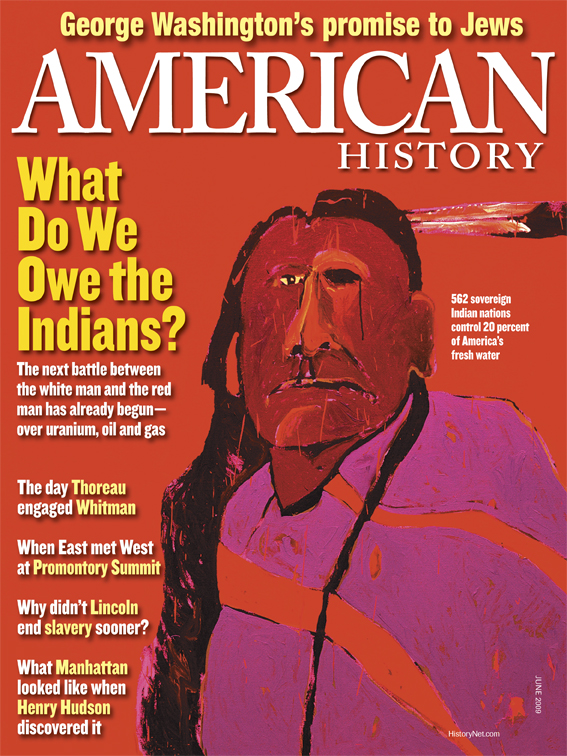

Images accompanying this article are from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian exhibition, “Fritz Scholder: Indian/Not Indian,” which is on display in Washington, D.C., through August 16 (www.americanindian.si.edu). All Images copyright Estate of Fritz Scholder.

The Yellowtail ranch, tucked into a narrow valley of soft-rock geology that separates the Big Horn Mountains from the surrounding plains on the southern border of Montana, is not the easiest place to find. Hang a right at Wyola, population 100, the home of the “Mighty Few” as Wyolians are known to their fellow Crow Indians, and head straight for the mountains. This is the rolling rangeland where Montana got its famous moniker, Big Sky Country. Eventually a red sandstone road will take you to a small log cabin on Lodge Grass Creek, 26 miles from the nearest telephone.

The Crow Indian Nation once stretched for hundreds of miles across this high plains grassland without a single road, fencepost or strand of barbed wire to mar the view. Then, in 1887, the federal government cast aside its treaty obligations to the Crow and other tribes and opened up their homelands to white settlers. Cattle soon replaced buffalo, and a hundred years later, about the same time the economics of the cattle industry began circling the drain, geologists discovered that the Big Horn Mountains are floating on a huge lake of crude oil. It wasn’t long before guys in blue suits and shiny black cars were cruising the back roads of Crow country and gobbling up land and mineral rights for pennies on the dollar. By hook and crook, the Yellowtails managed to keep their 7,000-acre chunk of that petrochemical dream puzzle. “We just barely hung on to this ranch in the ’80s,” says Bill Yellowtail, who, in addition to being a cattleman, has been a state legislator, a college professor, a fishing guide and a regional administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency. “It was dumb luck, I guess. And stubbornness.”

!["The American Indian." Fritz Scholder 1970. Oil on linen. Indian Arts and Crafts Board Collection, Department of the Interior, at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Photo by Walter Larrimore, NMAI. [Click to view larger image.]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2009/American%20History/fritz-scholder-flag-draped-indian-tbnl.jpg) At 6 feet 2 inches tall and 250 pounds, Yellowtail is a prepossessing figure, and no matter where his life mission takes him, his spirit will always inhabit this place. When his eyes take in the 360-degree view of soaring rock and jack-pine forest and endless blue sky, he sees a wintering valley of 10,000 bones that has been home to his clan for nearly a millenium. And because his inner senses were shaped by this land, by this scale of things, his vision of the future is a big picture. “The battle of the 21st century will be to save this planet,” he says, “and there’s no doubt in my mind that the battle will be fought by native people. For us it is a spiritual duty,” says Yellowtail, sweeping his hand across the thunderous silence of the surrounding plains from the top of a sandstone bluff, “and this is where we will meet.”

At 6 feet 2 inches tall and 250 pounds, Yellowtail is a prepossessing figure, and no matter where his life mission takes him, his spirit will always inhabit this place. When his eyes take in the 360-degree view of soaring rock and jack-pine forest and endless blue sky, he sees a wintering valley of 10,000 bones that has been home to his clan for nearly a millenium. And because his inner senses were shaped by this land, by this scale of things, his vision of the future is a big picture. “The battle of the 21st century will be to save this planet,” he says, “and there’s no doubt in my mind that the battle will be fought by native people. For us it is a spiritual duty,” says Yellowtail, sweeping his hand across the thunderous silence of the surrounding plains from the top of a sandstone bluff, “and this is where we will meet.”

What Yellowtail describes with the sweep of his hand is not so much a physical place as a metaphorical landscape where epic legal battles over the allocation and distribution of rapidly diminishing natural resources are destined to be fought. Tacitly, those looming battles echo a question that Americans have finessed, deflected or avoided answering ever since the colonial era: What do we owe the Indian? Long before the United States became an independent nation, European monarchs recognized the sovereignty of Indian nations. They made nation-to-nation treaties with many of the Eastern tribes, and our Founders, in turn, acknowledged the validity of these compacts in Article VI, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which describes treaties as “the supreme law of the land.” Once the Constitution was ratified, the new republic joined a pre-existing community of sovereign nations that already existed within its borders. Today, the United States recognizes 562 sovereign Indian nations, and much of what we owe them is written in the fine print of 371 treaties.

In 2009, Indians comprise about 1 percent of the population, and irony of ironies, the outback real estate they were forced to accept as their new homelands in the 19th century holds 40 percent of the nation’s coal reserves. And that’s just for openers. At a time when the nation’s industrial machinery and extractive industries are running out of critical mineral resources, Indian lands hold 65 percent of the nation’s uranium, untold ounces of gold, silver, cadmium, platinum and manganese, and billions of board feet of virgin timber. In the ground beneath that timber are billions of cubic feet of natural gas, millions of barrels of oil and a treasure chest of copper and zinc. Perhaps even more critically, Indian lands contain 20 percent of the nation’s fresh water.

Tribal councils are well aware of the treasures in the ground beneath their boots and are determined to protect them. Fifteen hundred miles southwest of Yellowtail Ranch, Fort Mojave tribe lawyers thwarted a government nuclear waste facility in Ward Valley, Calif. Eight hundred miles east of Ward Valley, Isleta Pueblo attorneys recently won a U.S. Supreme Court contest that forced the city of Albuquerque to spend $400 million to clean up the Rio Grande River. Northwest tribes won the right to half of the commercial salmon catch in their ancestral waterways, including the Columbia and Snake rivers. And, after a 20-year-long legal battle, the Potawatomi and Chippewa tribes of Wisconsin prevented the Exxon Corporation from opening a copper mine at Crandon Lake, a battle Indian lawyers won by enforcing Indian water rights and invoking provisions in the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Air Act.

The Indian Wars of the 19th century were largely fought over land because the federal government refused to uphold its various treaty obligations. The spoils in the 21st-century battles will be natural resources, and underlying those battles will be the familiar thorn of sovereignty. “Back in the old days,” says Tom Goldtooth, the national director for the Indigenous Environmental Network, “we used bows and arrows to protect our rights and our resources. That didn’t work out so well. Today we use science and the law. They work much better.”

None of our laws are more deeply anchored to our national origin than those that bind the fate of the Indian nations to the fate of the republic. And none of our Founding Fathers viewed the nation’s debt to the Indians with greater clarity than George Washington. “Indians being the prior occupants [of the continent] possess the right to the Soil,” he told Congress soon after he was elected president. “To dispossess them…would be a gross violation of the fundamental Laws of Nature and of that distributive Justice which is the glory of the nation.” In Washington’s opinion, the young war-depleted nation was in no condition to provoke wars with the Indians. Furthermore, he warned Congress that no harm could be done to Indian treaties without undermining the American house of democracy.

The country had no sooner pushed west over the Allegheny Mountains than problems began to emerge with the Constitution itself. The simple model of federalism envisioned by the Founders was proving unequal to the task of managing westward migration. Nothing in the Constitution explained how the new federal government and the states were going to share power with the hundreds of sovereign Indian nations within the republic’s borders. The Constitution’s commerce clause was designed to neutralize the jealousy of states by giving the federal government exclusive legal authority over treaties and commerce with the tribes, but when Georgia thumbed its nose at Cherokee sovereignty in 1802 by demanding that the entire nation be removed from its territory, the invisible fault line in federalism suddenly opened into a chasm.

The Indians found themselves entangled in a fierce jurisdictional battle that they had no part in starting. It was not their fight, but when the smoke and dust finally settled four decades later, the resolution would be paid for in Indian blood. Georgia’s scheme was to bring the issue of states’ rights to a national crisis point, and it worked. Bewailing the arrogance of “southern tyrants,” President John Quincy Adams declared that Georgia’s defiance of federal law had put “the Union in the most imminent danger of dissolution….The ship is about to founder.” Short of declaring war against Georgia and its sympathetic neighbors, the nation finally turned in desperation to the Supreme Court.

When the concept of Indian sovereignty was put to the test, Chief Justice John Marshall offered up a series of judgments that infuriated Southern states’ rights advocates, including his cousin and bitter rival Thomas Jefferson. In three landmark decisions, known as the Marshall Trilogy issued between 1823 and 1832, the court laid the groundwork for all subsequent federal Indian law. In Johnson v. McIntosh, Marshall affirmed that under the Constitution, Indian tribes are “domestically dependent nations” entitled to all the privileges of sovereignty with the exception of making treaties with foreign governments. He explained in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia that the federal government and the Indian nations are inextricably bound together as trustee to obligee, a concept now referred to as the federal trust doctrine. He also ruled that treaties are a granting of rights from the Indians to the federal government, not the other way around, and all rights not granted by the Indians are presumed to be reserved by the Indians. This came to be known as the reserved rights doctrine.

The federal trust doctrine and the reserved rights doctrine placed the government and the tribes in a legally binding partnership, leaving Congress and the courts with a practical problem—guaranteeing tribes that American society would expand across the continent in an orderly and lawful fashion. Inevitably, as disorderly and unlawful expansion became the norm—by common citizens, presidents, state legislators, governors and lawmakers alike—the conflict of interest embedded in federalism gradually eclipsed the rights of the tribes.

For their part, President Andrew Jackson and the state of Georgia scoffed at Marshall’s rulings and accelerated their plans to remove all Indians residing in the Southeast to Oklahoma Territory. Thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek and Chickasaw Indians died in forced marches from their homelands. Eyewitness reports from the “trail of tears” were so horrific that Congress called for an investigation. The inquiry—conducted by Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the grandson of his revolutionary era namesake—revealed a “cold-blooded, cynical disregard for human suffering and the destruction of human life.” Hitchcock’s final report, along with supporting evidence, was filed with President John Tyler’s secretary of war, John C. Spencer. When Congress demanded a copy, Spencer replied with a curt refusal: “The House should not have the report without my heart’s blood.” No trace of Hitchcock’s final report has ever been found.

By 1840 America’s first Indian “removal era” was completed, and within a decade a second removal era would begin. Massive land grabs in the West commenced when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, opening treaty-protected Indian lands to white settlement. While the act is most often remembered as a failed attempt to ease rapidly growing tensions between the North and South by giving settlers the right to determine whether to allow slavery in the new territories, it also embodied a brazen disregard by Washington lawmakers of their trust obligations to Western tribes.

Three decades later, the federal government ignored its trust obligations yet again when the 1887 Dawes Act gave the president the authority to partition tribal lands into allotments for individual Indian families. “Surplus” Indian land was opened up to settlement by white homesteaders, and soon 100 million acres of land once protected by treaties had been wrested from Indian control. Euphemistically known as the Allotments Era, this period lasted until 1934, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Congress finally put an end to the land grabs. Meanwhile, federal courts began relying on Marshall’s century-old legal precedents in a series of controversial decisions that forcefully reminded Washington lawmakers of their binding obligations to the tribes. The decisions also prompted jealous state governments to resume their adversarial relationship with tribes, and to treat the tribes’ partner, the federal government, as a heavy-handed interloper.

Although many Allotment Era executive orders were eventually ruled illegal by federal courts, the genie was out of the bottle. There was no way to return the land that had been taken to its rightful owners, and besides, the powerless remnants of once great Indian tribes were lucky to survive from one year to the next. Ironically, the turning point for Indians came decades later, courtesy of Richard Nixon.

On July 8, 1970, in the first major speech ever delivered by an American president on behalf of the American Indian, Nixon told Congress that federal Indian policy was a black mark on the nation’s character. “The American Indians have been oppressed and brutalized, deprived of their ancestral lands, and denied the opportunity to control their own destiny.” Through it all, said Nixon, who credited his high school football coach, a Cherokee, with teaching him lessons on the gridiron that gave him the fortitude to be president, “the story of the Indian is a record of endurance and survival, of adaptation and creativity in the face of overwhelming obstacles.”

In Nixon’s view, the paternalism of the federal government had turned into an “evil” that held the Indian down for 150 years. Henceforth, he said, federal Indian policy should “operate on the premise that Indian tribes are permanent, sovereign governmental institutions in this society.” With the assistance of Sen. James Abourezk of South Dakota, Nixon’s staff set about writing the American Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which gave tribes more direct control over federal programs that affected their members. By the time Congress got around to passing the law, in 1975, Nixon had left the White House in disgrace. But for the 1.5 million native citizens of the United States, the Nixon presidency was a great success that heralded an end to their “century-of-long-time-sleeping.”

Word of Nixon’s initiatives rumbled like summer thunder through the canyon lands and valleys of Indian Country. While the American Indian Movement grabbed national attention by staging a violent siege of the town of Wounded Knee, S.D., in 1973, thousands of young Indian men and women began attending colleges and universities for the first time. According to Carnegie Foundation records, in November 1968 fewer than 500 Indian students were enrolled in schools of higher education. Ten years later, that number had jumped tenfold.

Among the first to benefit from Nixon-era policies was a generation of determined young Indians with names like Bill Yellowtail, Tom Goldtooth and Raymond Cross. “For the first time in living history, Indian tribes began developing legal personalities,” says Cross, a Yale-educated Mandan attorney and law school professor who has made two successful trips to the U.S. Supreme Court to argue the merits of Indian sovereignty. “They realized that federal Indian policies had been a disaster for well over a hundred years. The time had come to change all that.”

As various tribes slowly developed their political power, young college educated Indians came to view efforts to wrest away their natural resources as extensions of 19th-century assaults on sovereignty and treaty rights. Mineral corporations, federal agencies and state governments—emboldened by 160 years of neglect of the government’s trust responsibilities—were accustomed to having their way with Indian Country.

In places like Lodge Grass, Shiprock and Mandaree, long-term neglect of treaty rights had translated into widespread poverty and a 70 percent unemployment rate. In New Town, Yankton and Second Mesa, that neglect meant a proliferation of kidney dialysis clinics and infant mortality rates that would be scandalous in Ghana. In Crow Agency, Lame Deer and Gallup, neglect looked like a whirlpool of dependency on booze and methamphetamines that spat Indian youth out into a night so dark that wet brain, self-inflicted gunshot wounds, cirrhotic livers and the all too familiar jalopy crashes, marked by a blizzard of little white crosses on wind-scoured reservation byways, read like a cure for living. Indians, no less than their counterparts in white society, found themselves prisoners of the pictures in their own heads.

Two hundred and thirty-one years after the new United States signed its first treaty with the Delaware Indians, there is too much money on the table, and too many resources in the ground, for either the Indians or the industrialized world to walk away from Indian Country without a fight. There may be occasional celebrations of mutual understanding and reconciliation, but no one is fooling anybody. The contest of wills will be just as fierce as it was in the Alleghenies in the 1790s, in Georgia in the 1820s, and on the Great Plains in the 1850s. “From the beginning, the Europeans’ Man versus Nature argument was a contrived dichotomy,” says Cross. “The minute you tame nature, you’ve destroyed the garden you idealized. The question that confronts the dominant society today is ‘Now what?’ After you destroy Eden, where do you go from here?”

Meanwhile, on a late Sunday evening inside a cabin on Lodge Grass Creek at Yellowtail Ranch, the weighty matters of the world are at bay. Friends and family have gathered around a half moon table in the kitchen for an evening of community fellowship. No radio. No cell phones. Wide-eyed children lie curled like punctuation marks under star quilts in the living room, listening to grown-ups absorbing each other’s lives. Mostly, the grown-ups dream out loud over cherry pie and homemade strawberry ice cream. Gallons of coffee flow from a blue speckled pot on the stove. At peak moments all seven voices soar and collide in clouds of laughter.

Outside, the Milky Way glows overhead as brightly as a Christmas ribbon. The surrounding countryside is held by a silence so pure, so absolute, that individual stars seem to sizzle. Laughter, happy voices and a shriek of disbelief drift into the night where far overhead a jet’s turbines pull at the primordial silence with a whisper. From 35,000 feet in the night sky, soaring toward tomorrow near the speed of sound, a transcontinental traveler glances out his window and sees a single light burning in an ocean of darkness. He wonders: Who lives down there? Who are those people? What are their lives like?

Far below, that light marks the spot where the Indians’ future meets the Indians’ past, where the enduring ethics of self-sufficiency and interdependence, cooperation and decency, community and spirit are held in trust for unborn generations of Crow and Comanche, Pueblo and Cheyenne, Hidatsa and Cherokee—where people who know who they are gather around half moon kitchen tables to make laughter and share grief. Still there after the storms.

Paul VanDevelder is a writer and documentary filmmaker based in Oregon. His book Coyote Warrior: One Man, Three Tribes, and the Trial That Forged a Nation was nominated for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 2004. His latest book is Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire Through Indian Territory.

Paul VanDevelder is a writer and documentary filmmaker based in Oregon. His book Coyote Warrior: One Man, Three Tribes, and the Trial That Forged a Nation was nominated for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 2004. His latest book is Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire Through Indian Territory.

!["Four Indian Riders." Fritz Scholder 1967. Oil on canvas. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. William Metcalf. Photo by Walter Larrimore, NMAI. [Click to view larger image.]](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/image/2009/American%20History/fritz-scholder-four-indian-riders-600.jpg)