The court expanded the Gibbons standard to include labor relations and other activities with even an indirect effect on interstate commerce.

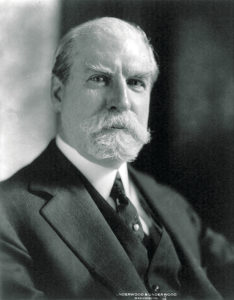

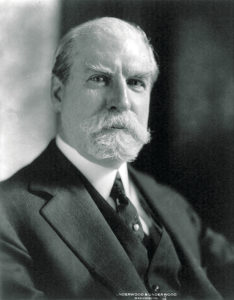

On April 12, 1937, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a keystone decision paving the way for near open-ended federal regulation of business. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes authored the ruling in a jurisprudential U-turn that for the rest of his life Hughes denied making. The decision upheld the constitutionality of provisions in the 1935 National Labor Relations Act easing the path for workers to organize. The now-reinforced ruling ordered company managers to bargain with unions picked by workers to represent them and outlawed punitive actions against pro-union employees. The decision set up an independent agency, the National Labor Relations Board, to enforce the provisions of the NLRA, widely known at the time as the Wagner Act—its principal sponsor had been Senator Robert F. Wagner (D-New York).

The Wagner Act was a major component of the New Deal crafted by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration to extricate the United States from the Depression by deepening federal involvement in what until then had been seen as commercial activity beyond Washington’s purview. Roosevelt’s scheme foundered on deep hostility to such expansionism on the part of a majority of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1935, justices threw out the entire National Industrial Recovery Act under which the Roosevelt government had tried to set standards for businesses, calling the law unconstitutional because the company in the case—a New York City poultry dealer who bought chickens from New Jersey—had no direct impact on interstate commerce, putting its operations beyond congressional jurisdiction. In 1936 the court declared unconstitutional wage and hour standards set in the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act, finding coal mining to be a strictly local affair. In both cases, Hughes voted to scuttle the statutes. “The power to regulate interstate commerce embraces the power to protect that commerce from injury,” Hughes wrote in the coal case. However, he substantially limited that holding by writing that lawmakers cannot use the power “to regulate activities and relations within the states which affect interstate commerce only indirectly.”

Given Hughes’s and the court’s track records, many businesses expected them to scuttle the Wagner Act as well; they ignored the NLRB and dealt harshly with union activists. The NLRB ordered companies to end such practices. Industry’s refusal to do so set up court tests of the Wagner Act’s enforceability. Relying on the high court’s decisions in the Recovery Act and bituminous coal cases, appellate courts sided with business, calling labor relations at any single plant local in nature and therefore not interstate commerce.

The government picked as the optimum case to take to the Supreme Court a dispute between the NLRB and Jones & Laughlin Steel Co., which had fired from its Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, plant 10 employees who wanted to join the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, subsequently refusing a NLRB order to rehire them. Jones & Laughlin insisted that since organizers were seeking to create a local union at the Aliquippa operation, their efforts involved no interstate commerce. Justice Department lawyers thought that an ideal test case because of the steel company’s nationwide impact. The country’s fourth largest steel business, J&L had 19 subsidiaries. These units not only milled steel and made steel products but mined ore and limestone and ran railroads, barges, and Great Lakes steamships; 75 percent of what J&L produced in Pennsylvania was shipped to fabricators elsewhere.

Jones & Laughlin proved to be the right case to persuade Hughes to switch sides. Ever since Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824 (“A Federal Take on Trade,” June 2019), the standard for whether the federal government could regulate local commercial activity was whether that activity directly affected interstate commerce. Hughes explained that the Wagner Act sought to obtain “industrial peace;” a strike at even one J&L plant would ripple nationally, disrupting the country’s steel supply. This aspect put the case well within congressional authority to regulate interstate commerce. In other words, the court expanded the Gibbons standard to include labor relations and other activities with even an indirect effect on interstate commerce.

his opinion for the five-justice majority in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin, Hughes went well beyond the steel industry’s centrality to the American economy. He “used the opportunity occasioned by the Wagner Act cases to set forth a grand restatement of the law,” said University of Notre Dame law professor Barry Cushman. Hughes wrote: “Although activities may be intrastate in character when separately considered, if they have such a close and substantial relation to interstate commerce that their control is essential or appropriate to protect that commerce from burdens and obstructions, Congress cannot be denied the power to exercise that control.” And he wasn’t hinging his argument on the sheer size of Jones & Laughlin. That day the court issued four other opinions, all upholding NLRB enforcement actions against smaller companies, including a men’s clothing manufacturer with a single plant in Richmond, Virginia.

The four dissenting justices—all of whom, like Hughes, had found the Recovery Act and bituminous coal acts unconstitutional—realized the broad implications of the majority opinion. They insisted that any effect exerted on interstate commerce by labor relations at a given plant was “indirect and remote in the highest degree” and said the Hughes approach established a “view of congressional power that would extend it into almost every field of human industry.”

Hughes’s about-face on the reach of the Constitution’s commerce clause came at a politically opportune time. Roosevelt, angered at the Recovery Act, coal, and other Supreme Court decisions dismantling pillars of his recovery plan, was pushing for legislation that would force older justices—mainly conservatives who voted against New Deal legislation—to retire or allow the president to enlarge the high court from nine justices to as many as 15. The decision in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin effectively ended that effort. Of the ruling, Washington Star columnist G. Gould Lincoln wrote, “The Supreme Court of the United States yesterday pulled the gimp [vigor] out of the demand for passage of President Roosevelt’s bill to increase the membership of the court.” Roosevelt himself saw the ruling that way, saying of the decision, “It was political, purely, engineered by the Chief Justice.” Immediately after the NLRB decisions, Senator Burton K. Wheeler (D-Montana), leading foe of the “court packing” proposal, said, “I feel now there can be no excuse left for wanting to add six new members to the Supreme Court.” Twenty-six days after Hughes handed down the NLRB decision, the Senate Judiciary Committee rejected Roosevelt’s proposal for additional justices. Cynics called Hughes’s new expansionist interpretation of the commerce clause and the constitutionality of New Deal innovations “the switch in time that saved nine.”

Hughes deeply believed—and often stated—that one of his jobs as a justice was to maintain public confidence in the judiciary, to keep the Court’s prestige from being diminished by out-of-step decisions—”self-inflicted wounds,” he called them—such as the 1857 Dred Scott decision holding that Negroes could not be American citizens or an 1885 declaration that a federal income tax was unconstitutional. But Hughes staunchly maintained that such concerns did not impel his vote upholding the National Labor Relations Act. “The court acted with complete independence,” he insisted in autobiographical notes intended primarily for his grandchildren and dictated in the early 1940s after his retirement from the bench. He asserted that the 1937 opinions he wrote “were in no sense a departure from the views I had long held and expressed.” As evidence of judicial continuity, he cited a 1911 decision upholding an Iowa statute stopping railroads from forcing on workers employment provisions limiting their ability to collect damages for on-the-job injuries—a decision that showed his sympathy for labor but in no sense involved the right of Congress to regulate interstate commerce.

Certainly Jones & Laughlin and the four other NLRB decisions released that April day gave a big boost to workers, opening the way for judicial approval in coming years of laws mandating unemployment compensation and barring shipment of goods made under substandard labor conditions. But those rulings’ impact reached well beyond labor relations. According to Cushman, “the claim that the Wagner Act cases marked a reversal (or a substantial departure from) the Court’s earlier commerce clause jurisprudence has been accepted with near-unanimity by the historical community.” The significantly expanded reading of the commerce clause green-lighted Congress to, for example, limit how much grain a farmer could raise for his own use, ban racial discrimination in any place of public accommodation that serves visitors from another state, and ban lenders from using “extortionate means” to collect debts. In fact, for 18 years after the 1937 NLRB decisions, every time the justices considered a case claiming that Congress had stretched its authority over interstate commerce too far, they upheld the statute in question.

This SCOTUS 101 column appeared in the June 2020 issue of American History.