A volunteer battery’s resolve on July 1, 1863, merits more attention. It helped secure the Union victory

Alonzo Cushing. Freeman McGilvery. John Bigelow. Greenleaf T. Stevens. Their names are among those enshrined in the annals of the Battle of Gettysburg, as are the sites on the battlefield where these Union artillery commanders made history. Another Federal commander belongs on this list, however: Captain Lewis Heckman of Battery K, 1st Ohio Volunteer Light Artillery. What Heckman and his gunners accomplished on July 1, 1863, had a significant impact on Gettysburg’s outcome, yet more often than not their story gets overlooked in accounts of the epic battle.

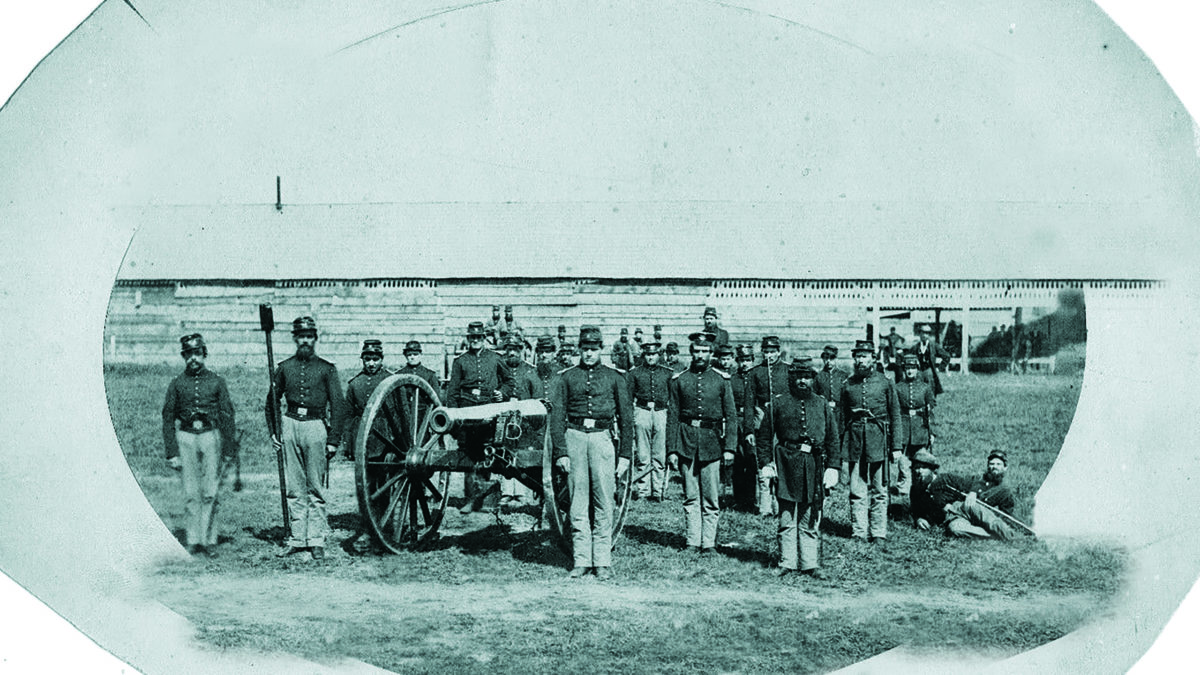

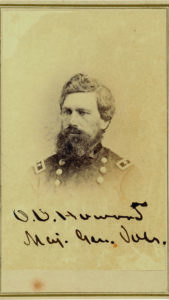

On July 1, the battle’s opening day, the 1st Ohio Light arrived on Cemetery Hill about 10 a.m. along with the rest of Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard’s 11th Corps. Howard’s infantry and two batteries—Captain Hubert Dilger’s Battery I of the 1st OVLA and Captain William Wheeler’s 13th Battery, New York Light Artillery—quickly advanced in support of the embattled 1st Corps north of Gettysburg. Heckman’s battery was kept back in reserve.

The 11th Corps established a line to the right of the 1st Corps, running from about the Mummasburg Road to the Harrisburg Road, but soon came under fire from Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Corps on Oak Hill. The six guns of Dilger’s battery and the four of Wheeler’s joined forces to counter Ewell’s artillery advantage, which included four 3-inch rifles and four 12-pounder Napoleons in Captain Richard C.M. Page’s and Captain William J. Reese’s batteries, part of Carter’s Artillery Battalion. Dilger and Wheeler had some success but were eventually overwhelmed, taking heavy casualties, and were left with little choice but to retreat hastily through town.

To counter the onslaught of Ewell’s galvanized Confederates, Heckman’s gunners were sent to a position on the Pennsylvania College campus (today’s Gettysburg College) at the intersection of Carlisle Street and what is now Lincoln Avenue, near modern-day Huber Hall. With 118 men and four cannons, Battery K would make a determined stand, firing an estimated 113 rounds (both shell and canister) in about 30 minutes—a rate of nearly four rounds per minute.

To counter the onslaught of Ewell’s galvanized Confederates, Heckman’s gunners were sent to a position on the Pennsylvania College campus (today’s Gettysburg College) at the intersection of Carlisle Street and what is now Lincoln Avenue, near modern-day Huber Hall. With 118 men and four cannons, Battery K would make a determined stand, firing an estimated 113 rounds (both shell and canister) in about 30 minutes—a rate of nearly four rounds per minute.

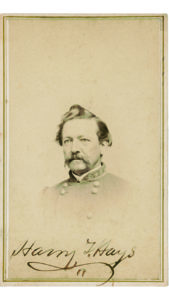

Inevitably, the Confederate rush of Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays’ “Louisiana Tigers” was too much for Battery K. Heckman managed to get two of his Napoleon 12-pounders out of the scrape but lost the other two.

The brief stand, though, helped soldiers of the beleaguered 11th Corps escape to Cemetery Hill, where they re-formed and were able to continue fighting. That would prove essential to the battle’s outcome two days later; without Heckman’s heroics, many more Federals would have been captured that first day with possibly serious consequences for the Union defense.

Battery K’s stunned survivors made it safely to Cemetery Hill, but they were in no shape to stay in action for the remainder of the battle. Major Thomas W. Osborn, the grateful commander of the 11th Corps’ Artillery Brigade, made sure to give Heckman and his battery due credit in his after-action report.

On July 13, 1863, a member of the battery, 20-year-old Sergeant Cecil C. Reed, wrote a letter about the engagement to the Morning Leader, a newspaper in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. The letter, printed in the paper’s July 24, 1863, edition, provided an excellent description of the battle’s terrible carnage. [The letter is reprinted here in its entirety with paragraph breaks added for readability.]

Headquarters of Battery K, O.V.A.,

Hagerstown, Md.,

July 13, 1863

Supposing that our many kind friends of Cleveland would like to know something of our movements since we left Fredericksburg [after the Battle of Chancellorsville], and the part we took in the great and glorious battle of Gettysburg, and I being at leisure I will give you a short sketch of our travels.—We left Fredericksburg on the 12th day of June for parts unknown, and after a long and severe march of nineteen days, on the last day of June arrived at Emmittsburg, a small town in Maryland near the foot of South Mountain, eight miles from Gettysburg. Then came the report along the line that our advance had overtaken the invaders, and there would surely be an engagement on the morrow. We soon received orders to make ourselves comfortable for the night, and you may be rest assured that it was not long until the boys were snugly ensconced—some under rail piles, some under the bushes and some under tents, with nothing to disturb their peaceful repose but some of the many pleasant dreams that never fail to visit the soldier’s couch.

Wednesday morning came, the first day of July, with rather an unpleasant rain, but we found it did not interfere with our marching. At one o’clock the order came for our battery to go to the front as soon as possible; then we had to double-quick it for three miles over the worst roads I have ever seen. We arrived on the field in due time, and it was not long until we were assigned a position by General Howard, in a field a little to the north and east of Gettysburg. We had hardly got our guns in position before the order came from the Captain to commence firing, for there was a brigade of rebels advancing to take us without any ceremony. No sooner said than done, we commenced giving them our best wishes in the shape of shell and canister, which mowed them down like wheat. But on they came, closing up their ranks wherever they were torn asunder by our shots, and they were not idle all the time; they were pouring in their volleys with telling effect. Our men were falling fast and they were coming so close that some of their skirmishers were literally blown to pieces from the muzzles of our guns.

We found it would not be very healthy for us to remain here, and we commenced making preparations for a retrograde movement; but when we came to move off the battery we found that one section had lost nearly all their horses, so we had to abandon it, not however until the guns were well spiked and rendered unserviceable to the enemy. We finally came off with two guns and all our [other] horses. Had it not been for Captain Heckman and his long experience as an artilleryman and an officer I am afraid we might have lost some of the latter, but he had them far enough in the rear and so they had time enough to get out. He said he would rather give the rebels all his guns than to give them his ammunition at the present time.

I think there was quite an oversight in not sending us a support; if we had had one regiment there I think we could have gotten all our guns off. But we had to support ourselves the best we could. The boys used their revolvers with telling effect on the rebels. All of our officers’ horses were shot from under them. Captain Heckman ran a very narrow escape; he had just dismounted when his favorite horse fell, pierced by two balls, but it was not long until he had the saddle off and was again mounted on a fresh horse. After he had gotten the battery off he rode back through the fire of the enemy to see if any of the boys were left on the field.

We cannot compliment our Captain too highly for the interest he took in our welfare, and the daring deeds he performed that day will be long to be remembered by us. The boys all stood to their post like brave men, and not a man left his post until he was ordered to do so. We were under fire about one half hour. It was the warmest we ever experienced. The rebels fought desperately, and seemed very well pleased when they closed around our guns. Lieutenant [Columbus] Rodamour had his horse shot; also, Lieutenant Schilly [sic]. Major Osburne [sic], chief of artillery, complimented us very highly, and wondered that we got off so well.

So ended our first and last day’s fight at the battle of Gettysburg. On the morning of the 3d inst., we were ordered to the rear as a disabled battery, but this was too good a thing for us, so they gave us another gun and sent us to the front. We are now the first battery in position at Hagerstown, and we expect to have something to do in the coming battle. The following is a list of the casualties:

Private Lewis Opert, Cleveland, Ohio. Killed.

Private Charles [Carl August] Ziesche,

Cincinnati, Ohio. Killed.

Lieutenant Charles M. Schilly [Schiely],118

Cleveland, Ohio. Wounded in left shoulder.

Private John McCullough, Washington County. Wounded.

Private Conrad Felton, Washington County. Wounded.

Private Timothy Gorman, Cleveland, Ohio. Wounded.

Private Jacob Smith [Schmidt], Cleveland, Ohio. Left on

the field.

Private Jacob Myher, Cincinnati, Ohio. Right cheek.

Private John Goodrich, Washington County. Leg.

Private William Cobbledick, Cleveland, Ohio, Hand.

Corporal Albert M. Cross, Belmont, Ohio. Taken prisoner.

Private William George, Cleveland, Ohio. Missing.

Corporal John Mowery, Virginia. Stunned.

Corporal Isaac Johnson, Virginia. Leg amputated.

It is reported this morning that the rebels have abandoned their works. You will hear from us after the fight. Yours, Cecil C. Reed.

In his official report, Major Samuel McDowell Tate, commander of the 6th North Carolina Infantry in Colonel Isaac Avery’s Brigade, stated that his men “captured a battery near the fence.” Tate’s “battery” was actually the two guns of Heckman’s battery Sergeant Reed had said were left behind “well spiked and rendered unserviceable.”

Following the battle, and refurbished with new guns, Battery K continued its service with the Army of the Potomac and then in the Western Theater. It saw action at the Chattanooga Campaign battles of Wauhatchie, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge in 1863. The Ohio boys finally mustered out and came home in July  1865.

1865.

The German-born Heckman, an antebellum confectioner and married father of four, survived the war, as did Columbus Rodamour and Cecil Reed. Heckman died in Rocky River, Ohio, on August 4, 1872. Rodamour enlisted in the Regular Army in November 1865 and was serving at Fort Reno, Okla., when he died from ascites (a fluid buildup in the abdominal cavity) on September 6, 1876. He was just 38. Reed, who had moved to California in 1867 and found work in the mining industry, died on June 30, 1923, in Berkeley, Calif. He filed for a disability pension with the federal government in July 1902, and it was granted; unfortunately, his file has been lost at the National Archives.

An impressive monument to Battery K, 1st Ohio Volunteer Light Artillery, stands on the Gettysburg College campus, at the southwest corner of Lincoln Avenue and Carlisle Street. It was erected on September 14, 1887, the ceremony attended by the unit’s survivors, along with other Ohio veterans being recognized at the battlefield that day. Because of its location, however, the memorial isn’t on most battlefield tours. Instead, it is usually left in the shadows—like the unit it honors.

_____

Organized Iron

» Captain Lewis Heckman’s battery was armed with bronze 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannons, formally called Light 12-Pounder Guns, Model 1857. Each cannon was towed by a limber, on which sat an ammunition chest that organized the gun’s ordnance. The standard load for each chest was 32 rounds, and the 1859 manual Instructions for Field Artillery, written by U.S. Army officers William

French, William Barry, and Henry Hunt, explicitly described what types of rounds were to be carried in the chest and how they were to be organized. Some battery commanders precisely described the specific amounts and types of ammunition they fired in their after-action reports, but Heckman did not do so in his short July 28, 1863, report of the Battle of Gettysburg. He simply stated that his four Napoleons “expended 113 rounds of ammunition, mostly canister,” in his battery’s desperate effort to hold off surging Confederate attacks. That means his men exhausted nearly all the rounds they had in their ammunition chests and likely had to have canister rounds brought up from the caissons, basically wagons with more ammunition chests, that were kept in the rear. The image at left illustrates how ammunition was stored in a chest based on information in Instructions for Field Artillery.

1. Spark Deflector The top of the ammunition chest’s lid was covered in sheet copper to prevent sparks from igniting the rounds. During action, two men from the gun crew, numbered 6 and 7, were posted at the chest. Number 7 opened and closed the lid, while Number 6 selected rounds according to the Gunner’s directions, and handed them to a man designated Number 5 to run them up to the cannon.

1. Spark Deflector The top of the ammunition chest’s lid was covered in sheet copper to prevent sparks from igniting the rounds. During action, two men from the gun crew, numbered 6 and 7, were posted at the chest. Number 7 opened and closed the lid, while Number 6 selected rounds according to the Gunner’s directions, and handed them to a man designated Number 5 to run them up to the cannon.

2. User’s Guide Every chest had a “Table of Fire” pasted under the lid, which contained instructions for cutting fuzes for the correct range and also how to care for the chest. It admonished, “beware of loose tacks, nails, bolts, or scraps” that could create sparks. The quoted material below is from the Table of Fire.

3. Storage Unit Each chest also had an implement tray, seen here with its bottom removed for display purposes, that held 48 friction primers and various other accoutrements and implements needed by the crew. The tray could be lifted out and moved from side to side to access rounds underneath.

4. Shotgun Blasts The far-right slot in the chest held four canister rounds effective up to 500 yards; here they are hidden under packs of friction primers. Double charges of canister, tin cans filled with iron balls to devastate infantry, could be fired if the powder bag was detached from the second round. With only four rounds of canister, Heckman would have certainly needed more brought up from the rear.

5. Deadly Shrapnel These divisions contained 12 case shots, explosive rounds filled with musket balls to increase potency, and to be used against troops from 500 to 1,500 yards.

6. Wrecking Balls These slots held 12 solid shot, used to fire “at masses of troops…from 600 up to 2,000 yards.” All the projectiles in the chest were “fixed,” meaning they were already attached to bags containing 2 to 2.5 pounds of gunpowder.

7. Big Bangs Four explosive shells stored in this division were considered better at producing a “moral, rather than a physical effect.” Their greatest range was 1,500 yards.–D.B.S.

Jeffrey Stocker, a retired attorney, is the author of three books on the Civil War, including “We Fought Desperate”: A History of the 153rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He makes a point to stop by the isolated Battery K monument whenever he has a chance to visit Gettysburg.

This story appeared in the July 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.