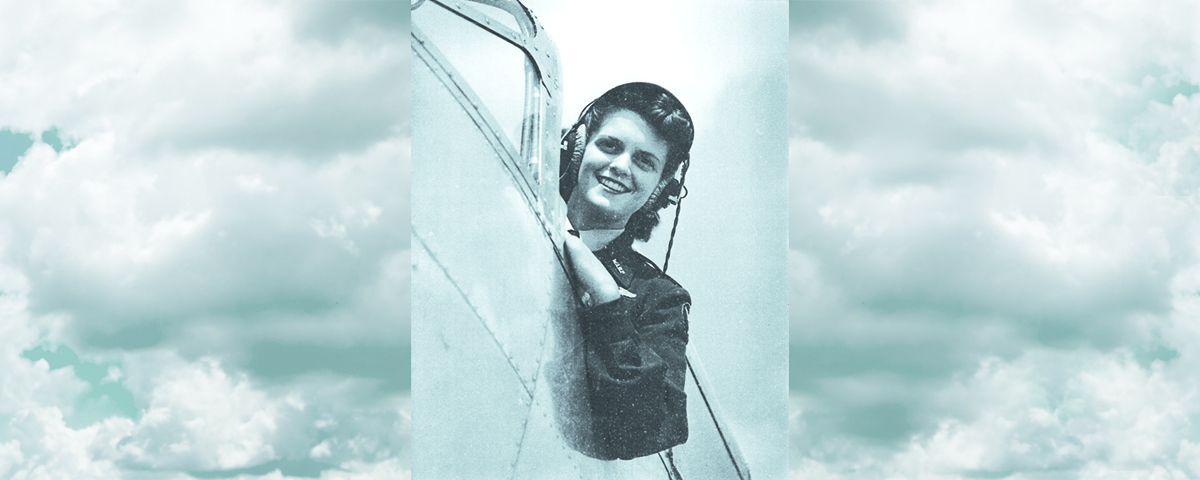

Little more than 1,000 of the more than 25,000 women who volunteered for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) organization during World War II made the cut. Jane Doyle was one of the lucky few. Almost all of those chosen were already qualified civilian pilots, and their mission was to operate U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) aircraft in noncombat roles, thus freeing male pilots for frontline duty.

Born in Grand Rapids, Mich., in 1921, Doyle had earned her pilot’s license while in college and entered the WASP program with more flying experience than many male cadets at the time. WASPs logged more than 60 million miles before the USAAF disbanded the program in December 1944. Despite having flown U.S. military aircraft during wartime, the female pilots were not granted veteran status until 1977. In 2009 Congress collectively awarded the WASPs a Congressional Gold Medal.

What drew you to flying?

When Charles Lindbergh came to Grand Rapids, my mother took me out to the airport to see him, and we saw the Spirit of St. Louis. I was 6 years old, but I remember it really well.

While in junior college I was taking an engineering drafting course. The instructor said they were going to start the Civilian Pilot Training Program, and they’d let one woman in for every 10 men. I thought that sounded interesting. I was the only girl in that engineering drawing class, so I sat back in the corner, but after class I went up to the instructor and said, “Can I apply for that?” He said, “Sure, but you have to take the physical.” He said, “You have to be 5 feet 4 inches.” I was 5 feet 2 inches—5 feet 2½ if I stretched. I thought, Well, I guess that takes care of that. However, later he said, “No, they changed it for women, it’s 5 feet 2½ inches.” So I took the physical, passed and got accepted that summer.

You were 18 at the time?

Yes. I got my private license then. They had started the Civilian Pilot Training Program at the end of 1938, because Germany was building up its air force, and we only had a few planes.

I got into the Civil Air Patrol so I could keep up my license. In 1942 the famous female aviator Jacqueline Cochran had gone through the records and found every woman pilot in the United States. I got a telegram asking if I was interested in joining the WASP program, and I replied that I was. On November 1 I got a notice that I’d been accepted into the class of 1943.

Was there any pushback from male pilots?

At that time there wasn’t, but it started to develop when pilots were coming back from overseas, and they wanted the flying jobs. General [Henry H.] Arnold [USAAF commander] wanted us to be part of the military, and Cochran did too, but if we weren’t accepted as members of the military, they would have to disband the program. Congress rejected the bill twice. They were getting too much pressure from male pilots, so the program was disbanded in 1944.

Did you want to fly in combat?

Not really—I just liked flying. Though I felt, If men can do it, women can do it, too, I had reservations about women flying in combat. I think it’s harder for a family to lose a mother than a father, really. We made a big advancement, but sometimes things go too far.

‘I had reservations about women flying in combat. I think it’s harder for a family to lose a mother than a father’

Did you have a favorite aircraft?

Yes, the AT-6. That was a nice one to fly—I loved that little plane. (I had flown a little Piper Cub before that.) I got down in that cockpit with the helmet and the goggles, and I said, “Oh, boy! This is it.”

What was your most challenging flight?

There was one particular cross-country trip—a 2,000-mile journey from Texas to Oklahoma to Louisiana to Arkansas and then all the way over to Alabama and then back. At that time there was no radio communication for navigation. They had beams across the country, and you flew on one side or other of the beam and got a Morse code signal. If you were right on course, you got a solid signal. That was our navigation.

How dangerous was it for WASPs?

Well, 38 got killed during their service. Two weeks before graduation from WASP training one girl was coming in for a landing, and one of the new students who had just arrived came in from the opposite direction—which she shouldn’t have—and they had a midair collision that killed both of them. We weren’t authorized funeral expenses. If someone was killed, we took up a collection, then someone went home with the body. But those who died weren’t allowed a military funeral.

Why did you decide to leave the program?

I was sent to a base for twin-engine training, because I was supposed to fly B-26 Marauder medium bombers in the target-towing role. I got the notice the program was being disbanded, and two weeks later I got notice that I was to be transferred to Panama City, Fla. I thought I’d just get down there and have to turn around and come home again, so I resigned.

How did it feel to finally be classified as military veterans in 1977?

I hadn’t thought about it for years. We had reunions every five years, and I went to most of them—but it was just to get together. It wasn’t until an article came out in the paper about the first woman to graduate from the U.S. Air Force Academy and fly military planes. That stirred things up, and we started circulating petitions then asking for recognition. Senator Barry Goldwater and General Arnold’s son [Colonel Bruce Arnold, U.S. Air Force, Ret.] were very active in supporting that effort.

What do you want people to remember about your service and the WASP program?

I want them to know we existed and were there to help during the war when needed. When we weren’t needed anymore, they just sent us home. The way the situation was handled wasn’t really fair. We were hired as civilians, and we knew it when we went in. But when we went in, we were more or less promised we would be taken into the military. It left a bitter taste.

During a recent talk I said, “When you say the word wasp, people think of an insect.” Now I’d like to get the word out in small groups, to let them know we did exist. We weren’t combat heroes or anything, but we were part of the war effort.

How do you feel about women serving in the military?

I think there’s a place for them in the military, and I think they should be treated with respect for the job that they’re doing. And I am glad they are accepted now as much as they are. MH