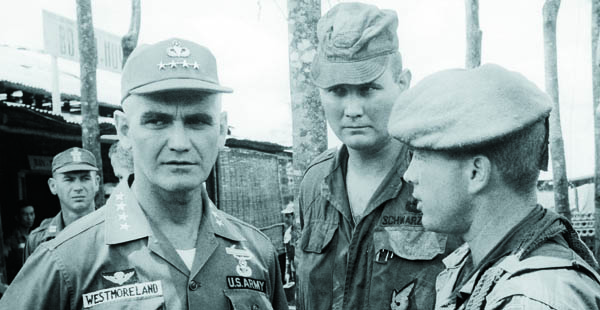

General William Westmoreland’s words to Major Norman Schwarzkopf left a lasting impression at Duc Co in 1965

Soldiers often form a strong opinion toward the news media, either positive or negative, from a first encounter. In August 1965, I may have been the unwitting influence on a U.S. Army officer in Vietnam who would go on to become the commanding officer of U.S. forces in the first Gulf War, General H. Norman Schwarzkopf.

Major Schwarzkopf was an adviser to the South Vietnamese Airborne who were attempting to secure Duc Co, a strategic U.S. Special Forces camp west of Pleiku near the Cambodian border. The South Vietnamese forces had been holding off two full regiments of North Vietnamese regulars, a much larger and much better trained and equipped enemy than the two Viet Cong battalions they had expected to fight there.

As a freelancer, just a few months in-country, I hitched a ride into the raging battle with a U.S. Army “dustoff” chopper going in to recover Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) casualties. It would be my baptism of fire in Vietnam.

In several days of heavy and costly fighting, the South Vietnamese marines and ARVN managed to push the Communist troops back to their sanctuaries in Cambodia. I had been covering the ARVN forces for most of the battle until the siege of Duc Co was lifted on August 17.

The following morning Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) commander General William Westmoreland, dressed in freshly pressed fatigues and shined boots, arrived by helicopter to personally review the success of an important engagement.

He was introduced to the senior U.S. adviser to the victorious South Vietnamese troops, ostensibly to gather his observations and be briefed on the performance of our allies.

While my coverage of Duc Co—both the stills and film footage I shot—got wide exposure and turned out to be my first of many exclusives in Vietnam, I had long forgotten about the young major who Westmoreland met with there. It wasn’t until I read General Schwarzkopf’s 1992 autobiography and his account of the battle for Duc Co, that I recalled taking those photos of Westmoreland and his meeting with American advisers there.

And, according to Schwarzkopf in It Doesn’t Take a Hero, what transpired was a most peculiar and somewhat disturbing encounter with the astute and esteemed General Westmoreland, one that stuck with him, and left a lasting negative impression. Schwarzkopf, while never identifying Westmoreland by name in his account, describes the encounter:

The General came over and recoiled a little because I hadn’t had a change of clothes in a week and had been handling bodies and stank. Meanwhile the camaramen had followed and several reporters came up with microphones. “No, no,” the General said. “Please get the microphones out of here. I want to talk to this man.” I’m not sure what I expected him to say. Maybe something like, “Are your men all right? How many people did you lose?” or “Good job—we’re proud of you.” Instead there was an awkward silence, and then he asked, “How’s the chow been?”

The chow? For chrissakes, I’d been eating rice and salt and raw jungle turnips that Sergeant Hung had risked his life to get! I was so stunned that all I could say was, “Uh, fine sir.”

“Have you been getting your mail regularly,” inquired the General.

All my mail had been going to my headquarters in Saigon and I assumed it was okay. So I said, “Oh yes Sir.”

“Good, fine job, lad.” Lad? And with that he walked off. It was an obvious PR stunt. He’d waved off the microphones, but the cameras were still whirring away. At that moment I lost any respect I’d ever had for that general.

While this was happening, from a distance I took a number of photos and cranked off a couple of minutes of TV film of Westy, seemingly having an earnest conversation with the big American major in his torn and muddy fatigues.

In his book, Schwarzkopf then goes on to describe how his mother watched my TV footage on the evening news the next night—and what her reaction was:

The next night, back in New Jersey, the local TV station called my mother and told her that her son was going to be on the evening news. She watched the report, and until the day she died, she always spoke glowingly of the wonderful general she’d seen talking to her son in Vietnam and bucking up his morale.

In 1983 Maj. Gen. Schwarzkopf was senior adviser to the U.S. Joint Task Force in the invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada. It was the first time in American history that journalists were barred from going in with our troops. Seven years later, in the 1990-91 Gulf War, as commander of the Coalition Forces, General Schwarzkopf laid down the most draconian restrictions against press coverage since World War I. Thus, the greatest armored assault since El Alamein, when American forces pushed into Iraq, did not have a single television crew to document it.

Since putting the pieces of this story together, I have often wondered if my report on Schwarzkopf’s strange briefing with General Westmoreland at Duc Co—that his mother so misinterpreted—may have soured him forever on having reporters at the front lines.

Don North spent more than four years in Vietnam as a freelance photographer and correspondent for ABC and NBC News. He is a frequent contributor to Vietnam and VietnamMag.com.