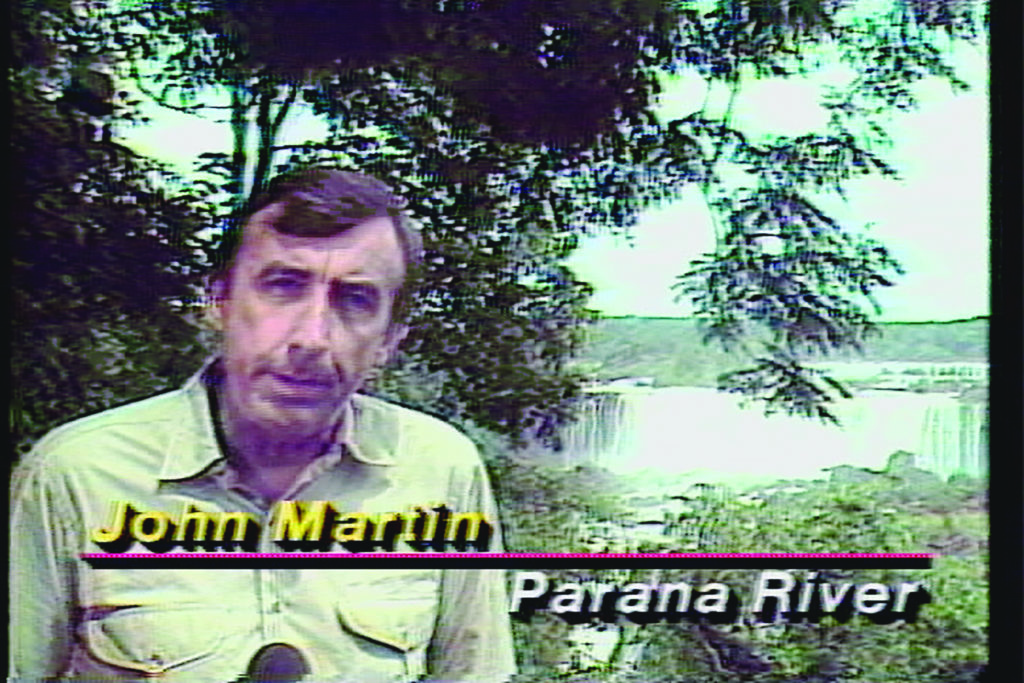

Former ABC News correspondent John Martin recalls his search for the most notorious Nazi to evade capture after the war.

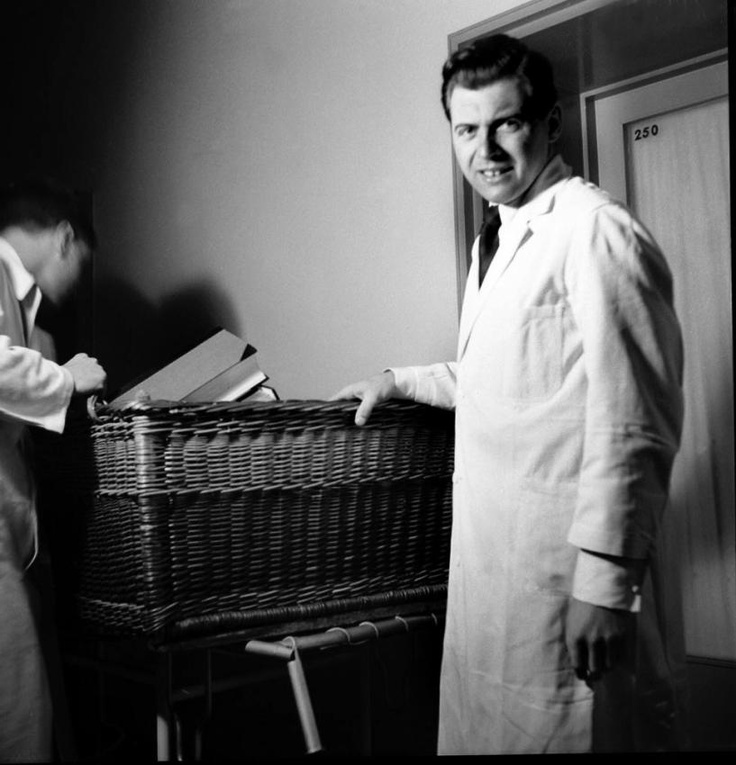

JOSEF MENGELE frequently assumed an enthusiastic posture on the railroad platform at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp as trainloads of captives arrived from across German-occupied Europe. Pointing in one direction, the SS physician—nicknamed the “Angel of Death”—sent the healthiest prisoners to factory work as slave laborers; pointing in the opposite direction, he sent countless women, children, the frail, and the elderly to die in gas chambers.

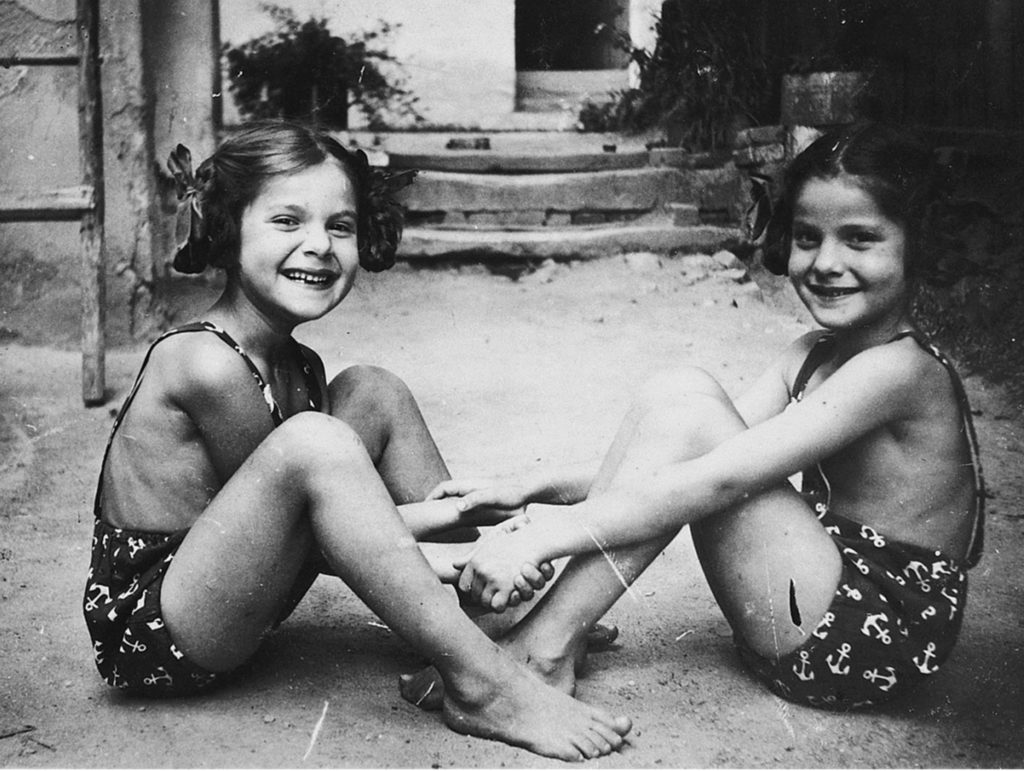

A third group, primarily twin children, were delivered to well-supplied barracks where Mengele conducted grisly and often fatal surgical experiments in a pseudo-scientific quest for the secrets of genetics.

In January 1945, as the Soviet army approached Poland from the east, Mengele fled. American soldiers arrested him in Weiden, Germany, more than 400 miles west of Auschwitz, and held him for two months in two prisoner camps. But the Americans released Mengele when they failed to identify him as the same Josef Mengele listed on “wanted” circulars compiled by the United Nations War Crimes Commission and the Allied High Command in France. With luck and assistance from a network of friends in Germany, he evaded recapture.

Four years later, according to the most authoritative account, Gerald L. Posner and John Ware’s 1986 book, Mengele: The Complete Story, the fugitive doctor used forged identity papers to slip away from a farm in Rosenheim, about 120 miles southeast of his family’s hometown of Günzburg, and escape to Argentina. Mengele was spotted numerous times in South America but always melted away before he could be apprehended.

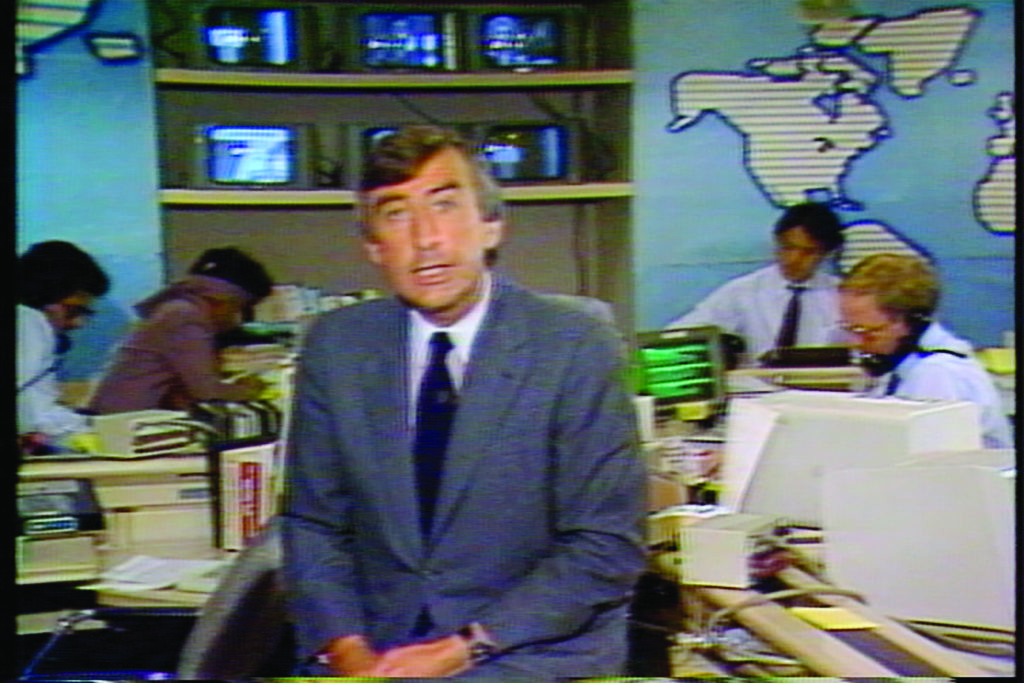

With the capture of wanted Nazis Adolf Eichmann in Argentina in 1960 and Klaus Barbie in Bolivia in 1983, Mengele’s name rose to the top of any list of the most notorious war criminals still on the loose. In 1985, 40 years after the end of World War II, I found myself assigned to the search for Mengele. Here’s how it began.

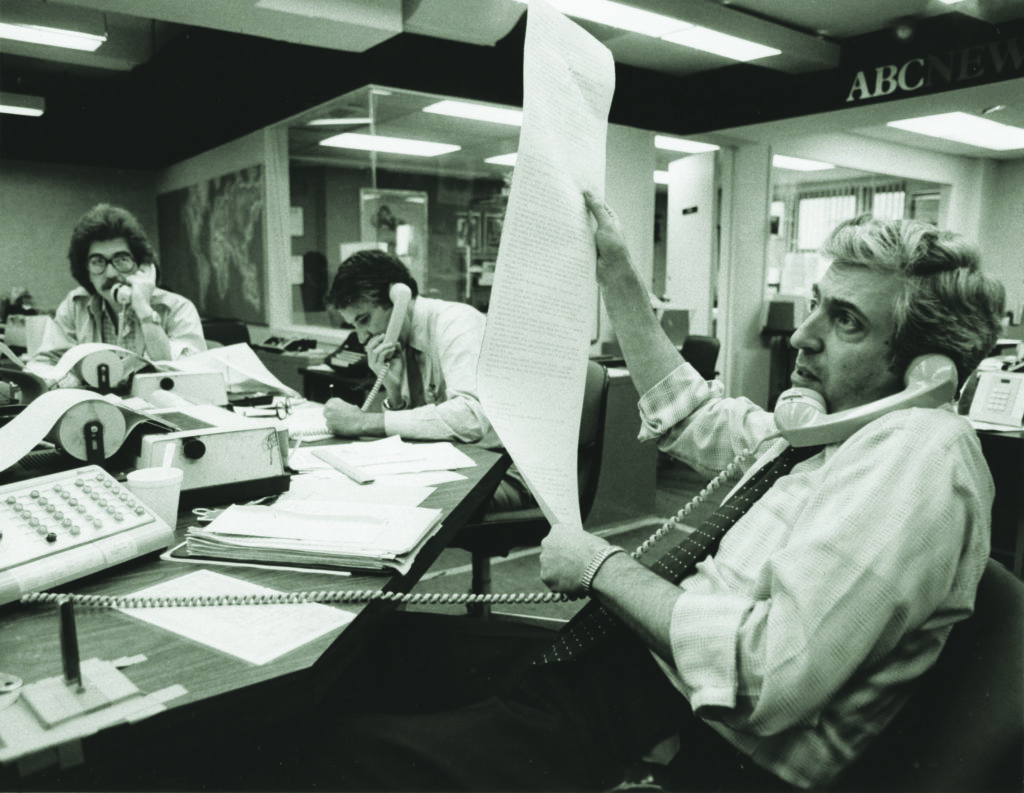

LATE ONE MORNING in February 1985, the phone rang in my office at ABC News in Washington, D.C. “Herr Martin,” said a voice, “I want you to find Josef Mengele.”

“Who is this?” I said, and then tried to answer my own question: “Walter, is that you?”

It was Walter Porges, the affable, gray-haired foreign editor of ABC News, calling from his office in New York. [Note: World War II senior editor Larry Porges is Porges’s son.]

“How much time do I have?” I joked. “He’s been missing for, what, 40 years? Do you need this for tonight?”

“No,” he said, a smile in his voice, “but soon. I’m going to help you.”

“That’s great,” I said, “but where the hell do we start?”

“We’re going to Vienna; we’ll get Simon Wiesenthal to help us.”

On the face of it, Porges had a brilliant idea. He and Wiesenthal had much in common.

Wiesenthal, a Jew born in Ukraine, had been taken prisoner as a slave laborer and survived at least three concentration camps. Now living in Vienna, Austria, he was the best-known Nazi hunter of the day, a tireless agitator for the capture and punishment of Adolf Hitler’s murderous henchmen.

Porges, also Jewish, had fled from Vienna to Great Britain in early 1939 as a seven-year-old boy, one of about 10,000 children evacuated by train from Nazi territory on the Kindertransport. At the end of the war, he had emigrated to New York. Having risen through the ranks, he was now directing foreign coverage for one of the world’s most aggressive television news organizations.

Working with Wiesenthal, it seemed, meant we could almost certainly track down this most notorious Nazi war criminal.

On March 6, Porges and I flew to Vienna and checked into the Hotel Imperial, a converted 19th-century Italian Neo-Renaissance palace. As a young man, Hitler was said to have worked at the Imperial as a day laborer. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, he slept in the hotel as a feared and honored guest.

As we settled into our rooms, I began to realize how much the assignment meant to Porges. He was returning to the scene of a monstrous crime that had upended his life and decimated his family. By the time Porges and his older sister, Lisl, fled Vienna, Nazi gangs were attacking Jews openly and 91 of the city’s synagogues had been destroyed.

But on the day we visited Wiesenthal in his modest office in Vienna, we suffered a shock.

“I won’t help you,” said Wiesenthal. “Why should I help you?” Porges was stunned. “Because we want to find him as badly as you do,” he responded.

“If I tell you where Mengele is,” Wiesenthal said, “he will find out you are looking for him and get away.”

Wiesenthal’s stiff-armed rejection of our help was puzzling. In numerous interviews, he had claimed that he knew from his sources that Mengele was living in South America. He talked at times of a jungle estate surrounded by barbed wire and protected by guards, insisting that Mengele was the evil beneficiary of corrupt, high-ranking political patrons.

It turns out Wiesenthal’s certainty was a charade of sorts, designed to focus attention on the lack of effort being expended by prosecutors. In fact, Wiesenthal had no idea where Mengele was hiding, which he admitted a year later in a letter to Gerald Posner, a resourceful American lawyer and author who tracked down leads throughout my search and who was once the pro-bono attorney for sets of twins who survived Mengele’s brutal attention at Auschwitz: “I often gave information which I could not check to the press, only so that Mengele’s name would not be forgotten,” Wiesenthal wrote.

Porges was stymied. “I guess you’re on your own,” he said to me as we left the office. “I’ll help every way I can with crews, but the rest is up to you.” Disappointed and angry, he flew back to New York.

Staying behind in Vienna with both a camera crew and a producer, 33-year-old Scott Willis, I began to feel panicky, uncertain where to turn, not comfortable plunging into uncharted waters. Searching for a monster like Mengele felt noble, but scary. What if Wiesenthal was right about a protected compound? Getting past guards packing machine guns sounded like a remarkably dangerous path to exposing his hiding place.

FIRST OF ALL, where were we to look? Nobody seemed to know with any certainty. Everyone, it seemed, had a hunch or a theory of where this Nazi criminal was hiding, but not much in the way of evidence.

Since I was already in Vienna, I decided to start there and speak with victims who had known Mengele firsthand. Hermann Langbein, head of an Auschwitz survivors’ committee, pointed me toward the family of Ernst Kohn, a deceased Auschwitz survivor who had helped track Mengele’s movements in South America. In a house on a small side street, one of Kohn’s surviving relatives told me Kohn was convinced that Mengele had fled from Argentina to Paraguay.

Assuming I was heading to South America, I wanted to talk to people who had searched there for him and Adolf Eichmann, the cold-blooded administrator upon whose authority the Nazis exterminated 6,000,000 Jews in what the Germans called the “Final Solution.”

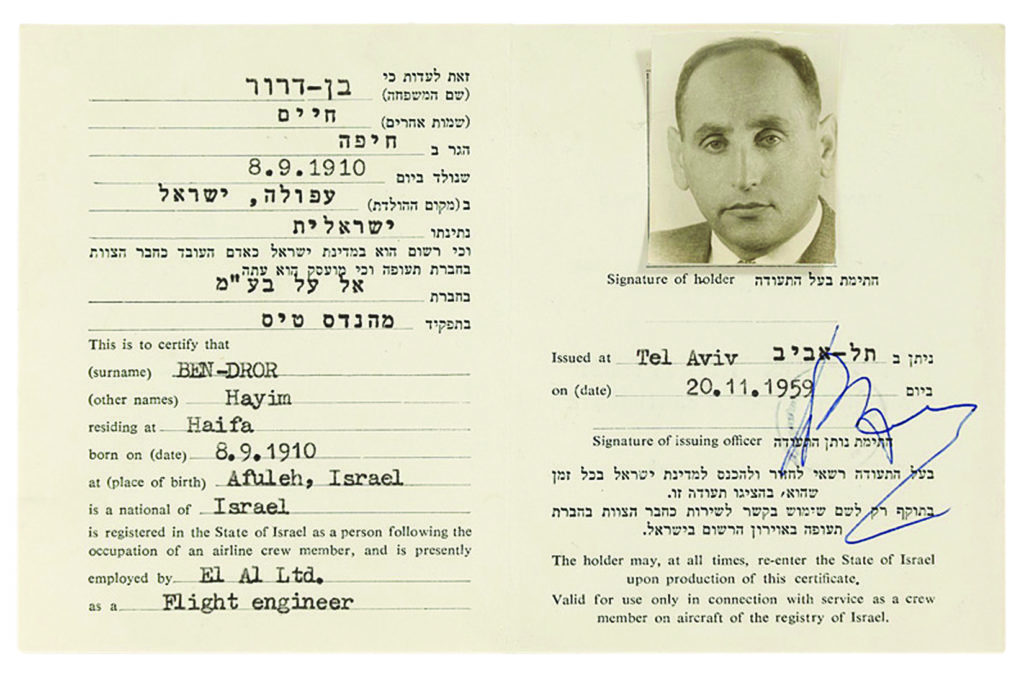

Willis booked us a flight to Tel Aviv, where he called an ABC News radio correspondent who knew Isser Harel, the retired head of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency. An interview was swiftly arranged.

Mossad had tried to capture Mengele at the same time their agents abducted Eichmann in Argentina in 1960, Harel told me as we sat in a garden at his home in Tel Aviv. But they were too late—Mengele had moved to Paraguay in 1959, nearly 12 months earlier. In 1962, at about the time of Eichmann’s execution, the Israelis resumed their hunt for Mengele.

“I think we detected his hiding places,” Harel said, squinting in the afternoon sunlight in an interview that aired on Nightline. “We had very reliable information that Mengele was in this place, in this estate.”

Soon Mossad agents were preparing for an operation in the countryside of Paraguay. But the Israelis were unable to confirm Mengele’s exact position, and the raid was scuttled. The local population was wary of outsiders and, Harel surmised, likely sounded the alarm the moment any foreigners appeared. “And he was also guarded with people,” he added.

“Let me understand,” I said. “Your men did see him, but they could not…”

“No, we didn’t see him,” Harel said.

“Not even once?”

“Not even once.”

Weeks later, in Paraguay, I would learn from Alejandro von Eckstein, a former Paraguayan military officer, that Harel’s suspicions were correct: Mengele had been tipped off.

“I was told that five Israelis had come here searching for Mengele,” he said in Spanish as we sat with a translator in his modest home office in Asunción. “We told him he should be very careful.”

“So the government warned him that the Israelis were looking for him?” I asked.

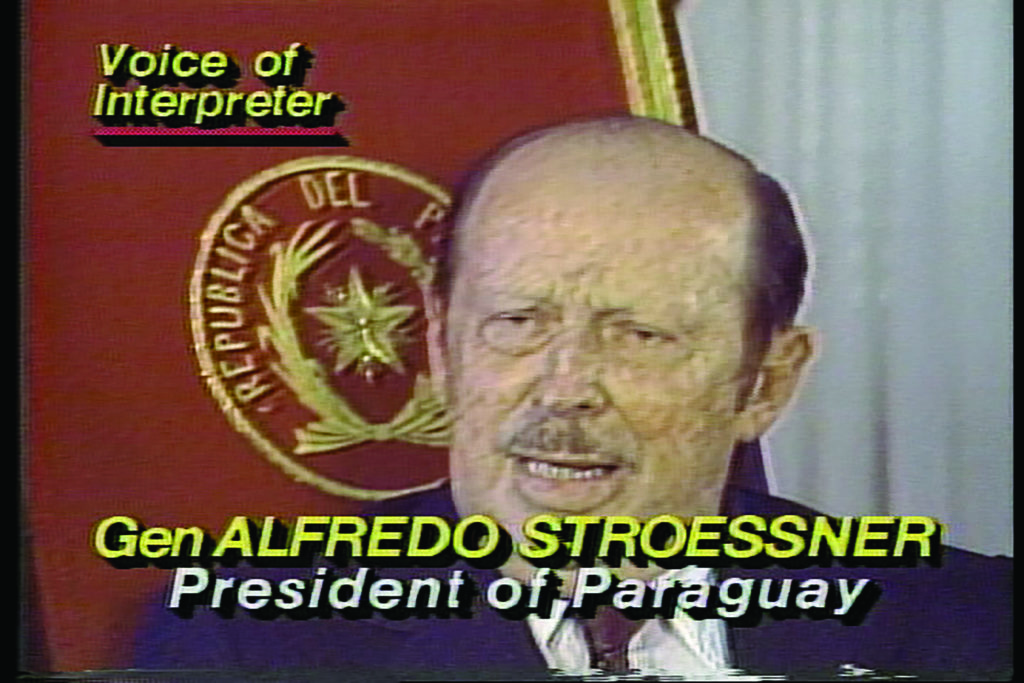

Von Eckstein, resplendent in a white military officer’s jacket with gold epaulets and braided cuffs, answered: “Oh, surely, surely, they warned him.” One possible reason for this pro-German sentiment: the president of Paraguay, dictator Alfredo Stroessner, was himself the son of an immigrant German army officer.

In the meantime, as Scott Willis and I flew back to Europe from Israel, I felt gloom settling over me. If Harel’s Mossad couldn’t find Mengele with its highly trained agents, what made me think I could track him down?

In Paris, I met with Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, whose recently published memoir, Hunting the Truth, is an account of their relentless efforts to find and expose Nazi fugitives across the world. “To locate him,” Beate Klarsfeld told me, “I think the most important thing is to work on the spot where he is.” Insisting Mengele was alive in Paraguay, she said, “[Paraguay’s leaders] know where he is, and they know his whereabouts, how to find him, where to find him.”

AS I PONDERED Klarsfeld’s information, I realized there was one unexplored avenue left in Europe—but it was a daunting task. Mengele’s family still lived in Günzburg, West Germany. If I could find a way to interview them, perhaps I could shake loose a clue to where he could be found.

Günzburg is a small Bavarian town about 75 miles northwest of Munich. In the years immediately following World War II, its largest enterprise, the Mengele farm equipment company, had grown into a well-known international manufacturer.

Hal Walker, a fellow ABC News correspondent, had suggested trying to interview the Mengeles a month earlier. He had traveled to Günzburg in the wake of mounting interest in the story; the U.S. Congress had just passed a resolution demanding that Paraguay find and arrest Mengele in preparation for trial. Seeking townspeople to interview, Walker had become friendly with Rudolf Köppler, the town’s young mayor.

“If you get to Günzburg,” Walker told me by telephone from London, “look up Rudy Köppler; he’s a good guy.” According to Walker, Köppler’s parents had been persecuted by the Nazis in Berlin during World War II.

When Willis and I arrived in Günzburg, I called Köppler and gratefully accepted an invitation to dinner at his home. As the evening was ending, I leaned forward and asked: “Is there a way you can help me talk to the Mengeles?” Köppler smiled. “Of course. I’ll call Dieter in the morning.” The next afternoon I found myself seated in the boardroom at Karl Mengele & Sons. Across the table from me sat Dieter Mengele, the company’s largest stockholder and co-chief executive with Karl-Heinz Mengele, his brother, who was said to be unavailable.

Staring down at us from above Mengele’s head were oil portraits of the company’s three main founders and operators: Karl Mengele and two of his sons, Alois and Karl Jr., all of whom had passed away. Nowhere in the wood-paneled room, of course, was there an image or plaque mentioning the third son—Dieter and Karl-Heinz’s uncle Josef, the family’s black sheep.

“I don’t know if he’s in Paraguay or not,” said Dieter, a nervous hesitation in his voice, “or if he was in Paraguay—he probably was in Paraguay.” Then he added: “I have no idea.”

I didn’t believe a word he was saying. Working in a craft that values skepticism, I could not suspend my disbelief, a kind of mental callus built up over my years as a reporter.

“Do you think he has survived?” I said, hoping he might be ready to unburden himself of the secret.

“I think he’s dead.”

“Why do you think that?” I said with suspicion, leaning back.

“There are so many people looking for him,” he said, then paused. “I don’t think if they—if it’s true what I’m reading, everybody’s looking after him—I think they would have found him if he’s still alive.”

Later, undoubtedly sensing my continuing disbelief, Dieter returned to the question of his uncle’s survival: “I really must say once more, I think he’s dead,” he said. “If people want to believe this or not, that is my feeling.”

But earlier on in the interview Dieter had also said, ‘’I would like to talk to him, too, you know.” This comment compounded my confusion: was he lying or hinting at the truth?

Whatever else, this was a worldwide scoop. In the 40 years and two months since his uncle had fled Auschwitz, Dieter was the first Mengele family member to speak to a journalist about the Angel of Death. Dozens of reporters had trod the same path to their door and come away empty-handed. I had three videotape cassettes of the interview and images; the story was broadcast on ABC’s World News Tonight with Peter Jennings on March 18, 1985.

WITH NO NEW CLUES, there seemed no place else to look but South America. Based on prevailing wisdom (not always a sound basis for action), Paraguay was the obvious choice.

As we flew from Miami to Asunción, Frank Manitzas, an ABC News producer, fell into an intense, low-volume discussion with his seatmate, a middle-aged man in a business suit and tie. Sitting across the aisle, I couldn’t make out their words. When I asked, Manitzas only said that we were switching hotels when we arrived in the capital. Once in a taxi, however, Manitzas explained in a whisper that his seatmate had turned out to be a silent business partner of President Stroessner. Our new hotel, he said, smiling, was secretly owned by Stroessner.

Within days, an interview with the president was arranged. In the 26 years since Mengele’s arrival from Argentina, I was told, this was Stroessner’s first public discussion with a reporter regarding the fugitive’s presence in his country.

At first, it seemed to lead nowhere.

Speaking in his office in front of two Paraguayan network television cameras and an ABC News camera, Stroessner denied any personal knowledge of Mengele’s residence at any time.

“I will be very sincere,” Stroessner said, “I don’t know where he is, and we cannot find out where he is.”

This seemed blatantly untrue, based on a series of sightings reported over the years. Listening to Stroessner from my chair five feet away, I again fought my skepticism.

“I have received no information personally nor did I ever know him,” he said.

“You never met him when he was here?” I said.

“No, absolutely not.”

“So, if I understand you correctly, Mr. President, Dr. Mengele is not here. But do you have any information when he was here last?”

“No, I would not know, and that is what I have been telling you,” the president said, his voice rising. “We have given you all the explanations,” he added impatiently.

Moments later, I repeated a question regarding reports that Mengele had been sheltered and shielded in Paraguay. Stroessner exploded. I had been speaking to him, he sputtered, as if he were a defendant being cross-examined in a court of law.

As I had with Dieter Mengele, I felt lied to and stonewalled. But I was also offered—and ignored—a major clue to one of the biggest stories of my life. This time it was uttered in the final moments of our conversation. It came after the cameras were capped.

“Frankly,” Stroessner said in halting English, “Mengele was here, but he left, sometime in the 1960s.” “Where did he go?” I asked. “I am not certain,” he said, “but I believe he went to Brazil.”

ABC News aired the Stroessner interview on May 10, 1985. In it, I did not report Stroessner’s mention of Mengele’s flight to Brazil. My skepticism had overwhelmed me.

WITH PRESSURE from American news coverage intensifying—CBS and, to a lesser degree, NBC, had joined ABC in covering the story—the search for Josef Mengele reached a turning point that very same day, 6,600 miles away in Europe. Israeli, American, and West German investigators met in Frankfurt, and the three countries pledged a renewed commitment to find the Angel of Death. Once the meeting ended, West German investigators belatedly connected three clues that had been collecting dust in their files.

One clue was a tip in late 1984 from Serge and Beate Klarsfeld that Mengele’s son, Rolf, had traveled to Brazil in 1977 on a false passport. In their memoir, the Klarsfelds said they learned of the trip from a Berlin associate, a neighbor of Rolf’s, who secretly entered his apartment and found the passport.

The second clue was a letter sent from a German living in Paraguay to a neo-Nazi prison inmate in West Germany serving time for bomb attacks on immigrants. Intercepted by prison officials, the missive described an “uncle” who had died on a Brazilian beach. Suspecting the letter was referencing Mengele, German investigators contacted Brazilian authorities—but the lead was dropped when the Brazilians were unable to pinpoint the incident.

A German university professor provided the third clue when he reported that a Mengele factory supervisor, Hans Sedlmeier, had confided to him that he had secretly funneled modest amounts of money to the fugitive for many years.

Amid a rising worldwide clamor, on May 31, 1985, the prosecutors obtained a search warrant and raided Sedlmeier’s house in Günzburg. There they discovered more documents pointing toward Mengele having gone to Brazil.

Brazilian investigators then questioned several Mengele friends in São Paulo and its suburbs, who grudgingly revealed the truth—that, six years earlier, on February 7, 1979, just off a sunny Brazilian beach, the man who had sent tens of thousands of men, women, and children to their deaths at Auschwitz and brutally experimented on hundreds of helpless twin children had suffered a stroke while swimming and drowned.

A few days later, on June 6, Brazilian authorities dug up a body, believed to be Mengele’s with an assumed name, from a grave in a small town outside São Paulo. I called Gerald Posner in New York and asked him to meet me in Miami, where we boarded a flight to São Paulo.

We arrived at night, just in time to sit in a television studio and answer questions on-air about the case from Ted Koppel, my boss from the earliest days of Nightline. I counseled caution about accepting the report that Mengele had drowned in 1979. “They’re not sure yet, Ted,” I said. “They need to examine these bones very carefully before deciding.” The conclusion sounded accurate, but the proof had to come from the body.

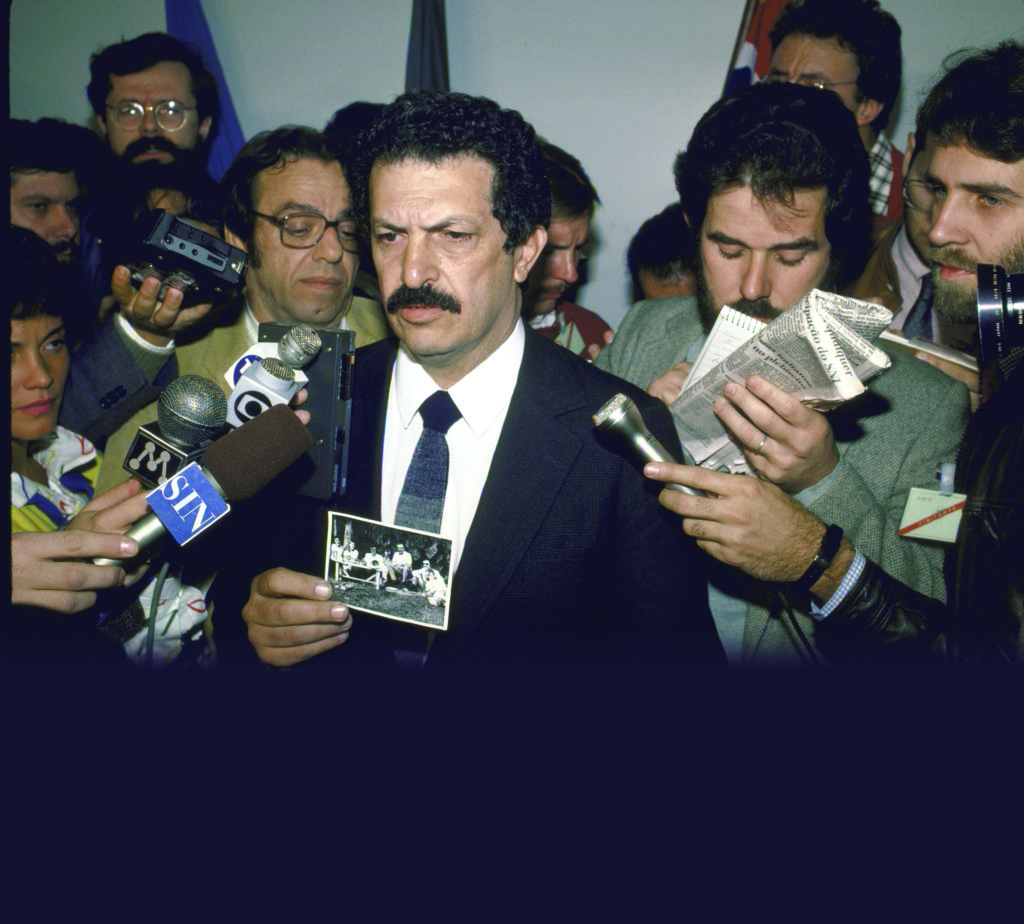

Two weeks later, that proof came. Romeu Tuma, the chief of police in São Paulo, held a news conference and declared that the exhumed body belonged to Mengele.

As the news conference ended, I turned to Lowell Levine, an American scientist brought to Brazil to work on the skull as a forensic odontologist—one of dozens of experts assembled for the task.

“Is there any doubt at all, Dr. Levine, that this is Josef Mengele?”

“Absolutely not,” said Levine.

Josef Mengele was dead. After all the stonewalling and all the misdirections, I felt an acute sense of relief. Mengele had been unmasked and his victims had been resurrected, however briefly, from the grave of failed memory. In an unexpected way, Walter Porges and I had accomplished our mission.

ODDLY, despite our shared effort to find Mengele, to the best of my memory, Porges and I never discussed the case again. To his credit, his efforts had reenergized the search. In 19 weeks, we produced 21 stories from six countries based on dozens of interviews conducted over more than 34,000 miles of travel.

In the end, we were tracking a ghost.

Was it worth the effort? Without question. It’s true that Mengele’s earlier capture and punishment would have given tens of thousands of surviving Jews and their families a sense of vindication and closure. And the world would have been exposed to Mengele’s horrific acts as an unforgettable example of what must never be countenanced by neglect.

But even four decades after World War II ended, there was still a clear message in 1985: the horrors inflicted by this Nazi doctor had not been forgotten nor dismissed as acceptable wartime behavior.

Today, four decades after his death, this is a lesson for the new generations born since World War II. By uncovering his death in hiding, we prevented Josef Mengele from escaping history. ✯

This story was originally published in the October 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.