‘They beat against the houses, swarm in at the windows, cover the passing trains. They work as if sent to destroy’

Late one July morning in 1874, 12-year-old farm girl Lillie Marcks watched the sunlight dim and a peculiar darkness sweep over the Kansas sky. A whirring, rasping sound followed, and there appeared, as she later recalled, “a moving gray-green screen between the sun and earth.” Then something dropped from the cloud like hail, hitting her family’s house, trees and picket fence. A child in Jefferson County, Kansas, who had gone out at midday to draw water from the well exclaimed: “They’re here! The sky is full of ’em. The whole yard is crawling with the nasty things.” A settler in Edwards County, Kansas, reported: “I never saw such a sight before. This morning, as we looked up toward the sun, we could see millions in the air. They looked like snowflakes.” What this Kansas trio saw that summer was also observed by others statewide and across Dakota Territory, Montana Territory, Wyoming Territory, Colorado Territory, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and Texas. What Marcks described as “a moving, struggling mass” of grasshoppers—technically, Rocky Mountain locusts (Melanoplus spretus)—had invaded the Great Plains.

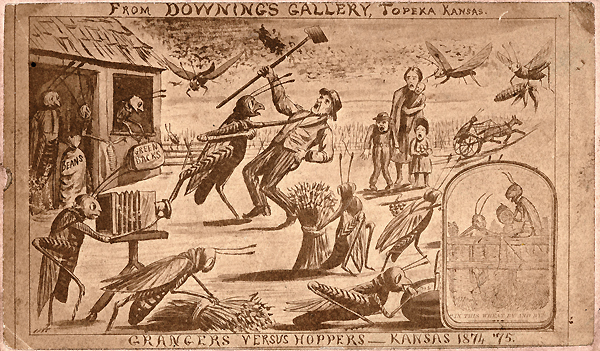

Farmers, their pants legs cinched with string, ran to cover their valuable wells. In many cases their drinking water was about the only thing they could save. As the swarms landed on houses, fields and trees, the skies cleared, but then the real devastation began. The locusts soon scoured the fields of crops, the trees of leaves, every blade of grass, the wool off sheep, the harnesses off horses, the paint off wagons and the handles off pitchforks. They washed in waves against the fences, piling a foot or more deep. They feasted for days, even devouring the clothing and quilts farmhands threw protectively over the vegetable gardens. Livestock feasted on the locusts, and farm families killed many of the invaders by building bonfires. But there were just too many of the “nasty things” for man or beast to control. The locusts, farmers grimly quipped, “ate everything but the mortgage.”

Taxonomically speaking, locusts and grasshoppers are the same. When these insects are nonmigratory and nondestructive, with a low-density population, they are considered grasshoppers. When they are both migratory and destructive, with a high-density, concentrated population, they are considered locusts. The particular locusts that caused $200 million in crop damage across the Great Plains in 1874—temporarily stalling Western migration and forcing many homesteaders either to return east or to move farther west—seemed ubiquitous on the frontier at that time.

Rocky Mountain locusts normally ranged along the high, dry eastern slopes of the Rockies, from the southern tip of British Columbia forestland down through the territories of Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and western Dakota. As the summer heated up, they hatched from egg pods laid in the ground the year before. The species was given to rapid population increases. When such increases coincided with die-offs of their natural vegetation, usually due to drought, the locusts used their large wings to migrate to lower, more fertile regions in search of food. In 1874 some 120 billion locusts cut a swath more than 100 miles wide that by fall had advanced to Texas.

The Homestead Act of 1862, the end of the Civil War in 1865 and completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 contributed to a great Western migration of Americans. These homesteaders sought a fresh start on free land but sometimes got more than they bargained for in bad soil or drought and had trouble scraping a living from the prairie. Although few of them could have been prepared for what happened in 1874, locust (or grasshopper) infestations were hardly a novelty in North America. The history of Jesuit missions in California speaks of locust plagues there as early as 1722. Locusts had also repeatedly hit Eastern farms, ravaging, for example, Maine in 1743 and 1756 and Vermont in 1797–98. Period accounts from the West record significant infestations in 1828, 1838, 1846 and 1855, but the dates and severity varied by area. Minnesota, for example, also experienced infestations in 1856, 1857 and 1865. Nebraska was infested in 1856 and then six more times over the next 17 years. Most localized attacks proved irritating but not disastrous. The widespread winged invasion of 1874, though, hit harder than a ton of flying bricks.

Farmers on the Great Plains had already weathered the economic Panic of 1873, the unusually hard winter of 1873–74 and the dry, almost droughtlike early summer that followed. But most had not given up hope. They scanned the skies daily, looking for signs of the rain that would revive what crops had not already succumbed to the drought. What eventually swept in was something very different. The hot and dry conditions of the spring and summer of 1874 had provided ideal breeding conditions for the Rocky Mountain locusts. “The grasses seemed to wither, and the cattle bunched up near the creek and the well, and no air seemed to stir the leaves on the trees,” Kansas pioneer Susan Proffitt wrote. “All nature seemed still.” And then they came.

“They looked like a great, white glistening cloud, for their wings caught the sunshine on them and made them look like a cloud of white vapor,” one unsettled pioneer wrote. “It seemed as if we were in a big snowstorm,” recalled another, “where the air was filled with enormous-size flakes.”

In places the mass of insects blocked out the sun for as long as six hours. When the locusts did descend, they covered every shrub, plant and tree, sometimes breaking limbs with their combined weight. They flattened and devoured corn stalks and reaped fields of grain. They consumed only the most succulent bits of the wheat crop, letting the rest rot on the ground. “Wheat and grasshoppers could not grow on the same land,” one forlorn homesteader put it, “and the grasshoppers already had the first claim.” The locusts picked clean whole watermelon patches and stripped fruit trees, leaving peach pits dangling from empty branches.

Having ravaged the fields and trees, the locusts then invaded the farmers’ houses, clearing out barrels and cupboards and devouring anything not secreted away in wood or metal containers. They even shredded curtains and clothing. At night farm families had to shake bedding to dislodge grasshoppers before retiring and considered themselves lucky if another shaking was not needed before morning. “The air is literally alive with them,” a New York Times correspondent wrote from Kansas. “They beat against the houses, swarm in at the windows, cover the passing trains. They work as if sent to destroy.”

Terrified children fled before the swarms, and one Kansas pioneer wrote of a “young wife, awaiting her first baby, in the absence of her husband…[who] had gone insane from fright.” Kansan Adelheit Viets claimed to have had the clothes literally eaten off her back. “I was wearing a dress of white with a green stripe,” she recalled. “The grasshoppers settled on me and ate up every bit of the green stripe in that dress before anything could be done about it.”

A map produced by the state of Missouri shows that the 1874 infestation spread from the eastern slope of the Rockies into western Iowa, Minnesota and Missouri and from the Canadian Prairie provinces to central Texas, just north of Austin. Generally it moved from north to south. Hit particularly hard were Kansas, Nebraska, Dakota Territory, western Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Indian Territory, eastern Colorado Territory and the southeastern corner of Wyoming Territory. The results were often magnified in remote areas, as settlers there had modest food reserves and few neighbors to help. Texas, Montana Territory and the Prairie provinces of Canada were affected but escaped the worst of the infestation. The largest locust swarm in 1874, according to an 1880 U.S. Entomological Commission report, “covered a swath equal to the combined areas of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Vermont.”

Amateur estimates from the period yielded similar results. In June 1875 Albert Child, a county judge and sometime meteorologist in Plattsmouth, Neb., observed one huge swarm as it passed overhead. By telegraphing for reports from surrounding towns and timing the rate of movement as the insects streamed by for five days, he estimated the swarm was some 1,800 miles long and 110 miles wide. Based on this data he calculated that it covered an astonishing 198,000 square miles. The locusts of 1874, by comparison, infested an estimated 2 million square miles.

As fall neared and colder weather set in, the locusts often collected on railroad tracks, which absorbed the heat of the sun by day and retained it well into the night. The early morning chill found the slumbering insects stiff and unable to move from the path of passing trains. The resulting slippery, gooey mess made it difficult for the trains to safely negotiate grades.

Settlers tried to repel or destroy the locusts by lighting fires and exploding gunpowder charges in their fields, blasting the swarms with shotguns and sometimes simply wailing away at them with wood planks and farm implements. Lillie Marcks’ father and a hired man tried to halt the invaders’ advance by digging a trench along their fence line, filling it with sticks and leaves and starting a fire, only to watch helplessly as the sheer mass of insects smothered the flames. “Think of it,” Lillie wrote, “grasshoppers putting out a fire.”

Others farmers scoured their fields with a “hopperdozer.” This makeshift device comprised a sheet-iron scraper smeared with coal tar and pulled on runners by horses over the infested fields to harvest the bumper crop of locusts. The dozer worked to a degree, but only on flat ground, and even then it was inadequate to deal with the scope of the 1874 infestation. J.A. King, of Boulder, Colorado Territory, invented a horse-pulled suction machine that functioned like a latter-day vacuum cleaner, sucking locusts into a hopper and then a bag for easy disposal. But it, too, worked well only on flat ground, and crushed locusts often clogged its mechanism.

Ultimately, all defenses proved inadequate, as the locusts far outnumbered the humans. The invaders not only destroyed the natural and cultivated vegetation but also left behind the odor of their excrement, which turned ponds and streams brown and left the water wholly unfit for consumption by man or animal. Birds and animals resorted to eating the dead locusts, but the feast left barnyard animals bloated, their meat inedible.

One report released in 1874 suggested that just one family in 10 had enough provisions to last through the coming winter. To avoid starvation, many desperate settlers, especially in western Kansas and Nebraska, abandoned their homestead claims and their dreams of a new life to return east. Kansas alone lost as much as one-third of its population. Meanwhile, the flow of westbound emigrants to the Plains fell by as much as 20 percent.

Debts prevented some from leaving. Others were loath to cede their investments of time and energy. Still others had forged ties to the land they struggled to tame. “I have lost my all here,” one man wrote, “and somehow I believe that if I find it again, it will be in the immediate neighborhood of where I lost it.” Furthermore, he continued, “I have a child buried on my claim, and my ties here are stronger and more binding on that account.” Those who stuck it out often turned to federal and territorial governments for help, borrowed money from family and friends or even mortgaged their land.

Not everyone made it. A correspondent for the St. Louis Republican published the following report in June of what became known as the “Year of the Locust”:

We have seen within the past week families which had not a meal of victuals in their house; families that had nothing to eat save what their neighbors gave them, and what game could be caught in a trap, since last fall. In one case a family of six died within six days of each other from the want of food to keep body and soul together.…From present indications the future four months will make many graves, marked with a simple piece of wood with the inscription STARVED TO DEATH painted on it.

Reverting to an earlier time, some pioneers tried to feed their families by hunting. Other desperate souls survived by gathering discarded buffalo bones from the prairie, hauling them to railroad hubs and selling them for up to $4 per ton; buffalo horns fetched up to $8 per ton. According to period reports, in 1874 the amount of buffalo bone transported by the railroads was three times what it had been the year before and six times that of 1872.

Enter Charles Valentine Riley. The Missouri state entomologist noted that livestock and wild animals happily ate the locusts and that man had used the insect as food since ancient times. Riley thus proposed “entomophagy”—simply put, eating the bugs—as a way to reduce their numbers while nourishing hungry settlers. The insects, he insisted, yielded an agreeable nutty flavor when one removed their legs and wings and fried their bodies in butter. He added that the rendered locusts also made a palatable soup. To prove his point, Riley sent a bushel of scalded locusts to one St. Louisan caterer, who insisted he would have them on his menu every day if he could get them.

Hard-pressed pioneers gave Riley’s recipes a try. Gourmands claimed that locust coated in butter, fried and seasoned with salt and pepper tasted just like crawfish. Others elected to add their crispy locusts to broths and stews. But a number of settlers who had watched the locusts destroy their farms said they would just as soon starve as eat those horrible creatures.

More palatable help was forthcoming. As the scope of the disaster became clear, state and territorial governments held special legislative sessions, issued bonds to relieve the destitution and dispatched agents to the East to secure aid, particularly seed for the 1875 growing season. The nation responded with money and supplies, often hauled free of charge by the railroads. The federal government exempted those homesteaders hit hard by the locust infestation from residency requirements, enabling them to briefly leave their land (and perhaps relocate their families) to work elsewhere and recoup their losses without fear of losing their claim. Settlers were required to provide two witnesses to corroborate the destruction of their crop. The act provided for an extended leave should the locusts return in 1875. Homesteaders had to provide proof of resettlement upon their return. In January 1875 Congress also earmarked $30,000 to supply seed to the beleaguered areas.

The U.S. Army, with the organization and experience to deal with large-scale relief efforts and best situated to reach homesteaders in remote areas, offered the most help. During the bleak winter of 1874–75 its soldiers distributed thousands of heavy coats, boots, shoes, woolen blankets and other items, along with nearly 2 million rations, to suffering families in Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado Territory and Dakota Territory.

In the spring of 1875 the trillions of eggs locusts had laid the previous summer began to hatch, covering the ground in many places with a squirming, struggling mass of nymphs. Farmers feared the worst, but a late snowstorm and hard frost killed most of the immature insects, allowing farmers time to replant their crops.

The good news kept coming. Population declines following the 1874 locust infestation proved short lived. In Kansas, for example, the population stood at 364,400 in 1870 but within 10 years had risen to 996,100. Hoping to stop future infestations before they got started, Nebraska in 1877 passed a Grasshopper Act, requiring every able-bodied man between the ages of 16 and 60 to work at least two days eliminating locusts at hatching time or face a $10 fine. That same year Missouri offered a bounty of $1 a bushel for locusts collected in March, 50 cents a bushel in April, a quarter in May and a dime in June. Other Great Plains states made similar bounty offers. In the 1880s farmers had recovered sufficiently from their locust woes to be able to send carloads of corn to flood victims in Ohio. They also switched to such resilient crops as winter wheat, which matured in the early summer, before locusts were able to migrate.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Rocky Mountain locust was fast becoming extinct. The last reported sighting of a living specimen came in southern Canada in 1902. Why this particular species became extinct remains something of a mystery. Scientists have suggested the reduction in Indian populations and the settlers’ transformation of the land might have led to habitat changes that brought on the locusts’ decline. Others have cited the insect’s lack of genetic variety or connected the decline to the reduction of buffalo herds or the beaver population. New habitat-altering plants, an influx of insect-eating birds and farming itself (plowing destroyed untold millions of buried Rocky Mountain locust egg masses) are other factors that contributed to the eradication of the species. But don’t rest easy just yet. Such invasive insects as the Mormon cricket (actually a katydid) still thrive in the region and have threatened Western crops as recently as the summer of 2010.

Chuck Lyons, based in Rochester, N.Y., is a retired newspaper editor who now writes freelance articles for Wild West and other publications. Suggested for further reading: Harvest of Grief, by Annette Atkins; Pioneer Women: Voices from the Kansas Frontier, by Joanna L. Stratton; and The Locust Plague in the United States, by Charles Valentine Riley.