Private William Othniel Taylor gazed numbly across the Little Bighorn battlefield on the morning of June 28, 1876, three days after he and fellow troopers of the 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, had charged into a large Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment on the banks of the Montana Territory river. Taylor and comrades had been pinned down by the enemy for 36 hours with limited water before being saved by relief forces that brought astonishing news: Custer and his entire command had been annihilated.

“Our errand now was to seek our comrades who had died with Custer and pay our last respects by a scant and hasty burial,” Taylor recalled. “The most that could be done was to cover the remains with some branches of sagebrush and scatter a little earth on top, enough to cover their nakedness, a covering that would remain but a few hours at the most when the wind and rain would undo our work and the wolves, whose mournful and ominous howls we had already heard, would scatter their bones over the surrounding ground.” Standing on that desolate ridge, Taylor could never have imagined how those shallow graves would soon mark a very different type of battleground—one on which various factions exploited the dead in skirmishes over class warfare, politics and legacy.

Each year upward of 240,000 people make a pilgrimage to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Grave markers scattered across its grounds carry different meanings for different people. The site has also generated an estimated $14 million a year in tourist dollars, thanks largely to one iconic name: Custer. Yet, the morbid allure of the Little Bighorn dead is not an uncommon phenomenon. The graves of such legendary Western figures as Geronimo, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Sitting Bull, Quanah Parker and Wild Bill Hickok have all been disturbed in one way or another—some by relic hunters and grave robbers, others in the wake of lawsuits and public squabbles over whose bones actually lay beneath a particular headstone.

The graves of such legendary Western figures as Geronimo, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Sitting Bull, Quanah Parker and Wild Bill Hickok have all been disturbed in one way or another—some by relic hunters and grave robbers, others in the wake of lawsuits and public squabbles over whose bones actually lay beneath a particular headstone

Americans’ enduring fascination with the West is the root of this collective narrative. Long ago the American West was a faraway place of surreal landscapes that stoked the imagination. Beyond the Mississippi and across the wide Missouri early explorers and pioneers discovered oceans of prairie grass, the majestic Rocky Mountains, the expansive Grand Canyon and a yet unspoiled California boasting gold-filled streams and soaring redwoods. Wild and untamed, the land invited rhapsodic language. Pioneers like Mary Austin Holley—a cousin of Texas colonist Stephen F. Austin and among the first Anglo visitors to that region—groped for the words to describe the grandeur they found. “One’s feelings in Texas are unique and original and very like a dream or youthful vision realized,” Holley gushed in an 1833 memoir. “Here, as in Eden, man feels alone with the God of nature and seems, in a peculiar manner, to enjoy the rich bounties of Heaven in common with all created things.” In Texas, she marveled, the “sun and the air seemed brighter and softer than elsewhere.”

Such embellishments were infectious. Yet countless descriptions sprang from truthful if incredible eyewitness accounts. Lieutenant John Williams Gunnison, a surveyor with the Corps of Topographical Engineers, learned that firsthand after an encounter with mountain man Jim Bridger (see related feature, P. 68). “With a buffalo skin and piece of charcoal,” Gunnison recalled, “[Bridger] will map out any portion of this immense region and delineate mountains, streams and the circular valleys called ‘holes’ with wonderful accuracy.” The lieutenant related Bridger’s sensational—and, it turns out, reasonably accurate—description of what would become Yellowstone National Park:

He gives a picture most romantic and enticing of the headwaters of the Yellowstone. A lake [Yellowstone] 60 miles long, cold and pellucid, lies embosomed amid high precipitous mountains. On the west side is a sloping plain several miles wide, with clumps of trees and groves of pine. The ground resounds to the tread of horses. Geysers spout up 70 feet high, with a terrific hissing noise, at regular intervals. Waterfalls are sparkling, leaping and thundering down the precipices and collect in the pool below

The [Yellowstone] river issues from this lake and for 15 miles roars through the perpendicular canyon at the outlet. In this section are the Great Springs [Mammoth Hot Springs], so hot that meat is readily cooked in them, and as they descend on the successive terraces, afford at length delightful baths.

Few believed Bridger. Regardless, Americans remained captivated by stories of the magnificent wilderness beyond the bounds of civilization. The West presented a grand stage for Eastern audiences, a stage that necessarily called for larger-than-life actors. In that aspect, too, the region delivered in abundance. The cast of Westerners proved diverse, from dashing generals (Custer) to unflinching gunslingers (Hickok), “righteous” outlaws (the Kid and James), “hostile” Indians (Geronimo and Sitting Bull) and “noble savages” (Quanah Parker). Where the storyline sometimes strayed, yellow journalists and dime novel hacks stood ready to deliver a lively narrative blended with myth and reality.

Dime novelist Ned Buntline was prototypical of this propaganda machine. He wrote yarns about Army scout William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody—“founded entirely on fact”—and drew on incidents from Wild Bill Hickok’s life to flesh out a villain named “Jake M’Kandlas.” Buntline eventually killed off the character at the hands of two Texas women, prompting Hickok to complain tongue in cheek in an 1873 letter to a newspaper, “Ned Buntline of the New York Weekly has been trying to murder me with his pen for years.” The end for the real Wild Bill came on Aug. 2, 1876, when he was shot down in a Deadwood, Dakota Territory, saloon—a salacious demise that spawned still more pulp fiction.

Hack writers pounced on Billy the Kid’s 1881 shooting death with equal enthusiasm and shameless greed to publish new Western sagas. News of the Kid’s demise had barely reached the East Coast when dime novelist John Woodruff Lewis dashed off a sensational “True Life of Billy the Kid,” under the pseudonym Don Jenardo, for The Five Cent Wide Awake Library, a New York–based blood-and-thunder publication with nationwide distribution. More than a dozen dime novels soon followed, although the Kid’s legacy didn’t need any padding. He was a bona fide legend well before his violent end. Editors of Eastern newspapers, keenly aware of readers’ insatiable appetite for sensational frontier happenings, had routinely published stories of his exploits.

Custer, Sitting Bull and Geronimo were also living legends by the time they were lowered into their respective graves. As with the Kid, the world would most remember Custer for his final act—a sensational death. Massacre of our troops, trumpeted one New York Times headline in the wake of the Little Bighorn. Custer and Seventeen Commissioned Officers Butchered. General William Tecumseh Sherman perhaps best expressed the nation’s stunned disbelief when he stated, “I don’t believe it, and I don’t want to believe it, if I can help it.” The image of “wild hordes” of Indians descending on Civil War hero Custer and his bluecoats surely toyed with the American psyche.

In the aftermath of the June 1876 battle Sitting Bull was cast firmly in the role of villain, at least by observers in “civilized America.” Though he’d provided pivotal spiritual inspiration for Lakota warriors that day, the story of his life and eventual violent death was left to the mercy of prejudiced journalists.

Yet not even Sitting Bull could surpass Geronimo in fame—or infamy—on the Western frontier. The Chiricahua Apache’s mystique arguably soared higher in death than it did in life—an admirable feat given his reputation as a prolific warrior who for years, with a handful of fellow holdouts, eluded thousands of U.S. and Mexican troops in the rugged mountains of Arizona, New Mexico, Chihuahua and Sonora. When he surrendered for the final time on Sept. 3, 1886, Americans kept abreast of the drama in Eastern newspapers breathed a collective sigh of relief. Geronimo suffered an ignominious postscript, dying on Feb. 17, 1909, of pneumonia after having lain overnight in a puddle of water following a drunken fall from his horse. He died a prisoner of war at Fort Sill, Okla.

Death often ushered in renewed interest in such frontier icons

Death often ushered in renewed interest in such frontier icons. The subsequent exploitation of their graves occurred in different forms at different times. Those shameful episodes certainly revealed the dark side of human nature. Secretary of War J. Donald Cameron sparked a firestorm of controversy in the summer of 1877 when he had the remains of Custer and his officers recovered from the battlefield so they might be “properly prepared for burial.” Word of the selective reinterment disturbed Samuel E. Staples, whose son, Corporal Samuel Frederick Staples, died with Company I at the Little Bighorn. The grieving father offered a scathing assessment of the decision in a letter to his congressional representative:

I think the government can do no less than to give these remains decent burial, by putting them in coffins, and remove them to some suitable place.…It is hard for me to understand how the remains of the officers could be in condition for removal…while those of privates and noncommissioned officers had become food for wolves.

Public outcry resulted in the proper reinterment in place of the 7th Cavalry rank and file in 1879, followed two years later by the erection on Last Stand Hill of a granite obelisk inscribed with the names of 261 dead, including officers, enlisted soldiers, Indian scouts and attached civilians. Then, in December 1886, by executive order, President Grover Cleveland set aside 1 square mile of the surrounding Crow Indian Reservation to create the National Cemetery of Custer’s Battlefield Reservation, later redesignated Custer Battlefield National Monument. But restoring peace to this hallowed ground proved elusive. In 1988 American Indian Movement protesters accompanied activist Russell Means to the monument on Last Stand Hill, where they left a steel plaque inscribed “in honor of our Indian Patriots who fought and defeated the U.S. calvary [sic] in order to save our women and children from mass murder.” Though more than a century had passed, the Custer name clearly evoked strong feelings among Indians who felt disenfranchised from the American experience. The irony is the colonel’s remains had long been removed from the site. Exhumed at the request of his wife, Elizabeth, Custer had been reinterred with full military honors at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point on Oct. 10, 1877. Libbie’s motives were clearly driven by her husband’s legacy.

Relic hunters and grave robbers have committed the most egregious acts of desecration. In Deadwood, S.D., officials learned the full scope what it means to have a Wild West legend buried in one’s town. An early newspaper account noted how visitors, “before returning east,” would stop at the local cemetery to gawk at the hand-painted headboard of murdered gunfighter Hickok. In 1879 friend Charlie Utter paid to have Wild Bill’s original headboard and remains moved to the new Mount Moriah Cemetery, discovering to his shock that Hickok’s body had “petrified” in the calcium carbonate soil. Word of the macabre discovery spread rapidly, and bit by bit relic hunters whittled Hickok’s headboard down to nothing. In 1891 Deadwood officials commissioned a sculptor to carve a 9-foot-tall stone monument capped by a bust of Hickok with two crossed pistols below his name. Chip by chip Wild Bill aficionados also managed to destroy that monument and its 1902 sandstone replacement. Finally, in 2002, on the anniversary of his death, officials unveiled a bronze replica of the 1891 monument, which remains standing.

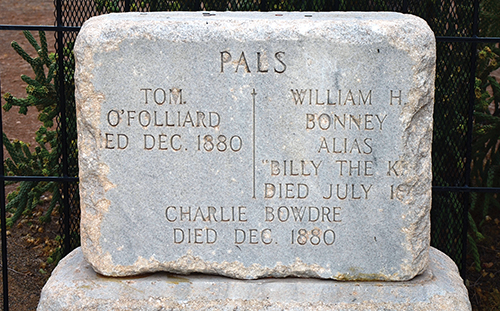

Billy the Kid’s grave attracted a bolder type of vandal. On July 14, 1881, Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett shot down the Kid at Fort Sumner, N.M., where he was buried at the post cemetery. Over time the wooden marker disintegrated. In 1940 a Colorado stonecutter and big fan of the outlaw donated a granite headstone for the Kid’s unmarked grave. Ten years later the Albuquerque Journal reported “some varmint” had “swiped the marker.” In 1975 it resurfaced in Texas. Though restored and placed within a chain-link fence, it was swiped again in 1981. Ten days later California detectives caught the thief—an opportunistic, crowbar-wielding truck driver—red-handed. Today wrought-iron fencing protects the marker.

In Sitting Bull’s case it is uncertain whether any of his remains actually remain in his original gravesite. Shot dead in a botched arrest by Indian police at South Dakota’s Standing Rock Indian Reservation on Dec. 15, 1890, the Lakota leader was taken to nearby Fort Yates, N.D., for burial. In 1953 a group claiming to represent his descendants crept into the post cemetery at night and exhumed his remains. Though they reburied Sitting Bull beneath a proper monument on a scenic Missouri River overlook in Mobridge, S.D., historians question whether they succeeded in retrieving all his bones. He was buried here, but his grave has been vandalized many times, states a plaque at his original gravesite at Fort Yates.

In the decades after Geronimo’s 1909 death rumors of grave robbers and whispers of reburials by loyal tribesmen swirled around his unmarked plot in the Beef Creek Apache Cemetery at Fort Sill, Okla. Some accounts claimed followers secreted away his body to his stamping grounds in Arizona or New Mexico. For 15 years Master Sgt. Morris J. “Mike” Swett, the post librarian, doggedly pursued the truth, and in 1930 he solved the mystery, thanks to Nah-thle-tla, a then 103-year-old cousin of Geronimo. That spring, sensing her own imminent death, she led Swett to the exact location of her famous relative’s unmarked grave. It was later marked with a pyramid of stones capped by a stone eagle.

In recent decades a story surfaced to reignite debate. In 1986 an anonymous tip alleged members of Yale University’s Skull and Bones secret fraternity had stolen Geronimo’s skull from “a tomb” in 1918. Of course, Geronimo’s grave wasn’t marked in 1918, nor were his remains ever placed in a tomb. If “Bonesmen” had indeed stolen a skull from Fort Sill that year, it likely belonged to some other poor soul. Regardless, the myth endures and was even the basis for a federal lawsuit by Geronimo’s great-grandson, Harlyn Geronimo, who sought to rebury his famed ancestor’s remains near his purported New Mexico birthplace. The lawsuit—filed in 2009 on the centennial of Geronimo’s death—was dismissed a year later. Was Harlyn Geronimo trying to preserve Geronimo’s legacy or create his own?

Quanah Parker, the last Comanche chief, is also buried at Fort Sill. The day after his death on Feb. 23, 1911, he was laid to rest in full battle regalia with a buckskin bag containing his favorite warbonnet, feathers and other keepsakes, including a signature star-shaped diamond brooch presented to him by local cattlemen. Tribesmen stood guard over his grave for four straight nights. Alas, four years later thieves dug up and looted his casket.

Just plain notoriety appears to have been at the core of at least one notable grave mystery. In the early 20th century several men surfaced claiming to be “the real” Billy the Kid or Jesse James. In 1970 a Missouri jury awarded a James descendant $10,000 for finally proving Texan J. Frank Dalton was not the famed outlaw assassinated at home by gang member Bob Ford on April 3, 1882. Questions remained. Finally, in 1995 forensics expert James E. Starrs exhumed Jesse’s remains from Mount Olivet Cemetery in Kearney, Mo., and conducted mitochondrial DNA tests to solve the mystery once and for all. “There is no scientific basis whatsoever for doubting that the exhumed remains are those of Jesse James,” Starrs concluded.

Case closed—or is it?

Grave robbers, activists, politicians, tourists, lawyers and even descendants have all cast a shadow in one sense or another over the graves of iconic Westerners. Some simply wanted to possess a “true relic” of a Wild West legend. Others had more complicated motives. Perhaps their collective obsession stems from an insatiable fascination with a time and place only discoverable at the intersection myth and reality—an elusive, untamed American West that evokes a romantic yearning for adventure. Author Louis Fairchild once quoted a mournful 19th-century ballad to address this romantic theory:

They have gone the long dim trail,

Down the shadow of the vale,

O’er their long graves the lean

Coyotes sigh.

“Easterners had thoughts of a lonely but peaceful grave with sounds of coyotes yelping in the distance,” Fairchild wrote. “The wrangler saw these coyotes fighting over his remains.” Men such as Custer, Geronimo and Hickok earned a sort of immortality through their daring deeds, thus sparking an attraction to their final resting places. That connection—whether real or perceived—has attracted the masses, dictated political agendas, tempted thieves and garnered notoriety for generations. In his 1982 book Inventing Billy the Kid author Stephen Tatum offered perhaps the most reasonable advice on how best to retrace the Kid’s path in New Mexico. “Not the least of ways to travel through Kid country,” he wrote, “is the route of the imagination, a route that has known few boundaries in the century since the Kid’s death in 1881.” Thus will the final resting place of any legendary Westerner be forever in the mind.