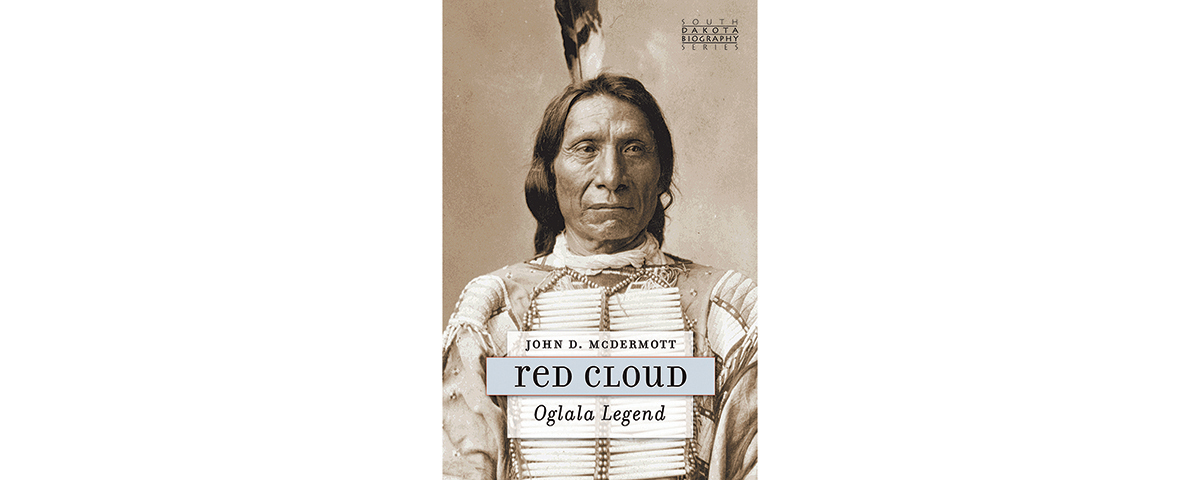

Red Cloud: Oglala Legend, by John D. McDermott, South Dakota Historical Society Press, Pierre, 2015, $14.95

Warrior extraordinaire Crazy Horse might be viewed as the “Rebel Red Man With a Cause,” and fighter turned holy man Sitting Bull certainly earned more than his share of “Red Badges of Courage,” but Red Cloud was arguably above all his fellow Lakotas when it came to defending his people’s interests and resisting the U.S. government.

“Unlike other great Lakotas such as Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, Red Cloud did not surrender, die young or flee his country into exile,” writes John McDermott in his concise, well-researched fourth book in the South Dakota Biography series.

Early on Red Cloud (1821–1909) achieved renown as a warrior by fighting such traditional enemies of his people as the Crows and Pawnees. In the 1860s conflict since dubbed Red Cloud’s War, he showed the Army he was a both a fine strategist and a master of guerrilla warfare, ultimately convincing the federal government to close the Bozeman Trail (which ran from the Oregon Trail near Fort Laramie to the Montana goldfields) and abandon Forts Reno, Phil Kearny and C.S. Smith.

The Oglala leader employed diplomacy as well as force, and after signing the Treaty of Fort Laramie on Nov. 6, 1868, he won recognition as principal chief of all the Sioux tribes. As McDermott points out, however, that treaty was a strategic victory for the whites, “because it set the stage for the eventual dispossession of the Sioux.” For the remainder of his long life Red Cloud sought “to ameliorate Euro-Americans’ impacts on his people.” On a visit to Washington in 1870 he lobbied for Lakota rights and impressed many people. But he could do little to stop the influx of white miners into the Black Hills once gold was found there in 1874.

His fighting days were over by the time of the June 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn, and while he sympathized with the Ghost Dancers in 1890, he did not join them. In his later years he mostly “battled” Indian agents on the reservations and politicians in Washington.

“He believed that the Great Spirit had created both Indians and other faces, but Indians were created first in the place where they lived, and it belonged to them,” McDermott writes. The author portrays Red Cloud as a courageous warrior, charismatic leader, skilled negotiator and farsighted chief but also an exceptional procrastinator who could at times be petulant, unreasonable and incomprehensible.

While McDermott provides a fine overview of Red Cloud in these 194 pages, those wanting further details should read the author’s two-volume Red Cloud’s War: The Bozeman Trail, 1866–1868, Robert W. Larson’s solid biography Red Cloud: Warrior-Statesman of the Lakota Sioux and Autobiography of Red Cloud, War Leader of the Oglalas, edited by R. Eli Paul.

—Editor