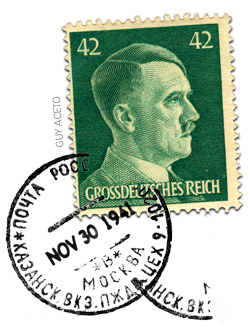

One of the classic “what ifs” of the Second World War centers on how—or if—the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, code-named Operation Barbarossa, could have achieved a quick victory. Hitler certainly believed that it could. All one had to do, he insisted, was to “kick in the door” and the “whole rotten structure” of Stalin’s Communist regime would come tumbling down. In many respects, Barbarossa was a stunning success. The Germans took the Soviets completely by surprise, advanced hundreds of miles in just a few weeks, killed or captured several million Soviet troops, and seized an area containing 40 percent of the USSR’s population, as well as most of its coal, iron ore, aluminum, and armaments industry. But Barbarossa failed to take its capstone objective, Moscow. What went wrong?

One of the classic “what ifs” of the Second World War centers on how—or if—the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, code-named Operation Barbarossa, could have achieved a quick victory. Hitler certainly believed that it could. All one had to do, he insisted, was to “kick in the door” and the “whole rotten structure” of Stalin’s Communist regime would come tumbling down. In many respects, Barbarossa was a stunning success. The Germans took the Soviets completely by surprise, advanced hundreds of miles in just a few weeks, killed or captured several million Soviet troops, and seized an area containing 40 percent of the USSR’s population, as well as most of its coal, iron ore, aluminum, and armaments industry. But Barbarossa failed to take its capstone objective, Moscow. What went wrong?

Some historians have pointed to the German decision to advance along three axes: in the north toward Leningrad, in the south toward Ukraine, and in the center against Moscow. But the Wehrmacht had force enough to support three offensives, and its quick destruction of so many Soviet armies suggests that this was a reasonable decision. Others have pointed to Hitler’s decision in August to divert most of the armored units attached to Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group Center, whose objective was Moscow, and send them south to support an effort to surround and capture the Soviet armies around Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. The elimination of the Kiev pocket on September 26 bagged 665,000 men, more than 3,000 artillery pieces, and almost 900 tanks. But it delayed the resumption of major operations against Moscow until early autumn. This, many historians argue, was a fatal blunder.

Yet, as historian David M. Glantz points out, such a scenario ignores what the Soviet armies around Kiev might have done had they not been trapped, and introduces too many variables to make for a good counterfactual. The best “minimal rewrite” of history must therefore focus on the final German bid to seize Moscow, an offensive known as Operation Typhoon.

Here is how Typhoon might have played out:

When the operation begins, Army Group Center enjoys a substantial advantage over the Soviet forces assigned to defend Moscow. It has at its disposal 1.9 million men, 48,000 artillery pieces, 1,400 aircraft, and 1,000 tanks. In contrast, the Soviets have only 1.25 million men (many with little or no combat experience), 7,600 artillery pieces, 600 aircraft, and almost 1,000 tanks. The seeming parity in the number of tanks is misleading, however, since the overwhelming majority of Soviet tanks are obsolescent models.

Initially, Army Group Center runs roughshod over its opponents. Within a few days, it achieves the spectacular encirclement of 685,000 Soviet troops near the towns of Bryansk and Vyazma, about 100 miles west of Moscow. The hapless Russians look to the skies for the onset of rain, for this is the season of the rasputitsa—literally the “time without roads”—when heavy rainfall turns the fields and unpaved roads into muddy quagmires. But this year the weather fails to rescue them, and by early November frost has so hardened the ground that German mobility is assured. With Herculean efforts from German supply units, Army Group Center continues to lunge directly for Moscow.

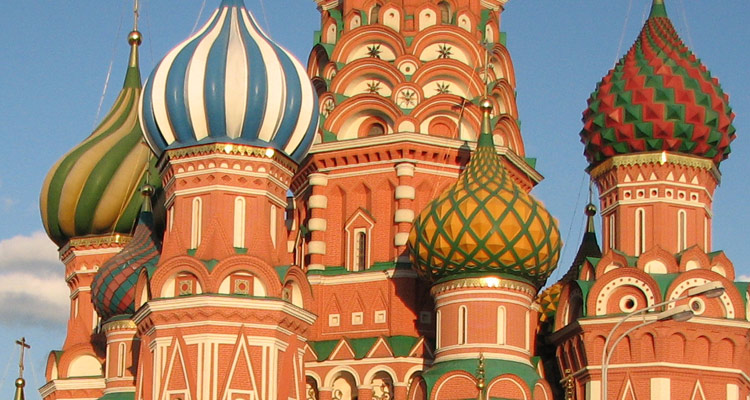

Thoroughly alarmed, the Stalin regime evacuates the government 420 miles east to Kuybyshev, north of the Caspian Sea. It also evacuates a million Moscow inhabitants, prepares to dynamite the Kremlin rather than have it fall into German hands, and makes plans to remove Lenin’s tomb to a safe place. Stalin alone remains in Moscow until mid-November, when the first German troops reach the city in force. And in obedience to Hitler’s order, Fedor von Bock uses Army Group Center to surround Moscow, instead of fighting for the city street by street. Nonetheless, the Soviet troops withdraw rather than fall prey to yet another disastrous encirclement, and on November 30—precisely two months after Operation Typhoon begins—it culminates in the capture of Moscow.

The above scenario is historically correct in many respects. The three major departures are the absence of the rasputitsa, which did indeed bog down the German offensive for two crucial weeks; the headlong drive toward Moscow rather than the diversion of units to lesser objectives in the wake of the victory at Bryansk and Vyazma—a major error; and, of course, the capture of Moscow itself.

But would the fall of Moscow have meant the defeat of the Soviet Union? Almost certainly not. In 1941 the Soviet Union endured the capture of numerous major cities, a huge percentage of crucial raw materials, and the loss of four million troops. Yet it still continued to fight. It had a vast and growing industrial base east of the Ural Mountains, well out of reach of German forces. And in Joseph Stalin it had one of the most ruthless leaders in world history—a man utterly unlikely to throw in the towel because of the loss of any city, no matter how prestigious.

A scenario involving Moscow’s fall also ignores the arrival of 18 divisions of troops from Siberia—fresh, well-trained, and equipped for winter fighting. They had been guarding against a possible Japanese invasion, but a Soviet spy reliably informed Stalin that Japan would turn southward, toward the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines, thereby freeing them to come to the Moscow front. Historically, the arrival of these troops took the Germans by surprise, and an unexpected Soviet counteroffensive in early December 1941 produced a major military crisis. Surprised and disturbed, Hitler’s field commanders urged a temporary retreat in order to consolidate the German defenses. But Hitler refused, instead ordering that German troops continue to hold their ground. Historically they managed to do so. However, with German forces extended as far as Moscow and pinned to the city’s defense, this probably would not have been possible. Ironically, for the Germans, the seeming triumph of Moscow’s capture might well have brought early disaster.