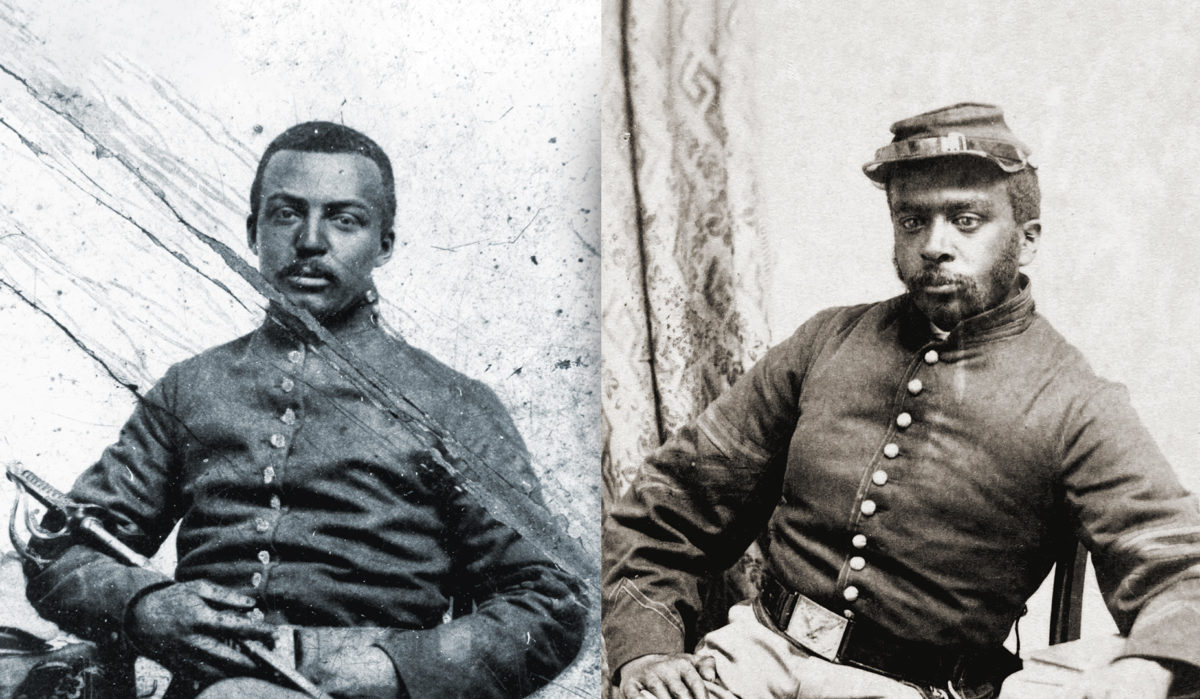

More than 20 years ago, John D. Warner Jr., a graduate student at the time, came across an arresting account by Union officer Charles Francis Adams Jr., of leading Black troops into Richmond after it fell on April 3, 1865. He wondered why he had not heard that story before. Now Warner, archivist for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, has written Riders in the Storm: The Triumphs and Tragedies of a Black Cavalry Regiment in the Civil War, which describes the experiences of the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry—the unit Adams commanded in the occupation of Richmond. Published by Stackpole Books, Warner’s book covers the experience of Black troops in the Union Army as well as detailed coverage of the complexities of recruiting Black soldiers and white officers for service in a regiment like this.

Why was the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry formed? Was this the first Black cavalry unit?

The cavalry were considered the fighter pilots of the 19th century. They were perceived as being an elite force — the scouts, the eyes of the army. There were a couple of USCT Cavalry regiments and a couple of regiments raised in the western area of the campaign. So where we are at the end of 1863 is that African American troops had been raised and were being raised following promulgation of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. The 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments had been in the field since June 1863, and by the end of 1863 there is a recruiting frenzy, with African American troopers part of the state quota. The bounty of $350 was equivalent to a year’s salary in many cases: what today would be in the $30,000–$50,000 range.

Yet the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry went into battle without horses. And not only were they dismounted, they also didn’t start out getting full pay.

When the 5th Massachusetts arrived in Washington, the men didn’t know they would be dismounted; certainly in their minds, the bargain they had made in joining had not been kept. Two or three other regiments that happened to be white were also dismounted because of the shortage of horses. The Civil War is in many ways the bureaucratization, the organization of war. So, “We’re not going to be able to get you horses” is in some ways understandable when you look at the big picture. As for pay, they had been promised the same as Federal troops, but the War Department told the men, “We will pay you as laborers,” not what white troops were being paid. That was specific to all African American troops until the law changed on June 15, 1864. It was scandalous it took 18 months to do so.

What happened when they were in service?

The unit had been trained according to Cook’s Cavalry tactics, and when Massachusetts Governor John Andrew and his cadre decided to recruit officers for the regiments, they wanted people who had experience and who were committed to the movement, so to speak. If you had cavalry experience, you could be promoted from an enlisted non-commissioned officer to lieutenant or even a captain, which is a pretty big jump. So having that experience as cavalry troopers in White regiments, you show up in Washington, the theater of operations; you’re now dismounted and you’re now infantry. So it’s: “What do we do? We don’t have any training in moving infantry troops around, facing movements, how to shake out a line of battle, how to get to your squads, your platoons, companies organized in such as way as to be effective in bringing fire upon the enemy.” As far as what the 5th went through, they did go into battle, they did have casualties. They felt they came through it all right, acted as they should, nobody ran away. But the fact is that they were removed from the 18th Division and sent to Point Lookout [Md.] to guard Confederate POWs. They were in effect exchanged for a trained USCT infantry regiment to become prison guards.

That must have been demoralizing.

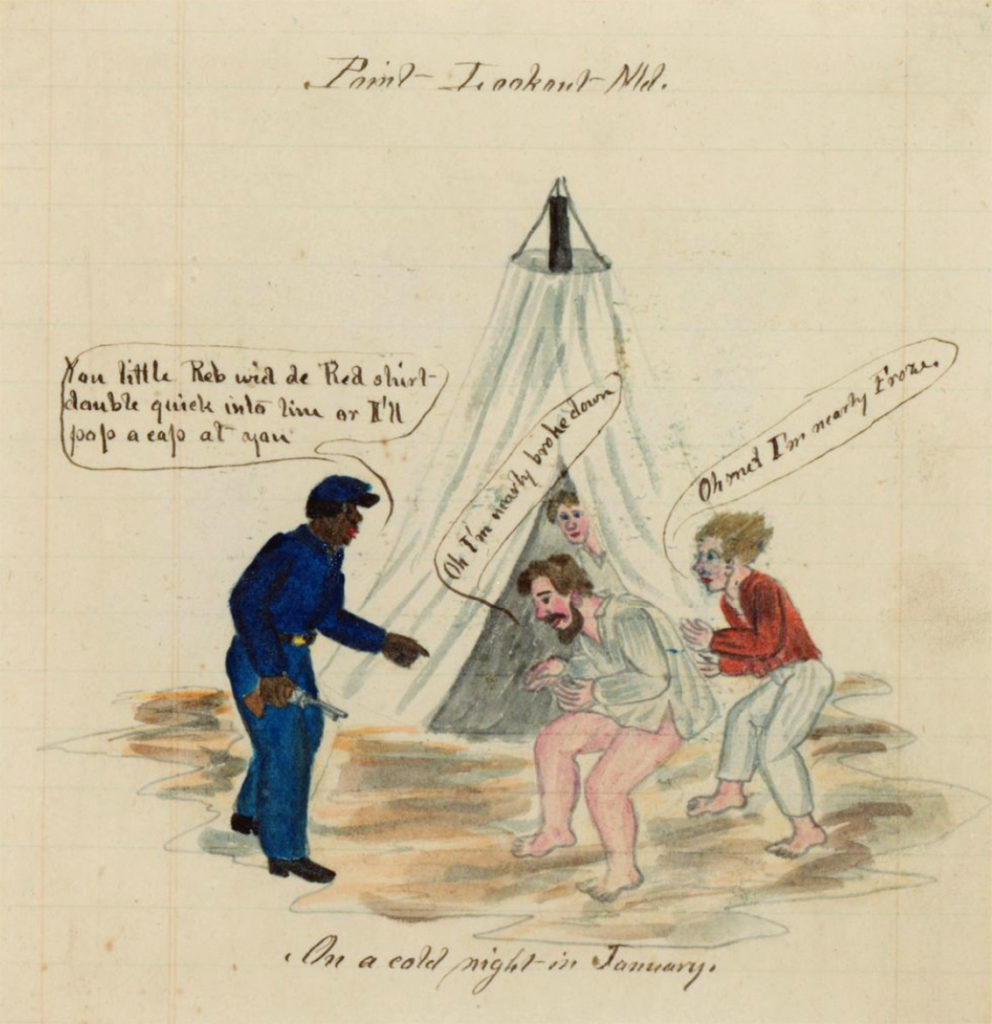

Yes, but in many ways it was fascinating. We have POW accounts, from Sidney Lanier, and John Omenhausser’s watercolor drawings to show what went on. This regiment knew the stakes, that it was an existential fight. You’re a young man and you join the Army at the zenith, when it is a fight to the finish, so to speak. When you look at the regimental records from when they formed in Massachusetts, about 800 of the 1,000 men who went off to war were signature illiterate. They made a mark, not being able to write their names. So there isn’t this vast body of letters or a cache of first-person accounts available. But you see in the POW accounts and particularly the watercolor drawings that these were men of agency. They were doing what they had to do. Serving their country, knowing that they are also acting to free their race. In one Omenhausser drawing, he has the Black prison guard on the outside of the palisade looking down. “Do you belong in there” he has the trooper say, getting “I didn’t see the line” as a reply. “You better take care of it, or I’ll put a round in you,” the trooper responds. “The bottom rail is on top.” People says it’s anecdotal, but it’s noteworthy because it was what was being said by some people.

How does the unit get involved in the fall of Richmond?

It’s a wonderful story, in some ways apocalyptic. The Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865, leads to breaking the Confederate lines. A messenger comes into a church in Richmond where Jefferson Davis is sitting with his family and whispers, “They’ve breached the line, it is time to pack up and get out of town.” Colonel Adams had petitioned for his regiment to be put back in the field, so they pack up and take their horses and all their gear and turn in their rifles for carbines, sabers, and pistols. Back to being cavalry, they move up into Virginia. As the city is abandoned, the Confederates, in an attempt to deny war materiel to the approaching Union army, or perhaps out of pure cussedness, decide to blow up the Tredegar Iron Works and the bales of cotton that are being stored in the warehouses. There’s a high wind. Before long, about 20 city blocks are burned to the ground. The 5th marches in and they are the first African American soldiers into the city. In some ways, it was sort of unfortunate that they weren’t able to be in action as cavalry because we would have learned of their true mettle, but they entered as a duly brigaded regiment of the 25th Army Corps. Again, it’s a pretty good story.

How would you sum up the unit’s wartime experience?

Many times people ask me: How come this has never been told before? In some ways it is because the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry didn’t suffer terrible casualties. They served with fidelity, endurance, perseverance. In some ways, if you owe somebody something, it’s best to say that account has been settled, even if it may not have been. Certainly the sad and corrosive story of racism in 19th century and 20th century to the present day would say these men were ignored because of who wants to hear this story. In my opinion, it’s a great story. I would say it’s long overdue that they get the recognition that they deserved.

How did the unit wind up serving in Texas after the war ended?

The Union government sent entire an army corps down and a whole cavalry division. At one point they had upward of 50,000–60,000 troops there. The South had generally surrendered, but there were other units in the Trans-Mississippi that were still intact. It was a very unsettled time. The option that officers had to resign was not available to the troopers. As enlisted men, you’re stuck. You find that as a pattern that occurred among African American troops in the Union Army after the war. The Army wanted them to stay on and they were used for occupation and were a big force in Texas. The white troops—some had been involved since 1861—get to go homes after a nice parade. By the end of May, most troops are getting on a train going home, while the African American troops are not going anywhere. You take troops, you break them up, squads or companies are working on railroads, doing fatigue duty.

How long did you work on this book?

It started as a 500-page dissertation, dry and rather straightforward. I received my dissertation right before the internet came into being and made research possible at least to tease out sources. I had heard about the Omenhausser watercolor drawings of POWs at Point Lookout. For a long time, I tried to find them. The World Cat database is something that all research libraries are part of. You can find who holds Weekly Anglo African and whether it is original or in microfilm. I had seen an image of an Omenhausser watercolor back in the ’90s, but I couldn’t get ahold of the drawings until I went to the Special Archives of the University of Maryland and that was in the 21st century.

Riders in the Storm

The Triumphs and Tragedies of a Black Cavalry Regiment in the Civil War

By John D. Warner Jr., Stackpole Books, 2022

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.