In December 1944, at the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, a truck rumbled down a road in Belgium, carrying a group of soldiers who called themselves the Wolf Pack. Despite the name, they weren’t fierce fighters being sent into combat. Their mission was to make music to entertain the troops.

The band’s leader, a private named Dave Brubeck, had just turned 24. Already an accomplished pianist who reveled in experimentation, he would go on to become one of the most famous jazz musicians, bandleaders, and composers of all time.

But Brubeck’s brash, unorthodox style as a musician obscured an inner turmoil. Though he wanted to serve his country, Brubeck quietly loathed the violence of war. “I resolved never to have a cartridge in my gun if I ever landed at the front,” he told an interviewer years later. “I wanted to be sure beforehand that I could never kill a man.”

Brubeck wasn’t yet the creative genius who would produce Time Out, the first jazz album ever to sell a million copies (in 1959), but his prodigious talent had already caused an officer to pluck him from an assignment as a replacement soldier in the 140th Infantry Regiment of General George Patton’s Third Army and make him an entertainer. Even so, Brubeck couldn’t completely escape the war raging around him.

Brubeck’s commanding officer had sent the band on tour, performing for GIs as they ate their chow. At one stop, a plane flew overhead as the musicians were setting up in a clearing where GIs were waiting in line for their food. “One of the GIs shouted, ‘Hey! That’s a German plane, and he’ll be coming back,’ ” Brubeck later remembered. Everybody ran from the clearing to take cover, and Brubeck and his musicians hastily climbed into their truck and drove away. They weren’t sure where to go. “There were no maps of this section with us,” Brubeck said. “We chose the road that seemed the most traveled.” By then it was getting dark, but the driver kept the headlights off. The truck rolled up to a soldier directing traffic. He flashed a dim light over the truck and waved it through.

“As we passed him, I realized that he was wearing a German helmet,” Brubeck said. Brubeck told his driver to go over the next hill, turn around, and then race back down the road at full speed before the German had a chance to discover that he’d mistakenly let an American truck through.

A few miles later at a checkpoint manned by American soldiers, the group encountered a bigger problem. As Brubeck wrote in an essay for Time magazine in 2004, the sentries didn’t believe that a truck full of musicians would be driving around in the darkness. One of the guards came up to the truck, and Brubeck noticed that he had a grenade in each hand, with the pins pulled. He tensely explained to Brubeck that his buddies had just been killed by Germans who were driving a captured American truck. “All of them could speak perfect English, just like you’re speaking,” the soldier told him.

After a few disquieting seconds, the soldier examined Brubeck’s papers and then asked him for the password for that area. “The guys in the back were all praying that I knew it,” Brubeck would later write. Fortunately, he did, and they were allowed to pass.

That brush with death would change Brubeck forever. He realized that if he lived through the war, he couldn’t be just another musician. Someday, he explained, “I would write music about peace and the brotherhood of man.”

Brubeck grew up in California’s Central Valley, where his father was a rancher and his mother a piano teacher. Brubeck started to play the piano at age four, but his experimentation began almost as soon as he started touching the keys. He didn’t like taking lessons, instead preferring to improvise his own pieces. When his family moved into a ranch house near Ione, southeast of Sacramento, the ranch hands would gather in the evenings and listen to the young Brubeck play cowboy songs, sometimes with his father accompanying him on the harmonica.

Brubeck’s mother, realizing early on that her son had a unique talent, taught him differently from her other students. “She didn’t force me to practice, and she didn’t force me to play serious music, but she gave me a lot of theory, ear training, harmony,” he told the jazz magazine Downbeat in 1957. “From the time I was very small, it was impossible to make me play any of the classical pieces except when I’d sit down and play them by ear.”

Brubeck also learned to rope cattle and take care of other ranch chores. Aiming for a career in which he could help his father’s cattle business, he enrolled at the College of the Pacific in Stockton, intent on becoming a veterinarian.

After a year, though, Brubeck switched his major to music. He moved into a basement apartment where he and his roommates could jam around the clock without disturbing anyone and soon began playing jazz piano in local nightclubs and on a weekly campus radio show. The broadcast gave him a chance to meet and court the show’s co-director, an aspiring actress and writer named Iola Marie Whitlock, who soon became his wife.

World War II preempted Brubeck’s education and musical ambitions. In 1942 he was drafted into the U.S. Army, and though he felt incapable of firing a shot in anger, he knew that the army also might give him a chance to play music instead of fight.

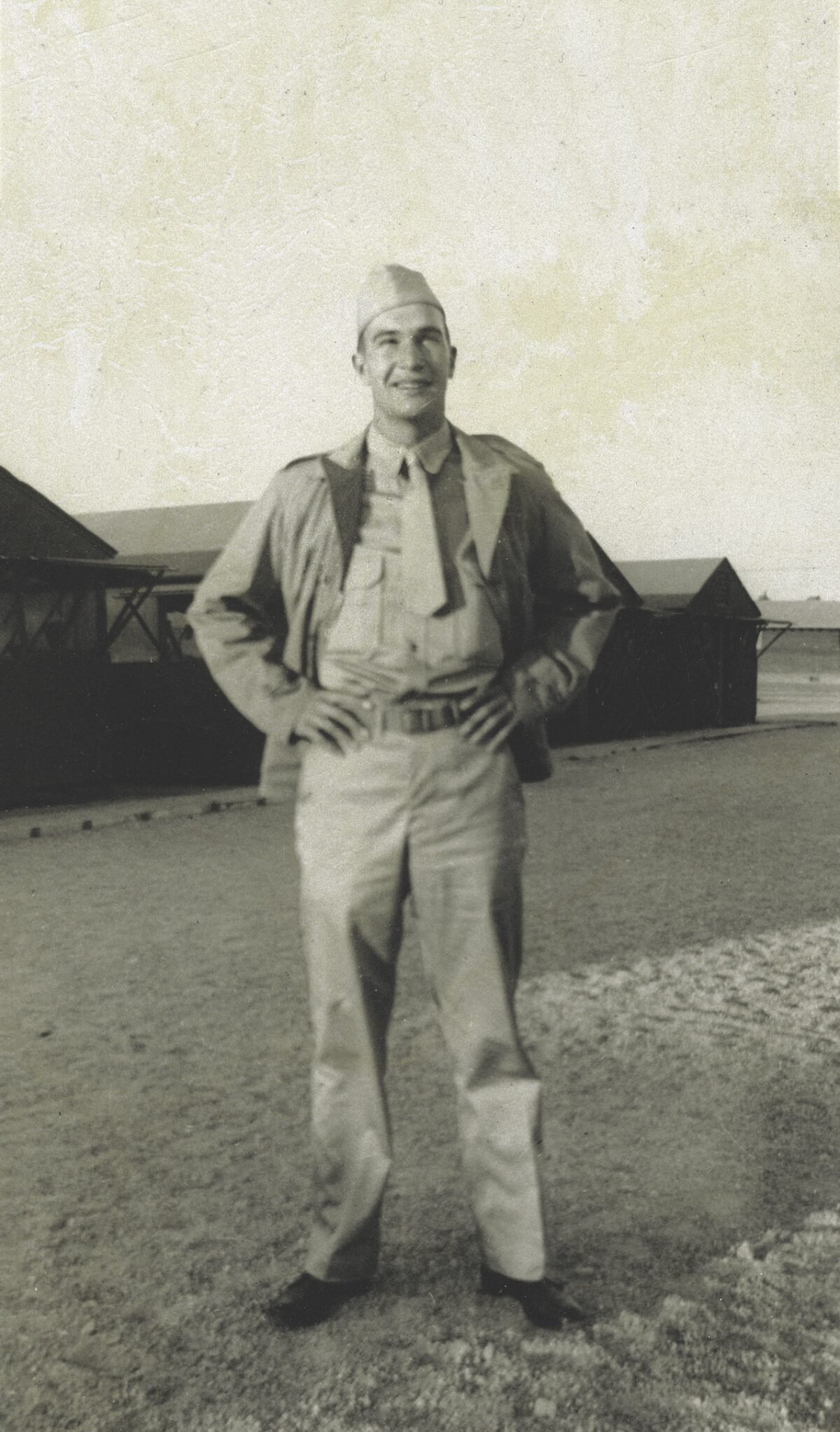

Brubeck was first sent to Camp Haan, east of Los Angeles. It was the first time he had ever been to southern California, and for a boy who’d grown up on a ranch in the Central Valley, it was probably a bit of a culture shock. But Camp Haan had several bands, filled mostly with soldiers who had been musicians in Hollywood. It was three weeks before Brubeck even got a chance to play with them. But when the 21-year-old finally did sit down at the piano, listeners on the base were startled.

“All the guys in these bands were wonderful musicians and very competent, but I was shocking everyone,” Brubeck would tell Downbeat. “They just completely wigged over me there were so many new ideas.”

Some of his arrangements were so wild, in fact, that his fellow soldiers refused to play them. He took one big-band composition, “Prayer of the Conquered,” to Stan Kenton in Los Angeles and wangled a chance to play it for him. “Where did you ever hear chords like this?” Brubeck recalled Kenton saying. Kenton liked the piece enough to try rehearsing it with an orchestra, but he ultimately decided that it was a little too avant-garde. He told Brubeck that he should bring it back to him in 10 years.

For the rest of the year and a half that Brubeck spent at Camp Haan, he switched to writing small-combo arrangements, some of which presaged his postwar work with his own group. But once again, his work was a bit too avant-garde for all but “the furthest-out jazzmen in the band,” he recalled years later.

With D-Day approaching, the band had to dissolve, and Brubeck learned he would be sent overseas as a rifleman. In his remaining time stateside, Brubeck headed back to the Presidio in San Francisco, where a friend arranged for him to audition for an army band based there. “It was my last chance, I thought, to avoid the infantry, which I was now in, and get back into a band,” he explained in a 1991 interview. The audition didn’t go well. Asked to play some blues, Brubeck responded by playing in two different keys—“probably G in this hand and B flat in the other hand, which was a device I was using a lot, I think before anybody in jazz,” he later recalled.

He didn’t get the gig. But he did make an impression on one of the band members, saxophonist Paul Desmond, who after the war would become his friend and musical collaborator—and the composer of “Take Five,” the 1959 Dave Brubeck Quartet song that would become one of the most popular, instantly recognizable jazz pieces ever.

Brubeck shipped out with the infantry on the SS George Washington, and after a brief stop in England arrived in France in the fall of 1944, three months after D-Day. Carrying the rifle he had resolved not to load, he was sent as a replacement to the front near Metz, where Patton was beginning a hard-fought siege against a fortress city held by the Germans. “It was just about the worst possible place to be, because the Germans were really wiping them out,” Brubeck later told Downbeat.

At the last depot along the route, Brubeck caught what for him was an incredibly lucky break. He learned that a Red Cross–sponsored show needed a pianist, and he volunteered to play. Two officers took note of his performance. One of them, Colonel Leslie Brown, decided that somebody as talented as Brubeck shouldn’t be sent into combat. That suited one of Brown’s subordinates, Captain Leroy Pearlman, who staged shows to entertain the troops. He wanted to put together a small band and recruited Brubeck to join it. Brubeck thought that may have saved his life, as he later told Stars & Stripes: The company in which he would have served “got pretty messed up a couple of days later.”

Pearlman had a trick for protecting Brubeck and the other 18 musician-soldiers that he recruited for the assignment, as he told the story to Studs Terkel for Terkel’s 1984 book The Good War: An Oral History of World War II. He simply pulled their paperwork, so that in the eyes of the military bureaucracy, they just disappeared. “They stayed alive, and I had a band,” Pearlman said.

Pearlman’s trick worked so well that at one point the army actually sent Brubeck’s wife a telegram, asking if she knew of his whereabouts. “If you don’t know, I’m sure I don’t,” Iola wired back. “She got a couple of letters back marked ‘deceased in action’ before it got cleared up,” Brubeck told Stars & Stripes years later.

Meanwhile, despite being only a private first class, Brubeck served as bandleader for the Wolf Pack, a hastily assembled group that toured the war zone in a truck. Brubeck’s band was stationed at a replacement depot, “so soldiers were coming through to be sent to the front,” Brubeck recalled in a 2006 oral-history interview. “If they’d say they were musicians, they’d send them over to me, and then that’s the way I formed the band.”

In the days when the U.S. armed forces were still segregated, the multiracial Wolf Pack stood out. With Brown’s support, Brubeck chose a Black soldier, Gil White, to serve as his master of ceremonies, and brought in Jonathan Richard “Dick” Flowers, a Black trombonist, as well.

Getting the necessary musical talent was just one of many challenges Brubeck’s ensemble faced. Brubeck had to barter for musical instruments and come up with a repertoire that would entertain the soldiers. He managed to avoid playing military music, instead doing jazz versions of popular songs and occasionally slipping in his own compositions, some even inspired by the war.

In March 1945, with the war in Europe clearly ending, Brubeck stood one day and watched trucks and tanks lumber across a pontoon bridge that the army had erected at Remagen. The sight of the bridgehead inspired him to compose a piece, “We Crossed the Rhine,” in which he tried to capture the rhythms of the vehicles.

Three days after the German surrender, Brubeck and his band rolled into Munich, where they got to play a jazz show in an actual concert hall. After that, he and his ensemble continued to tour liberated France and Germany for a few more months, joining in USO tours.

In an effort to put aside the hard feelings from the war, he sometimes recruited German musicians to play with his band. “I found then—and I’ve found since—that there’s a great friendship in musical life,” he explained to Stars & Stripes. “Musicians understand each other through their love of music. We should all be musicians.”

Discharged in 1946, Brubeck returned to the United States. He decided to use his GI Bill benefits to finish his studies at Mills College in Oakland, California, where he became a pupil of Darius Milhaud, a Jewish composer who had fled his native France in 1940, shortly after the Germans occupied it. At the time, Brubeck was feeling discouraged about the resistance that he had encountered to his musical experimentation.

“To be honest, I was going to give up jazz because of all the hassle I had had, even in the army, to get the musicians to play my stuff,” he told Downbeat. “And I recalled even Kenton thought I was too far out. So I figured jazz wouldn’t be the place to present the ideas I wanted to.” Instead, Brubeck thought of becoming a contemporary classical musical composer, writing oratorios and cantatas for orchestras and vocalists. But Milhaud convinced Brubeck to stick with jazz, counseling him that every great composer had expressed the culture that he was familiar with, and that jazz was the quintessential American art form.

When Brubeck began performing again in San Francisco, he was a man possessed, more daring and experimental than ever. “My only explanation was that I was playing out the war through improvisation,” he recalled years later. “And it was pretty wild at that time, because I’d been through Europe and seen all the destruction there.”

Brubeck’s fame grew, as did his record sales. By the mid-1950s, Time was championing him as “probably the most exciting new jazz artist at work today.” He achieved such renown, in fact, that in the early years of the Cold War the U.S. State Department appointed him a cultural ambassador and sent him on tours of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. And in the 1960s, millions of Americans became familiar with “Take Five” as the theme of NBC’s Today Show.

Although Brubeck achieved his greatest fame in jazz, he eventually returned to his vision of composing modern classical music with themes of peace and brotherhood, including The Light in the Wilderness and The Commandments. He also performed during the Reagan-Gorbachev summit meeting in 1988, when the two leaders grappled with how to reduce the threat of nuclear war.

But Brubeck’s wartime experience continued to affect him profoundly. Years later he still grieved for army friends who had fallen in battles that were mostly long forgotten. Brubeck, who died in 2012 at age 91, saw his music as a way of coping with their loss. “It gives you a sense of, ‘Why am I here? Why did they get killed?’ ” he once told an interviewer. “And then also you say to yourself, ‘I’m alive and I’m gonna do as much as I can.’ ”

Patrick J. Kiger is an award-winning journalist who has written for GQ, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Urban Land, and other publications.

This article appears in the Spring 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | A Hep Cat in Patton’s Army