In many respects Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart’s military escapades played out like fiction. With action in three major wars, numerous battle in- juries and multiple plane crashes on the one-eyed, one-handed war hero’s service record, it seems that receiving a Victoria Cross was but a footnote to his military career, as he failed to mention it in his memoir, Happy Odyssey.

The Belgian-born aristocrat craved a life on the edge from a young age. In 1899, at age 19, Carton de Wiart left college to serve in the Second Boer War. Though underage by a year, he enlisted in the British army as Trooper Carton and claimed to be 25. While serving in South Africa with Paget’s Horse, he received bullet wounds to his stomach and groin—the first of nearly a dozen grievous injuries he suffered during his career. After recuperating, he accepted a commission in the 2nd Imperial Light Horse and ultimately finished out the war a lieutenant in the 4th Dragoons.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914 Carton de Wiart was en route to suppress an uprising in British Somaliland. Though eager to take part in the action in Europe, he dutifully served with the Somaliland Camel Corps, battling the Dervishes led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, the “Mad Mullah.” During a mid-November attack on a Dervish blockhouse Carton de Wiart was shot in one arm and twice in the face, losing part of an ear and his left eye. For his actions he received the Distinguished Service Order.

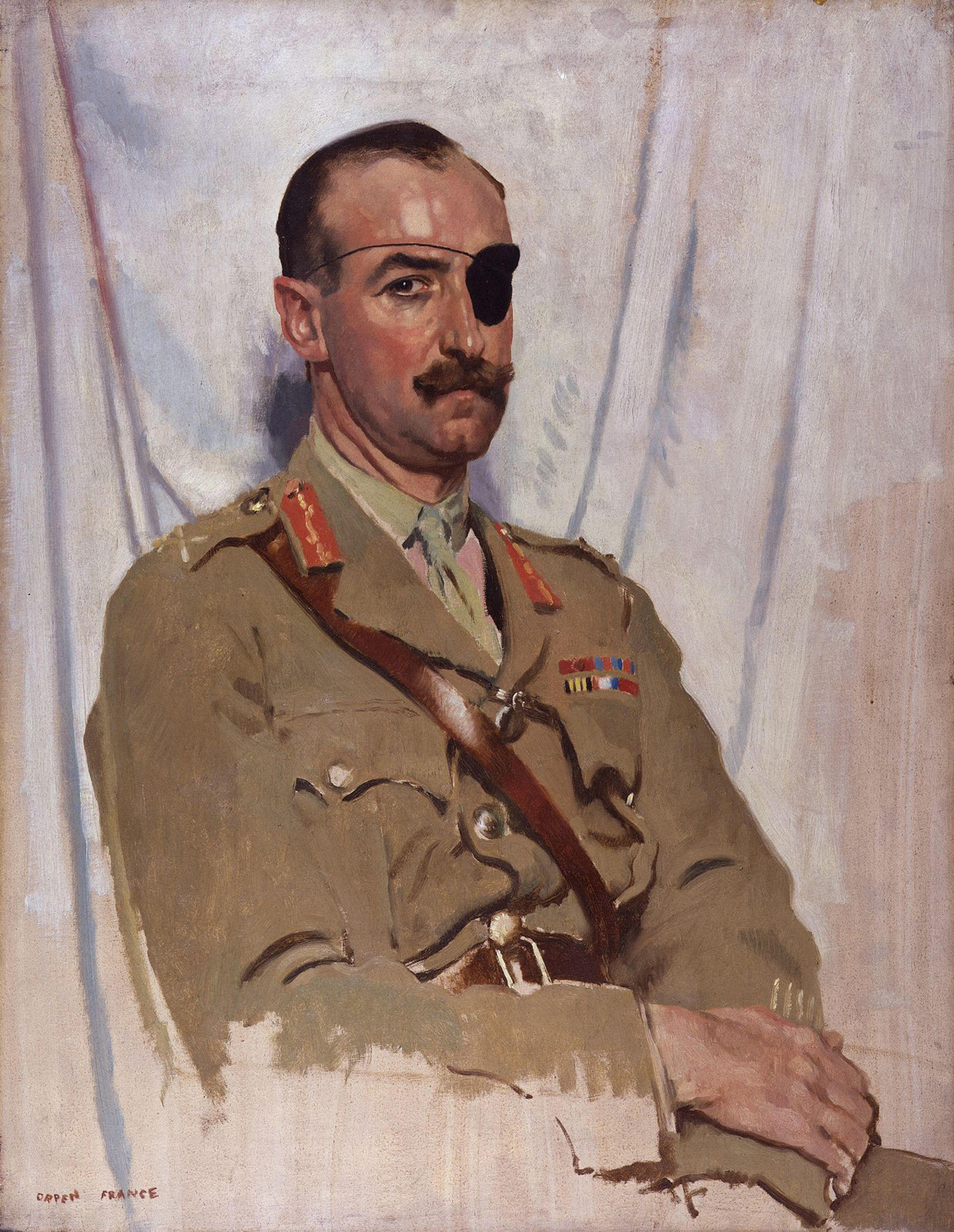

After convalescing in England, Carton de Wiart wore a “startling, excessively uncomfortable” glass eye long enough to convince a medical board he was fit to fight, then threw the eye from a taxi and adopted his trademark eye patch. In spring 1915 he was sent to the Western Front near Ypres with the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards. The first night, as his regiment was relieving an infantry unit, the Germans launched an artillery barrage. Carton de Wiart’s left hand was mangled when his shattered watch splintered into his wrist. When a doctor refused to amputate two dangling fingers, Carton de Wiart yanked them off himself to relieve the pain. Later that year a surgeon removed the hand.

Despite his disabilities Carton de Wiart again persuaded a medical board in early 1916 to certify him for general service. Attached to the infantry, he soon took command of the 8th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment. In July, at the Battle of the Somme, the 8th was supporting a unit ordered to capture La Boisselle, one of the strongest German positions. After three commanders fell in action, Carton de Wiart took control and drove through the German line to help capture the city. He led by example, pulling grenade pins with his teeth and throwing them with his one hand. He received the Victoria Cross “for most conspicuous bravery, coolness and determination during severe operations of a prolonged nature.” His citation noted: “He frequently exposed himself in the organization of positions and of supplies, passing unflinchingly through fire barrage of the most intense nature. His gallantry was inspiring to all.”

By war’s end Carton de Wiart had incurred many more injuries, but he always returned to the front. Combat suited him. “Frankly, I had enjoyed the war,” he wrote in his memoir.

Carton de Wiart spent the interwar years with the British Military Mission in Poland—when that country was fighting simultaneous wars with the Germans, Soviets, Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Czechs—surviving an ambush by Cossacks and two plane crashes. He was aide-decamp to the Polish king and settled in Poland in 1921.

Peace didn’t last long. In 1939 the Germans invaded Poland, pulling Carton de Wiart back into the British army and into another world war. Promoted to major general, he led campaigns in Norway and Yugoslavia before falling into Italian hands in 1941. On Carton de Wiart’s release in 1943, Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed him a diplomatic representative to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, the position from which Carton de Wiart retired in 1947. He eventually settled in Ireland and died at home in 1963 at the ripe old age of 83.

Originally published in the January 2015 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.