The Cone family exemplified Jewish immigration in the South by encouraging industrial and cultural progress

“You may shed tears, because you are leaving your parents’ house, your Father, Brothers and Sisters, relatives, friends and your native land, but dry your tears, because you may have the sweet hope of finding a second home abroad and a new country where you will not be deprived of all political and civil rights and where the Jew is not excluded from the society of all other men and subject to the severest restriction, but you will find a real home land where you as a human being may claim all human rights and human dignity.” —Joseph Rosengart of Buttenbaum, Bavaria, to nephew Herman Kahn, 17, about to emigrate to the United States in 1845.

After an Atlantic crossing and a stay with an older sister in Richmond, Virginia, young Kahn renamed himself Cone and started peddling. By 1853, Herman Cone had married Helen Guggenheimer, also of Bavarian Jewish descent, and with her kin opened a dry goods store in Richmond, Virginia. The couple moved to Jonesborough, Tennessee, which, besides being a commercial hub of East Tennessee and an abolitionist and Quaker stronghold, was home to other German speakers. The Cones had 13 children and an outsize economic and cultural impact. Under Herman’s tutelage, eldest sons Moses and Ceasar grew up to helm a textile company that transformed the Southern cotton industry. Daughters Claribel and Etta acquired a world class array of modern art. The Cone Collection now is housed at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The Cone saga threads through American history. Among the first Jewish emigrants to settle—and thrive—in Jonesborough, the family, unlike most East Tennesseans, stood with the Confederacy. During the Civil War, the Cones closed their store and bought farms and three enslaved workers to cultivate their acreage. After the war, Herman Cone pledged loyalty to the United States. To reestablish his retail business, he added a Unionist partner.

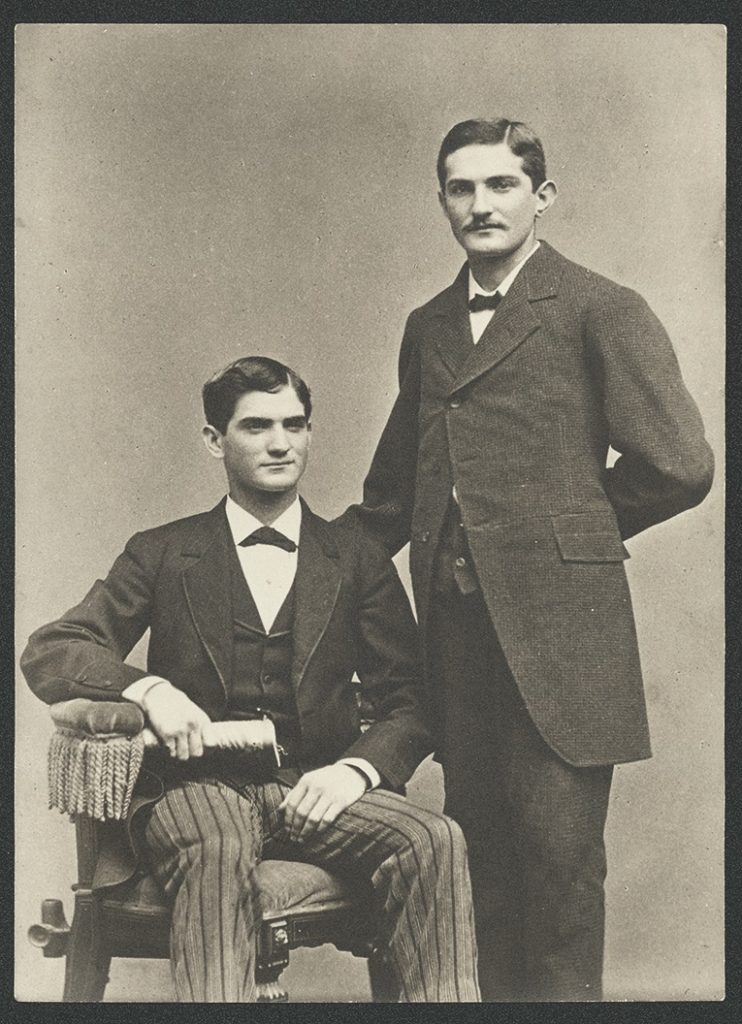

By 1870 Herman had moved his family to Baltimore, also a German-Jewish émigré bastion. The Cones enrolled their offspring in public school. The sons learned their father’s business. Moses, “five feet ten, square and spare, handsome, with arresting brown eyes,” according to a family account, was especially adept. Confident and outgoing, he excelled at connecting with prospects while traveling with his father around Virginia and North Carolina seeking customers for trade goods and tobacco. Herman Cone expected Moses to take over their Virginia accounts. Moses, who described himself as having “goaheaditiveness,” balked at the notion.

“The slow pay and no pay customers are in bunches,” he said, singling out eastern Virginia. “The soil is worn out or tobacco [which depletes the soil], climate’s too cold for cotton, trees too lumbered out,” he told his parent. “I’m sorry, Father. I would concentrate our merchandise in the Piedmont Carolinas where the people have several crops and some manufacturing started.”

In 1884, Herman Cone turned his business over to Moses and Ceasar. Trading with mills, where owners of company stores short on cash often relied on barter, the brothers ended up owning stocks of cotton. Investing in textile mills around Asheville, North Carolina, the Cones also contracted with millers willing to guarantee a standardized product. By the 1890s, some 47 of North Carolina’s and Georgia’s 50 mills had joined the Cone Export and Commission Company, nicknamed “the Plaid Trust” after the favored weave, and were paying the brothers a 5 percent commission on sales. In 1895, the two opened Proximity Mill near a train line in Greensboro, North Carolina. Moses chose Greensboro not only for its six rail lines and access to cotton but its legacy as a Quaker town kinder to Jews than rival Winston-Salem. In 1900, the brothers partnered with others to open Revolution Mill, the South’s first cotton flannel mill, also in Greensboro. In 1905, the Cones opened 1,000-loom White Oak mill, churning out sturdy denim fabric. The Cones were generous employers and neighbors, endowing housing, schools, gardens, and medical care. In 1899, Moses Cone led the list of donors underwriting what became Appalachian State University. But the Cones also opposed unionization. After crushing a strike in 1900, the brothers began requiring their employees to sign company loyalty oaths.

In 1901, Moses married German-born Baltimorean Bertha Lindauer. The couple built a sprawling estate at Blowing Rock, North Carolina, near Asheville. An avid conservationist, Moses planted 10,000 trees of 25 varieties. He was 51 when, a year after completing a round-the-world-trip with his wife and sisters Claribel and Etta, he died in 1908 of pulmonary edema. Moses having left no will, by state law his wealth was split among his wife and siblings. Claribel and Etta, living on stipends from the family business, routinely visited Europe. In Paris they communed with their longtime friend, the bohemian Baltimorean Gertrude Stein. Through Stein, Claribel and Etta befriended young artists Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Coincidentally, Matisse had grown up in a fabric-business family, a likely factor in his love for color, pattern, and texture. Etta, more retiring than Claribel and a self-taught student of art, was particularly devoted to that field. She and Claribel acquired hundreds of paintings by Matisse and other artists, including Picasso, Paul Cezanne, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Ceasar Cone ruled the family company with an iron but innovative hand. In 1913, he interjected Greensboro into a historically Northern niche by opening Proximity Printworks to handle the complex step of printing on fabric with dyes. Ceasar also closely allied with San Francisco-based Levi Strauss Company, maker of denim clothing popular with rail, mining, and ranch workers out West. By 1922, the Cones’ White Oak Mill, enjoying an exclusive deal to make denim for Levi Strauss, was dominating production of that fabric.

The Proximity mill closed, but the remaining Cone textile businesses survived Moses and Ceasar by decades. The company continued to pioneer, including treating wastewater from its mills starting in the 1940s, long before anti-pollution regulations arrived. During World War II, Cone factories shifted to war-related garments, in peacetime pivoting again and again, as when, in 1962, Cone introduced a form of stretch denim. In the 1980s, however, the company encountered crosswinds as American manufacturing began shifting overseas.

In 1994 the North American Free Trade Agreement lowered barriers to goods made abroad. In 2004, Wilbur Ross—today U.S. secretary of commerce—bought Cone Mills Corporation and renamed it International Textile Group. For a time, the White Oak mill produced artisanal denim. In 2016, Ross sold ITG. In 2017, White Oak, the last remaining Cone plant, closed. But the family’s legacy continues. In 2012, Revolution Mill, on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984, was repurposed into apartments and workspace for artists and businesses. Proximity Printworks was named a National Historic Place in 2014. White Oak Mill was demolished in January 2019, but its fabric business lives on as Cone Denim, a unit of Elevate Textiles, owned by investor Tom Geres. At mills in Mexico and China, Cone Denim has adopted production methods that reduce CO2 emissions and waste.