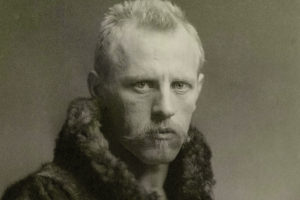

Fridtjof Nansen gained worldwide fame as a polar explorer. Then he took on a wartime refugee crisis.

WHEN THE PILGRIMS LANDED ON CAPE COD BAY IN WINTRY NOVEMBER 1620, they brought with them many essential items—food, guns, supplies to establish a new colony, members of both sexes—even the governing document that would become known as the Mayflower Compact.

One thing they did not think to bring with them, however, were passports.

Not that passports were unknown in 1620. In fact, the idea of a travel document that identifies the bearer and confers some degree of protection is almost as old as travel itself and examples of such documents appear as far back as the Old Testament. In Nehemiah 2:7–9, Nehemiah requests permission from his ruler, King Artaxerxes I of Persia, to travel to Judea. He is given a letter to the governors “beyond the river” requesting safe passage. The year is 450 bce.

By the 15th century both Kings Henry V of England and Louis XI of France had formulated documents to help their subjects, particularly royal couriers, prove who they were and obtain safe passage in their travels. The very word “passport” derives from the French passer, “to pass,” and porte, “gate,” as many such documents initially allowed a traveler to enter the gate of a walled or fortified city.

Over time the use of passports grew as central governments increasingly used them to control their subjects and keep out foreign bandits, vagrants, and other aliens deemed undesirable.

The explosive development of mass transportation (rail and steamship) in the latter half of the 19th century, and the accompanying liberalization of trade, appeared to signal the death of the passport system. The sheer speed and number of travelers overwhelmed the enforcement capacities of the state. As a result, passport laws fell into disuse or were abandoned altogether. Few people even bothered to have passports, and few governments required them.

World War I shot all that to bits.

The Great War, as it was then called, involved almost all the nations of Europe. With the onset of the conflict, governments emphasized border security—both to keep unwanted and potentially dangerous aliens out and to keep those with useful skills in. Designed as a temporary wartime measure, passport controls lived on after the war ended in 1918, as fears of foreign subversion, economic concerns, health issues (an influenza pandemic was underway), and just plain old xenophobia gained the upper hand.

Equally important, World War I, in the process of destroying empires, also spawned revolutions, the most cataclysmic and consequential being the Russian Revolution. Revolution’s evil twin—civil war—in turn spawned a new class of “stateless” refugees—those who were neither citizens in their adopted country nor welcome back in their country of origin.

In Russia’s case, this state of limbo was enshrined in law when the Soviet government effected the largest denationalization in history. On December 15, 1921, it defined “stateless refugees” as 1) those who had lived outside the country for five years who had not obtained new passports, 2) those who had left the country without permission after November 7, 1917 (the date of the Bolshevik Revolution), and 3) those who had fought against Soviet authority—so-called White Russians. The decree affected some 700,000 to 800,000 Russians living in Germany, Poland, France, Romania, and even Great Britain. (The fifth season of the hit British television series Downton Abbey nods to such displaced people in an episode featuring a disheveled and shabby Prince Igor Kuragin, who is discovered in a London soup kitchen by his former lover, the Dowager Countess of Grantham.) Hundreds of thousands of Armenians fleeing genocide in Turkey found themselves similarly stranded, in France and Syria.

Stateless people suffered under a triple impediment: First, as noncitizens in their host country, they were not entitled to any of the perquisites of the new postwar welfare state: education, unemployment benefits, and health care. Second, with no citizenship elsewhere, they could invoke no protection against the arbitrary actions of their host state. Under the law of nations, as then formulated, such people were entitled to “no protection whatsoever.” Third, lacking a valid passport, they had no guarantee of safe return to their host country or home country, and countries were reluctant to admit any alien who had no place to which to return.

Thus, a passport became a sine qua non of existence in the post–World War I landscape. As Hannah Arendt, the German-born philosopher and political theorist (and no stranger to the precarious life of a refugee), observed: “Once they [refugees] left their homeland they remained homeless, once they left their state they became stateless; once they had been deprived of their human rights they were rightless, the scum of the earth.” Stefan Zweig, an Austrian writer who fled to England following the Nazi takeover in Germany, succinctly summarized a lesson he had once heard from a Russian refugee: “Formerly man had only a body and soul. Now he needs a passport as well, for without it he will not be treated as a human being.”

The postwar refugee problem festered in Europe, ameliorated somewhat by the relief efforts of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the American Relief Administration (led by Herbert Hoover), and Quaker and Jewish groups. But late in 1920, as many as 200,000 Russians fled to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) in the wake of the final defeat of the White Russians. The problem now overwhelmed the capabilities of private charity or the ICRC to address.

At a conference called in February 1921, the ICRC approached the newly formed League of Nations and asked that it appoint a high commissioner for Russian refugees, with all necessary powers to tackle the problem.

Who could undertake such a formidable and thankless task? The ICRC already had a candidate in mind. The high commissioner, it said, “would do for the Russian refugees the kind of work Dr. Nansen had so successfully undertaken on behalf of prisoners of war.” In other words, if Fridtjof Nansen wanted the job, it was his for the taking.

Who was this Fridtjof Nansen?

In this day of hyperspecialization, it is almost impossible to envision the meteoric, and wide-ranging, career of Fridtjof Nansen. Born into a well-to-do Norwegian family in 1861, Nansen first pursued marine biology, contributing useful discoveries in the field of invertebrate neurology. To conduct his experiments, Nansen traveled with Norwegian seal ships plying the Arctic waters, and there the daring nature of polar exploration soon captured his imagination. As a young man he had always enjoyed challenging himself—living alone in the wild for weeks without equipment and with only “a crust of bread and fish which I broiled in the embers.”

At age 27 Nansen set out to cross the Greenland ice cap from coast to coast. All previous attempts to achieve this feat had met with failure, and so Nansen threw conventional wisdom to the winds. He deliberately assembled the smallest (and thus fastest) team feasible; planned to use skis to the greatest extent possible; and, most daring of all, chose to trek from the uninhabited east coast to the safe harbor awaiting on the west coast rather than pursue a round trip, as all of his predecessors had done. Once launched, the trek could have no Plan B, no escape, no rescue. Nansen once explained his rationale this way: “One loses no time in looking behind, when one should have quite enough to do in looking ahead—then there is no chance for you or your men but forward. You have to do or die.”

Successful in his bid, Nansen returned to Norway a national hero. The Greenland adventure only whetted his appetite for greater glory. The grand prizes in those days remained the poles—distant, forbidding, and dangerous for those foolish enough to make the attempt.

At 31 Nansen now set his sights on the North Pole. Again he defied conventional wisdom. Rather than avoid the polar ice, graveyard to many a ship, Nansen decided to use the ice to his benefit. He would build a ship (named, appropriately enough, Fram, or Forward) designed to sail directly into the arms of the ice on the eastern edge of the polar cap, but with a hull so rounded, the ice would be unable to gain any purchase on it and thus crush it. Once so captured, Nansen would rely on the westerly drift in polar current (which he theorized existed) to carry his ship up directly over the North Pole, with the crew safely and snugly ensconced inside.

The theory was correct, but Nansen soon realized that the arc of the drift would carry his ship close to, but below, the North Pole. Undaunted, he abandoned the Fram and, with one companion and 28 sled dogs, attempted to ski and sled the remaining distance to the pole. Leaving the ship forever meant that, even if successful in his quest, Nansen would need to return all the way back to civilization under his own power. Braving wind, snow, ice, and temperatures that hovered around –40 degrees Fahrenheit, Nansen pushed on. Dwindling food, slower than expected progress over the rough terrain, and the forbidding approach of the polar winter (and six months without sunlight) turned him back within 230 miles of his goal—a new record that stood for years. Nansen’s return trek has all the earmarks of the best adventure stories: insuperable odds, near-death experiences, incredible luck, indomitable will—and a happy ending.

Fridtjof Nansen was now an international celebrity. In 1905 he helped Norway achieve its independence from Sweden. He also persuaded Prince

Carl of Denmark to become king of the newly independent nation and served as Norway’s first ambassador to Great Britain. According to one historian, by 1918 he was “unquestionably the most towering personality of the post-war world.”

But Nansen had yet one more role to play—that of humanitarian.

Given Fridtjof Nansen’s larger-than-life reputation, in some ways it seems almost preordained that, when the fledgling League of Nations agreed to tackle its first major international crisis—the thousands of POWs scattered throughout Europe at the end of World War I, all without any means of repatriation—it would turn to him for help.

There was no plan to follow, no precedent, no staff. But through sheer doggedness, he secured the shipping and rolling stock he needed, as well as the cooperation of all the former belligerents. (Norway had remained neutral during the war.) In the end, he successfully repatriated almost a half million POWs. Little wonder that the ICRC saw Nansen as the logical candidate to address the refugee crisis. The League of Nations, acting on its request, appointed him high commissioner for Russian refugees on August 23, 1921, and he formally accepted the post on September 4.

Repatriating POWs who wanted to return to a home that wanted to receive them, however, was a far cry from helping refugees who often neither desired, nor were able, to return to their homes or to move anywhere else. As Nansen biographer Roland Huntford put it, “By most legal codes they simply did not exist.”

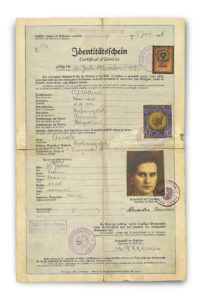

To address this issue, someone working with Nansen—some credit Philip Noel-Baker, later a Nobel Peace Prize laureate; others Edouard Frick of the ICRC—suggested a simple identity card, similar to a passport, that would be recognized by international agreement. Nansen adopted and promoted the idea. Early in July 1922 he convened an Intergovernmental Conference on Identity Certificates for Russian Refugees, which approved a model form of “Certificat d’Identité” (French then being the language of international diplomacy). The certificate almost immediately became known, and was commonly referred to, simply as the “Nansen passport.” By the end of that year 20 nations recognized it as a valid identity document. Eventually more than 50 countries would agree to issue and recognize the Nansen document, and in time the name “Nansen passport” would even become its official title as well.

Initially the Nansen passport provided few actual benefits. Issued by the country of residence on behalf of the High Commission, it served merely as an identity card. It did not grant the holder the privilege of residence or the right to seek employment.

Subsequent conferences, however, slowly accreted more and more benefits. Ultimately the Nansen passport would ensure the right of reentry to the issuing country—a crucial step in removing, once and for all, the single greatest impediment to crossing national borders.

The Nansen passport worked as well as it did because all parties involved wanted it to work. The formal, legal agreements adopted over time by league countries represent only half the story. The rest has to do with the moral authority the Nansen passport came to confer. In various capitals, holders of a Nansen passport could turn to representatives of the High Commission, who provided quasi-consular services on their behalf. When expulsion orders were issued or work permits denied, for example, representatives could and would take up the matter with the relevant national ministries.

The passport’s moral authority was further enhanced when Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1922. Indeed, by the time of Nansen’s death in 1930, refugees with a Nansen passport “enjoyed many of the same benefits as nationals.”

Initially issued only to Russian refugees, the program was subsequently extended to Armenians (in 1924) and Assyrian and Kurdish refugees (in 1926). The work of the High Commission was carried out following Nansen’s death by the Nansen International Office for Refugees within the League of Nations. In 1938, this organization, too, would earn the Nobel Peace Prize for its work.

SOME 450,000 NANSEN PASSPORTS WERE ISSUED BEFORE THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR II eclipsed the refugee problem. They enabled many Russian émigrés to travel as freely as any other citizen. Many, including such notables as writer Vladimir Nabokov (who mentions the Nansen passport several times in his fiction), pianist Sergey Rachmaninoff, and composer Igor Stravinsky used their Nansen passport to start a new life in America. Following the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, the family of Aristotle Onassis, the future shipping magnate, arranged for him to flee from Greece to Argentina using a Nansen passport.

For the first time, the status of the refugee was internationally recognized and addressed. While Nansen passports are no longer issued, they provided a template for documents subsequently issued by national and supranational entities, including the United Nations.

In 1938 Dorothy Thompson, who four years earlier had become the first American journalist to be expelled from Nazi Germany, published Refugees: Anarchy or Organization?, a pre-Holocaust plea for the world to find a place for the Jews of Europe. By then a new, and worse, refugee crisis was brewing in Europe. Unfortunately for Germany’s Jews, the old forms and conventions no longer worked. Since many Jews fled Germany with their passports intact, they did not technically qualify as “refugees.” Moreover, the League of Nations was (until late 1933, when Germany left the organization) leery of offending one of its most powerful members and thus ducked the issue it had so forcefully confronted in 1921.

With refugees once again in the headlines, both in the United States and abroad, Dorothy Thompson’s plea has as much resonance as it did in 1938. “What the whole refugee problem needs today, more than anything else, is another Nansen,” she wrote, “with his simple belief in human dignity, his enormous sense of personal honor and responsibility, and his confidence in the power of humanity to organize and mobilize to meet its emergencies.” MHQ

Timothy J. Boyce, a lawyer and writer who lives in Tryon, North Carolina, is the editor of From Day to Day: One Man’s Diary of Survival in Nazi Concentration Camps (Vanderbilt University Press, 2016).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: ‘You Have to Do or Die’