AT THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR II, the commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine, Admiral Erich Raeder, penned a despairing note in the navy’s war diary:

Today the war against England and France broke out….It is self-evident that the navy is in no manner sufficiently equipped in the fall of 1939 to embark on a great struggle with England. It is true in the short time since 1935…we have created a well-trained force which at the present time has 26 boats [submarines] capable of use in the Atlantic, but which is, nevertheless, much too weak to be decisive in war. Surface forces, however, are still too few in numbers and strength compared to the English fleet….[They] can only show that they know how to die with honor and thus, create the basis for the re-creation of a future fleet.

Raeder’s prediction was to prove close to the mark, except in his pious hope that the German navy’s destruction would lead to the creation of another, better fleet.

After the Second World War many historians gave the Germans high marks for their conduct of the war in the Atlantic. In retrospect, such judgments were too favorable. Little in that record suggests operational or strategic competence. As the greatest historian of the conflict, Gerhard Weinberg, has suggested, the Germans would have been better off in World War II if they had built no navy at all and devoted those resources to the army and the Luftwaffe.

Four days after taking office as chancellor in January 1933, Adolf Hitler announced to the Reich’s military leaders his goal of overthrowing the entire European balance of power. At the same time, he presented his military with a blank check to begin a massive program of rearmament. The Kriegsmarine’s leaders then embarked on a buildup that paid little attention to the Reich’s economic weaknesses or its geographic difficulties in any conflict with the British. They displayed even less imagination in their planning. Their emphasis throughout the 1930s was on the creation of a large fleet of battleships and heavy cruisers. Moreover, Raeder showed little interest in aircraft carriers, which he characterized as “only gasoline tankers.”

The first major naval operation of the war came with the German invasion of Scandinavia in April 1940. That amphibious operation succeeded in conquering Denmark and Norway but at a very high cost—which would have been even higher had the British been paying attention. One young British military analyst, Harry Hinsley, still without his Cambridge undergraduate degree, had warned his superiors that based on his analysis of the call signs of the Kriegsmarine’s warships, the Germans appeared to be on the brink of launching a major operation somewhere in Scandinavia. He was ignored, and the Germans slipped their landing forces into major Norwegian ports under the nose of the Royal Navy.

In early June 1940 Hinsley warned his superiors that the German battle cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst appeared to be operating off Norway’s North Cape. Again his superiors paid him no attention. The Germans promptly sank the British carrier Glorious with its entire complement of Hurricanes and pilots, plus two escorting destroyers. But on their run back to German harbors the two battle cruisers were torpedoed and heavily damaged by the British and were not available for active operations until December 1940. The German naval staff had risked sending the cruisers to the North Cape in a demonstration to influence “postwar budget debates”—despite Hitler’s warning to Raeder that it might be necessary to invade Britain at the end of the summer. So just when the Germans were considering the seaborne invasion of the British Isles, the Kriegsmarine had only one operational heavy cruiser and a small number of destroyers.

The performance of the Kriegsmarine’s surface fleet during the remainder of the war can be briefly summarized: The Gneisenau and the Scharnhorst were fully operational by January 1941 and returned to active service. They joined the cruiser Admiral Hipper in raiding Britain’s North Atlantic SLOCs—sea lines of communications—and all three raiders achieved some success in forcing the British to send battleships to guard the convoys. After sinking 115,000 tons of merchant shipping, the two battle cruisers reached Brest at the end of March 1941. Then, with the Scharnhorst in dry dock for overhaul, a British Coastal Command aircraft torpedoed the Gneisenau.

In May 1941 Raeder sent the new super battleship Bismarck, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, into the Atlantic. After sinking the British battle cruiser Hood, the Bismarck was attacked by a Swordfish aircraft launched from HMS Ark Royal, the kind of carrier Raeder had contemptuously dismissed. One torpedo jammed the Bismarck’s rudder, leaving the battleship able to do no more than travel in great circles in the mid-Atlantic. The Bismarck’s crew could only await their doom, which soon arrived with the battleships of the Home Fleet.

In the Battle of the Barents Sea in late December 1942, the performance of the pocket battleship Lützow and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper was so appallingly bad—they sank one destroyer out of a convoy protected by six destroyers and two corvettes—that Hitler ordered the navy to decommission and break up the surface fleet. Admiral Karl Dönitz, who replaced Raeder as the Kriegsmarine’s commander in chief, persuaded the führer to rescind his order, but the surface ships contributed little else to the war effort. A fleet led by the British battleship Duke of York sank the Scharnhorst off North Cape in late December 1943, while the Bismarck’s sister ship, the Tirpitz, was sunk in November 1944 in a Norwegian fjord by three 12,000-pound Tallboy bombs dropped by Bomber Command Lancasters. It was hardly the end with honor for the surface fleet that Raeder had imagined.

THUS, A NAVAL WAR AGAINST BRITAIN rested on what the German U-boats could achieve. Germany had gone to war in September 1939 with 57 U-boats, but only 26 of them were long-distance oceangoing boats. The exceedingly well-trained force was under Dönitz, an experienced submarine commander from the First World War. He drew his lessons from that conflict, and unlike most of his fellow admirals, believed that U-boats could wage a successful campaign against the British SLOCs. How he prepared for that conflict and conducted the Battle of the Atlantic shows his limitations as a military leader. Dönitz was a tactician with little interest in the potential of technology to extend the reach and impact of his offensive. A straight numbers man, he believed the crucial measure in a war against British commerce should be the tonnage of merchant ships sunk by U-boats. He also believed that, as in World War I, most of the fighting would take place in the waters close to the British Isles. A central land-based command headquarters would control the boats and concentrate them against British convoys, which Dönitz thought would be easy to find.

In the prewar period the Germans failed to do the kind of serious wargaming that the United States had carried out at the Naval War College. Such gaming could have indicated some of the operational difficulties the Germans might, and did, confront in their attacks on the British SLOCs. In particular, it likely would have suggested that the British response to any significant U-boat success would be to increase their antisubmarine forces and their capabilities—which might well make the waters around the British Isles too dangerous for U-boats. Thus, the campaign to interdict the SLOCs would almost inevitably have to move out into the open Atlantic, where the convoys would have more room to maneuver and where it would be difficult to concentrate the U-boat “wolf pack” group attacks on which Dönitz’s concept depended. It would also make intelligence a major factor in the fight.

The design of the U-boats the Germans built before and during the war underscores the narrowness of Dönitz’s vision. His emphasis was on the Type VII, a small 626-to-965-ton U-boat with a relatively short range. It was designed for use in the waters off the British Isles but would be at increasing disadvantage the farther out in the Atlantic it operated; it barely had the range to reach the east coast of the United States and fight there. The Type IX U-boat, a larger fleet submarine analogous to but smaller than the U.S. Navy’s fleet boats, had the range to operate along the east coast of the United States for significant periods of time. The fact that the Germans built nearly three times as many Type VIIs as Type IXs and continued to produce Type VIIs throughout the war underlines Dönitz’s lack of strategic imagination.

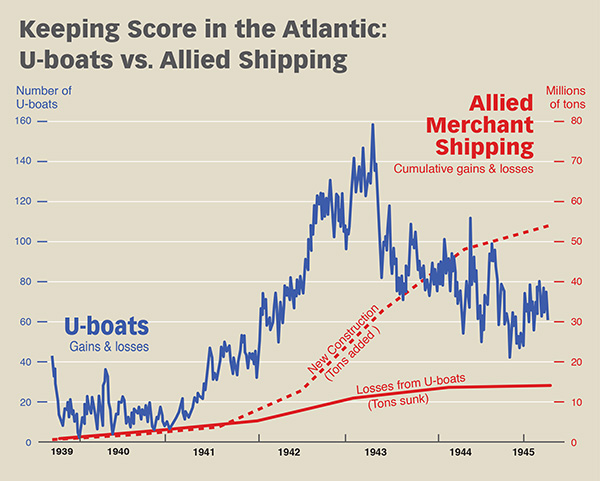

The German U-boat war did not get off to an impressive start. Only 35 new boats entered service in the war’s first year, while the Germans lost 28 at sea. However, the fall of France in spring 1940 changed the parameters within which the Battle of the Atlantic would be fought. German U-boats now had access to the major French naval ports of Brest, Saint-Nazaire, Bordeaux, and Cherbourg, which were closer to the mid-Atlantic than many British ports. The challenge of fighting off the German submarine menace was made more difficult for the Royal Navy by the threat of a cross-Channel invasion during the summer and fall of 1940. The British had to concentrate substantial numbers of destroyers at both ends of the Channel, approximately 35 at Harwich and 35 in the Plymouth and Portsmouth areas. That reduced the availability of antisubmarine escorts to protect the SLOCs, and the British paid a high price in lost ships and merchant sailors.

The Germans called fall and early winter 1940 the “first happy time,” as U-boat aces such as Günther Prien, Otto Kretschmer, and Joachim Schepke participated in the slaughter of the weakly protected British convoys. Attacks on convoys in September and October heralded the arrival of German wolf packs. In September 1940 four boats attacked convoy HX 72 out of Halifax and sank 11 of the 42 merchant vessels. Similar disasters followed, and Luftwaffe crews flying the ill-suited Fw-200C Condors sank over 300,000 tons of British shipping in 1940–1941.

But the British rapidly awoke to the danger. Many destroyers returned to convoy duty in the winter, while the Royal Navy focused on using technology to improve its antisubmarine capabilities. Some of these developments had long-term impacts and over time that became more important than immediate tactical advantages. The British pushed the envelope of antisubmarine warfare: developing and equipping the escorts with radar; improving ASDIC (the British equivalent of sonar); developing and equipping Coastal Command’s aircraft with airborne radar; improving the shore-based, direction-finding equipment to locate U-boats that were transmitting; developing direction-finding equipment to identify the positions of U-boats shadowing their convoys; and improving the power and killing potential of depth charges. They also developed new weapons such as the Hedgehog, a forward-firing mortar that was designed to launch salvos on U-boats that had just dived and were still at shallow depth, and the short-range radio, which allowed escorts to communicate among themselves without alerting German listening stations and giving away the convoy’s location. They also reintroduced the high-powered Leigh light, which, along with airborne radar, proved particularly deadly later in the war in night operations against U-boats. Though it would take considerable time for the British to man and equip their escorts’ crews and train them to use these weapons and gear, by early spring 1941 the British were well on the way to developing the technologies and weapons systems that would finally crush the U-boat threat. Significantly, the Germans displayed no such interest in improving the technologies available to their U-boats.

SOME IMPROVEMENTS IN ESCORTS and antisubmarine tactics had immediate impacts. In March 1941 the British sank five U-boats, including those commanded by veteran submariners Prien, Schepke, and Kretschmer—thanks in part to the new and highly effective Type 271 radar. Moreover, the increased number of escorts and air cover resulted in less success for U-boats around the British Isles. Nevertheless, the tonnage of merchant ships sunk remained high during the first six months of 1941. In March and April U-boats sank nearly half a million tons of Allied shipping. In May the total was over 320,000 tons; in June, some 302,000 tons. Winston Churchill noted in his memoirs that only the Battle of the Atlantic gave him sleepless nights during the war.

March also saw some crucial pieces of luck and some insight that provided the British with a major intelligence coup. Bletchley Park, the center of British code-breaking efforts, had had little success cracking the naval ciphers of the Enigma machine used by Dönitz’s U-boats. But in March 1941 Harry Hinsley had a brilliant insight: He suddenly remembered that German weather ships operating off Iceland were carrying Enigma machines and codebooks and suggested to his superiors that the Royal Navy mount a cutting-out operation to capture a weather ship containing the priceless daily settings for the Enigma U-boat coding. This time they listened, and the Home Fleet mounted an operation with three cruisers and four destroyers that was entirely successful. It was one of several Royal Navy successes in seizing Enigma settings and codebooks.

The British soon were able to break into the traffic between Dönitz’s headquarters in Lorient and the U-boats deployed to find British convoys. British code breaking—signals intelligence known as Ultra—grew so sophisticated that once Bletchley Park’s code breakers had cracked the U-boat code, they were able to continue decoding German radio traffic even without access to the enemy’s latest settings.

For the last half of 1941 Western Approaches Command, responsible for the Battle of the Atlantic, was able to guide the convoys, with Ultra’s help, around the U-boat patrol lines Dönitz had established. What happened to convoy HX 133 at the end of June 1941 underlines the Ultra contribution. U-203 had sighted the convoy and reported it to U-boat headquarters, which ordered a concentration of U-boats against the convoy. Bletchley Park decrypted those messages and warned Western Approaches Command, which immediately diverted the convoy and pulled escorts from two other convoys not under threat, sending them to reinforce HX 133. Coastal Command also concentrated its aircraft as the convoy came within range. After a five-day running battle, Dönitz gave up; he had lost two boats, while a major concentration of his submarines had managed to sink only six merchantmen.

In July 1941, the first month in which the British could incorporate Ultra intelligence fully into their operations at sea, losses to U-boats dropped to 61,676 tons, the lowest since May 1940. Losses spiked in September (292,829) and October (156,554), but that was largely a result of the Gibraltar convoys passing too close to German reconnaissance aircraft flying out of southern France—it was simply impossible to find room to maneuver the convoys around the U-boats in the vicinity of the straits.

THE REAL WARNING SIGN of how tenuous the framework of Dönitz’s U-boat offensive had become arrived at the end of 1941. Responding to the excessive losses on the British Gibraltar convoys in September and October, the Admiralty had shut down those convoys until December, when they could gather sufficient experienced escorts to protect a large convoy from Gibraltar through to the British Isles. In command of the 17 escorts was Captain Johnnie Walker, the most effective and fiercest antisubmarine officer in the war. Joining Walker’s escorts was Britain’s first escort carrier, the Audacity. Warned by Ultra where the U-boats were located, Walker led the convoy on a route well to the south before turning north. It took the German U-boats and aircraft two days to find the convoy. On the third day, the Audacity’s aircraft caught U-131 on the surface, and after their attack forced it to dive, the escorts finished it off. The next morning Walker’s escorts caught U-434 and sank it. That night U-574 torpedoed a destroyer, the Stanley, but Walker’s ship blasted the sub to the surface with depth charges; then the sloop Stork rammed and sank it. The following night the escorts sank U-567. The British did lose the Audacity, but that was because its commander failed to heed Walker’s advice and each evening took the carrier outside the convoy, where it was eventually torpedoed by U-471.

After losing four U-boats, and with the rest constantly harried by the escorts, Dönitz called off the attack. The British had lost only two merchantmen and a destroyer in addition to the escort carrier; the Germans lost four U-boats, with several others damaged. The warning was plain to Dönitz: A well-escorted convoy with good leadership was now able to impose unacceptable casualties on the wolf packs.

The battle’s focus then underwent a drastic change in venue: On December 11, 1941, Hitler declared war on the United States, an egregious strategic mistake if ever there was one. The Kriegsmarine’s leadership was delighted. In fact, Raeder and Dönitz had visited the führer twice the previous summer in an effort to persuade him to do just that, since it would allow them to launch their U-boats against shipping along America’s east coast. Hitler had initially put them off on the basis that the time was not yet right. But in the second week of December, the German admirals got their wish. The Americans were completely unprepared for submarine attacks, and the result was a slaughter of unescorted vessels—unescorted because Adolphus Andrews, the admiral in charge of antisubmarine defenses, had not a clue. The losses were terrible, and they mounted steadily as Dönitz concentrated his Type IXs on America’s east coast and then into the Caribbean. Merchant shipping losses in those waters rapidly rose from 276,795 tons (59 ships) in January 1942 to 534,064 tons (95 ships) in March. Not only was the American tactical approach faulty but Tenth Fleet inexplicably refused to incorporate British or American intelligence into its operations. The real problem was that the Allies had to defend a vastly increased area from the depredations of the U-boats. The SLOCs requiring protection ranged from Murmansk to the British Isles and from the east coast of North America to the United Kingdom.

IN EARLY 1942 THE AMERICANS finally introduced convoys and increased air patrols, and the U-boats moved on to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, which still lacked effective defenses. In May sinkings of Allied shipping there reached almost half a million tons, with losses particularly heavy among tankers. All told, German U-boats sank three million tons in U.S. waters in the first half of 1942. During that same period, air and surface antisubmarine forces managed to sink only six U-boats. Dönitz thought he was on the brink of victory. He was not. The Americans, at last awake to the danger, concentrated on establishing effective air and escort forces to battle the U-boats in the Gulf and Caribbean. By July the number of sinkings in those waters had dropped by a third, while the Germans lost eight boats there.

IN EARLY 1942 THE AMERICANS finally introduced convoys and increased air patrols, and the U-boats moved on to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, which still lacked effective defenses. In May sinkings of Allied shipping there reached almost half a million tons, with losses particularly heavy among tankers. All told, German U-boats sank three million tons in U.S. waters in the first half of 1942. During that same period, air and surface antisubmarine forces managed to sink only six U-boats. Dönitz thought he was on the brink of victory. He was not. The Americans, at last awake to the danger, concentrated on establishing effective air and escort forces to battle the U-boats in the Gulf and Caribbean. By July the number of sinkings in those waters had dropped by a third, while the Germans lost eight boats there.

Ironically, had the Battle of the Atlantic not moved to the east coast of the United States, the Germans would soon have realized that the British had broken Enigma in late 1941. But even without that awareness, Germany introduced a new rotor to the naval Enigma machine in February 1942, adding another layer of complexity, and for the next year the British were unable to break back in.

Nonetheless, the Americans gained ground in the Battle of the Atlantic. From a dismal total of only 21 U-boats sunk in the first half of 1942, they managed to take out 65 over the last half of the year. The heavy losses in merchant vessels also led the U.S. government to embark on a major program of building replacement merchant vessels, an effort that would lead to the mass production of Liberty ships. That unprecedented production would eventually replace the losses of the war’s first years and provide support for the projection of American power across the Atlantic and Pacific.

A NEW CHALLENGE confronting the Allied navies—the Royal Navy, the U.S. Navy, and the Royal Canadian Navy—was that German production and crewing up of U-boats had increased significantly. During the final six months of 1942, Dönitz received approximately 30 new U-boats every month, though few technological upgrades had been made to them; their lack of radar made it difficult to identify and follow convoys or to attack at night. To Dönitz, the U-boat war continued to be a matter of tactics, not technology. Moreover, the new boats masked the fact that raw numbers could not make up for the steady decline in the level of training and experience of U-boat skippers. U-boat successes had been largely the work of a handful of bold and experienced commanders; the commanders of the new boats proved incapable of attacking convoys effectively.

Though the Germans had broken the Allied code for convoys, Western Approaches Command was able to guide over 60 percent of the convoys across the Atlantic without loss. That was thanks to shore-based direction-finding gear that pinpointed U-boat transmissions (the U-boat high command and the boats continued to exchange a needlessly high number of transmissions). In the last half of 1942, as the Americans tightened up their antisubmarine defenses in the Caribbean, the Germans moved their U-boats back into the central area of the North Atlantic, where Allied air power was still unable to fully cover the convoys.

The increases in the number of U-boats allowed Dönitz to extend his patrol lines in the Atlantic and, with the help of his code breakers, to target a number of convoys. October and November 1942 were disasters for the Allies. When a large number of escorts were pulled off convoy duty to protect Operation Torch, the landings in North Africa, the Germans again savaged the shipping in the SLOCs. October’s total was 105 ships sunk, 566,939 tons, and in November the U-boats achieved their highest total of the war: 123 ships, 768,732 tons. Then the Atlantic blew up a series of storms that severely limited the ability of the U-boats to operate in December 1942 and January 1943.

The Battle of the North Atlantic resumed in full fury in February 1943, but by then the British had again broken the German naval codes. The issue became which side would make the mistake of transmitting an indication that they had broken the other’s codes. The British, with their emphasis on security, did not give the game away; the Germans did. And once the British saw evidence that the Germans were reading their convoy codes, they immediately embarked on the herculean task of redoing their codes.

With Dönitz concentrating masses of U-boats in the central Atlantic and with the weather finally calming down—at least in the North Atlantic—fierce battles broke out as the British moved their convoys across the mid-ocean gap in air cover. In February the Allies lost 359,276 tons in the North Atlantic; still with 18 U-boats lost, Dönitz could not have been happy. In March sinkings by U-boats reached 627,377 tons, but within two months Allied escorts and air cover reversed the battle. The Germans lost 41 boats in May while sinking only 264,852 tons of shipping in the North Atlantic. The losses were so heavy that Dönitz finally had to call off the campaign.

The U-boat war had reached the tipping point, one that the Germans should have foreseen. But with the Germans literally fighting day to day, with no longer-range perspective, they continued to place tactics and numbers before all else. In effect, they continued to fight the war with a slightly improved version of their World War I boat (their technological improvements came too late in the war to make much difference), and with tactics that were increasingly ineffective. The British on the other hand utilized their intellectual and military-experience capital to create a superb defense, in which tactics played only a partial role.

Fanatical to the end, Dönitz continued to send his U-boat teams out in their obsolete craft against impossible odds. Despite moving their boats away from the North Atlantic after the disastrous losses of May 1943, the Germans lost 143 over the rest of the year. In 1944 they would lose 249 boats and in the five months of 1945 another 159; in the last year of the war they were losing close to one U-boat for every two merchantmen they sank. Nearly 30,000 U-boat sailors would die in pursuing Dönitz’s flawed hope that somehow fanaticism and faith in the führer would lead to success. Throughout the war, the Germans failed to recognize how effectively their opponents were using technology to counteract the U-boat attacks. Part of this was the result of inadequate staffing and analysis, but part was due to Dönitz’s decision to move his boats from one theater to another as the Allies adapted. Seeking the weak link in the Allied system of shipping, the Germans eventually faced a situation when the Allied defenses were strong everywhere. Then, without making any real changes in their own technological and tactical effectiveness, their U-boats were quite literally sunk.

Williamson Murray has taught military and diplomatic history at Yale, Ohio State, all three U.S. military war colleges, West Point, and Annapolis. He is the author of numerous books on war and strategy, including Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present (May 2014).