By mid-April 1945 the war in Europe was rapidly winding down. The Soviets were fighting in the suburbs of Berlin and had occupied much of the eastern region of Germany to the north and south of the city. From the west, American and British forces were moving swiftly across central and southern Germany. Lieutenant General George S. Patton’s Third Army was closing on the Czechoslovakian border. It was obvious to all that the final collapse of German ground forces was only a matter of days away.

Still, the air war continued unabated. Bombing missions were being flown nearly every day, although substantive strategic targets were harder to find. While the Luftwaffe still had a large number of fighters, many of them Messerschmitt Me-262 jets, it lacked sufficient fuel and experienced pilots to seriously oppose the Allied bombers. Allied fighters controlled the skies over Europe, but German anti-aircraft defenses were still murderously effective. The U.S. Eighth Air Force was therefore faced with the problem of identifying targets of sufficient strategic importance to warrant risking airmen’s lives.

One of the few major industrial plants not yet damaged by allied bombing in April 1945 was the Skoda Armament plant at Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. Long a potential strategic target, it had not been bombed because of its location within a Czech city. The Skoda plant produced tanks, heavy guns and ammunition, but most of that materiel appeared unlikely to reach the front in time to have an effect on the Allied advances. At the outset, therefore, the Skoda plant did not seem a target worthy of the risk, but other factors came into play among the Allied leaders.

By spring 1945, it had become obvious at the higher political levels in Britain and the United States that the Soviets were positioning themselves to lay political claim to as much of postwar Eastern Europe and Germany as possible. It was also assumed that the Soviets would strip all usable equipment from factories in the territories it occupied and ship it home to rebuild the Soviet Union’s postwar industry — and its military strength. Destroying the Skoda plant would deny its machinery to the Soviets. The Western Allies also believed that a demonstration of Allied aerial might, such as a bombing mission that deep into Europe, could deter Soviet ideas of continuing their drive westward from Germany.

Although the request for a bombing mission to Pilsen came from General Dwight D. Eisenhower at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces, the aforementioned political factors most likely weighed heavily in the decision that resulted in Field Order 696. Sent out from the Eighth Air Force at 2323 hours on April 24, the order specified a strike on the Skoda plant. From the outset, the mission was problematic. There were about 40,000 men and women employed at the plant — primarily Czech civilian and conscripted laborers, whose wholesale deaths would damage postwar goodwill between Eastern Europeans and the Western Allies. Consequently, North American P-51 Mustangs were dispatched to Pilsen on the 24th to drop leaflets warning the workers to stay away from the factory the next day. That night, the British Broadcasting Corporation radioed a warning to the Czech workers. On the morning of April 25, Allied Headquarters released another bulletin over the BBC: ‘Allied bombers are out in great strength today. Their destination is the Skoda works. Skoda workers, get out and stay out until the afternoon.’

Field Order 696 sent eight groups of Boeing B-17s of the 1st Air Division to Pilsen. Ten groups of Consolidated B-24s from the 2nd Air Division were targeted for rail centers at Salzburg, Bad Reichenhall, Hallstein and Trauenstein. Nine groups of B-17s in the 3rd Air Division were also slated to drop food supplies to several German-occupied Dutch cities during the afternoon of the 25th, but that mission was later canceled because of adverse weather conditions.

In the 1st Air Division, the 40th Combat Wing dispatched its 92nd Bomb Group as the division lead, with the 305th Group following. Lieutenant Colonel William H. Nelson was the 1st Division air commander. The other two combat wings each sent all three of their groups: From the 41st came the 303rd, 379th and 384th groups, while the 1st Wing sent the 398th, 91st and 381st groups. The 92nd and 398th groups each put up four squadrons, while the other groups sent out the usual three squadrons.

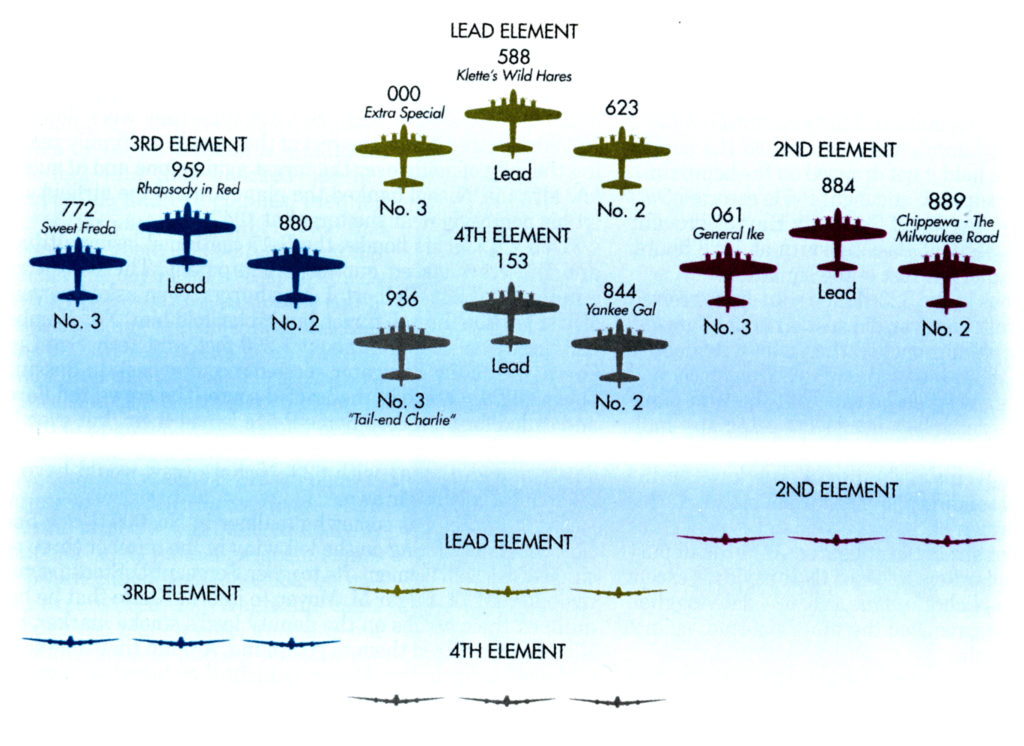

While the other bomb groups attacked the Skoda plant, the 91st, flying out of Bassingbourn, was to attack the airfield at Pilsen, where Allied reconnaissance planes had observed about 100 German aircraft, including Me-262s. The 91st’s formation included the 322nd Squadron, flying as group lead; the 323rd, flying as high squadron; and the 324th, flying as low squadron. Lieutenant Colonel Donald H. Sheeler, who was flying as co-pilot with Captain Rayolyn W. Schroeder’s crew, was the group lead. First Lieutenant Leslie S. Thompson, Jr., served as the first pilot of squadron lead for the 323rd Squadron.

The crews were awakened for breakfast at 0200, then briefed an hour later. The bombload for the lead and low squadrons was 20 250-pound general purpose bombs, while the high squadron aircraft each carried six 500-pound general purpose bombs and four M-17 incendiaries. The aiming point (AP) for the 322nd and 324th squadrons was the center of Pilsen’s runways, while the 323rd was to aim for the west hangar on the south side of the field. The crews were told to make every possible attempt to keep their bombing patterns within the target area, avoiding nearby civilian areas. Bombing on the primary target was to be visual only, with bombing altitudes for the lead squadron at 22,000 feet, the high squadron at 22,500 feet and the low squadron at 21,500 feet.

The secondary target was a visual run on the railway traffic center on the east side of Munich. The aiming point for the 322nd lead squadron was the goods depot, while the high 323rd Squadron targeted the main station, and the low 324th Squadron aimed for the bridge over the rail yards. The number three target was the main railway station in Munich.

A scouting force with call-sign ‘Buckeye Black,’ consisting of six P-51 fighters, would provide information on the local weather conditions to Colonel Nelson 45 minutes prior to time over target. A screening force of four aircraft, call-sign ‘Small Leak Blue,’ would rendezvous with the 91st Group’s lead flight at 0955, 40 minutes from the primary target. The target to be attacked would be determined at that time. Upon receiving that information, Small Leak Blue would accompany the group lead to the appropriate initial point (IP, the beginning of the bomb run), where the screening aircraft would pull ahead and drop chaff in the target area.

The 324th Squadron crews were at their planes at 0430. While 1st Lt. William Steffens’ crew was going through its preflight checks, sergeant William L. Swanson, the radio operator, tuned in to the BBC and heard its message to the Skoda workers. The planes started their engines at 0515, and the group lead aircraft took off at 0530. First Lieutenant William J. Auth’s lead plane of the 324th Squadron became airborne at 0540. All 324th planes were in the air by 0605.

Although ground fog and high cloud cover over East Anglia made it difficult to see very far, weather was not a major problem for the 91st Group as its lead aircraft reached the assembly altitude of 5,000 feet at 0540. All the 91st aircraft were in formation and left the base area at 0642, only one minute behind schedule. As it happened, however, someone else in the 1st Combat Wing was using the 91st Group lead’s call sign, hampering communications. Further, the 602nd high squadron of the 398th Group, just ahead of the 91st, continually flew wide and back, making it difficult for the 91st’s B-17s to stay in formation and maintain the proper separation. At 1022 — four minutes before the IP — the 1st Division reached the bombing altitude of 22,000 feet. About halfway through the climb, the 382nd Group passed the 91st, relegating it to the eighth and last place in the strike force.

Radio operators in many of the 91st planes listened in on the BBC to break the monotony of the long flight. At about 0930, just an hour before they reached the target, the BBC once again sent warning messages to the Czech workers in the Skoda plant.

Up to that point, the mission was progressing routinely. As the strike force approached the target, however, things became confused. For starters, the P-51 scouting force had gotten lost and reported conditions over Prague instead of over Pilsen. Conditions were worse over Pilsen, but the bomber crews discovered that only as the lead group approached the target — too late to switch to the secondary target. Further, the Germans had obviously heard the BBC’s warnings to the Czech workers and alerted their anti-aircraft gunners. Tracking flak began hitting the strike force about three minutes out from the target and ended just beyond ‘bombs away.’ As the first groups went over the target, the flak was designated as ‘meagre and inaccurate.’ The German gunners did not yet have the proper range.

Because of the dense cloud cover, the lead squadron bombardiers had trouble identifying their APs. In the 92nd Group, the lead squadron bombardier could not see the AP, so the squadron made a 360-degree turn to the right, going over the target and through the flak once again. That group dropped its loads on the second run. The high squadron also failed to see its AP at first and also made a second run. Both the low and low-low squadrons had to make two complete turns before spotting their APs, finally dropping on the third run over the target. None of the three lead bombardiers in the 305th Group spotted the AP at first, and the entire group dropped its bombloads.

The 41st Combat Wing’s groups experienced similar trouble. All three squadrons of the 303rd Group failed to locate their APs on the first run. After making a 360-degree turn and picking an alternate AP, all squadrons bombed on the second pass. The 379th Group’s lead squadron also made a second run. Both the low and high squadrons managed to see their APs and dropped on the first run, then headed back from the rally point without waiting for the lead squadron. After completing its second pass, the lead squadron joined the 91st Group for the return trip across the Continent.

None of the 384th Group’s bombardiers identified the AP on their first pass. On the second run the lead and low squadrons dropped, but the high squadron had to make a third pass. The last 384th Group planes dropped at 1116 — presumably the last bombs dropped on Europe by the Eighth Air Force. The lead and low squadrons circled near Frankfurt until the high squadron caught up with them for the trip back to their home base at Grafton-Underwood.

In the 1st Combat Wing, none of the four squadron lead bombardiers of the 398th Group could find his AP, and all had to make a second pass. As the last group, the 91st, approached the target, its crews saw utter chaos ahead. Squadrons and entire groups were turning around and then trying to find space to wedge back into the bomber stream for another pass. Other squadrons were circling at their group rally points, waiting for their sister squadrons to join them.

The 324th crews saw many planes going down, including; from the lead 92nd Group, No. 369 with Lieutenant Lewis B. Fisher, six of whose crew were killed in action; from the 305th Group, No. 300, Lieutenant Gerald S. Hodges and his crew; from the 303rd, No. 447, piloted by Lieutenant Warren Mauger (three KIA); from the 384th Group, No. 501, piloted by Lieutenant Andrew G. Lovett; from the 398th Group, No. 266, piloted by Lieutenant Allen F. Fergusen, Jr. (six KIA); and No. 652, piloted by Lieutenant Paul A. Coville (one KIA). In addition, two aircraft from the 379th Group — Lieutenant James M. Blain’s No. 178 and Lieutenant Robert C. Evans’ No. 272 — collided in midair as a result of flak damage. Both planes went down in Allied territory. All nine crewmen aboard Blain’s plane, Seattle Sue, and the tail gunner aboard Evans’ The Thumper were killed. A number of planes also fell out of formation because of disabled engines or fires aboard.

Anti-aircraft fire became more accurate with each bombing run. As crews of the 324th Squadron later recalled, by the time the 324th approached the target, the flak was among the most accurate and intense they had encountered on any mission, including over Berlin. The 324th’s formation became exceptionally tight as it headed in over the target.

In spite of the heavy cloud cover, the lead bombardier in No. 852, 1st Lt. Stephen Lada, got a visual fix on the AP and dropped his bombs. The rest of the squadron toggled on his smoke streamer. Just after bombs away, hits on No. 306, The Biggest Bird, flying as the lead plane in the fourth element, knocked out both right engines, disabled the supercharger on an engine on the left wing and severed the rudder control cables. To make matters worse, when Staff Sgt. Francis N. Libby toggled the bombs, 11 of the 20 250-pounders in the aircraft hung up. With only one functional engine, pilot 1st Lt. Robert Marlow took the plane down to the deck to regain power in the engine without the supercharger. Although the crew dumped out all the loose equipment they could locate, it became clear the aircraft would not make it back to Bassingbourn. They could not jettison the bombs, since by then they were over occupied Allied territory. Instead, they pinned them to prevent them from becoming armed, while Marlow looked for the nearest emergency field. He finally put down on a grass airstrip about 50 miles north of Nuremberg — only to discover that his brakes no longer functioned. The Biggest Bird careened over the grass, ground-looped and eventually came to rest in some woods. U.S. Army ground troops came by in a jeep as the crew got out of the plane and told them to hide in the woods to avoid German civilians. A truck soon arrived and picked up all of Marlow’s crew. They returned to Bassingbourn three days later, the last 91st crew to return from a mission over Europe.

Second Lieutenant Glennon J. Schone’s plane, No. 790, Oh Happy Day, flying as the ‘tail-end Charlie’ of the lead squadron, was hit by flak just before bombs away. Damage was minimal, but a fragment about the size of a half-dollar embedded itself in the right thigh of the navigator, 2nd Lt. Arah J. Wilks. Both No. 596, Sweet Dish, and No. 308, Stinky, were hit hard but remained in formation and safely returned to base.

As the other two squadrons came over the target, neither of the lead bombardiers could locate his AP, so the lead planes did not make their drops. The high squadron lead, 1st Lieutenant Leslie S. Thompson, Jr., in No. 630, Geraldine, ordered the squadron to make another run. The radios went wild. Second Lieutenant Willis C. Schilly, a pilot in No. 964, later recalled thinking to himself, ‘If we don’t drop this time, I will not go over again.’ Aboard Number 540, Ramblin’ Rebel, there was some discussion between 1st Lt. Leland C. Borgstrom and his unhappy co-pilot, Flying Officer Quentin E. Eathorne, but they made a second run. Other pilots and crews were equally upset, but all stayed in formation. Because the return leg of the 360-degree turn they had to make was close to the target as well as the flak, many crewmen later said they thought they had made three runs instead of two.

During the first bomb run, number 636, Outhouse Mouse, on her 139th mission and with 1st Lt. Elmer ‘Joe’ Harvey serving as first pilot, took a flak hit that knocked out her number three engine and severed all but two of the elevator control cables. Crewmen patched together the cables, and she stayed in formation as the 323rd went over the target again. However, when her bombardier, Staff Sgt. Edward L. Loftus, hit the toggle switch, her bombs hung up. After the second run, Outhouse Mouse had to drop out of formation. Thirteen minutes after leaving the target, Loftus accidentally jettisoned the bombs (they were supposed to be held if not dropped on the bomb run). Harvey called for fighter support, and eight P-51s escorted Outhouse Mouse most of the way out of Germany. Harvey brought Outhouse Mouse down safely at Bassingbourn at 1428 hours, about half an hour ahead of the rest of the squadron.

None of the other planes in the 323rd high squadron received major damage. Six aircraft, however, did sustain minor damage.

As the 324th Squadron approached the factory, its deputy lead bombardier in No. 884, 1st Lt. Joseph G. Weinstock, had the target in his bombsight when he saw that the lead plane did not drop and that its bomb bay doors were going up — indicating that it was aborting its bomb run. At that instant, a shell burst next to the nose of Weinstock’s aircraft, knocking out the number two engine and sending a large shard of metal into his shoulder. As he was thrown backward, Weinstock toggled his bombs. When the smoke streamer appeared from the deputy lead, all of the other bombardiers released their payloads except the one on 1st Lt. John Nichol’s plane, No. 623. His togglier, Tech. Sgt. Joseph J. Zupko, realized the squadron lead had not dropped and held the bombs.

As the low squadron lead plane — No. 588, Klette’s Wild Hares — went over the target, her bombardier, 1st Lt. Robert E. Finch, said he could not see the AP. Lieutenant Colonel Immanuel ‘Manny’ Klette, the 324th’s commanding officer — who was flying as the squadron leader — told 588’s pilot, 1st Lt. William Auth, ‘Well, we’ll go around’ and started closing the bomb bay doors. Auth then started to turn, at which point Klette broke radio silence to tell the other pilots to follow him back over the target.

Pandemonium broke loose on the radio as the other pilots told Klette that they had dropped. Someone told him, ‘If you are going back over again, you are going alone.’ With all the pilots yelling at once, it was unclear exactly what Klette heard, but he came back on the air, telling them to be quiet. Then he added: ‘We are going around again. I don’t want to discuss this. It’s an order.’ None of the pilots said anything at that point, but after they had turned roughly 180 degrees, the other planes still flying at the bombing altitude scattered.

When the number two plane in the lead element, Nichol’s No. 623, went over the target it took a flak hit that knocked out her number one engine and blew part of the cowling from engine number two — which soon went out. Nichol tried to go on around with Klette, even though his plane was falling below the formation. When the co-pilot, 1st Lt. Lawrence E. Gaddis, realized what Nichol was doing, he yelled over the intercom that he was taking over the plane and that they would not go through that flak again. He also asked someone to come up and get Nichol out of the pilot’s seat. One crewman who agreed with Gaddis grabbed the landing gear crank and went into the cockpit, while the others yelled over the intercom for Nichol to abort his 360-degree turn. By that time they were down to 18,000 feet, well below the rest of the squadron. Finally realizing the folly of going over the target again alone and at such a low altitude, Nichol banked the plane around the airfield and let his bombs fly near the target at 1047.

Even without its bombs, the B-17 continued losing altitude and the crew tossed out loose equipment. The ball-turret gunner, Staff Sgt. Delbert J. Augsburger, even asked permission to jettison the ball turret, but Nichol told him ‘No.’ Number 623 finally leveled off at about 7,200 feet, and Tech. Sgt. Carl Greco, the acting navigator, plotted a course back to Bassingbourn slightly north of the briefed route. The crew fired flares and called for an escort. Some P-51s joined them, but even by lowering their flaps and wheels, the fighters could not slow down enough to stay with 623. Nichol’s crew would have to make it back on their own.

The situation was somewhat calmer in No. 000, Extra Special, which was flying on the left wing in the number three position of the lead element. Its togglier, Sergeant D. Stockton, told the pilot, 1st Lt. Edgar M. Moyer, to inform Klette that he had dropped their bombs on the deputy lead’s smoke marker, but Klette still ordered them to go around. Around that time some of the pilots, including Moyer, thought they heard someone on the radio say that anyone who had dropped their bombs could join up with another group for the return trip. Accordingly, Moyer broke formation and, sighting planes from the 305th Group rallying nearby, headed toward them. Since the Germans were known to infiltrate formations in captured B-17s, it took some time before the 305th allowed Extra Special to join up. When the group reached England, Moyer flew on to Bassingbourn, arriving about 45 minutes before the rest of his squadron.

Leading the second element, No. 884, piloted by 1st Lt. William E. Gladitsch, took flak hits that knocked out her number one and two engines, then fell out of formation. Number 884 had dropped to about 10,000 feet when her number one engine started up again. By having his crew throw out all the equipment, including the .50-caliber machine guns and the radios, Gladitsch was able to maintain that altitude. He broke radio silence and got Klette’s permission to return to England, flying slightly behind and below the 91st Group.

As 2nd Lt. Armando P. Crosa’s plane — Chippewa-The Milwaukee Road — went over the target, it was buffeted badly by what ball-turret gunner Sergeant James H. Wyant called the worst flak he had ever experienced. Two fragments came through the plane’s nose, knocking out the Plexiglas and putting holes in the fuselage and wings. Assuming the worst, Wyant rotated the ball turret to the exit position and went up into the fuselage, so he could reach his parachute. Somehow Chippewa got through without serious damage, however, and Wyant climbed back into his turret to watch for German fighters. Crosa started to join Klette in his turn, but eventually he broke formation, along with six or seven other planes.

As 1st Lt. John L. Hatfield’s plane, No. 061, General Ike, approached the target, her crew saw several planes going down. Sergeant Emil A. Kubiak, in the ball turret, tried to call out the flak bursts. General Ike made it to the target without major damage, and Sergeant Vernon E. Thomas triggered the bomb release on the deputy lead’s smoke streamer. At the same time, the flight engineer, Sergeant Victor Maguire, Jr., hit the salvo switch and Hatfield pulled the bomb release in the cockpit. Just after the bombs fell away, a flak burst hit the bomb-bay doors, which refused to close. The tail gunner, Sergeant Alfred G. Miller, plugged in his ‘walk-around’ oxygen tank and came up to help Maguire crank up the doors, while the radio operator, Sergeant Vincent W. Karas, went back and manned the tail guns. As the doors came up, the crew realized there was a fire in the bomb bays. Smoke started filling the plane, adding to the confusion caused by the bursting flak. Maguire pulled wires while Miller put out the fire.

Hatfield went partway around with Klette, but he broke formation around the same time that others in the squadron did. General Ike made a tight 360-degree turn inside the other planes about a mile south of the target and started home alone. Shortly after leaving the target area, one of the crew reported bandits closing in, but they proved to be Mustangs. Once they were over Allied-occupied territory a couple of other planes, with feathered engines, joined up with General Ike to continue on back to Bassingbourn.

In the third element, 2nd Lt. Woolard’s lead plane — No. 959, Rhapsody in Red — dropped on the deputy lead smoke streamer at 1037, but the aircraft was hit very hard by flak. One engine was knocked out and another could only generate half power. A piece of flak imbedded itself behind the pilot’s seat, knocking out the hydraulic system. Rhapsody in Red was forced to drop out and return alone.

Flight Officer Louis Schaft’s B-17 No. 880 also dropped its bombload with the deputy squadron lead at 1037, suffering only a few minor flak hits. Schaft made a 180-degree turn before deciding to break formation. He formed up on some other planes that were still flying at the briefed altitude and returned to Bassingbourn without incident.

First Lieutenant William P. Steffens’ plane — No. 772, Sweet Freda, flying on Woolard’s left wing — dropped with the deputy lead at 1037 and took only a few flak hits. Steffens stayed with Klette through the first part of the turn, relaying what Klette was saying to the rest of the crew over the intercom. The crewmen started screaming at Steffens not to go around. Then he too broke formation about halfway around to the target and formed up with other returning 324th Squadron planes.

Staff Sergeant Samuel S. Castiglione toggled No. 153’s bombs with the deputy plane at 1037, but nine of them got hung up. While over the target, a shell exploded on the right side of the B-17, knocking out the number three engine, putting a number of holes in the nose and wing, and nearly severing a wing spar. Flak went through the ball turret, barely missing Sergeant John F. Unger, and also damaged the tail. Number 153’s pilot, 1st Lt. George S. McEwen, feathered the number three engine and managed to maintain altitude. McEwen joined Klette as he started his turn, but broke formation before his crew started to panic. His crew pinned the hung-up bombs and returned with them.

Second Lieutenant Earl C. Pate’s No. 844, Yankee Gal, took a lot of small flak hits but suffered no serious damage. Staff Sgt. George D. Kelly released her bombs at 1037. Pate followed on McEwen’s right wing halfway through the turn but broke formation before his crew understood that Klette had ordered another run over the target. Joining the first 324th plane he saw for the trip home, Pate did not see McEwen’s plane the rest of the way back.

Things were much more frantic among the crew of the tail-end Charlie, 2nd Lt. Raymond W. Darling’s No. 936. The plane took only minor hits over the target, dropping her bombs at 1038, and as it rallied to the right, the crew breathed a sigh of relief. Then the pilot switched the radio to the intercom so the crew could hear Klette’s order. Afterward Darling switched off the radio and asked for a vote. The tail gunner, Staff Sgt. Wayne E. Kerr, said on the intercom: ‘Lieutenant, I’m married and I have a little boy. I’m not going through that again. If you go around, I’m bailing out.’ Darling told the crew, ‘We’re not going over again,’ then banked sharply to the right. His crew was ecstatic. A few other planes formed up on No. 936 as they reassembled in the homebound 91st Group formation.

When the other 324th Squadron planes broke formation, the tail-gunner of the lead aircraft, Staff Sgt. Charles L. Coon, came in on the intercom to inform Klette that No. 588 was now alone. Klette said, ‘We’ll put the pins back in the bombs and go home.’ Klette was quiet the entire flight back to Bassingbourn.

Strike photos from the 323rd showed good bombing results for the high squadron. Because of the dense cloud cover, however, it was unclear what damage had been done by the lead and low squadrons. It was learned later that 70 percent of the Skoda plant had been destroyed. Only six workers were killed, but bombs also fell in a nearby residential area, killing 67 people and destroying 335 houses. In addition, 17 German anti-aircraft gunners were also killed.

After rallying to the right off the target, the 322nd lead squadron made a large oval turn in an attempt to allow the 323rd high squadron to complete its second bomb run and get back into the formation. The rally point, near Wurzburg, was adjacent to the southern arc of the oval. The planes spread out low, with the 324th Squadron still at the bombing altitude, and the 91st Group formation also made the turn with the lead squadron. But the 323rd was too late in coming off the target to get into its proper position, and followed along behind.

Although six of the 324th Squadron’s 12 aircraft had sustained major damage, all but two made routine landings at Bassingbourn. As Woolard’s Rhapsody in Red crossed over the English coast, one of his engines was out and another pulling only one-half power. Further, the hydraulic system was knocked out, the landing gear electrical system was not working, and the wheels had to be hand-cranked down. Woolard radioed Klette, requesting permission to land at Alconbury’s longer runway. Klette replied that he would have to land at Bassingbourn or ‘not at all.’ So it was on to Bassingbourn. With no brakes, Rhapsody in Red rolled off the runway and veered to the right across the grass to her hardstand area, hitting the ground crew’s tent with her wing as she spun around. She finally came to a stop with only minimal damage to the aircraft. The ground crew chief, Staff Sgt. John A. Mabray, was apparently more afraid of damage to ‘his plane’ than he was concerned about the flight crew, but Woolard had done a good job of getting the B-17 down. It was his plane’s last mission, as well as his own.

Nichol’s fuel was so low that he only had time for a straight-in landing with the wind, but even so he managed to put the damaged aircraft safely down on the runway. As his crew got out, Nichol was ordered to report to the control tower immediately. He anticipated being commended for making such a good landing under the circumstances. Instead, he was chewed out for landing downwind.

Shortly after debriefing was over, the 324th crews returned to their billets. Then all first pilots were ordered to report to the squadron orderly room. There, 10 of the 11 pilots faced a fired-up Klette, who called them all ‘yellow-bellied SOBs’ and claimed the war would have been lost long ago if they had been running it. He said he did not care if they had dropped their bombs — he had ordered them to go over again with him. Klette told the pilots he was going to court-martial five of the ones he felt had been most responsible for breaking formation, and that he was adding five missions to the 35-mission quota for all first pilots who had broken formation. He did not give anyone a chance to explain. Klette also went after the deputy bombardier. Although Weinstock held Klette in high esteem as a combat leader, they had had personal differences ever since Weinstock had arrived in the squadron.

The pilots were devastated, and some felt sure the extra missions amounted to a death sentence. Several were only two or three missions away from finishing their tours. After Klette left, Auth, the lead pilot, tried to calm the others, saying: ‘Don’t worry about it. There will not be five more missions before the war is over.’ He also told them Klette could not make the additions stick — higher headquarters would not approve it.

Auth proved to be right. Pilsen was the last mission the Eighth Air Force ever flew. None of the penalties that Klette threatened were ever instituted, and the entire incident was hushed up. Only Lieutenant Moyer’s debriefing report indicated that he did not return ‘as briefed.’ The section of the debriefing form asking whether or not the plane returned ‘as briefed’ was left blank for the other planes. The debriefing records indicate that Klette’s lead plane dropped its bombload at 1036, essentially the same time as the rest of the squadron.

A report by 2nd Lt. Edward J. Drake, a pilot from the 401st Squadron on the April 25 mission, clarified a little of what actually happened. Drake correctly recorded that the 324th was’scattered in flak’ at 1100, 44 minutes after its bombs had been dropped. At 1115 he could see neither the 324th low squadron nor the 323rd high squadron. At 1200 Drake recorded only that the 324th formation was a ‘little loose’ and that the second element was ‘flying too far out, probably because of battle damage.’ At 1230 he recorded that the squadron was still flying ‘loosely,’ with the right wing of the second element ‘too far out and back.’ At 1300 the second element was still ‘too far back.’ At 1330 the 324th formation was ‘not too good,’ with the second and third elements flying was ‘too far out.’ At 1400 hours all elements except the lead were ‘out of formation.’ At 1430 the second element was ‘too far out’ and the fourth element ‘much loose.’ He gave the lowest ranking of the three squadrons to the 324th for formation flying on this mission.

Drake, who did not identify individual planes in his records, was understandably confused. Only eight 324th planes in the formation were flying at the prescribed altitude. Three, Nos. 884, 623 and 959, came back alone or well out of the formation. In addition, No. 000 joined up with the 305th Group for the return flight. Lead squadron planes of the 379th Group may have also been flying with the 324th planes, adding to the confusion.

Crewmen who flew on the Pilsen mission remember it as one of the most chaotic and frightening sorties they had flown. With so many squadrons making additional bombing runs (there were 52 separate squadron passes over the target), German anti-aircraft fire against late-arriving squadrons became more dangerous as time went on.

All the 324th crews acted correctly as they went over the target. The lead bombardier could not identify the AP and gave the proper signal for the rest of the squadron not to drop and to start a 360-degree. The deputy bombardier thought he had identified the squadron AP, and he saw that the lead plane seemed to abort its bomb run at the same instant when he and his plane were hit by flak. His actions — dropping his bombs and smoke streamer — were standard operating procedure, a fact that Klette admitted to him years later. Because of all the confusion and flak on the bomb run, however, toggliers in the other planes were concentrating on watching for the smoke streamer. When one appeared, they immediately toggled their bombs, as they were supposed to.

What followed the bomb run is more questionable. Should Klette have ordered the 360-degree turn? Obviously, from the vantage point of more than 50 years of hindsight, it’s tempting to make snap judgments about Klette’s actions. The initial order for a second run over the target was appropriate — the lead plane had not dropped, and Klette could only assume the others had not dropped either. Most other squadrons in the strike force were doing the same. But should Klette have continued his turn after being informed that the other planes in the squadron had dropped their bombloads? With so many pilots yelling over the radio at once, it seems likely that Klette did not understand. In fact, he later said that he did not know they had dropped.

Should the pilots have broken formation? All except for Nichol’s plane had accomplished their missions. Was it worth risking the lives of the 98 crewmen in the squadron to drop an additional 4 tons? As it was, 26 crewmen in the other seven groups were killed. The pilots’ reactions were appropriate under the circumstances.

Klette’s threatened reprisal against the pilots for breaking formation was understandable. A highly respected squadron commander, he had flown more bombing missions than any other pilot in the Eighth Air Force. It was only natural that he would consider the pilots’ actions a reflection on his leadership. What is not clear, however, is how much of his tirade was intended to make a point and how much he really meant to follow through with. That he had been quiet on the long flight back from Pilsen suggests that much of his tirade may simply have been a way of venting his frustrations.

In the final analysis, however, all the confusion about the Pilsen mission became merely an unrecorded footnote in the 91st Bomb Group’s history. No damage had been done. All the crewmen returned. Not one of the threats was carried out, and Klette never brought up the incident again. The mission’s chaotic events were soon relegated to the crewmen’s memories, brought up only decades later during late-night sessions at 91st Bomb Group reunions. But the strange story of how the war ended for the 324th Squadron needs to be preserved, and should not disappear with the participants.

This article was written by Lowell L. Getz and originally published in the January 2003 issue of Aviation History.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!