For 94 of his 100 days in Vietnam (May 10 to Aug. 11, 1972), Joe Tallon, who piloted a U.S. Army OV-1 Mohawk observation plane, spent much of his time trying to get a dysfunctional motor pool in working order while also flying dangerous reconnaissance missions over North Vietnam. The American presence in South Vietnam was dwindling. Tallon’s unit, the 131st Military Intelligence Company at Marble Mountain in Da Nang, was chronically short of materiel and personnel.

Tallon’s life changed forever on his 95th day in-country, Aug. 12, 1972—the day the last U.S. ground combat unit in Vietnam was deactivated at Da Nang. Minutes after Tallon took off on his 66th mission, the Mohawk’s No. 2 engine was hit by groundfire and burst into flames.

Tallon tried to control the plane, but couldn’t. As the aircraft rapidly descended, he ordered his technical observer, Spec. 5 Daniel Richards (who had reported to the unit that very day), to eject. Ten seconds later Tallon pulled his ejection handle. The two men were just 100 feet off the ground. Tallon barely survived, suffering extensive, severe burns on his arms and legs and fractured vertebrae. Richards did not make it.

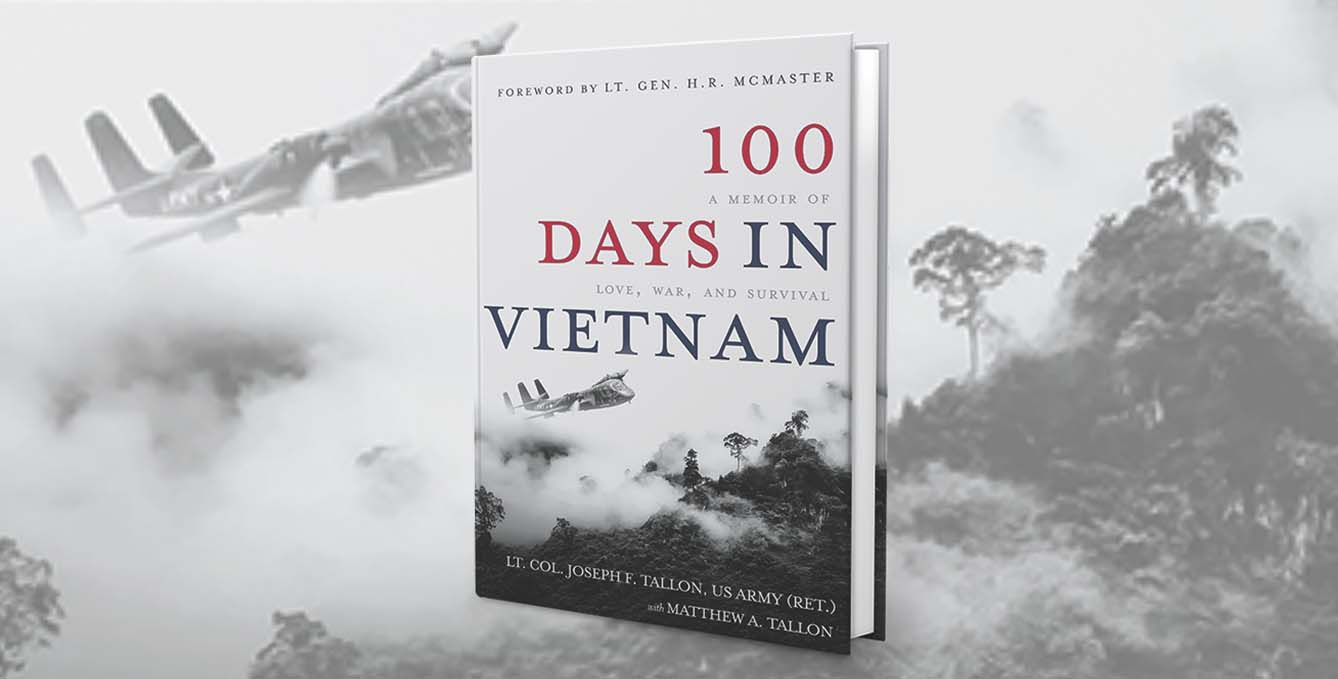

Tallon tells his Vietnam War story in a straightforward memoir, 100 Days in Vietnam, focusing mainly on his frustrations with deteriorating morale and equipment shortages and the many months he spent in Army hospitals recovering from his wounds after he was shot down.

There also are lots of details about another unpleasant aspect of his military career—fighting with the Army for three years to stay on active duty after he recovered from his wounds. In 1975, Tallon reluctantly accepted a forced retirement, with “0 percent disability,” he says, and “no retirement stipend or compensation.”

Ironically, a year later the Army Intelligence School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, asked Tallon to teach a course to new intel officers. Even though the Army, as Tallon puts it, “booted me out,” he agreed to teach temporarily. He wound up staying in the Army Reserves until 1996, retiring as a lieutenant colonel.

In 2008, Tallon was finally awarded a Purple Heart, which he hadn’t received because his plane’s crash was officially characterized as a “non-hostile” accident. Tallon won that battle and then waged another years long one to get Richards the medal, presented to the soldier’s family in 2012.

Tallon peppers the pre-shootdown sections of the book with letters he wrote to his wife, Martha Anne, and those she wrote him, along with transcriptions of cassette tapes they exchanged. The letters contain many mundane details—on his part, mainly about the frustrations of his motor pool work and dealing with low morale and, on hers, about the day-to-day aspects of life back home. The correspondence also includes many words of love and devotion and discussions of the couple’s religious faith.

The memoir picks up steam with the vivid, sometimes searing, depictions of Tallon’s final flight, the immediate aftermath as he fought for his life, and the extreme physical pain and psychological despair he endured as Army doctors and nurses treated him.

The final section describes the hard work and perseverance that was necessary for Tallon—and his son Matthew—to convince the Pentagon bureaucracy that Richards should be awarded the Purple Heart, an upbeat ending to Tallon’s story.

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

This article appeared in the December 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.