Steely Civil War vet braved ice, altitude, and treachery to reach an unreachable summit

AFTER EIGHT HOURS hours in the black-and-white world above Mount Rainier’s tree line, where even in August all about was snow and rock, Hazard Stevens stared down into the crevasse separating him from the mountain’s 14,410-foot summit. Twenty feet across, immeasurably deep, the chasm gleamed emerald green all the way down.

It was high summer, 1870. In recent decades, mountaineers had summited Baker, Hood, Shasta, and every other volcano punctuating the Cascade Range from the Canadian border to Northern California—except the tallest: Rainier. The seismic giant had humbled half a dozen climbers. All were more experienced than Stevens, who to this point had ascended nothing higher than the bloodied rolling hills of Petersburg, Virginia, during the Civil War.

Nine days and 90 miles of slogging toward the fifth highest peak in the continental United States had brought Stevens, 28, and his companion, Philemon Beecher Van Trump, 31, to an impasse. With the sun sinking, the wind bitter, and their coats thousands of feet below, the men wrapped themselves in outdated American flags they had packed to plant when they had achieved the peak and contemplated the gap between the summit and themselves. Hazard Stevens reached for his coil of rope and fashioned a noose.

Stevens would have seen what he called “the leviathan of mountains” for the first time in December 1854, upon arriving in Olympia, Washington, with his mother, Margaret, and three younger sisters. The five had traveled from Narragansett, Rhode Island, to meet

paterfamilias Isaac Ingalls Stevens. A decorated veteran of the Mexican War, the senior Stevens had come west months earlier to claim his reward for supporting Franklin Pierce’s successful presidential bid: governorship of the newly formed Washington Territory and an additional appointment as the region’s superintendent of Indian affairs. Olympia was the seat of government for the territory, a wild frontier stretching from the north shore of the Columbia River to the Canadian border, and from the Pacific coast to the Continental Divide.

Rainier, the most glaciated peak in the contiguous United States, stood 75 miles east of Olympia, the half-million-year-old progeny of lava from the western slope of the Cascades. Most days, the convergence of warm ocean air and cold mountain drafts shrouded the active volcano in a cap of elliptical clouds. In clear weather, the mountain’s snowy dome, adorned with three distinct peaks and a pair of craters formed 2,000 year ago in Rainier’s last significant eruption, was visible for more than 100 miles in any direction. Seeing the mountain from Puget Sound in 1792, English explorer George Vancouver had named it for his friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier. Most local Indians knew the stone mass as Takoma, by various spellings, meaning “mother of waters.” More than two dozen glaciers extended from the dome, carving the mountain’s iconic shape of broad ridges and deep snowy valleys and giving milky life, thanks to finely ground stone dust suspended in melt water, to six river systems feeding dense evergreen forests stretching miles in every direction.

Rainier’s virgin summit had long taunted would-be conquerors. The most promising route to a point from which to ascend was the bed of the Nisqually River, which flowed from a glacier by the same name and made a sharp turn west at the sawtooth Tatoosh Range that guarded Rainier’s southern flank. En route to the Puget Sound, the river passed the nearest road’s end at Yelm Prairie, some 30 miles east of Olympia.

Native Americans hunted mountain goats as high as Rainier’s snowline, but would go no farther, fearing an evil spirit said to rule over a lake

of fire at the summit. In 1833, Scottish doctor William Fraser Tolmie was the first white man to approach Rainier on foot. Tolmie, who had come searching for medicinal herbs, wrote in his journal that he had had to stop short of the mountain when he came to “inaccessible precipices.” In the decades since, topographers and engineers had made attempts at summiting Rainier. The most recent, Augustus Kautz, had come within 400 feet of the summit in July 1857 when nasty weather turned him back. The next year, hoping to build a wagon road across the Cascades, local pioneer James Longmire helped cut a crude trail from his home at Yelm Prairie to the foot of the Tatoosh Range, a craggy gateway to Rainier’s forested base.

In 1867, Stevens met Van Trump, who had learned to climb in the Rockies. They shared an ambition to summit Rainier; Van Trump

could have been speaking for them both when he described Stevens as “a young man of indomitable energy and push, on whom obstacles acted only as spurs to action.” Forest fires the summers of 1868 and 1869 forced them to postpone an attempt. In early August 1870, they traveled to Yelm Prairie to hire Longmire as a guide. As dusk fell, they stopped to admire the mountain, that day without its usual cloud cap. “Rainier loomed up directly in front in full view over the fringe of forest, and the declining sun lit up with a crimson glow the whole white mass, bringing out in bold relief every rugged, rocky outline,” Stevens wrote later in The Atlantic Monthly. “Our admiration was not so noisy as usual. Perhaps a little of dread mingled with it.”

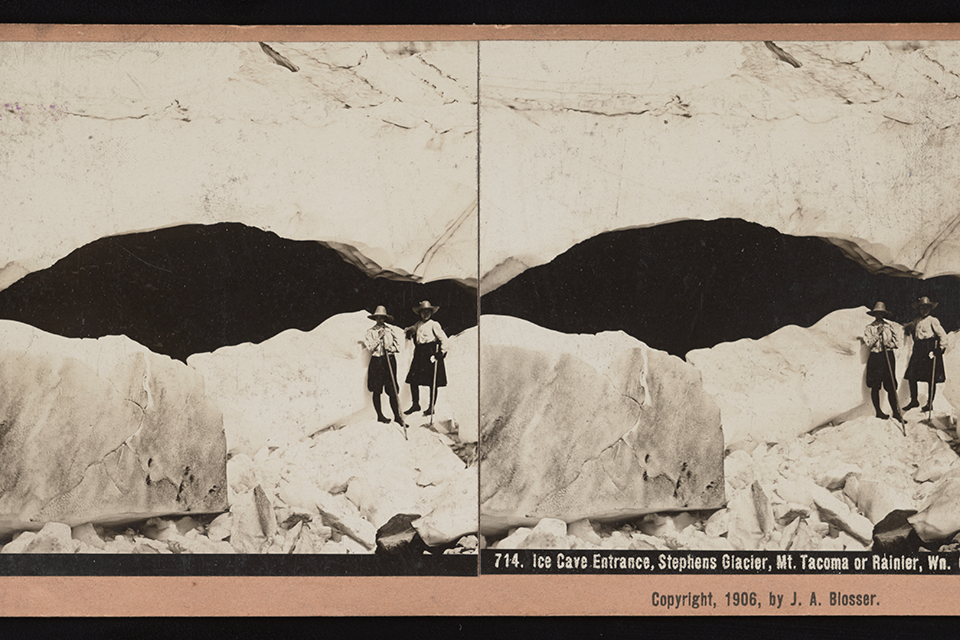

Stevens and Van Trump returned to Yelm on August 8 with Edmund T. Coleman, 46. Two years before, Coleman, an Englishman experienced at Swiss alpine ascents, had been among the first to scale 10,781-foot Mount Baker, 100 miles north of Rainier. Brimming with optimism, the three climbing partners carried a pair of flags—a 13-star revolutionary version, and a contemporary 32-star version—and a brass plate bearing their names, which they planned to plant at the summit. Longmire again bushwhacked his trail for more than 60 miles up the Nisqually, delivering the trio to Bear Prairie, where Rainier towered. “Startlingly near it looked to our eyes, accustomed to the restricted views and gloom of the forest,” Stevens wrote. The climbers hired a Yakama Indian guide, Sluiskin. Each was to pay Sluiskin $1 per day to supply fresh meat and convey them to Rainier’s permanent snowline, where the buckskin-clad guide would leave them to ascend the mountain. The Indian swore the best approach was to depart the Nisqually and cross the Tatoosh Range.

Coleman had been a bad choice—an over-packer who lagged and turned back before the first plateau, taking with him the party’s altimeter and bacon. Sluiskin set an eager pace, urging on Van Trump and Stevens for three days of hot, hard travel through forests of Douglas fir and Western hemlock. Van Trump wondered if the guide was taking them out of their way to pad his pay. Their destination was the base of a glacier just east of the Nisqually icefield. Recalling peaks projecting like needles from the valley floor, Stevens wrote, “It seemed incredible that any human foot could have followed the course we came.”

The next leg troubled Sluiskin. The Englishman’s fast fade had him doubting his other clients’ grit. Stevens and Van Trump convinced the

guide they were sincere, but still the Indian pleaded with them to turn back before they came within range of mudslides, crevasses, and killing cold—all the work of the mountain spirit, he said. When the white men insisted, Sluiskin said he would wait in camp for three days, then travel to Olympia to report their deaths. Stevens retired to his bedroll and drifted off to the rumble of avalanches and Sluiskin at fireside, chanting ominously.

Stevens first forged friendships with Native Americans on a nine-month trip he made at age 13 with his father, who had to negotiate treaties between the region’s tribes and the federal government. Governor Stevens’s methods of acquiring some 100,000 square miles of territory—including Rainier and environs, which became a federal reservation—later came under intense scrutiny, but his son long treasured their two-horse odyssey.

Camped by the Missouri River in the summer of 1855, the governor gave his son a long leash. Hazard, whose first name was his mother’s family name, became a fine horseman and an excellent shot. In October, the two were still on the road, tying up loose ends for the upcoming Blackfeet Council, at which nine tribes would rendezvous in north-central Montana to negotiate peace, hunting rights, and access for whites through the region. Needing to be sure a chief of the Gros Ventre tribe who lived on the Milk River would attend, the governor dispatched his son to find the Indian. The youth made the 150-mile round trip over wind-whipped yellow plains in 30 hours, and was thrilled to report that he had seen a grizzly bear.

On day nine of their climb, Stevens and Van Trump rose before dawn to prepare their packs. Scouting the summit the day before, they decided they could reach the peak and return in a day. Since leaving Yelm, they had been sweltering, so they left their coats and blankets, carrying enough food for a single meal, one large canteen, and only the most basic gear, like the alpine climbing staffs the men used to steady themselves.

The climbers needed three hours to reach 10,000 feet, at which the mountain became perilously steep. Ascending a rocky, angular ridge, Stevens and Van Trump came to a massive square outcropping left by glaciers. Clinging to the rock, they felt for footholds along a narrow

debris-covered saddle. As they shuffled, their boots loosened stones that clattered into the icy abyss.

After 400 yards, the ledge intersected a snowfield leading to the dome high above. As the men climbed a slick gutter where glacier met rock, boulders and ice thundered down. One struck the staff in Van Trump’s hand.

In late 1857, when his father’s term as governor expired, Hazard and the rest of the family moved east to Boston. In 1860, he entered Harvard College. When war broke out in 1861, his father assumed command of the 79th New York Highlander Volunteers. After freshman year, Hazard joined that unit. That September Isaac Stevens wrote to his wife to report proudly that he had appointed their 19-year-old his adjutant general. A year later, at the Battle of Chantilly, Virginia, Brigadier General Stevens was killed leading a charge; young Captain Stevens lay wounded on the same field.

Margaret Stevens begged her son to come home to help raise his sisters. Hazard rejoined the Army of the Potomac. He wrote almost daily to his mother, sending every dime of salary he could spare, along with the proceeds of bets he won racing on horseback. “Happy are they who die nobly on the battlefield, instead of disgracing their manhood by staying at home at a time like this,” he wrote his mother. He fought at Fredericksburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Petersburg, and elsewhere. During the siege of Suffolk, Virginia, on April 19, 1863, he led a charge under heavy fire across the Nansemond River to capture a fort. “I have seen so much of life that I can take mighty good care of myself,” he wrote home.

Van Trump’s stick disappeared, caroming into Nisqually Glacier. To keep from joining the wayward staff, the men climbed onto the snowfield and took turns hacking steps with an ice axe. The arduous process brought them to the crevasse, on whose far side an ice pinnacle rose about 12 feet.

Trusting in hemp, frozen water, and his knot-tying skills, Stevens lassoed the ice spike. Tightening the noose and swinging on the rope, he and Van Trump each crossed to the far wall and clambered hand over hand to solid ground. The mountain’s southwest peak was in sight but thin air forced them to rest often as they crept in a violent wind from the snowfield to a 10-foot wide ledge poking from the main cone. At the highest point, which they named Peak Success, they fastened a flag to Stevens’s staff and stood, shouting in triumph. “And weak cheers they seemed, for at that lonely height there was nothing to echo or prolong the sound,” Van Trump said later. “The wind was now a perfect tempest, and bitterly cold; smoke and mist were flying about the base of the mountain, half hiding, half revealing its gigantic outlines; and the whole scene was sublimely awful,” Stevens wrote.

That flag-planting celebration had been premature. About a mile to the northeast the true summit rose about 250 feet higher. The men followed the rim of a snow-filled depression to what they called Crater Peak. The sun was setting; they would have to overnight in place. Van Trump noticed steam issuing from a crack along the crater’s rim. Edging into the opening, Stevens and Van Trump entered a cave, its ceiling

four feet in spots, with a smooth rock bottom and a roof of ice. Steam from deep in the crater had formed the chamber; the source was a steam vent about 40 feet into the cave. Devouring their scant meal and emptying the canteen, they piled stones around the vent. There they lay, each wondering if he was going to make it.

Stevens spent New Year’s Eve 1865 waiting out a snowstorm in New York Harbor aboard the steamer Henry Chauncey, bound for the Pacific Northwest. Three months before, he had left the 79th Volunteers as their youngest brigadier general, declining a regular army commission. Bureaucratic fumbles had disrupted his late father’s pension payments, putting his mother and sisters in dire financial straits. In Washington Territory, Stevens, 23, hoped his military reputation and his father’s connections would make up for his lack of a trade.

Within months Stevens was working for the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, collecting fees charged freighters and fares from passengers at the Columbia river town of Wallula, Washington. Wallula was by Stevens’ lights a “dreary place,” but he had as companions a pair of setters that loved hunting prairie chickens as much as he did. It took him a year to save enough money to bring his mother and the girls back out West.

In 1868, Stevens landed an appointment as U.S. collector of internal revenue for the territory. The family returned to Olympia’s maple-lined streets. Inspecting distilleries and supervising regional deputies kept Stevens constantly on horseback, galloping among settlements in Rainier’s long shadows. In his spare hours, he studied law under Elwood Evans, one of the territory’s first attorneys and a former aide to his father. He passed the bar exam in 1870.

Secure in their cave—though their clothes were sweat-drenched on one side and frozen on the other—the mountaineers woke nauseated from sulphur in the steam. Outside the wind was up, and the sky dark with storm clouds. Stevens scratched Coleman’s name from their brass plate and returned to Crater Peak, wedging the memento and the canteen in a cracked boulder. He and Van Trump, seeing the third, lower peak from a distance, named it Takoma before reversing their path toward camp, 8,000 feet below.

Near the end of their long descent, Van Trump slipped, sliding 40 icy feet before loose rocks stopped him, in the process gashing his thigh. A few hours later, the two men hobbled into their empty camp. They were famished, but Sluiskin was out hunting. Stevens prepared a meal of marmot so offensive that Van Trump observed, “I don’t think the General had taken an elaborate course in domestic science.” When Sluiskin returned, he at first thought he was seeing ghosts, then praised Stevens and Van Trump as “strong men with brave hearts.” In the

morning, the trio began trekking out, at Stevens’s insistence following the Nisqually River basin. This route cut their time by a third, heightening Van Trump’s suspicions that Sluiskin had taken the Tatoosh route out of greed. “It was a specimen of aboriginal graft,” he wrote. At Bear Prairie they found Coleman, well-fed and in jolly spirits. The white men bid adieu to Sluiskin and after waiting out a three-day rainstorm, returned to Yelm.

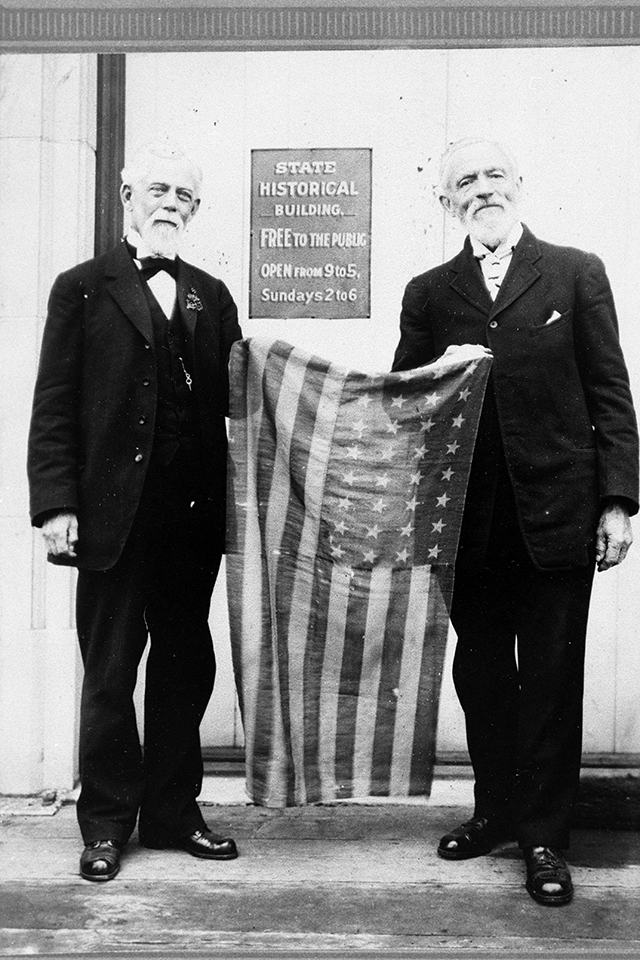

Stevens and Van Trump arrived in Olympia a few days later by way of the Longmires’ horse-drawn carry-all, their summit flags flying from the carriage. Lean and sun-scorched from the 240-mile journey, Stevens likened himself and his buddy to “veterans returning from an arduous and glorious campaign.”

Given the mountain’s reputation and their relative lack of experience, not everyone believed their extraordinary feat. However, two months later, when a second party sought the Rainier summit, its members found the crevasse-crossing rope hanging where Stevens had left it. On subsequent ascents, Stevens and Van Trump would search for their plaque and canteen, but never find them.

The government hired Van Trump as the first ranger in what in 1899 would become Mount Rainier National Park. By 1900, more than 100 people had summited Rainier. A professional guide service established in 1905 brought those ranks to multiple hundreds. Van Trump remained at the center of a debate over the mountain’s name, arguing passionately and in vain for preservation of the Indian appellation, Takoma.

Stevens’s unexcused 17-day absence cost him his job as a federal revenue collector. He had his law license to fall back on, and went to work for the Northern Pacific Railway, chasing timber thieves. In 1874 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him commissioner to investigate remaining British claims on the San Juan Islands, an archipelago on the Canadian border that had been awarded to the United States through international arbitration.

In 1875, the Stevens family again moved to Boston. Hazard Stevens opened a law practice and flirted with politics. In 1894, the U.S. Army awarded him the Medal of Honor for valor at Suffolk. Denied a generalship at the outbreak of the Spanish War, he published The Life of Isaac Ingalls Stevens, a passionate 1,000-page defense of his father’s legacy, in 1901. Stevens never married. Still smitten with Rainier, he returned to Washington in 1916, living in Olympia. On October 11, 1918, less than two months after climbing to his base camp on Rainier at 76, the conqueror of the highest peak in the Cascades died.

He had fallen down the stairs of his farmhouse.

_____

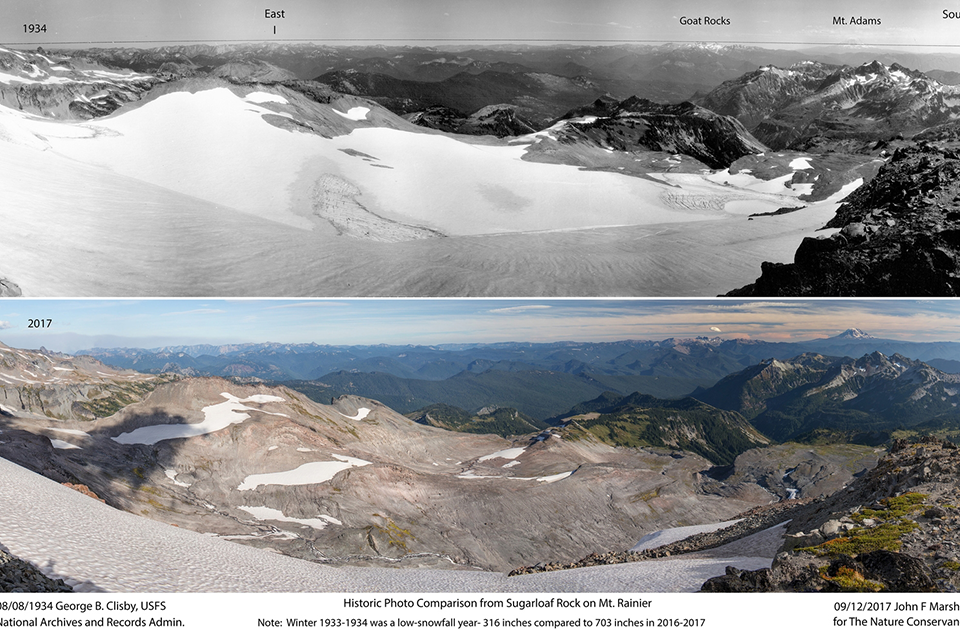

Melting Away

The white-capped world into which Hazard Stevens and Philemon Beecher Van Trump clambered is disappearing. Ice cloaked the Cascade Range long before Mount Rainier’s volcanic cone rose 500,000 years ago. Although Rainier remains the most glaciated American peak outside Alaska, in the last 50 years its ice fields have shrunk at least 14 percent.

Four have disappeared.

Many scientists blame global warming. Since 1895 the average Pacific Northwest temperature has risen 1.4° Fahrenheit. Forecasting is difficult in regions where mountain and ocean weather systems collide, but digital models predict that this century will see temperatures continue to climb, with more precipitation taking the form of rain instead of snow.

This scenario spells trouble for Rainier’s 26 named glaciers, formed in prehistory when heavy snowpack in the high, frozen reaches of the mountain compressed into slow-moving rivers of ice. When a glacial system is in balance, each winter new ice accumulates, keeping pace with losses incurred through summer melting at the system’s foot. At Rainier, this is no longer happening. Between 1970 and 2008, only two of the peak’s glaciers gained volume. For a decade, the Nisqually Glacier, on which Van Trump lost his climbing staff, has been shrinking in length an average 140 feet annually. The Paradise-Stevens Glacier, which feeds the waterfall that raged beside the first summiteers’ base camp, has lost well over half of its mass and now comprises two stagnant ice fields.

Glacial melting is a part of normal climate variation; Rainier’s glaciers have fluctuated in size for millennia. Thirty-five thousand years ago, the now four-mile long Cowlitz Glacier stretched 60 miles to the mountain’s southeast. What’s troubling today is the speed of melting—estimated at six times the historic rate—and the consequent dwindling of a vital regional water source.

Ecologists and engineers cringe at the long view. As temperatures rise and glaciers recede, so do the alpine and sub-alpine habitats of signature Rainier residents like pink mountain heather, a ground cover, and the shrill-whistling pika, a small herbivore. Accelerated run-off is dumping disproportionate amounts of debris—boulders, gravel, and silt glaciers scraped from the mountain as they creep—into the five major river systems that Rainier’s ice fields feed.

As a result, river beds are rising; today’s Nisqually flows some 40 feet higher than in 1910. Other streams are rerouting themselves, sometimes through trails, roads, and campgrounds. The National Park Service has built dikes and levees to protect key infrastructure and the settlement of Longmire, now 29 feet below the Nisqually. A major flood, like one in 2006 that did $36 million in damage and closed the park for six months, easily could overwhelm these locales, threatening access for the 1.7 million people lured to the park annually by Rainier’s ever-changing charms. —Jessica Wambach Brown