Could the lanky, white-haired gentleman with the hooked nose, who in his last years charged .50 cents to tour the James family home, really have been a cold-blooded killer? You bet

Editor’s note: Mark Lee Gardner’s "The Other James Brother," published in the August 2013 Wild West, won the 2014 Spur Award for best Western short nonfiction from the Western Writers of America. WWA also awarded Gardner its 2014 Spur Award for best Western historical nonfiction for his book Shot All to Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid and the Wild West’s Greatest Escape.

Frank James heard Cole Younger yell at him, again, to come out of the bank. Bob Younger and Charlie Pitts (real name Samuel Wells) had already jumped the counter and bolted out the door into the street, where two of the James-Younger Gang lay dead, shot down by the plucky citizens of Northfield, Minnesota. As Frank jumped up on the counter, he turned and glared at the man who had prevented him from getting at the money in the bank’s safe—acting cashier Joseph Lee Heywood.

Heywood, bloodied and dizzy from a blow Frank had given him with the butt of a pistol, staggered toward his desk. Seething with anger, Frank raised his revolver and fired at Heywood. Despite the proximity, his shot missed. Heywood fell into his chair, or perhaps he was dodging behind his desk. It didn’t matter. Frank cocked his revolver and, “with the expression of a very devil in his face,” recalled the only eyewitness, “put his pistol almost at Heywood’s head and fired the fatal shot.”

In the nearly 137 years since the infamous September 7, 1876, Northfield bank raid, most writers have identified not Frank but brother Jesse James as Heywood’s murderer. Only a few days after the raid Detective Larry Hazen, who had been on the trail of the James-Younger Gang since their Missouri Pacific train robbery near Otterville, Mo., two months earlier, told a St. Paul reporter, “Jesse James is always ready for murder, and he is undoubtedly the one who fired the fatal shot at Heywood.”

It made sense. Jesse could be hotheaded and vengeful, a deadly combination, and as the supposed leader of the gang, he must have been in the bank. But in a sworn affidavit previously unknown to scholars, Frank Wilcox, the bank’s assistant bookkeeper and the only eyewitness to the shooting, named Frank James as the murderer—and this after visiting Frank in temporary custody at the Jackson County Jail in Independence, Mo., in November 1882.

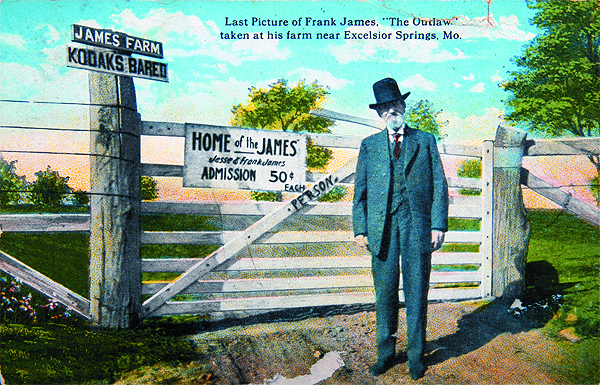

Yet most people today think of Frank—if they think of him at all—as the “better” of the two James boys, for several reasons. After being acquitted of murder and robbery in highly publicized criminal trials in 1883, Frank lived for more than 30 years as a peaceable citizen. He demonstrated time and again that he was a hardworking family man. Many of those who met the former bandit thought he resembled a preacher or, according to one journalist, “the president of a rural bank.” Could the lanky, white-haired gentleman with the hooked nose, who in his last years charged .50 cents to tour the James family home, really have been a cold-blooded killer? You bet.

Nearly everyone knows how a teenage Jesse Woodson James cut his teeth in the killing business riding alongside Missouri Bushwhacker William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson and other Rebel guerrilla leaders in the Civil War. It’s a seminal chapter in the Jesse James saga. But we tend to forget that brother Alexander Franklin James had identical experiences, and that he got a good head start in the savagery that marked the fighting along the Kansas-Missouri border. When guerrilla chieftain William Clarke Quantrill swooped down on Lawrence, Kan., in August 1863, Frank James rode with him. Quantrill’s men gunned down close to 200 men and boys, mostly civilians. Jesse was at home tending crops and would not join the Bushwhackers until nearly a year later.

Frank generally shied away from talking about Lawrence, but he would discuss Quantrill and the violence of the Bushwhackers. “We knew he was not a very fine character,” Frank told a reporter, referring to the guerrilla leader, “but we were like the followers of [Pancho] Villa or [Victoriano] Huerta: We wanted to destroy the folks that wanted to destroy us, and we would follow any man who would show us how to do it. Besides, I was young then. When a man is young, his blood is hot; there’s a million things he’ll do then that he won’t do when he’s older.”

Frank would not discuss his and Jesse’s long career as outlaws, at least not publicly. To do so would have put him at risk of being arrested for any number of crimes. “I neither affirm nor deny,” was his typical non-answer to journalists who probed him about various robberies. But there were plenty of others, including former gang members, who had lots to say about the James boys.

Frank and Jesse were strikingly different, in both looks and personality, so much so that an ugly rumor spread that the men were the offspring of different fathers. Frank was four years older and, at approximately 6 feet, slightly taller than Jesse. Frank was also slim, almost effeminate looking, with a small neck and a long, narrow face flanked by large ears. “Spare but sinewy” was how one reporter described him.

Jesse was more sturdily built and heavier than Frank. He had an oval face and a slightly turned-up, or pug, nose. The more handsome of the two, Jesse had clear blue eyes that seemed to move constantly—almost nervously.

One of the more interesting descriptions of Frank and Jesse in their prime comes from John Newman Edwards, the booze-loving newspaperman and former Confederate soldier who was the James boys’ chief defender—and the main architect of their legend. He interviewed the outlaws in 1873; Frank was 30, Jesse 26.

Jesse laughs at everything—Frank at nothing at all. Jesse is lighthearted, reckless, devil-may-care—Frank sober, sedate, a dangerous man always in ambush in the midst of society. Jesse knows there is a price upon his head and discusses the whys and wherefores of it—Frank knows it, too, but it chafes him sorely and arouses all the tiger that is in his heart. Neither will be taken alive.

Jesse James’ brother-in-law, Thomas Mimms, echoed Edwards’ observations. “Frank was quieter and more reserved than Jesse,” Mimms told a reporter. “Jesse was of a roving disposition, restless and daring. He liked some reckless expedition.…He was more reckless in going among strangers than Frank. Jesse would often put up at a house where he knew nothing of the character of the people. Frank would never stop anywhere but at the house of a friend in whom he had confidence. Frank never gave any clues as to his whereabouts.”

An uncle of the James boys said Frank’s personality was very much like that of his father, the cultured, college-educated Baptist minister Robert James, who died in a California gold camp from an unknown illness in 1850. Jesse’s nature more closely resembled that of his strong-willed Southern partisan mother, Zerelda James Samuel.

While the ever-cautious Frank was loath to draw attention to himself, Jesse loved the notoriety generated by their daring robberies and escapades. In casual conversations with strangers Jesse seldom failed to bring up the James-Younger Gang so he could hear what they had to say about the outlaw band. And he frequently wrote letters to various newspapers, always denying the involvement of the James brothers in one bold holdup or another and railing against those who hunted them, claiming he and Frank were being unjustly persecuted when all they wanted was to live normal lives.

It is Jesse’s strident letters to the press that have generally led to the belief he was the true leader of the gang. And there is evidence that Jesse was more often the leader than not. Descriptions of the bandits involved in the July 7, 1876, Rocky Cut train robbery leave no doubt as to the identity of the leader with the small hands (he wore a No. 7 glove) and striking blue eyes that seemed to blink more than normal (Pete Conklin, the train’s baggage master, concluded that Jesse conducted the robbery in the train cars while Frank directed the men outside).

It’s also clear Jesse was the one behind the subsequent trip to Minnesota. Once there, he learned that carpetbagger and former Union Brig. Gen. Adelbert Ames was connected to Northfield’s First National Bank, so he pushed for that bank as the gang’s target. In the wake of the botched holdup, which left gang members Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell dead in the street, eyewitness descriptions of the gang’s flight through Minnesota’s Big Woods also point to Jesse as the one giving orders.

But while Jesse promoted himself as the leader and does seem to have given orders in the field, Frank may have had a more significant role than generally believed. John Samuel, Jesse and Frank’s half brother, said Frank and Cole Younger were the acknowledged “brains” of the outfit. “It was claimed,” Samuel said, “that Frank planned and Jesse executed. Frank was certainly the cool man of the two, and Jesse was a little bit excitable.”

Former gang member George Shepherd told a reporter that Frank “is the most shrewd, cunning and capable; in fact, Jesse can’t compare with him.…It’s Frank that makes all the plans and perfects the methods of escape. Jesse is a fighter, and that’s all.”

But while Frank might have been the brains, he was not as popular with gang members and associates as Jesse. Charley Ford said that although both Frank and Jesse wanted to be leaders, the men preferred Jesse because he was “bolder.” And they enjoyed Jesse’s keen sense of humor, as well as his boisterous talk—even if it was usually about himself. Frank always seemed to be arguing about something with Jesse and the rest of the gang, and he “cared nothing for his men.” After a raid, Ford recalled, Frank “would pocket all the money he could and let his men shift for themselves,” while Jesse “looked after his men and was always willing to share his spoils with them.”

“Frank James put on too much, anyhow,” said Jim Cummins, another associate of the James boys, although whether or not he participated in any of their robberies is debatable. “He used to spout Shakespeare when we were all a-hidin’ out, and that didn’t go down with me. What’d Shakespeare have to do with sidesteppin’ a bunch o’ Pinkertons or a posse o’ deputies, I want to know?”

Frank indeed was a fan of Shakespeare and was also known to quote the Bible. In addition to reading, his other great pleasure was tobacco; it was rare when he didn’t have a chew in his mouth. In his later years the former outlaw reportedly never touched liquor, but that’s not what Charley Ford remembered. “Frank would get dead drunk,” he said. Not Jesse, though, who never touched liquor when on a raid.

Although Frank may not have been as popular with the gang, no one questioned his nerve—or his willingness to kill. “Frank was a bad man in a fight and…a great deal more cunning than Jesse,” claimed Bob and Charley Ford. After the Ford brothers assassinated Jesse in St. Joseph, Mo., on April 3, 1882, they received several threatening letters signed “Frank James.” A reporter asked the Ford brothers if these letters worried them. With grim seriousness in his voice, Charley replied, “Frank James is not in the habit of sending notices; he generally carries them himself.”

John Nicholson, a grandson of Jesse and Frank’s half sister, never forgot a chilling comment his grandfather made about the outlaw brothers: “I heard my granddad say that Frank was the cold-bloodedest one of the two. If he said he was going to kill ya, he would kill you, but you could talk Jesse out of it.”

Was Frank James a psychopath? No, and neither was Jesse for that matter, surprising as it may seem. One only has to look to their loved ones, particularly their wives and children, to see that Frank and Jesse do not fit the definition of antisocial or unhinged. Annie Ralston James eloped with Frank in 1874 and remained married to him until his death more than 40 years later. “No better husband ever lived,” she told reporters after Frank died. And little Jesse Edward James, who was 6 when his father was killed, recalled the infamous outlaw as being “very kind to mother and to sister and to me. I remember best his good-humored pranks, his fun-making and his playing with me.”

Yet at the same time Frank and Jesse were also violent killers. A key to unraveling this contradiction is found in something newspaperman Edwards observed in 1873. The outlaw brothers, he said, were “creatures of the war.” The James boys’ defenders have often cited the bitter effects of the Civil War to excuse their outlawry, but their Bushwhacker experiences certainly numbed them to violence, to the taking of human life. Consequently, whoever stood in Frank and Jesse’s way, or worked against them, or harmed them or a family member was the enemy. And whether that enemy was a bluecoat, a Pinkerton or a stubborn bank cashier, the James boys never hesitated to pull the trigger.

As the brothers fled through Iowa following the Northfield debacle, Frank used his murder of acting cashier Heywood as a teaching moment. He suggested to a Sioux City physician they encountered (and temporarily held captive) that he “tell the bankers of Sioux City when we come there not to do as Heywood did but to give up the keys, and there will be no trouble.”

Five months after Jesse’s death Frank, with the considerable help of Edwards, turned himself in to Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden in a carefully crafted PR tour de force. Before an audience of dignitaries in Crittenden’s private office, Frank unholstered a Model 1875 Remington revolver and presented it to the governor. “I make you a present of this revolver,” Frank said before the stunned crowd, “and you are the first, except myself, who has laid hold of it since 1864.” The scene came off very much like a defeated general presenting his sword to the victor.

When Charley Ford learned of Frank’s speech about the pistol, he was incredulous. “Why, I put Frank’s pistols on and he put mine on, to see how they would fit, when I was at his mother’s, in June 1881.” Of course, the more obvious problem was that the Model 1875 did not exist in 1864. It made for an undeniably breathtaking moment, though.

Frank’s subsequent stay in the Jackson County Jail, awaiting arraignment on various charges for murder and robbery, proved another PR coup. Crowds flocked to see the outlaw. They were already inclined to be sympathetic toward Frank because of how Jesse had been killed—the way Crittenden had colluded with Bob and Charley Ford to eliminate the bandit leader seemed underhanded and cowardly. But when they saw Frank with his wife and son and how he lovingly held his boy and laughed and played with the youngster, they could not help but like the man. Frank even made it a point to politely shake hands with each visitor, telling them he was glad to meet them.

“Your stay in jail has been worth millions to you as far as public opinion is concerned,” an ecstatic Edwards wrote Frank. “In fact, it was the best thing that could have happened. You can have no idea…how rapidly public sentiment is gravitating in your favor. You have borne yourself admirably, and every man who has seen you has become your friend. Do not refuse to see anybody, and talk pleasantly to all.”

Frank faced trial for only two offenses: the murder of a passenger on a train the gang robbed near Winston, Mo., in 1881, in which Frank may very well have fired the fatal shot; and the robbery of a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers paymaster in northern Alabama, also in 1881, and of which Frank was actually innocent. Each trial ended in acquittal. By March 1885 prosecutors had dropped all other cases, including an indictment for the Rocky Cut robbery.

Opportunities were limited for a former outlaw of Frank’s notoriety, but to his credit he turned down most—though not all—offers to appear onstage over the next three decades. For more than five months in 1903 he and Cole Younger, who spent nearly 25 years in the Minnesota State Prison for his role in the Northfield bank raid, toured in The Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West Show. Mostly, though, Frank worked variously as a shoe store clerk, a starter at racetracks, a doorman for a St. Louis theater and a farmer, happy to let the big shadow of Jesse deflect attention away from him.

In his last years Frank became what was surely the best tour guide the old James farm near Kearney, Mo., ever saw—certainly the most authentic. “In his manner there is a strong note of the showman,” wrote one visitor to the farm. “It is not at all objectionable, but it is there, in the same way that it is there in Buffalo Bill [Cody].…He is clearly an intelligent man, but he has been looked at and listened to for so many years as a kind of curiosity that he has the air of going through his tricks for one—of getting off a line of practiced patter.”

That patter never fooled old Jim Cummins, though. He said that Frank had pulled the wool over people’s eyes. “Frank posed for years as the best of the two [brothers],” Cummins said from a chair at the Confederate Home in Higginsville, Mo., in 1915, months after Frank’s death. “He let the whole world say and believe that Jesse was the worst of the two. He never opened his mouth to correct it. I knew them, and I tell you that both of them were bad enough, but Jesse was the better of the two.”

Author Mark Lee Gardner profiled Pat Garrett in the August 2011 Wild West and the book To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett. He recently released the CD Outlaws: Songs of Robbers, Rustlers and Rogues.