Boston-area poet offers a compelling look at what tore our nation apart

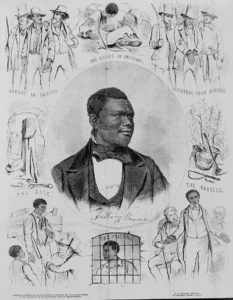

By day, Kevin Gallagher is professor of global development policy at Boston University. In his off-hours, he writes poems, and his latest work, Loom, explores the run-up to the Civil War through the stories of various historical characters, including cotton tycoon Amos Adams Lawrence, escaped slave Anthony Burns, and millworker Lucy Larcom. In 48 poems, Loom brings to life Americans swept up in an economy dependent on making textiles and enslaving cotton workers.

What inspired Loom?

I wrote the first draft while I was in Alexandria, Va., and a visiting professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. We’re from Massachusetts, and my son had been in a local public school there, and he heard versions of what the war was about that were different from what he heard back home. That sparked a wonderful conversation and a re-exploration for me. We were going to Civil War battle sites all the time on the weekends, after school, going to the library and taking out all sorts of books. Then the Freddie Gray incident occurred in Baltimore, and people I was working with at Johns Hopkins were abuzz about that. I’ve always been interested in the rise of capitalism and the role of mills in Lowell, Mass., and one day when my son and I were on the Gettysburg tour, there was this half-second when we were told that one of the turning points of the war was when Lowell textile mills owners severed their alliance with Southern slaveholders and began putting their resources into the war effort. That was the perfect-storm moment when I wrote one of the first poems related to the project.

What was that?

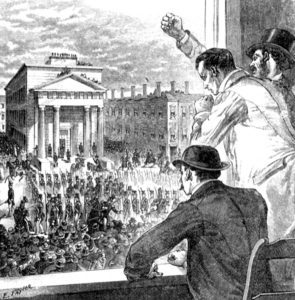

It is “The Stark Mad Abolitionist” poem about textile tycoon Amos Adams Lawrence. That is the heroic act of the whole sequence: “I put my face in my hands and I wept/Now I’m a stark mad abolitionist.” One of the richest men in America at the time acted, against his material interests, for racial equality and social justice. Of course, a lot of abolitionists and folks who engaged in the Underground Railroad were pushing for equality for moral reasons, but it is really an act of heroism to sever that economic alliance, and I hadn’t appreciated how pivotal that was. After Amos Lawrence makes the change, he basically financed people from Massachusetts to go to Kansas and vote for it to be a free state. And Lawrence, Kan., is named after Lawrence, of the same Lawrence family that lent its name to Lawrence, Mass. None of us knew that. It was also Amos Lawrence who recruited and financed John Brown, gave him Sharps rifles, and sent his group out to Kansas to protect the antislavery folks from Massachusetts from attack by Missouri ruffians who wanted the vote to go the other way. There are individual monologues in the book, but it’s a narrative arc with an epic heroic moment with the Lawrence family.

Are you drawing on a tradition in poetry?

For example, William Carlos Williams wrote a long piece about Paterson, N.J., and Seamus Heaney wrote a book called North [about the troubles in Northern Ireland]. These were folks who looked at history to talk about the present, but to let history speak for itself. I was inspired by them. In Loom, the poems are usually either in sonnets—14 line sonnets and a couple of the epiphanies are villanelles, a 19-line form of poetry.

Who is your audience?

The book came out last September and I’ve probably done about 20 readings. About five to eight have been your traditional poetry venues. I’ve given readings at libraries and historical societies. Perhaps the pinnacle was doing it in Lowell at the National Historic Park at the Boott Cotton Mill and Museum in their amphitheater and showing slides of images of artifacts from the book. You give the reading in poetry, and then you have a 45-minute conversation about the history, and then someone brings up Black Lives Matter and then you have very interesting conversations that aren’t led by me but are led to.

How did you create the voices and characters?

Poetry has gone the way of abstract painting—where it’s got its own community and you have to know the secret handshake to know what’s going on and even then it might not be that interesting—but this is public stuff. It is written in a way that folks can understand. Two to three of the lines of each poem are pretty close to what was actually said by that particular individual, just to sort of ground it in truth. I am not trying to take my politics and dump it on other people. This is really their voices, strung together to tell a particular story that did happen in life. I wanted to be really true to these people and give them the voice. I also feel like I am making poetry relevant again. A lot of folks say they haven’t been to a poetry reading ever.

From Kevin Gallagher’s 2016 book of poems Loom

Reprinted courtesy of MadHat Press

The Last Full Measure of Devotion

My sword got stuck between his ribs.

I kicked my foot into his chest.

I pulled it out with both hands.

In the same motion I swung right

Into the gut of another.

He hit the ground; I grabbed his Colt.

I shot one who was charging me

with a rifle and bayonet

soaked with blood and blue cloth.

‘Without support of any kind’

Captain said ‘retire by prolong’

so McGlivery could fill the gap.

We went quiet when he said

‘Hold position at all hazards.’

I thrust my sword even harder

Into a Mississippi thigh

as he tried to kick it from my hand

then go after our best gunner.

I used rammer heads. I used hand-spikes.

I kicked them in the groin.

I kneed them in the face.

Then I shot them in the stomach.

There was so much smoke around me

I didn’t know their numbers.

Too many Barksdale sharpshooters.

Too many from South Carolina.

Too many 21st Mississippi.

Too many rocks for our wooden wheels.

Too many dying men and horses

to move our Napoleons back.

We saw Bigelow get shot twice

but the bugler took him to the rear.

We kept on trying to fight.

I got stabbed twice in the ankle.

I felt he shell go in my side.

My eyes were open when I died.

[/box]