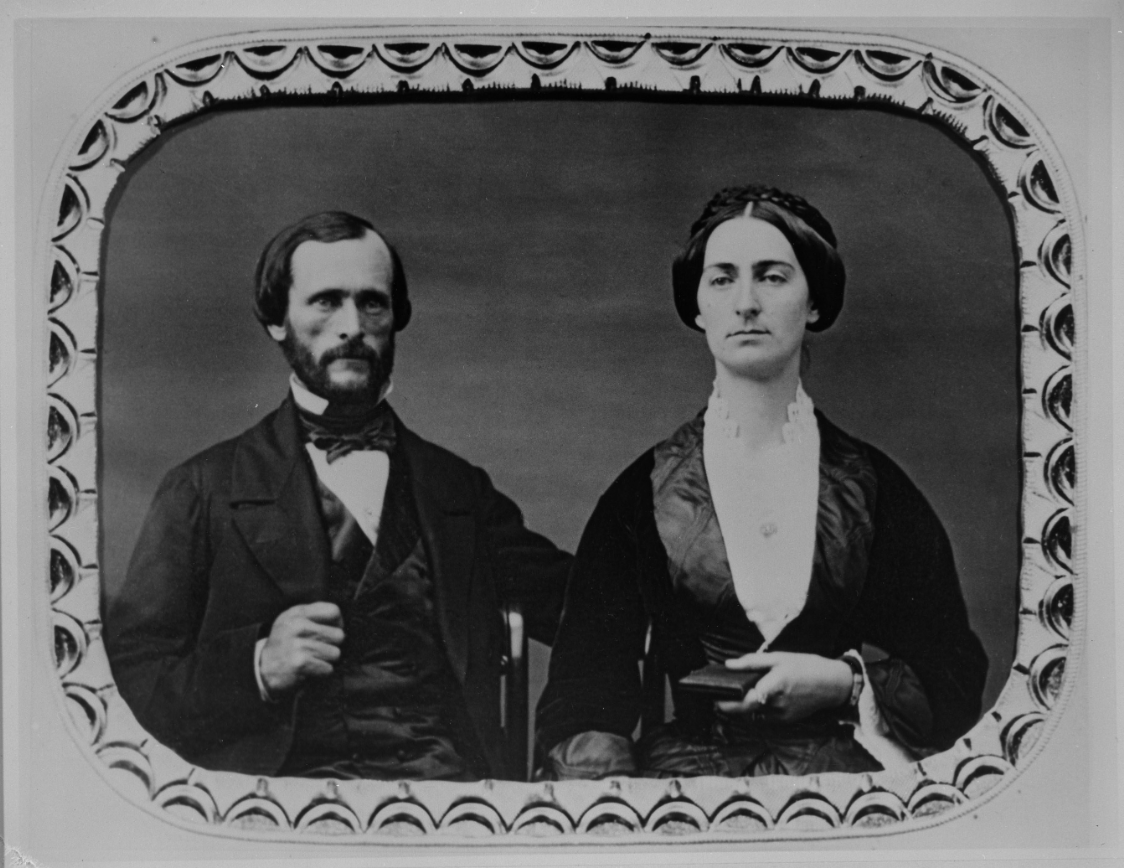

Witnesses and participants in the defining moments of 19th-century American expansionism, John and Jessie Frémont maintained a marriage and an ideological vision ahead of its time.

The 27-year-old blue-eyed explorer, fresh from an expedition to the American West, was the illegitimate son of a French Royalist émigré and a runaway Southern belle. The 15-year-old raven-haired girl, now drawn to the handsome uniformed officer, was the daughter of Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, one of the country’s most powerful antebellum senators.

It was February 1840, in the drawing room of an upper-crust female seminary in Georgetown, District of Columbia, and the young lady welcomed her father’s introduction. “May I present Lieutenant John Charles Frémont,” Benton said.

Jessie Ann Benton extended her hand to the gentleman, whose slight stature was oddly imposing, his tanned face and flashing white teeth rarities for the time and place. John brushed Jessie’s hand with his lips and was equally smitten, struck by what he called her “girlish beauty and perfect health.” From that moment, the couple was passionately, fatefully, historically enmeshed—John her “very perfect gentle knight,” Jessie his “rose of rare color.”

The romance and alliance, passion and principle initiated that day in Washington would impact the very nation, from the founding of a new political party to the country’s torment of Civil War and slavery. Never before had a political couple so fascinated and baffled the American public. Essence and symbol of the defining moments of 19th-century expansionism, John and Jessie Frémont were the quintessential American power couple.

Benton, the man who unwittingly bound John and Jessie together, had been courting Frémont to realize his own vision of the nation’s bounded expansion. A towering frontiersman, Benton would become the champion of Manifest Destiny. Jessie was her father’s consort and collaborator, his apprentice and creation. Known for her magnetism and beauty, she had already received two marriage proposals, including one from President Martin Van Buren, prompting Benton to cloister her in the then-rural seminary run by Miss Lydia English.

Benton took Jessie quail hunting, introduced her to birdwatching with his friend John Audubon, taught her five languages and impressed upon her the importance of disciplining her mind and exercising her body. She spent long hours at the congressional library, poring over Thomas Jefferson’s 6,000-volume collection of books. From her earliest years, Jessie accompanied Benton to Senate debates. And she was as comfortable in the White House as in her own home, where Andrew Jackson would tangle the child’s locks with his fingers while discussing politics with her father— one of Jackson’s strongest supporters in building the Democratic Party. By her mid-teens Jessie was as trained and astute a politician as any young man her age. A later president, James Buchanan, would call her “the square root of Tom Benton.” But suddenly there was a competing element in the father-daughter dynamic, and the senator was noticeably alarmed by the instant attraction between Jessie and John.

Benton himself had become enamored with the engaging Frémont, who had just explored the plateau country between the Mississippi and Missouri and was in Washington to report his findings to Van Buren. The young surveyor was ensconced at a Capitol Hill town house where his mentor, the distinguished astronomer Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, had built an observatory. Frémont was creating an enormous map of his recent findings, and Benton, intoxicated by a desire to probe the Western frontier and open trade routes to the Far East, saw the young man as a means to that end.

Still, Benton never imagined his daughter would fall in love with Frémont, who had courage and a spirit of adventure but was a poor man of dubious breeding and background. “We all admire Lieutenant Frémont,” Benton told his daughter, “but with no family, no money and the prospect of slow promotion in the Army, we think him no proper match for you. And besides, you are too young to think of marriage in any case.”

But the powerful senator was powerless to keep the couple apart. Jessie and John began a surreptitious correspondence and discovered like minds who shared a passion for books, exploration and, not least, Thomas Hart Benton, who inspired them both. Still, the senator’s objections only heightened the couple’s ardor and sense of injustice.

Jessie and John were secretly married on October 19, 1841. When Benton learned of their elopement, he sat stonily in his chair, refusing to meet Jessie’s eyes while staring, enraged, at John. She watched as her new husband, usually brave and articulate, fumbled and sweated. Neither was fully prepared for Benton’s reaction. “Get out of my house and never cross my door again!” he railed at John. “Jessie shall stay here.” With that, Jessie defied her father, locked arms with her husband and quoted the biblical words of Ruth: “Whither thou goest, I will go.”

Benton could not stay angry at his favorite daughter for long, especially as Frémont’s cachet rose in Washington circles with news of his recent successful survey. Benton soon invited them to return to the family’s C Street mansion. In addition to a furnished bedroom, Benton provided the couple with a study—his eye toward their future collaboration as surrogates for his own aspirations. “We three understood each other and acted together—then and later— without question or delay,” Jessie remembered.

Benton’s interest in the West was political, not scientific. But Frémont, while steeped in the discourse of expansionism, was first and foremost a scientist. Much would be made later of his opportune marriage to the daughter of one of America’s most powerful political figures, many scholars dismissing the surveyor’s achievements and crediting Benton for his rise. But the reality was far more complicated. Yes, the senator was a fortunate connection, but when Benton entered his sphere, Frémont was hardly the swashbuckling neophyte many historians have caricatured. When John married Jessie, he was already an expert topographer, a skilled astronomer, a student of botany and geology, an accomplished surveyor and a proven leader of men. To his list of important benefactors he had merely added another powerful patron. The favorable match with Benton’s daughter accelerated a career already destined for success, if not greatness.

John Frémont, who in 1838 had been commissioned a second lieutenant in the newly formed Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, was well trained to meld celestial and terrestrial observations, fix his position and map a route, thanks to singular access to the world’s foremost scientists. In early 1842 he and Jessie threw themselves into preparations for a Benton-supported expedition that would open migration to Oregon. Jessie naturally assumed the role of John’s assistant, secretary and adviser, just as she so ably had done for her father. In that position she also served as a diplomatic barrier between him and the ubiquitous inventors, emigrants, job seekers, politicians and adventurers seeking an audience.

Finally, on a May morning John dressed for that first major expedition in his new blue-and-gold uniform; Jessie, now pregnant, adjusted the braid and buttons and straightened his collar. Both were thrilled yet dreading the impending separation, as their first months of marriage had been supremely happy. Jessie wept at the crowded Washington railway station while friends and colleagues bid farewell to explorer John. Thus began her lifelong role as a patient but anxious wife, awaiting the return of a peripatetic but devoted husband.

John returned to Washington six months later, elated by the success of the expedition. He had raised a modified American flag on a high peak in the Rockies, staking it as a gateway to the West. John was also desperate to see Jessie, who just days after his return gave birth to the first of their five children.

The new father had an eagerly awaited report to write, so Jessie provided him with pens, ink and sheaves of foolscap and left him sequestered, his notes carefully laid out on a table. For three days he agonized, starting and stopping, throwing pages into the fireplace. On the fourth day he admitted to writer’s block. “I write more easily by dictation,” he explained to Jessie. “Writing myself, I have too much time to think and dwell upon words as well as ideas. In dictation there is not time for this, and then, too, I see the face of my second mind and get there at times the slight dissent confirming my own doubt, or the pleased expression which represents the popular impression of a mind new to the subject.” Jessie readily accepted the role of “second mind” for John. “The horseback life, the sleep in the open air had unfitted him for the indoor work of writing,” Jessie told her father and others as she became what John called his “amanuensis.”

The duo was inseparable and synergetic, and their teamwork transformed the expedition into a wonderful adventure and best-selling book. They gave drama to the landscape John had charted and breathed life into the characters—Kit Carson, Arapaho Indians, mountain men, fur traders and scouts. On the written page, the unshaven, rough-hewn explorers became heroes on a visionary quest. For the first time in U.S. history, an explorer’s report related a gripping narrative. It also served as an eminently practical guide for thousands of westbound emigrants, describing the rich soil of the Platte River valley and identifying prime locations where new settlements could be built and crops raised.

John submitted the 215-page document to the War Department, and within days the Senate issued a print order for 1,000 copies. Newspapers nationwide ran excerpts, and literary critics compared the tale to Robinson Crusoe. John and Jessie became the toast of Washington, the Frémont name synonymous with the lure of the West romanticized in George Catlin’s paintings, James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales and Washington Irving’s Adventures of Captain Bonneville. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, fascinated by Frémont’s achievement, drew inspiration from the report for his epic poem “Evangeline.”

There followed several more expeditions—a series of partings and reunions for John (“the Pathfinder”) and Jessie—and service in the Mexican-American War, which culminated in Frémont’s 1847 court-martial, the result of a power struggle between Army General Stephen Watts Kearny and Navy Commodore Robert Field Stockton. Following the Mexican surrender in California, Stockton had named Frémont military governor over Kearny’s objections. Frémont believed his military orders for the California incursion had come from President James K. Polk and the secretary of the Navy and, therefore, determined that his chain of command rested with Stockton. Kearny responded by having Frémont brought up on mutiny charges.

Jessie implored Polk to intervene, initiating a lifelong habit of pleading her husband’s case with various parties. Certain an acquittal would vindicate John and restore his reputation, Jessie nailed down witnesses, gathered documentation, conducted research and developed a strategy for his defense. She took seriously her role as supportive wife, knowing too that insecurities stemming from John’s illegitimacy always surfaced in times of stress, making him turn inward. Jessie’s mission, as she saw it, was to guide his comportment to one of balance, fortitude, stability and sanguinity.

In January 1848, a jury found John guilty. Though Polk quickly pardoned Frémont and ordered him to report for duty, John and Jessie never forgave the government for what they saw as a betrayal, and Frémont resigned his Army commission. Now a private citizen, John turned his attention to California, the golden land of opportunity where he and Jessie could raise a family and pursue his dream of a transcontinental railroad linking the two oceans. To observers, they seemed the classic emigrant family—John in a civilian broadcloth suit, hand in hand with their 6-year-old daughter, his young wife carrying a dark-haired infant. Relying entirely on Frémont’s paltry savings from his Army salary, the family faced severely reduced circumstances. “We were pretty much in the conditions of shipwrecked people,” Jessie later wrote.

They were soon ensconced in an adobe hacienda in Monterey. Jessie saw slavery as the pivotal issue in California statehood and became actively involved in the issue. Whether John was as passionately antislavery as Jessie is debatable. Though a confessed Free-Soil Democrat, John was not overtly political and was widely seen as a creature of Jessie’s own ambitions— objectives she could fulfill only through her husband, constrained as she was by societal and cultural limitations on women. Their Monterey home became the headquarters of the antislavery delegates, with Jessie the unmistakable leader. Forty-eight delegates attended a constitutional convention at the Frémont hacienda in 1849. The following year John became one of California’s first U.S. senators. After a perilous passage across Panama, the Frémonts arrived in Washington in March 1850—the dashing senator and his glamorous wife.

John Frémont distinguished himself as an uncompromising abolitionist, forging coalitions with Northern antislavery men, severing ties with the South and opening a rift with Jessie’s father. John had drawn the short term in the Senate and in late 1850 returned to California to run for reelection. Defeated, he turned his attention from politics to business concerns—a gold mine near Yosemite.

It would be five years before Frémont reentered political life. Seated on a rocky, moonlit beach in the summer of 1855, John reached for his wife’s hand. “Jessie, I’ve been offered the nomination for the presidency,” he murmured. She couldn’t help but recall her childhood visits to the White House, perching on President Jackson’s lap, dining with Van Buren’s sons, candlelight dancing off the walls of the stately rooms as she fantasized about becoming first lady—the highest position available to an American woman. Her euphoria subsided when John outlined two conditions set forth by the Democrats: Frémont must endorse the Fugitive Slave Law, which would return runaway slaves to their owners, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which would extend slavery into Western territories. Both were untenable to Jessie.

Also courting Frémont was the nascent Republican Party, founded by dissident Whigs and Democrats opposed to the extension of slavery. The Frémonts’ choice was clear: They would stand by their principles. Nevertheless, Jessie was terribly apprehensive. On a visceral level she recognized that John would be the Republican candidate and that ties with her Democratic father would be further shattered. It would mean “excommunication by the South,” she recalled, “the absolute ending of all that had made my deep-rooted pleasant life.” Indeed, the 1856 presidential campaign signaled the death knell to the relationship between the Frémonts and Benton. Jessie’s father actively supported John’s rival, Buchanan, and the family breach would never be repaired.

The campaign also marked the first time in American history that women were drawn into the political process. The “Frémont and Jessie” campaign, as it became known, inspired thousands to take to the streets, and their zeal for Jessie was palpable. Seen as a full-fledged partner in her husband’s pursuits, she became an overnight heroine to women who had been disenfranchised since the nation’s inception. Jessie straddled the boundaries of Victorian society—outspoken but polite, irreverent but tactful, opinionated but respectful—a woman so far ahead of her time that other women flocked to her. A devoted wife, dutiful daughter, engaged mother and clear-minded intellectual, the 31-year-old was the embodiment of womanly virtue and feminine power. More than anyone, she recognized her abilities and the limitations imposed upon her by society and culture. “I can say as Portia did to Brutus,” she wrote, “‘Should I not be stronger than my sex/ Being so Fathered and so Husbanded?’” Still, she remained self-deprecating and deferential to both her father and her husband, whom she regarded as heroes of mythic proportions.

The adulation of Jessie began within a week of John’s nomination, when a massive crowd gathered at the New York Tabernacle. A speaker introduced the candidate, extolling his qualifications as conqueror of California and explorer of America’s frontier. “He also won the heart and hand of Thomas Hart Benton’s daughter!” the speaker continued. With that, someone from the crowd yelled, “Three cheers for Jessie, Mrs. Frémont!” There followed the requisite speeches and applause, and when the grandstanding was over, the throng marched half a mile up Broadway in a torchlight procession to the Frémonts’ New York apartment. Once there they yelled for the candidate, and when Frémont appeared on the balcony, they cheered riotously. Soon came a call for Jessie. “Give us Mrs. Frémont, and we’ll go!” someone in the crowd yelled. Jessie finally came to the balcony, sending the crowd into a frenzy. Whether disconcerted or emboldened, she never revealed her reaction to that evening. Disdainful of “speech-giving women” and having been reared in the shadow of a powerful man, Jessie had no female role models to emulate. Still, the historic precedent and foray into feminist activism must have struck her deeply.

The Frémont candidacy exuded celebrity status. Throughout the nation in the summer of 1856, miles-long processions cheered for Jessie and John. In Indianapolis, where 60,000 people marched and marshals were needed to maintain order, a parade float carried 31 young women in white—one for each state—and one girl dressed in black, symbolizing “Bleeding Kansas.” Frémont demonstrations in Ohio and Michigan drew 25,000 and 30,000, respectively. Women poured into the streets in unprecedented numbers, wearing violet-colored muslins in honor of Jessie’s favorite flower and color. One prominent New York minister reported that women in his congregation were copying her hairstyle and mannerisms and naming their babies after her.

Jessie was the behind-the-scenes campaign manager every step of the way. Buchanan exploited that fact and pointed with alarm to the mass participation of women. In one of the dirtiest elections in U.S. history, the Democrats slandered the couple for their progressive beliefs and broadminded lifestyle. The campaign was inseparable from the abolition movement, which was tearing apart the nation. The Frémonts’ radical view that America should be a true social and economic democracy in which blacks also merit civil rights generated powerful forces against them. None other than Thomas Hart Benton, Jessie’s father, led the smear campaign. In the end, the Republican Party had neither the money nor the political machine in place to fight back. The final tally was 1.8 million for Buchanan to 1.3 million for Frémont.

Historiography often depicts John as a glory- seeking fraud and Jessie as a manipulative and overly ambitious shrew. In fact, both were complicated figures far ahead of their time.

John, a Renaissance man with European manners—soft-spoken, laconic and contemplative—has been portrayed alternately by critics as a self-absorbed dilettante, an incompetent, a philanderer, a scoundrel and a glory-seeking egomaniac. Instead, the evidence suggests a painfully shy scientist, romantic by nature, introverted to the point of reclusive, sensitive to the point of melancholic and trusting to the point of naive.

Frémont’s worst crime, Benton once said, was daring to distinguish himself without graduating from West Point. By 1833 he had reached the top of his class at the select College of Charleston and had received a coveted assignment to teach navigational mathematics to Navy midshipmen. At 24 Frémont was personally selected by the secretary of war to participate in an Army reconnaissance survey, and at 25 he earned appointment to the elite topographical corps of 36 officers. One of the brightest stars in America’s highbrow field of exploration, he was the first to apply scientific methodology to a region dismissed by earlier explorers as uninhabitable, doing so with admirable conscientiousness and precision.

Jessie was, unquestionably, a political animal. Yet as shrewd and ambitious, brilliant and idealistic as she was, her life and fortune were dictated by the era in which she lived. Viewed historically as the wife of a gifted adventurer and daughter of a shrewd politician, Jessie was in fact an indomitable political force in her own right, boasting mental acuity, emotional toughness and political confidence more commonly associated with the “stronger sex.” What’s more, during the Civil War, she earned the nickname “General Jessie” for her advisory role when John became Union commander of the Western Department. Evolving from the role of privileged senator’s daughter to wife and mother, she eventually rose to the position of military and political strategist and national best-selling author. She attained these accomplishments not through John as her surrogate, but with John as her equal.

The Frémonts had a true peer marriage—unthinkable for the 19th century. Allegations of philandering arose during the vicious 1856 presidential campaign, but no convincing substantiation exists that either Jessie or John was unfaithful to the other. What the evidence indicates is that regardless of the nuances of their marriage, they were devoted to each other for 50 years (John died in 1890, Jessie in 1902), and that devotion was based on mutual love and admiration— a connection jealous contemporaries found threatening.

For decades the Frémonts struggled to operate within the bounds of convention and conformity while wrestling with the major events of their time—the exploration of the West, Mexican War, Gold Rush, birth of the Republican Party and, ultimately, the Civil War. At a moment when the nation was defining itself for the next century and a half, John and Jessie shared a quixotic political and ideological vision of what America should be. Through all the disappointment and failure—some of their own making, some at the hands of fate—they remained steadfast in their commitment to one another and to their country.

Sally Denton is the author of Faith and Betrayal; American Massacre; The Bluegrass Conspiracy; and The Money and the Power, with Roger Morris. Her 2007 book Passion and Principle: John and Jessie Frémont, the Couple Whose Power, Politics and Love Shaped Nineteenth-Century America is recommended for further reading. Denton is interviewed in this issue.

Originally published in the December 2008 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.