For many former slaves, the battle for freedom did not end with Union victory in the Civil War

The 1863 Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately bring freedom to enslaved people. In her new book Embattled Freedom: Journeys Through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (UNC Press, 2018), Amy Murrell Taylor, an associate professor at the University of Kentucky, demonstrates how hard and in how many ways refugees from slavery had to fight to secure the freedom for which they yearned.

Your book’s title, Embattled Freedom, evokes the image of former slaves having to fight not only to obtain freedom, but to keep it. What do you mean by that?

A great misconception is that when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, suddenly the slaves were free. In fact, realizing the promise of the proclamation was contingent on two things. First, an enslaved person had to get themselves into a place—the Union lines—where freedom would be recognized. Second, the Union had to win the war. Refugees therefore had to fight for their freedom every day.

What happened when Union troops entered slave-holding Rebel territory?

President Lincoln initially did not want to interfere with slavery. What happened, however, was that the Union’s need to win the war—military necessity—dictated that he had to interfere. Enslaved people realized this: They knew that it was in their own interests—and the Union’s—if they left plantations and labored for the Federal Army instead of the Confederates. Major General Benjamin Butler at Virginia’s Fort Monroe was the first general to agree that their flight could undermine the Confederacy. Starting in May 1861, Butler allowed escapees to stay inside Union lines. He called them “contraband”—in other words, enemy property seized in a time of war. They would be protected from recapture, but were still considered property.

What did the former slaves want?

Besides food, shelter, and simply being protected from recapture, refugees wanted to begin the process of living as free people. They wanted work—and to be paid for it for the first time in their lives. They wanted to save money so they could be independent, and maybe buy property. They wanted education. They wanted to worship freely in their own churches.

What did the government do?

The Union Army put them to work digging trenches, building structures, helping in hospitals, or doing domestic tasks. Some were made guides or scouts because they knew the terrain. They often weren’t paid, especially in the beginning of the war when Union officials still considered refugees to be confiscated property. Many times their wages or food rations were stolen.

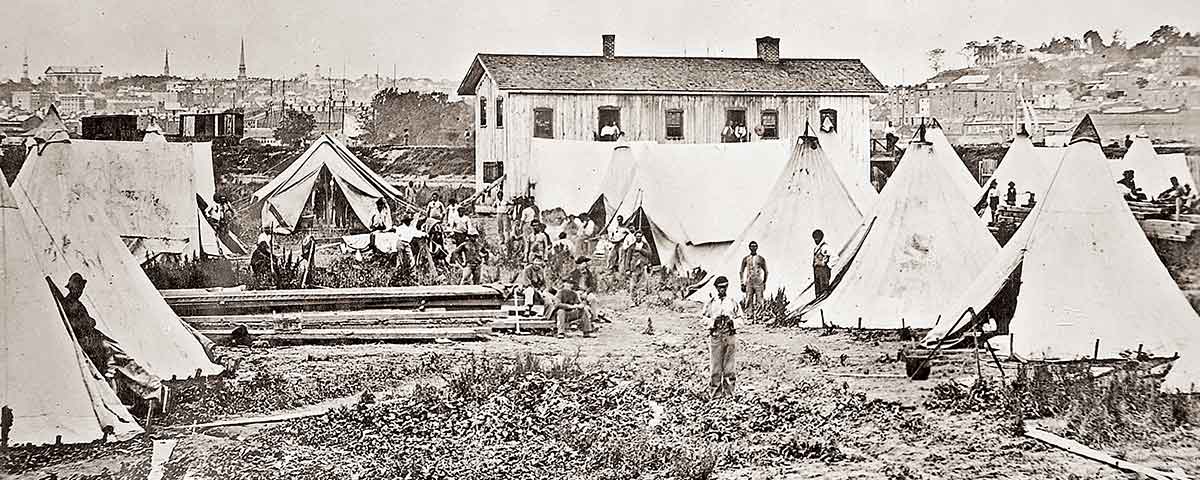

What were the camps like?

Most were about as deplorable as one might imagine. The refugees were issued tents—usually the most dilapidated—or building materials deemed unusable for soldiers’ barracks. They were often forced to build shelters in the lowest-lying areas of an encampment. No flooring material was provided and the tents were always at risk of flooding. They were crowded; illness and hunger ran rampant. Many refugees tried to take control of their own needs and not rely on the Army. Gardens were common, but the arrival of the enemy could force residents to abandon their plots.

Talk about the more “organized” camps.

In a few places more removed from active fighting, the camps were somewhat more permanent. In particular, Northern missionaries and aid workers designed some camps to look like a New England village with houses around a town square. The white benefactors believed that crowding brought with it a host of evils, including disease, crime, and disorder. They wanted the residents to disperse and live in small nuclear-family dwellings. To them, the father/provider mother/nurturer family structure groomed ex-slaves to be good citizens. Former slaves, however, lived through a time when fathers were sold away and parents and children separated at an owner’s whim. Many of them created families that were big, extended mutual aid networks not necessarily related by blood. They wanted to live with everybody they cared about, even if it meant crowding. This created tension with the Northern aid workers.

What was the greatest threat to the camps?

After Vicksburg was captured and Sherman’s army began moving east, fewer Union soldiers were in the Mississippi Valley to provide security to the hundreds of thousands of refugees living in camps along the river. Blacks also began enlisting in USCT regiments, which left women and children behind in disproportionate numbers in the camps—vulnerable to racial violence from Confederate guerrillas who attacked the camps repeatedly. Some freed people armed themselves and fought back.

Your book tells the story of slaves’ journeys to freedom specifically through the eyes of three families. Why did you choose to organize your book around these families, and how did you find the records upon which you base your story?

When I started, I wanted to know what it was like, on a day-to-day basis, to spend three or four years living in a refugee camp to become free. I figured this story would be best told by following the lived experiences of particular people over three to four years. Finding records was very difficult, because few people coming out of slavery wrote correspondence or firsthand narratives. I studied Union Army records, including provost marshal records and commanders’ order books, and correspondence between officers and Northern benevolent society workers. There were few words from refugees themselves, but I started seeing certain people’s names appearing in multiple records and realized I could still learn a lot by piecing together their movements and actions. Much remains unknown, however.

Talk about what happened as the war ended and white soldiers were demobilized.

We think of the war’s end as a victory over slavery, but I found it also was a time of loss for those trying to become free. As the Union Army contracted, it took away the physical protection, the employment, and the food rations that the refugees needed. The new president, Andrew Johnson, chose to return confiscated land to its Confederate owners. The camps were closed, the shelters and gardens destroyed, and the refugees forced to leave. This was devastating to the freed people, who lost their homes, their livelihoods, their schools, and their churches.

Were any of the subjects of your narrative ever truly free?

It’s important to note that the people I wrote about made some progress. When talking of Reconstruction, we often fall into the language of success or failure, and the truth for these families is somewhere in the middle. They started out after the war with virtually nothing, especially when the camps were destroyed. Yet in the three cases I wrote about, people did end up owning some land by the beginning of the 20th century. That’s significant because when you own your own land, you’re independent. There were still many obstacles, and freedom was not something that came to these families in a moment. They still would have to keep fighting for it in the years to come.