Polarized partisanship, deep animosity among candidates, worry about the peaceful transfer of power—sound familiar?

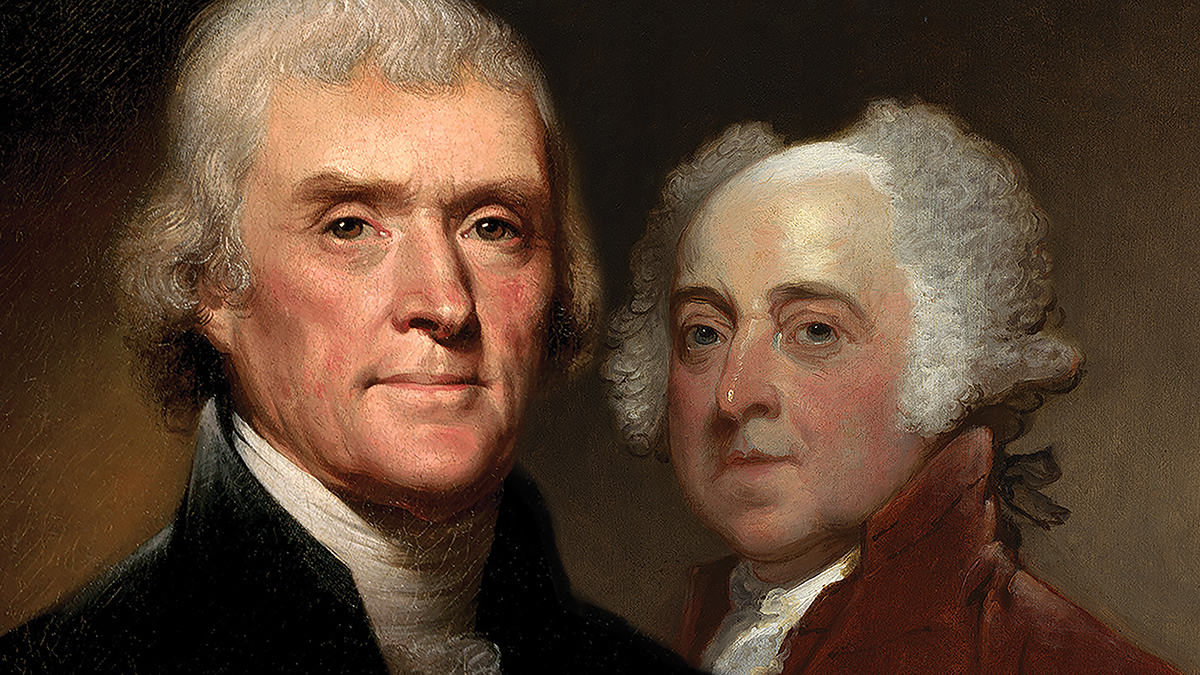

Among pivotal American episodes, the 1800 election occupies a central place. That race, labeled by Thomas Jefferson “the Revolution of 1800,” introduced to the world the modern political campaign as well as the peaceful transfer of power in a nation-state. Fittingly, that campaign’s key figures—Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and Aaron Burr—were larger than life. Jefferson, having served as Adams’s vice president since 1797, was challenging the incumbent for the presidency. The contest brought intense scrutiny to bear on the 1787 Constitutional Convention’s choice of how to select a chief executive. The result was less than ideal.

Debating extensively in 1787 about how to choose a president, virtually no delegates to the Constitutional Convention had supported the notion of having the people vote directly. Delegates decided to trust the choice of leader to a group of electors, men of stature to be chosen for this role in a manner decided by each state’s legislature.

This raised the issue of how many electors each state should field. Accustomed to the great sway that was accorded all states by the Articles of Confederation, smaller states feared a system that parceled out power according to population would cost them influence and protection. Hence the Convention’s decision that each state’s electors would equal in number the state’s representation in Congress—House membership plus two. Each elector was to vote for two individuals for president, at least one of those from a state other than the elector’s. The candidate receiving the majority of electoral votes would be president; whoever received the next highest number of electoral votes would be vice president. Electors had no means of distinguishing which choice they preferred for president and which for vice president.

An option was required should no candidate get a majority. While the delegates all expected George Washington to win by huge majorities—and in 1788 and 1792, he uniquely received every elector’s vote—they anticipated that normally no candidate would amass a majority. The solution that the Constitutional Convention embraced to address the absence of a majority was another effort to balance power between large states and small states. The founders expected electors to function as an elite nominating committee, with the House of Representatives choosing the president from among the top five vote-getters. In making this selection each state, regardless of congressional delegation size, would have one vote, to be determined by the majority of its delegation. Proportionally speaking, this gave small states significantly more power over the outcome. For example, Virginia with 19 representatives in the House would have one vote, as would Delaware, with its single delegate.

The idea of electors as an elite body proved impracticable, and quickly—the Framers had not accounted for the power of party loyalty. Once parties came into existence during the 1790s, electors were picked to support a given party’s choice, not to use their individual best judgment.

The decade preceding the Civil War aside, the last years of the 18th century may have been the most divisive in American history. Convinced the country’s fate rested on it winning and holding power, each party portrayed the opposition as dangerously, even fatally wrong. Despite that resemblance, there was no close equivalent to today’s party system. The Federalist party, which split into factions, one affiliated with John Adams and the other with Alexander Hamilton, eventually evolved into today’s Republican party. The original Republican party, represented by Jefferson and James Madison, evolved into the modern Democratic organization. Federalists tilted to the right; Republicans, to the left.

The most dramatic factor affecting America in the 1790s had been the French Revolution and its aftermath. Reading into that tumultuous sequence of events, Federalists concluded that unfettered democracy imposed a leveling faction that would lead to anarchy, atheism, and tyranny. Federalists saw the Republican party, and especially Jefferson, as head-over-heels Francophiles, little more than a French front openly hostile to the American government.

Relations between America and France descended to a nadir in 1798 following the XYZ Affair. In that international ruckus, French officialdom behaved so contemptibly toward ambassadors sent by President Adams on a peace mission that, for a time, war seemed inevitable. In the “quasi-war” which followed, Adams and the Federalists gained popularity and political power, putting Republicans on the defensive.

The Federalist-controlled Congress focused on two major domestic perils. One was an increase in the number of immigrants of questionable loyalty. The other was the growing power of the Republican press in an era in which newspapers basically functioned as party mouthpieces. Federalists regarded opposition papers’ attacks on government as scurrilous, even seditious. Consequently, in 1798 Congress passed, and President Adams signed, the very controversial Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Alien Acts lengthened from five to 14 years the period of residency required to qualify for citizenship. Under them, a president had authority to expel immigrants with roots in any country at war with the United States, as well as any immigrant he considered “dangerous.” The Sedition Act made a crime punishable by fine and prison of publishing “false, scandalous, and malicious” criticism of the government, the president, or Congress that might stir Americans to sedition. One supporter claimed to see abundant evidence of “the necessity of purifying the country from the sources of pollution.”

A Federalist editorial writer summarized that party’s position: “You who are for French notions of government; for the tempestuous sea of anarchy and misrule; for arming the poor against the rich; for fraternizing with the foes of God and man; go to the left and support the leaders, or dupes of the anti-federal junto. But you that are sober, industrious, thriving, and happy, give your votes for those men who mean to preserve the union of the states, the purity and vigor of our excellent constitution, the sacred majesty of the laws, and the holy ordinances of religion.” A Federalist pamphlet declared that Republicans “have made liberty and equality the pretext, whilst plunder and dominion has been their object.” One pamphleteer wrote that Republicans’ “democracy” would be little different from the French Revolution’s “Jacobin tyranny.”

Contrasting views of the French Revolution and its aftermath played a crucial role in the election of 1800. The Federalists championed Adams as their best chance of holding onto power and eventually selected South Carolinian Charles C. Pinckney for the vice presidential slot. The Republicans looked to their acknowledged leader, Thomas Jefferson, to head that party and eventually decided on Aaron Burr as his running mate.

Fearing no Republican figure as greatly as they feared Thomas Jefferson, Federalists spared no effort to castigate the Republican candidate as a “head in the clouds” philosopher whose impractical and naive ideas would wreck the country. Jefferson was too “theoretical and fanciful” to lead a growing confederacy, they said. Make him president of a college, perhaps. President of the United States? Never.

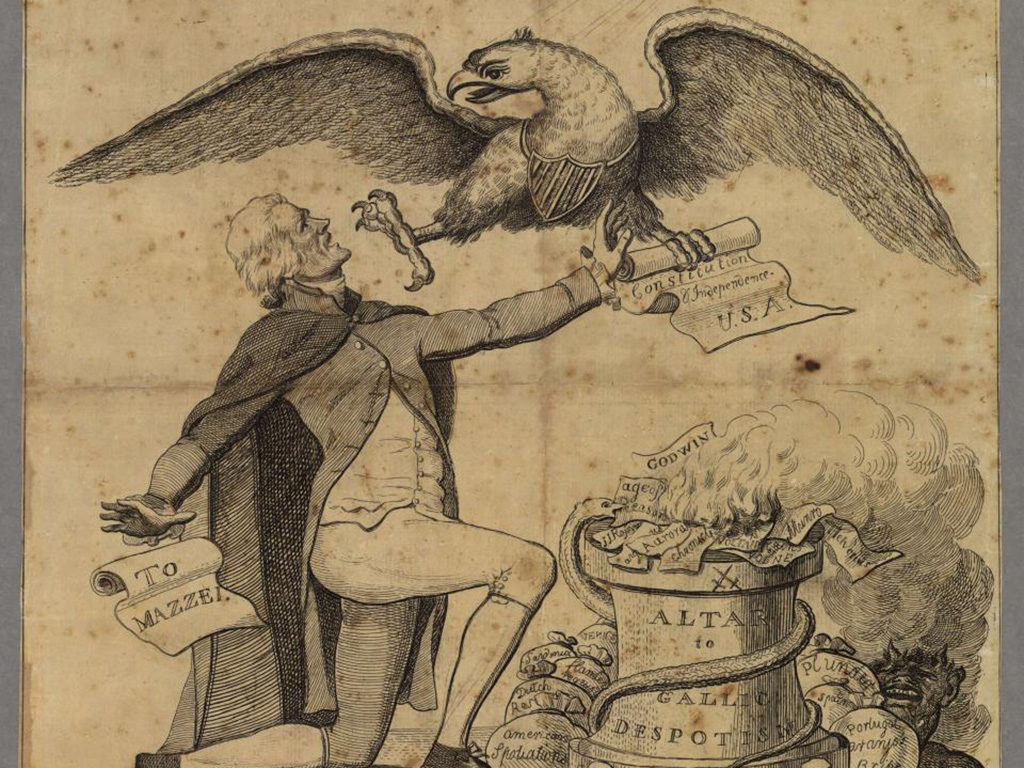

Reviving the infamous Mazzei letter as a campaign cudgel, Federalists reminded Americans that Jefferson had slandered their greatest hero. In April 1796, venting spleen about George Washington to a former neighbor, Philip Mazzei, in what he thought to be a private exchange, Jefferson had raged obliquely at the sitting president. “It would give you a fever were I to name to you the apostates [emphasis added] who have gone over to these heresies [against republicanism],” he wrote. “Men who were Samsons in the field and Solomons in the council, but who have had their head shaved by the harlot England.” Published in the United States in May 1797, the letter had embroiled Jefferson in a firestorm of criticism that the Federalists were happy to stoke again in 1800. Washington had been dead only a year, they argued; how could Americans elect a man who would malign him?

The most pervasive Federalist accusation was that Jefferson was an atheist. “Our churches may become temples of reason,” a pamphlet warned, invoking French revolutionaries’ label for deconsecrated sanctuaries. “Our Bibles cast into the fire.” “Those morals which protect our lives from the knife of the assassin—which guard the chastity of our wives and daughters from seduction and violence will be jettisoned,” trumpeted another broadside. “Murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will be openly taught and practiced,” a partisan said. “And the soil will be soaked with blood and the nation black with crimes.” “Every American must lay his hand upon his heart and ask, whether he continues in allegiance to “GOD AND RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT; or impiously declare for JEFFERSON AND NO GOD!!!” read a headline.

Republicans counterattacked. “Federalism was a mask for monarchy,” the newspaper Aurora declared. In Republicans’ eyes, Federalists differed little from Revolutionary-era Loyalists as foes of the new nation. Jefferson saw in the Sedition Act a first step toward ending the American experiment in republicanism and establishing a monarchy.

Alleging Sedition Act violations, the Federalists shut down newspapers and jailed journalists. One imprisoned publisher, Vermont Congressman Matthew Lyon, became so prominent a symbol of Federalist oppression that in 1798 he won re-election from behind bars.

Besides creating a standing army, the Federalist crackdown illustrated President Adams’s despotic disregard for individual liberty, Republicans said. Adams and his Federalist gang, they claimed, were spurning the principles of 1776—seeking war with France, cosseting the rich and established churches, victimizing immigrants, and increasing public debt and taxes. As president, supporters said, Jefferson would tax less, spend less, and do less, leaving people freer, especially in worshipping as they chose.

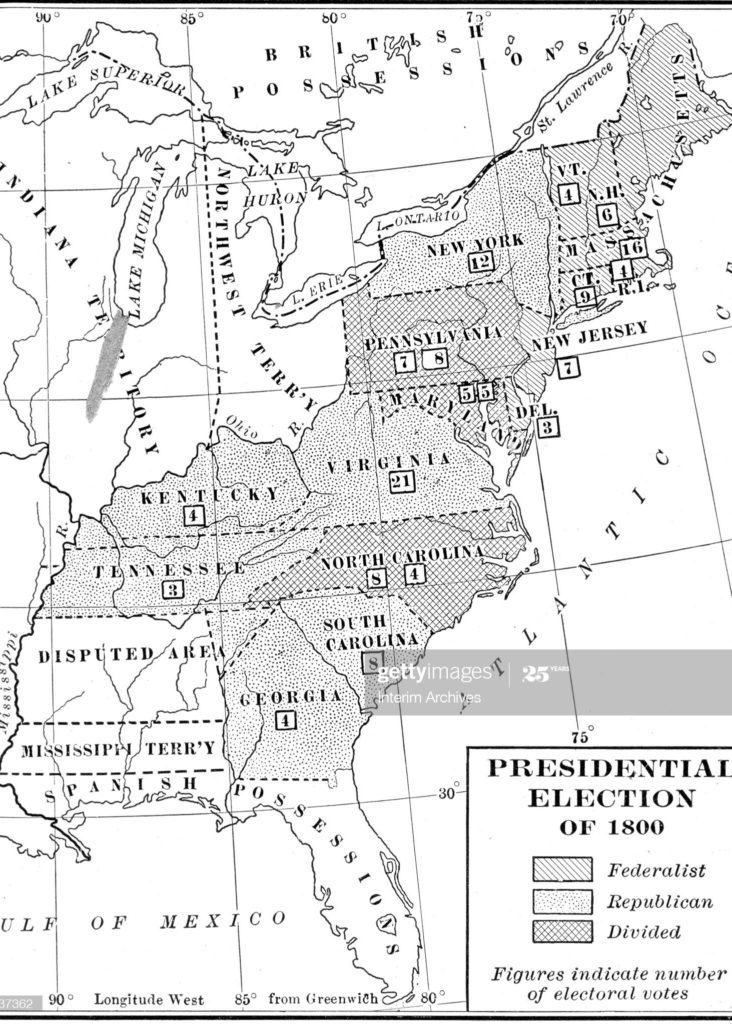

To win in 1800, the magic number was 70 electoral votes. In 1796, Adams had narrowly defeated Jefferson, 71-68; thanks to the system of split voting, Jefferson became Adams’s vice president. Planning for 1800, Republicans analyzed where Adams had gotten those 71 votes, calculating which states were ripe for flipping. Northern states were solid for Adams; the South, except perhaps Pinckney’s South Carolina, was solid for Jefferson. The middle states were key. In 1796 Adams had carried a vote each from Republican states Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina. Had two of those votes gone to Jefferson, he would have been president. To help ensure its native son’s victory in 1800 by getting him all 21 Virginia electoral votes, that state’s legislature changed its rules. Now a single statewide election was to choose electors. This tactic eliminated any possibility of Federalists casting electoral votes in Virginia.

The other crucial takeaway from 1796 was that the Federalists had carried all 12 New York electoral votes. If the Republicans could sweep New York or pry away at least some New York electoral votes, Jefferson likely would win. To that end, Republicans tried to have New York choose electors by district vote, instead of by the legislature. That effort failed. The Republicans’ only remaining hope was to win control of the New York legislature, a feat that rested on winning New York City, historically a Federalist enclave controlled by Alexander Hamilton.

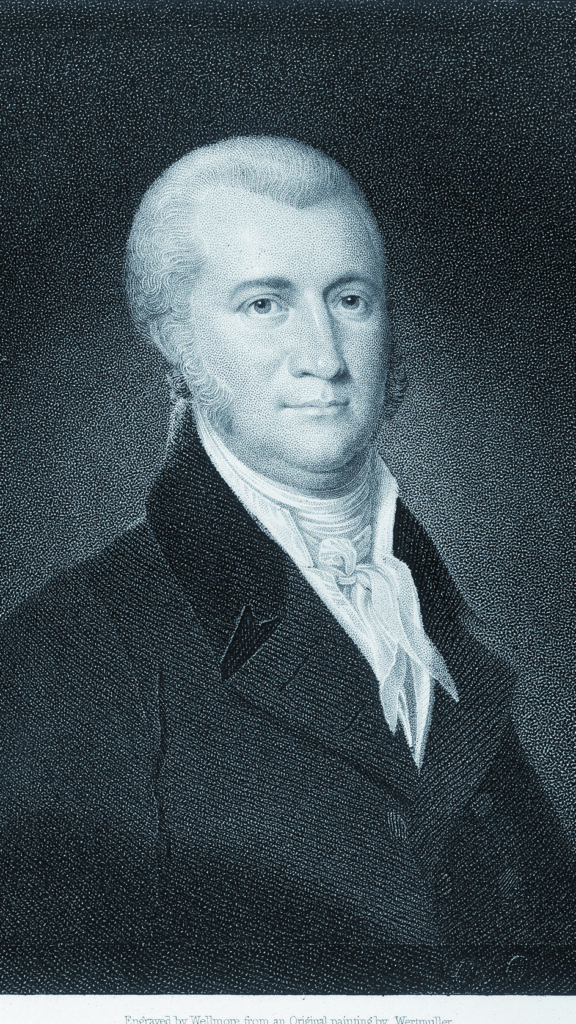

Enter New Yorker Aaron Burr, a man of great intellect, charm, and political acumen—arguably America’s first modern politician. “He possessed in a preeminent degree the art of fascinating the youthful,” a contemporary wrote. Few fellow politicians fully trusted Burr. Many actively disliked him. However, not a one doubted his influence over New York City politics. With a singleness of purpose that awed friend as well as foe, Burr, intent on becoming vice president, worked tirelessly to carry New York City for the Republicans in the April 1800 state elections.

In an age that expected demurely self-effacing candidates, Burr politicked robustly. Against Hamilton’s lackluster list, he recruited a stellar slate, including ex-governor George Clinton and Horatio Gates, a hero of the Revolution.

On election day, Burr wrangled a remarkable vote-getting push, especially in quarters thick with immigrants. The city’s poorest political district, the 6th Ward, comprising the mostly unsettled part of Manhattan Island above what is now Canal Street, made the difference. Immigrant voters tipped the scale. The legislature that would determine New York’s 12 electoral votes now was controlled by the Republicans, whose caucus had nominated Jefferson for president and Burr for vice president. Those men would oppose Adams and Pinckney.

New York was a critical but not necessarily essential state. The other keys were South Carolina and Pennsylvania. The situation in Pennsylvania was complicated. Republicans completely controlled the House; Federalists narrowly ran the Senate. A compromise, very unsatisfactory to the Republicans, eventually gave Jefferson an 8-7 victory. To take the White House, the Republicans needed to take South Carolina.

Matters in South Carolina also were confused. Charles Pinckney, who had fought in the Revolution, was the older brother of the well-regarded and well-connected Federalist Representative Thomas Pinckney, who had run as Adams’s No. 2 in 1796. The elder Pinckney, popular in his home state, was likely to pull some electoral votes there. If South Carolina went for Jefferson and Pinckney, Pinckney might end up president—a fervent desire of Alexander Hamilton, who believed C.C. Pinckney to be more susceptible to his arguments than the strong-willed and independent Adams. Hamilton, backed by the party’s conservative wing—sometimes called “Ultras” or “High” Federalists—viewed Adams’s overtures to France and fresh peace negotiations as a disastrous election-year mistake. Indeed, Hamilton so profoundly despised Adams that at one point he was heard to declare that he would rather see Jefferson win—in that case, he said, at least a man would know who his enemy was.

In October, Hamilton articulated his animosity in a scathing message that circulated among Federalist leaders. The document went viral, pre-industrial style, when the Aurora printed it. Hamilton derided Adams as mentally unstable and unfit to serve, excoriating the incumbent for showing “extreme egotism,” “distempered jealousy,” “ungovernable temper,” and “vanity without bounds.” Though probably not a deciding factor in the election, the communique cost Hamilton dearly in party influence and status.

Among the 16 state legislatures, whose votes had to be in by December 3, South Carolina’s 151-member body voted last, convening November 24, 1800. Each party ran eight electors; of those 16, legislators were to vote for eight. Some electors seemed poised to vote for Jefferson and for Pinckney. However, Pinckney, acting out of a sense of honor and anger at Hamilton’s epistolary tirade, said he wanted only support from men who would vote both for him and for Adams. Ultimately, the legislators chose all eight electors pledged to Jefferson and Burr.

As word was spreading about the South Carolina result, Jefferson seemed certain to beat Adams—until a disturbing wrinkle intruded. In instructing their slates, the Republicans had not made clear which elector was to vote for Jefferson and which was to vote for someone other than Burr. Thanks to this grievous oversight, Jefferson and Burr tied at 73 votes. Adams got 65; Pinckney, 64. John Jay received one vote.

Each of the 73 electors had intended Jefferson to be president and Burr to be his vice president but had not been able to so specify. Under the Constitution, an electoral-vote tie clearly bounced the choices of president and vice president to the U.S. House of Representatives. In the general election, control of the House had gone to the Republicans—but not until after the incoming Congress was sworn in the following year. The lame-duck body that was going to be deciding the 1800 presidential election had more Federalists than Republicans. Almost all of the Federalist congressmen interpreted the constitutional mandate to mean that they were to use their best individual judgment to pick the man they believed most suited to be president, not to do the will of the majority. To these Federalists, the unexpected tie vote offered a heaven-sent opportunity to fence Thomas Jefferson out of the White House.

One prominent Federalist disagreed. Alexander Hamilton’s strong loathing for Aaron Burr trumped the enmity he felt toward Jefferson, and Hamilton worked ferociously to convince fellow Federalists not to vote for Burr, whose personal ambition Hamilton saw posing a fatal risk to the new nation. “As to Burr, there is nothing in his favor,” Hamilton wrote. “His public principles have no other spring or aim than his own aggrandizement . . . I take it he is for or against nothing but as it suits his interest or ambition . . . Burr loves nothing but himself . . . He is sanguine enough to hope everything—daring enough to try anything—wicked enough to scruple nothing…if we have an embryo Cesar in the United States it is Burr.”

Hamilton’s protestations exerted minimal impact. Theodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts, Federalist speaker of the House, acknowledging Burr’s flawed character—besides loving power, “he is ambitious, selfish, profligate”—nonetheless said Burr should be president, observing him to be well bred and bereft of “pernicious theories,” Sedgwick said. “His very selfishness prevents his entertaining any mischievous predilections for foreign nations,” he added. Additionally, Sedgwick argued, in order to be able to govern effectively, Burr would need to engineer Federalist support, obtainable only by acceding to Federalist views.

Despite laying claim to a lame-duck majority, House Federalists did not control a sufficiency of states to elect Burr. With 16 states in all, the winning number was nine.

Jefferson and the Republicans held eight states—New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Adams and the Federalists had six—New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, and South Carolina. Two delegations—Maryland’s and Vermont’s—were divided.

When the House met in Washington, DC, the new capital, in February 1801, to choose a president, the first ballot was eight for Jefferson, six for Burr, and two divided. The same occurred on the second ballot and the third, and through a week of more than 30 ballots.

Speculation arose about what might happen if the election had not been decided by March 4, when by law a president was to be inaugurated. Rumors swirled of assassination plots, arson schemes, military preparations, revolution, and nascent civil war. A Republican newspaper wrote, “Usurpation must be resisted by freemen whenever they have the power of resisting,” Jefferson warned Adams to expect “resistance by force and incalculable consequences.”

Aaron Burr’s role in the crisis is murky. There is no evidence that Burr offered anything specific to Federalists in exchange for their support. But neither did Burr emulate Pinckney’s statesmanly stance in South Carolina and remove himself from contention.

Instead, once it was clear that there was to be a tie, Burr declared to a Jefferson ally that he would accept the presidency if offered. He could become president only if some Republicans decided to vote for him to avoid a crisis. Had Burr openly sought those politicians’ support, he would never have received it. He followed the best course open to him, despite the fact that none of the electors wanted him to win.

To win, Burr needed three votes; Jefferson, one. Moderate Federalist James Bayard, a champion of Hamilton’s financial program, including the establishment of a national bank, was Delaware’s sole delegate. If Bayard were to switch his vote, Jefferson would have nine states and the presidency. In a long, passionate letter, Hamilton lobbied Bayard, not only savaging Burr but backhandedly endorsing Jefferson. “I admit his politics are tinctured with fanaticism. . . that he has been a mischievous enemy to the principle measures of our past administration, that he is crafty & persevering in his objects, that he is not scrupulous about the means of success, nor very mindful of truth, and that he is a contemptible hypocrite,” Hamilton wrote, balancing that harsh portrait by observing that Jefferson was no zealot but rather inclined to temporizing. A man of character, Jefferson would not ruin the financial system, making him by far the better of two bad choices, Hamilton maintained.

Bayard, fearful of seeing the stalemate drag on, conveyed to Jefferson that his vote depended on certain guarantees, such as that Jefferson would not undermine the bank and that he would leave in place individuals Bayard had placed in government jobs.

Did Jefferson make concessions? Maybe.

At any rate, Bayard pronounced himself satisfied. He withheld his vote, as did Federalists in Maryland and Vermont, giving Jefferson 10 states—without a single Federalist who voted for Burr actually changing his vote to Jefferson. The logjam broke, and after 36 ballots the House elected Thomas Jefferson the third president of the United States.

The American presidential election of 1800 had not been pretty at all. The balloting almost didn’t occur, and events came close to triggering violence. However, for the first time in history a nation saw power pass peacefully from one political party to its opponents, beginning an American tradition that has persisted even in the midst of civil war.