with Sherman and other officers to discuss the genesis of Special Field Orders No. 15. Sherman told the group that his intention was to offer a temporary solution. In a follow-up letter to the president, he wrote, “I knew of course we could not convey title and merely provided ‘possessory’ titles, to be good as long as War and our Military Power lasted. I merely aimed to make provision for the Negroes who were absolutely dependent upon us, leaving the value of their possessions to be determined by after events or legislation.” As one historian has argued, “What the general had managed in No. 15 was a strategist’s version of bait and switch, at once a magnetic distraction for black people and sufficiently high-minded to leave the secretary [Stanton]…‘cured of that Negro nonsense.’”

Saxton’s removal in early 1866 sounded the death knell for land redistribution to the freedmen. Ordered by the president to return the confiscated land in a way that was mutually agreeable to the original owners and the freed people who had claimed it, Howard set out to do the impossible. White Southerners’ resistance to land ownership by blacks proved intense. The “feeling against any ownership of land by negroes is so strong,” wrote one Alabamian, “that the man who should sell small tracts to them would be in actual personal danger.”

The restoration of confiscated lands to their antebellum owners proceeded at a breakneck pace. On January 31, 1866, the Freedmen’s Bureau controlled 223,600 acres; within 18 months that total had shrunk to 75,329 acres. In July 1866, the congressional reauthorization of the Freedmen’s Bureau included a provision returning all the lands included in the Sherman Reservation to their original owners. Those freed people continuing to occupy confiscated land were generally given a choice: Sign work contracts, thereby accepting peonage, or leave. Most left.

The Johnson administration’s determination to restore the antebellum patterns of landownership alarmed many in Congress who continued to seek a means of offering freedmen their own land. Signed into law on June 21, 1866, the Southern Homestead Act opened 46 million acres of public lands in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi to settlement. Until June 1868, the land was divided into 80-acre parcels; thereafter the size of the parcels doubled to 160 acres. Homesteaders could not purchase the property. They had to occupy and improve the land for five years before acquiring full ownership.

Ex-Confederates were banned from obtaining land, but only until January 1, 1867. George Julian, an Indiana congressman and longtime opponent of slavery, had drafted the most important provision of the law. “No distinction or discrimination shall be made in the construction or execution of this act on account of race or color,” he wrote. The law failed, however, because Southern bureaucrats frequently failed to inform blacks of their exclusive right to file land claims, the land was often of poor quality, and impoverished black settlers generally had little to invest in their homesteads. The program registered fewer than 4,500 homestead claims before the law was repealed in 1876.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]Impoverished black settlers had little to invest in their homesteads[/quote]

By the end of the Civil War, the federal government controlled 850,000 acres that had been confiscated from Rebel Southerners under wartime provisions. Nearly half the acreage was located in the Sherman Reservation, where thousands of freedmen had claimed 40-acre plots along the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida. Thousands more lived on leased properties at Norfolk, New Bern, and Roanoke Island.

For a time, writes historian Douglas Egerton, “It appeared that federal policy was about to enable the birth of a black landowning class.” Freedmen shared an almost universal belief that they had a right to the lands they had been working, many for several years. “Our wives, our children, our husbands, has been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now locates upon,” argued Bayley Wyat, a freedman living in northern Virginia. But, Egerton continues, it was simply too “baffling and revolutionary” an idea that “those who had produced the region’s wealth should now benefit from it.”

Following the Civil War, public discussions about compensating former slave owners far outnumbered those about compensating former slaves. A proposal that slaves freed by the Emancipation Proclamation be paid for labor after January 1, 1863, fell on deaf ears. The Johnson administration’s decision to return the confiscated land quickly disabused freedmen of any notion that they might be rewarded for their wartime loyalty, as demonstrated by the valiant service of more than 180,000 black troops and the work of thousands more on Southern plantations under the Yankee army’s control.

Within a year of the war’s end, the Freedmen’s Bureau had returned more than 400,000 acres to their antebellum owners. By the middle of 1867, all but 75,000 acres were in the hands of their original owners. Few decisions have had a more long-lasting and deleterious impact on American society than the Johnson administration’s decision to force the freedmen off confiscated lands. “Could the nation have been induced to listen to those stalwart Republicans, Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner,” Frederick Douglass lamented in 1880, “some of the evils which we now suffer would have been averted. The negro would not today be on his knees…supplicating the old master class to give him leave to toil….[And] he would not now be swindled out of his hard earnings.”

Rick Beard, an independent historian, author, and museum consultant, writes from Harrisburg, Pa.