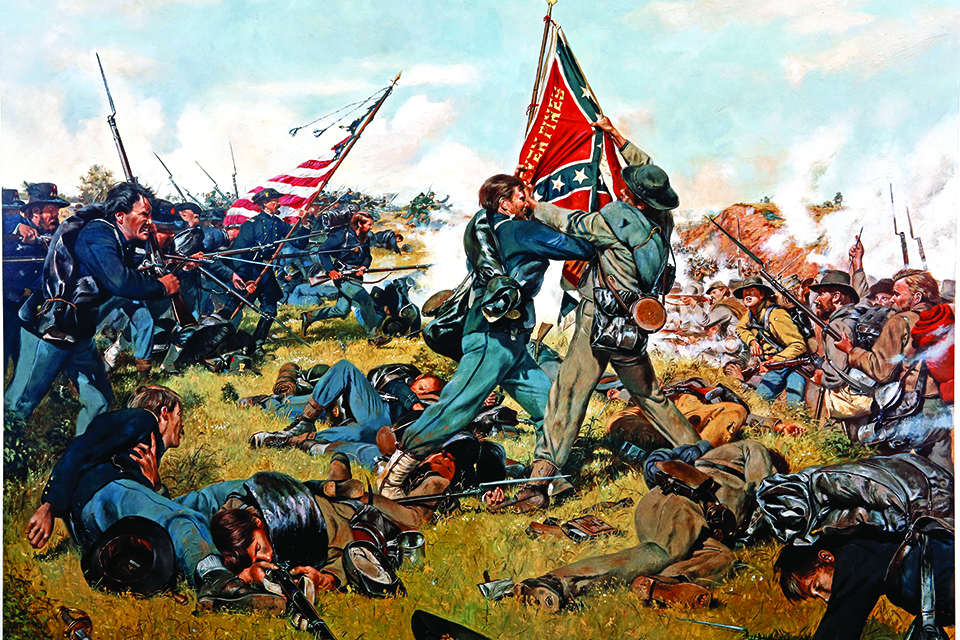

For every Joshua Chamberlain there was a soldier, blue or gray, whose bravery was overlooked

Popular lore and legend about the Battle of Gettysburg are peppered with heroic figures immortalized in countless books and articles, and, of course, movies. While the glory for those three days in July 1863 most often goes to well-known generals or civilian saviors who supported troops on both sides of the cause with muskets, meals, or medicine, there are any number of more obscure officers and common soldiers who performed gallant acts of lesser profile. America’s Civil War asked a select group of licensed battlefield guides at Gettysburg National Military Park to share the story of one of those men of their choosing. In alphabetical order, their selections follow. They include men who displayed not only courage, but also character, and include officers who rallied in the thick of the battle as well as officers whose valiant efforts in smaller skirmishes out of sight of the main event often get brushed aside. Whether singlehandedly capturing the enemy’s colors under fire, steadfastly refusing to retreat from untenable circumstances, or stoically leading weary troops across treacherous terrain and into murderous gunfire, all of these men acted to further the cause of their fighting army. They sacrificed their own interests, and in some cases, their own lives, for the greater purpose of the country they were fighting for, and they deserve a hero’s recognition.

Brigadier General Henry Lewis Benning

Benning’s Brigade, Hood’s Division, Longstreet’s Corps

Brigadier General Henry L. Benning, namesake of today’s well-known U.S. Army fort in Columbus, Ga., did not deliver a perfect performance at Gettysburg. During the July 2 fighting against the Union left, he essentially failed to follow the brigade he was supposed to

trail during the assault by Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division across the Emmitsburg Road and through the Peach Orchard, leaving part of his brigade dangling and in danger of being captured. Also, as is true for many other Confederates at Gettysburg, his performance did not produce a Southern victory.

I firmly believe, however, that the deeds of “Old Rock” Benning and his four regiments of Georgians at Gettysburg are underappreciated. After all, Benning skillfully advanced his brigade over the most difficult terrain Gettysburg had to offer. He inspired his men during their deadly advance, kept his units together (even accepting some Texans into his ranks), and tipped the scales for the Confederates in capturing Devil’s Den for the second time. When his own men tried to claim capture of some cannons at Devil’s Den, Benning gave credit to the other units that deserved it. During a Union countercharge, Benning displayed his ferocity on combat: “[H]old your fire until they come right up. Then pour a volley into them, and if they don’t stop, run your bayonets into their bellies.”

Fighting savagely in areas of the battlefield now known as the Slaughter Pen, the Valley of Death, and Devil’s Den, it is not surprising that Benning’s men suffered the highest percentage of loss among the brigades in Hood’s Division. Benning lost two of his colonels, killed in the Slaughter Pen and in the Triangular Field. Also, on July 3, his brigade bore the greatest part of the Union advance after the conclusion of Pickett’s Charge.

Ten weeks after fighting in the Civil War’s bloodiest engagement, Benning and his men fought in the war’s second costliest battle at Chickamauga. In between these terrible battles, 600 miles apart, Benning managed to secure official reports from the commanders of all four of his Gettysburg regiments and submitted a detailed one of his own. That all-too-rarely accomplished feat allows us to better understand America’s greatest battle, which warms this historian’s heart and earns Benning a coveted spot among Gettysburg’s “unsung” heroes.

–Garry Adelman Guide #110, licensed 1995

Color Sergeant Henry C. Brehm

149th Pennsylvania Infantry

Colonel Roy Stone’s “Bucktail” Brigade, composed of the 143rd, 149th, and 150th Pennsylvania, spent the night of June 30, 1863, in camp near Marsh Creek, Pa., six miles south of Gettysburg. Attached to the 3rd Division in Maj. Gen. John Reynolds’ 1st Corps, the brigade quietly began moving toward Gettysburg the morning of July 1, with Color Sergeant Henry C. Brehm of the 149th Pennsylvania carrying the

national flag. Upon reaching the Emmitsburg Road, on the outskirts of Gettysburg, the brigade heard sounds of battle. Pressing forward at the double-quick, the men reached the vicinity of the Lutheran Seminary at approximately 11 a.m., and then marched obliquely across the fields west of the seminary to the McPherson Farm. Major General Abner Doubleday, commanding the 1st Corps following Reynolds’ death earlier that morning, placed Stone’s Pennsylvanians between the 1st Division brigades of Brig. Gens. Solomon Meredith and Lysander Cutler. In the 149th, seven companies took a position facing west in a farm lane; three others faced north along the Chambersburg Pike.

Confederate artillery from the north soon enfiladed the position. As companies shifted toward the Chambersburg Pike to avoid the barrage, Rebel cannons to the west—on Herr’s Ridge—continued the onslaught of fire. Realizing his position was becoming untenable, Stone ordered the 149th’s color guard into a field just north of the pike. The ruse worked! Hunkering down behind a pile of fence rails, with only their flags exposed, Brehm’s six-man guard attracted artillery fire and convinced enemy infantry that a regiment had occupied that position.

After several charges and countercharges, the Bucktails were forced to retreat. Unfortunately, no one told the 149th’s color guard, and Sergeant Brehm refused to leave without orders. Suddenly from the west, six Confederates rushed forward and grabbed for the flags. After a struggle, Brehm and his men ran toward their retreating regiment, only to find more men in gray. As Brehm raced through the line toward Seminary Ridge, he was hit in the back by a shell fragment and severely wounded. His flag was quickly seized by an enemy soldier.

Brehm died on August 9. Yet by buying precious time for his embattled brigade with his courage and leadership, he earned a place as one of Gettysburg’s unsung heroes.

–Therese Orr Guide #236, licensed in 2016

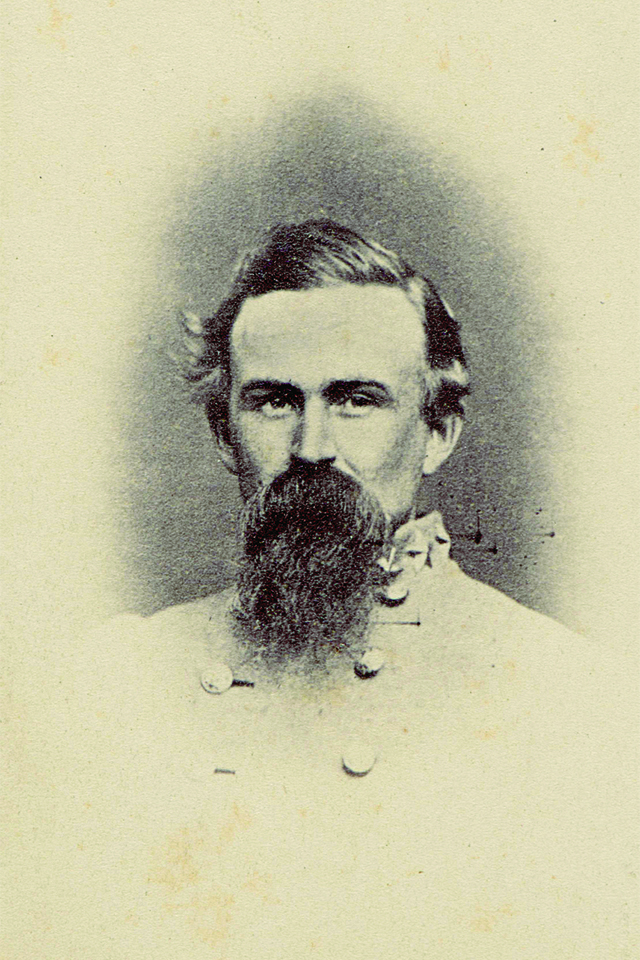

Brigadier General George P. Doles

Doles’ Brigade, Rodes’ Division, Ewell’s Corps

Although George Doles had just a common-school education and mere militia experience, he was highly regarded enough to be elected colonel of the 4th Georgia Infantry on May 9, 1861, not quite a month into the Civil War. Sixteen months later, on November 9, 1862, he was

promoted to brigadier general and assumed command of a brigade—eventually consisting of the 4th, 12th, 21st, and 44th Georgia Infantry—in Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’ Division in Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Second Corps. Doles performed admirably at the major Confederate victories at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and in May 1863 at Chancellorsville, where he lost 437 men. He was 33 years old, having served with distinction for two years in an army known for combat commanders.

On July 1, 1863, the first day of fighting at Gettysburg, Doles had orders to protect the left flank of Rodes’ Division and during the afternoon clashed with Union Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow’s 1st Division, part of Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s 11th Corps, on Blocher’s Knoll (known today as Barlow’s Knoll). Barlow got the upper hand but left his new position overextended. In response, Doles led an attack on the knoll from the northwest, joined by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon’s newly arrived brigade. When Colonel Wladimir Krzyzanowski’s 2nd Brigade, in Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz’s 3rd Division, suddenly swarmed in from the right, Doles wheeled the 21st Georgia to meet the attack. The regiment, however, was soon driven back to Blocher’s Lane.

Doles quickly shifted the 12th Georgia from the left to reinforce the hard-pressed 21st. Meanwhile, the rest of the brigade wheeled right and closed on the enemy, exchanging volleys at 75 yards. The Georgians’ marksmanship was devastating; within 15 minutes, Krzyzanowski lost more than 600 men. Belatedly, the 157th New York arrived to offer assistance, but in short order Doles had three regiments concentrated on the New Yorkers, who were soon repulsed with 75 percent losses. Doles’ Brigade suffered only 219 casualties—16 percent of those engaged.

On June 2, 1864, during the Battle of Cold Harbor, Doles was killed by a sharpshooter at Bethesda Church, Va. His remains were returned to Milledgeville, Ga., for burial.

Regrettably, he is not counted among the famous figures of Gettysburg. Although his brigade performed well, recognition never came—partly because Doles fought detached from, and largely out of sight of, his division commander, Rodes. To make matters worse, fellow Georgian Gordon claimed a great deal of the glory for Doles’ success that July day when he wrote his romanticized 1904 memoir, Reminiscences of the Civil War.

–David L. Richards

Guide #23, licensed in 1986

Colonel David Ireland

137th New York

A native of Forfar, Scotland, born in 1832, David Ireland was with the 79th Cameron Highlanders at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, and that fall was captain in the 15th U.S. Regulars. In the summer of 1862, he was named colonel of the new 137th New York Infantry, which saw its first combat at Chancellorsville in May 1863.

Two months later, on July 2, the 137th—part of Brig. Gen. George S. Greene’s 3rd Brigade, 12th Corps—found itself building entrenchments

on Culp’s Hill on the Union right. As fighting raged on the left, it remained relatively quiet for Henry Slocum’s 12th Corps until about 6 p.m., when he was ordered to lend assistance to the threatened Union positions in the Peach Orchard, Wheatfield, and on Little Round Top.

As the 12th Corps departed, Confederate Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s Division in Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Corps advanced on the vacated Union trenches. Only Greene’s all-New York brigade had been allowed to remain—1,424 men aligned from the summit of Culp’s Hill to Rock Creek. Johnson had 4,678 men, more than enough, and as the Rebels swarmed in, Greene attempted to occupy those trenches, too.

To Greene’s fortune, his largest regiment—the 423-man 137th New York—was on his right. Ireland’s men managed to reach trenches previously occupied by Brig. Gen. Thomas Kane’s 2nd Brigade just as the Confederates struck. Leading the attack on Greene’s right was Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart’s 2,100-man brigade.

With three Virginia regiments, the 1st Maryland Battalion, and elements of the 1st North Carolina Infantry on hand, Steuart soon learned that Greene’s right was unsupported. The 137th checked Steuart’s advance for a time, but when a Union regiment coming to Ireland’s assistance was driven off the field, the 137th was on its own. “At this time we were fired on heavily from three sides…,” Ireland recalled. “Here we lost severely in killed and wounded.”

Though virtually surrounded, Ireland was able to fall back to a traverse line that had been constructed earlier in the day, but he and his men quickly faced a renewed assault—the fighting at close quarters and desperate. Captain Joseph Gregg, Company I, was mortally wounded as his unit contested a threat with fixed bayonets. Again, the 137th somehow kept the Confederates at bay until help arrived. Its ability not to break against such unrelenting pressure, in fact, is one of Gettysburg’s unsung stories. Had the Federals on Culp’s Hill succumbed, the loss of this critical sector undoubtedly would have altered the battle’s outcome. (The 137th New York ironically suffered 137 casualties. It is interesting to note that the more famous bookend regiment, the 20th Maine on Little Round Top, endured the same percentage of loss—32.4 percent.)

Ireland did not survive the war, dying of dysentery in recently captured Atlanta on September 10, 1864. In a letter to Ireland’s wife, the attending physician wrote, “[H]is loss to the public service will with great difficulty, if at all, be supplied.”

–Charles Fennell Guide #28, licensed in 1986

Captain Francis Irsch

45th New York Infantry

The 11th Corps is probably best known for its role in the Army of the Potomac’s famous defeat at Chancellorsville in May 1863, as well as for the derogatory “Flying Dutchmen” nickname it garnered, in reference to the large number of German immigrants in its ranks.

Widespread prejudice in mid-19th century America held that Germans were poor material for soldiers, not to be counted on when the bullets began to fly. This, of course, was nonsense. More than 200,000 men of German origin served in the Union Army during the war—the most of any ethnic group—and many distinguished themselves fighting for their adopted land. Captain Francis Irsch’s service is of one of their stories.

Commander of Company D, 45th New York Infantry, Irsch was among the weary members of the 11th Corps making the march to Gettysburg the morning of July 1. Just 22, he was already a veteran of two major battles and several smaller engagements. His regiment, the corps’ vanguard, reached Gettysburg about noon and advanced rapidly through the town before halting for a brief break near Pennsylvania College. Irsch, however, would get no rest; he was ordered to assume command of four companies and advance as skirmishers to support the embattled 1st Corps. Advancing under heavy fire, the New Yorkers played a critical role in helping to defeat an attack by Colonel Edward O’Neal’s Alabama brigade, taking numerous prisoners.

Later that afternoon, the Federal positions north of town collapsed under a renewed onslaught. The 45th retired in good order down Washington Street but found its route blocked by retreating 1st Corps troops, with Confederate infantry in pursuit. In an attempted detour down Chambersburg Street, the regiment encountered Rebel forces in the town square. The only way out was through alleys alongside Christ Lutheran Church, which led to a courtyard with one narrow exit. As the enemy closed in, Irsch ordered his companies, at the rear, to occupy nearby buildings and fight it out. He also rounded up Federal stragglers and soon had the services of a few hundred men.

Under Irsch’s inspired leadership, resistance continued for much of the evening, with several Confederate surrender entreaties rejected. Finally, near dusk, he recognized the hopelessness of his situation and surrendered—after ordering his men to destroy their weapons and ammunition. Three days later, as the defeated Army of Northern Virginia prepared to retreat from Gettysburg, paroles were offered to the prisoners from the 45th. Irsch refused, believing that his men’s presence during the retreat would greatly hinder the Confederates.

In February 1864, Irsch was among 109 captives to tunnel out of Richmond’s infamous Libby Prison. Some reached safety, but Irsch was recaptured. He was finally exchanged in March 1865 and returned to duty with the 45th.

Irsch received the Medal of Honor for his Gettysburg heroism in 1892. Unfortunately, his postwar years were plagued with ill health and failed business ventures. He died in poverty in Tampa, Fla., in 1906.

–Stuart R. Dempsey Guide #208, licensed in 2004

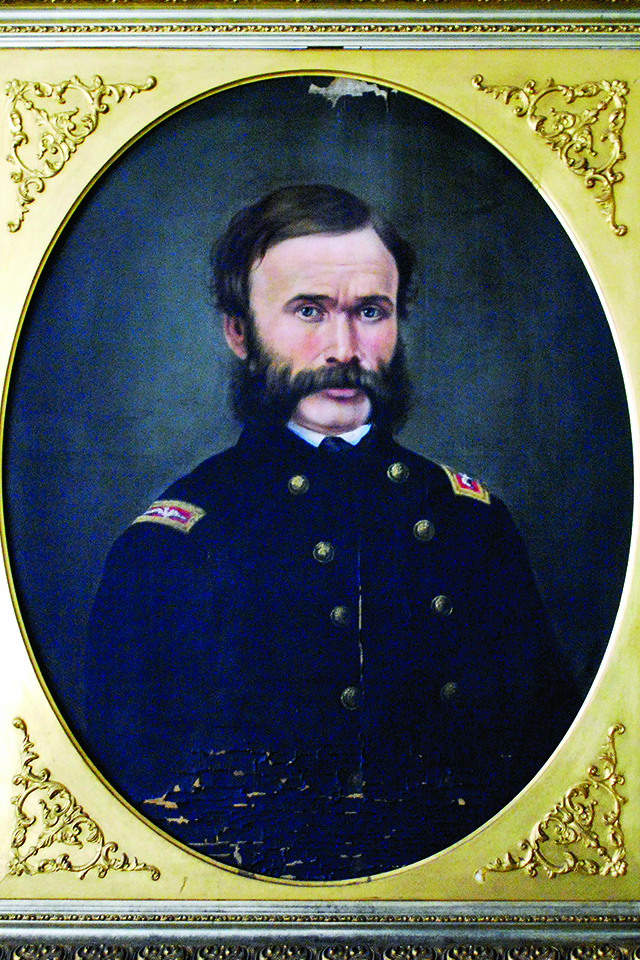

Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery

1st Volunteer Brigade, Artillery Reserve

Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery was a former sea captain from Maine turned Federal artillerist. By mid-1863, his star was rising as a tough but trusted officer. At about 3:30 p.m. on July 2, he was ordered to support Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ 3rd Corps near the Peach Orchard. He rushed forward with his two most trusted batteries and deployed them just east of the orchard amid enfilading

Confederate artillery fire. A brigade of South Carolinians soon tested McGilvery’s artillerymen, with McGilvery claiming he was “sure that several hundred were put hors de combat in a short space of time.” This, however, was not just a boast. “We were truly ‘in a box,” wrote Private John Coxe, “liable to be captured or annihilated at any moment.”

Even as the Confederates overran the Peach Orchard, McGilvery organized a retreat by battery, knowing he undoubtedly would be trading his own men’s lives for precious time. The reciprocal trust between McGilvery and his subordinates was evident in their sacrifice that evening. McGilvery formed a new patchwork line of 13 guns along Cemetery Ridge, which quickly wreaked point-blank havoc on the Rebels and helped repulse the attack.

On July 3, McGilvery commanded 39 pieces of artillery along his line of the previous evening spanning Cemetery Ridge, and he was again instrumental—this time in repulsing Pickett’s Charge. McGilvery’s fighting career did not begin or end with Gettysburg, but performances like his provided the Union Army with its first major victory against Robert E. Lee. Later in the war, as chief of artillery for the 10th Corps, McGilvery was slightly wounded in the finger. Since he was not healing properly, surgeons decided to amputate the finger and the 40-year old McGilvery died of a chloroform overdose during the procedure on September 2, 1864.

–Britt Isenberg Guide #20, licensed in 2014

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Czar Merwin

27th Connecticut Infantry

Much of the traditional focus and interest surrounding Gettysburg is on the upper echelons of the armies—the general officers. But

My poor regiment is suffering fearfully.”(The Twenty-Seventh, a Regimental History)

lower-ranking officers in both armies also played critical roles in the three-day battle and should not be overlooked. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Czar Merwin is one of those unsung heroes. Merwin was a 23-year-old citizen officer who did not attend the U.S. Military Academy at

West Point; instead, he represented a contingent of young men in volunteer regiments who rose in the ranks through merit and personal reputation. Gettysburg was unfortunately Merwin’s final battle. He was killed in action leading the 27th Connecticut Infantry, a hard-luck nine-month outfit, into the fierce Wheatfield fighting the afternoon of July 2. The 27th was part of Colonel John R. Brooke’s 4th Brigade, in the 1st Division of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s 2nd Corps.

Today, no grand statue marks where Merwin fell, only a tiny, rather beat-up marker along the Wheatfield Road, often obscured by tall grass. Merwin was never recognized with a Medal of Honor. His role in the battle probably had little direct effect on the outcome—his troops were driven back and the Wheatfield fighting produced a stalemate.

There is a reason that Merwin and countless young officers like him deserve more attention for their efforts. He is an unsung hero not for changing the course of the Battle of Gettysburg, but because of his selfless service, the respect he earned from his men, and his exemplary conduct as a combat leader.

–David Weaver Guide #37, licensed in 1986

Captain Edwin William Miller

Company H, 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry

In the late afternoon of July 2, 1863, Captain Edwin William Miller and the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry clashed with Brig. Gen.

James A. Walker’s famed Stonewall Brigade on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge, east of Gettysburg. The brisk skirmish had important repercussions on the battle’s outcome. For the beleaguered Union defenders on Culp’s Hill that day, the absence of Walker’s 1,300 or so veterans during critical fighting helped keep the summit in Federal hands.

Miller and his troopers would have another memorable engagement the following day. Part of the Union cavalry screen east of Gettysburg, Miller commanded a squadron of four companies concealed in a patch of woods along the Low Dutch Road. By early afternoon, Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart had arrayed four cavalry brigades to their north.

In a series of chess-like moves, each side’s horsemen sought an edge. Dismounted cavalry advanced, retreated, reinforced, and retired. Stuart then launched a mounted attack, only to be blunted by a Union counterattack. Sensing a stalemate, Stuart finally ordered a coup de main—a mounted charge of his best brigades. The Federals launched another desperate counterattack. Southern troopers soon appeared before Miller’s position. Success or failure hung in the balance.

The captain turned and asked his lieutenants, “I have been ordered to hold this position, but if you will back me, in case I am court-martialed for disobedience, I will order a charge!” All agreed. Miller’s men fired a volley, charged, and crashed into the Confederate column’s “rear flank.” In the confusion, Confederates looked over their shoulders to see Union cavalry threatening their escape route to safety. The column disintegrated. The Army of the Potomac’s flank and rear had been secured.

In July 1897, Miller was presented the Medal of Honor. He is one of two Medal of Honor recipients buried alongside fellow unsung heroes in Gettysburg’s National Military Cemetery.

–Douglas Douds Guide #46, licensed in 2014

Corporal Francis A. Wallar

6th Wisconsin Infantry

Late in the morning of July 1, 1863, the 6th Wisconsin Infantry—one of five regiments in Union Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith’s 1st

Brigade in the 1st Corps’ 1st Division—was ordered to charge a Confederate position north of the Chambersburg Pike, west of Gettysburg. Within the ranks of the regiment’s Company I was a 22-year-old corporal, Francis Asbury Wallar, who had been born in Ohio but moved with his family to Wisconsin in the early 1840s. Standing 5-foot-8½-inches tall, Frank Wallar sported a light complexion, sandy hair, and blue eyes. After this day, he would become known as “brave a soldier as ever fought in the ranks.”

During the charge, the 6th Wisconsin, commanded by Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes, came under severe musket fire on its front. Dawes’ men quickly scaled two fence lines straddling the pike and charged across an open field toward awaiting Confederates, who had taken position within an unfinished railroad cut.

As the Wisconsin soldiers approached the cut, a Confederate color-bearer defiantly waved his flag in their direction, spurring the Badger State boys to make a mad dash for the flag. The color-bearer, Corporal W.B. Murphy of the 2nd Mississippi in Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Division of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Corps, later said that the Federals “kept rushing for my flag and there were over a dozen shot down like sheep in the mad rush for the colors.”

Murphy admitted, however, that “a large burly man made a mad rush for me and the flag. As I tore the flag from the staff he took hold of me and the colors.” That soldier was Corporal Wallar.

“I did take the flag out of the color bearer’s hands,” Wallar later revealed. “I thought about moving to the rear, but then I thought I would stay, and I threw it down and loaded and fired twice on it.” Wallar and the 6th had captured 230 Confederates, and Waller received the Medal of Honor in December 1864.

–Larry Korczyk Guide #254, licensed in 2012

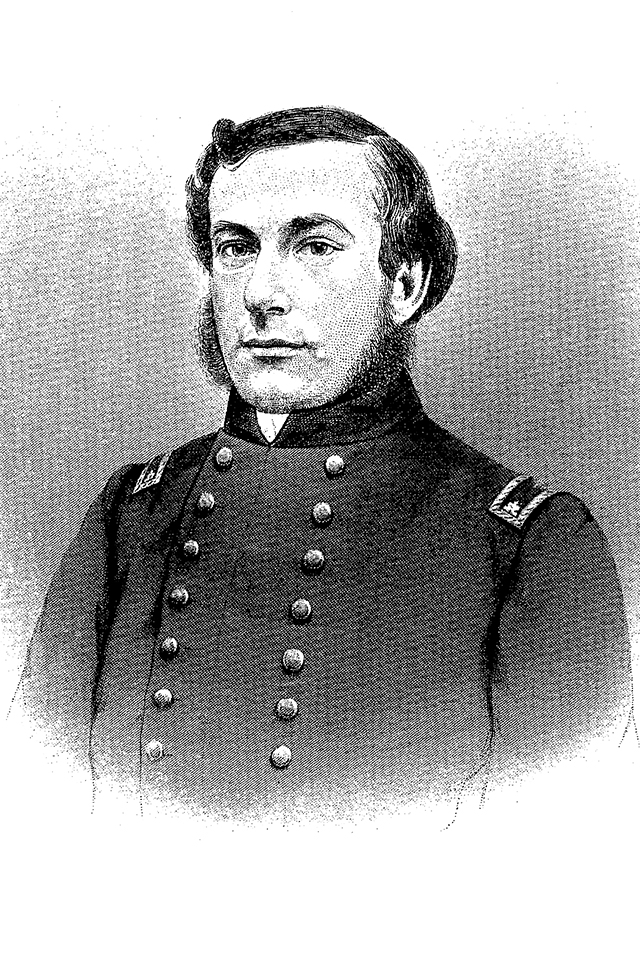

Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson

Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery

War correspondent Samuel Wilkeson’s grief at the loss of his 19-year-old son Bayard pours out in the opening paragraph of his article in the July 6, 1863, edition of The New York Times: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a

central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest—the dead body of an oldest born, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay?”

Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson commanded Battery G, 4th U.S. Artillery, which on the afternoon of July 1 was aligned alongside Lt. Col. Douglas Fowler’s 17th Connecticut in an area now known as Barlow’s Knoll. Confederate shells soon rained down on their position. To steady his men, Fowler encouraged them to “dodge the big ones, boys!” Wilkeson, meanwhile, remained on his horse in full view as he gave his cannoneers orders. Before long, a shell fragment tore off most of Wilkeson’s leg and killed his horse.

Using his sash as a tourniquet, Wilkeson remarkably began amputating his own leg with a pocket knife and, according to an eyewitness, continued to shout out orders until unable to continue. Four of Wilkeson’s men carried him to a local almshouse being used as a field hospital, but once there, the lieutenant ordered them back to the front.

When Wilkeson was handed a canteen, a wounded soldier near him implored, “For God’s sake, give me some.” In true form, Wilkeson handed the man the vessel before even taking a sip.

The next day, Samuel Wilkeson came to the almshouse to learn his son had died from his horrific wound. Through his grief, he was able to write his New York Times article, ending with: “Oh, you dead, who at Gettysburgh [sic] have baptized with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied!” Samuel’s words may well have inspired President Abraham Lincoln, who used this sentiment of a second birth of freedom in his famous Gettysburg Address in November 1863.

–Chris Army Guide #171, licensed in 2015

Colonel George l. Willard

3rd Brigade, 3rd Division, 2nd Corps

Most students of Gettysburg are familiar with Confederate Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s devastating Peach Orchard assault during the afternoon of July 2, when his Mississippi brigade smashed through the Union salient along the Emmitsburg Road and rolled toward

Cemetery Ridge. Less heralded, however, is the story of the Northern commander who helped stop Barksdale.

Colonel George L. Willard was a 35-year-old officer with considerable military experience. Although he did not attend West Point, he served with distinction in the Mexican War and held a commission in the U.S. Army when the Civil War broke out. In August 1862, Willard became colonel of the 125th New York. His regiment was attached to a brigade of other New York units—the 39th, 111th, and 126th—that only weeks later was captured humiliatingly at Harpers Ferry, Va. The regiments were soon paroled, some of the men earning the derisive nickname “Harpers Ferry Cowards” within the Army of the Potomac.

At Gettysburg, Willard served in Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays’ 3rd Division in Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s 2nd Corps. Only days before the battle, Willard received command of the entire 3rd Brigade. During the fading twilight of July 2, Barksdale’s Mississippians charged toward a gap in the Army of the Potomac’s Cemetery Ridge defenses. With the war cry of “Remember Harpers Ferry!” to motivate them, Willard’s men fixed bayonets and launched a counterattack

Willard’s charge forced the Mississippians back, and Barksdale fell mortally wounded. Unfortunately, Willard had little time to savor his success. As he returned to Cemetery Ridge, he was struck in the head by an enemy shell and killed instantly. In 1888, a small memorial was erected to commemorate where he fell. It might be one of the least visited monuments on the battlefield.

George Willard’s sacrifice that day is too often forgotten and overshadowed by the opponent he stopped from reaching Cemetery Ridge, but he is undeniably an unsung hero of the battle.

–James Hessler Guide #196, licensed in 2003

Lieutenant Colonel

Elijah V. White

35th battalion, Virginia cavalry

The Gettysburg heroes shrouded by history’s shadows who we feature in this issue each had his moment of glory during the three-day battle itself. Confederate Lt. Col. Elijah V. White, on the other hand, pulled off his memorable feats over the entire Gettysburg Campaign, beginning with the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, and ending when the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River

back into Virginia on July 14.

At Brandy Station, White and his command—the 35th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, in Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones’ Brigade—had a prominent role in preventing what at first promised to be a stunning Union victory but ended instead a blood-soaked draw. Caught by surprise, Jones’ troopers absorbed the initial Federal thrust that morning before recovering. A wild charge by White’s battalion cut short one Union onslaught and prevented a vulnerable unit of horse artillery from getting overrun. Later, the 35th temporarily captured a Union battery.

Brandy Station laid the groundwork for Gettysburg. Had the Federals prevailed, a Confederate excursion into Pennsylvania may well have been postponed or canceled outright. The near-loss had greatly embarrassed Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. On June 25, he embarked on what most experts consider an ill-advised eight-day raid through Northern Virginia and Maryland, leaving Robert E. Lee’s army in the blind during its push across the Mason-Dixon Line. After Brandy Station, the 35th had been dispatched to Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Second Corps and ended up as one of the few, if not only, of Lee’s cavalry units to sustain regular contact with the main army until Stuart reappeared on July 2.

On June 17, at Point of Rocks, Md., the 35th overran Captain Samuel C. Means’ Loudoun Rangers and captured 18 rail cars and equipment. Then, on the 26th, White’s men pummeled a militia guard at Marsh Creek before pursuing the awed soldiers into Gettysburg yelling “like demons” and wildly firing their pistols—the first Rebels to enter the town. Many of the militiamen simply dropped their weapons and asked for mercy. The next day, White led a raid to nearby Hanover Junction to destroy railroad bridges and cut telegraph lines. He also famously told the locals that, though his men wore suits of gray, as “gentlemen” fighting for a noble cause they would harm no one. On June 28, White led a push by John Gordon’s Brigade to destroy other railroad bridges as well as a covered span over the Susquehanna River at Wrightsville, Pa. By the time the 35th arrived, Union soldiers had already set fire to that bridge, so the regiment retired to York for a brief respite. During the battle, White’s men saw limited action, but on July 5 they were chosen to help protect the rear of

Lee’s retreating army. They had been the first to reach Gettysburg 10 days earlier; now they were in the last group to leave.

–Chris Howland, Editor, America’s Civil War