A political insider gives his view on what went wrong

Rufus Phillips served with the Army, CIA and U.S. Agency for International Development in South Vietnam from 1954 to 1968, working undercover and on “pacification” projects to provide security, economic development and social services in rural areas. He put his expertise to use as an adviser to U.S. officials, including Vice President Hubert Humphrey, and attempted to steer government policy toward actions that would achieve a “meaningful outcome” in the war, but he had little success. In Why Vietnam Matters, Phillips draws on his experiences to catalog the reasons for the war’s tragic ending.

The United States in July 1968 was a country in severe turmoil. Parts of Washington remained in smoking ruins from the riots after Martin Luther King Jr.’s death on April 4. Robert Kennedy was dead, shot on June 6, while campaigning in the Democratic Party’s presidential primaries. And the anti-war movement had become a dominant force within the party. Vietnam was the critical issue on which the November presidential election would turn.

The American people had never been given an adequate explanation of why we were there, what was truly at stake and how a different approach might have worked. That’s because our leaders had never understood the war themselves. We were trapped in unrealistic hopes for negotiations with the North Vietnamese, while they were determined to wait us out, not giving an inch of legitimacy to the South Vietnamese cause. They demanded that South Vietnam be forced into a coalition with the Viet Cong, combined with complete American withdrawal. They would continue to expend manpower, maximizing American casualties and waiting for public opinion to turn completely against the war. This strategy had succeeded with the French; now it was America’s turn.

A Policy Paper for the New President

I did what I could to help Hubert Humphrey in his 1968 presidential campaign. In a memo to him I concluded that he desperately needed to develop a winning strategy for Vietnam. There were real experts on Vietnam in various places in Washington who would be willing to help develop such a strategy without publicity or expectation of future reward.

I suggested the vice president take the initiative in assembling such a group informally. I got the verbal go-ahead from Bill Connell, the vice president’s administrative assistant. Originally drafted for Humphrey, our paper evolved into a policy statement that could be used by whichever candidate won. We finished a final draft in late October as the presidential campaign wound down, with Democrat Humphrey surging at the end but too late to catch Republican candidate Richard Nixon.

I suggested the vice president take the initiative in assembling such a group informally. I got the verbal go-ahead from Bill Connell, the vice president’s administrative assistant. Originally drafted for Humphrey, our paper evolved into a policy statement that could be used by whichever candidate won. We finished a final draft in late October as the presidential campaign wound down, with Democrat Humphrey surging at the end but too late to catch Republican candidate Richard Nixon.

Our paper, “A Political Strategy for Vietnam,” 23 pages with an appendix on recommended actions, covered the military and political situation in Vietnam, the mood of the American people, meaningful outcomes and alternative courses of action, a political strategy, and a conclusion.

A meaningful outcome was a “South Vietnam free from North Vietnamese attack, reasonably independent, relatively stable, responsive to the needs of the South Vietnamese people and increasingly able with allied help to assume the main burden of the fight against the South Vietnamese communists . . . moving forward sufficiently to allow de-Americanization and a gradual reduction in visible U.S. presence which would serve as a catalyst in the Vietnamese nation-building process and assuage an uneasy American public.” Major liabilities were the uninspiring nature of South Vietnam’s leadership; the weakness of its political organizations; the Viet Cong’s determination and effectiveness; our inferior, not superior, position in the Paris peace negotiations that had begun in the spring of 1968; South Vietnamese shortcomings in confronting the communist political and military challenge; and the fact that a classic military victory alone would not necessarily lead to long-term political stability.

Alternatives were continuing to rely mainly on military pressure to influence the war’s course and the Paris talks; stepping up military operations; or decreasing our effort unilaterally, regardless of what the other side did. Our recommended course was to pursue a political/military strategy designed to strengthen the South Vietnamese in their political confrontation with the Viet Cong while phasing down the visible U.S. presence.

Unlike in the past, proposed actions had to improve Vietnamese military and political effectiveness in ways the Vietnamese would accept and support.

October Surprise

In the middle of October, Humphrey was eight points down in the opinion polls. On Oct. 31, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced a halt to the bombing over most of North Vietnam and the resumption of stalled peace talks in Paris, to begin on Nov. 6, one day after the election. There was an instant reaction in public opinion. By Nov. 2 the gap in the polls had closed: 40 percent for Humphrey, 42 percent for Nixon.

For some time, the Americans and South Vietnamese had conducted a delicate dance regarding peace talks with the North. The South Vietnamese needed to be treated as equals by the North, which the North was not willing to do. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu, like most his country’s leaders, feared that the peace talks would elevate the Viet Cong to equal status with the Saigon leadership and force a coalition government. “Coalition” was a dirty word to most non-Communist Vietnamese, who remembered that Ho Chi Minh lured nationalist political groups and leaders into alliances and then betrayed them.

Thieu wanted the next American president to be the man most likely to stand with South Vietnam in refusing to concede anything to the Communists. He believed his most reliable ally would be Nixon, not Humphrey. That was not understood in Washington, where Johnson thought Ellsworth Bunker, the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, had the situation under control.

By the time Johnson made his Oct. 31 announcement, he had not received an unequivocal indication of South Vietnamese intentions concerning the peace talks. He finessed the matter, declaring that the South Vietnamese were “free to participate.” Thieu had said nothing to indicate he would not join the talks, and Bunker had taken this for assent. But in a speech to the Vietnamese National Assembly on Vietnamese National Day, Nov. 1, Thieu declared, “South Vietnam deeply regrets not being able to participate in the present exploratory talks.” He received 17 standing acclamations during his defiant address. Bunker was completely surprised. South Vietnamese reaction to the speech was overwhelmingly favorable—they would not be dictated to by the Americans. Expectations that had lifted the Humphrey campaign received a dash of cold water, as The Washington Post headline stated, “S. Vietnam Spurns Nov. 6 Talks.”

The Americans had no one on the inside to know what Thieu truly intended. The great disconnect between American officialdom and the Vietnamese continued.

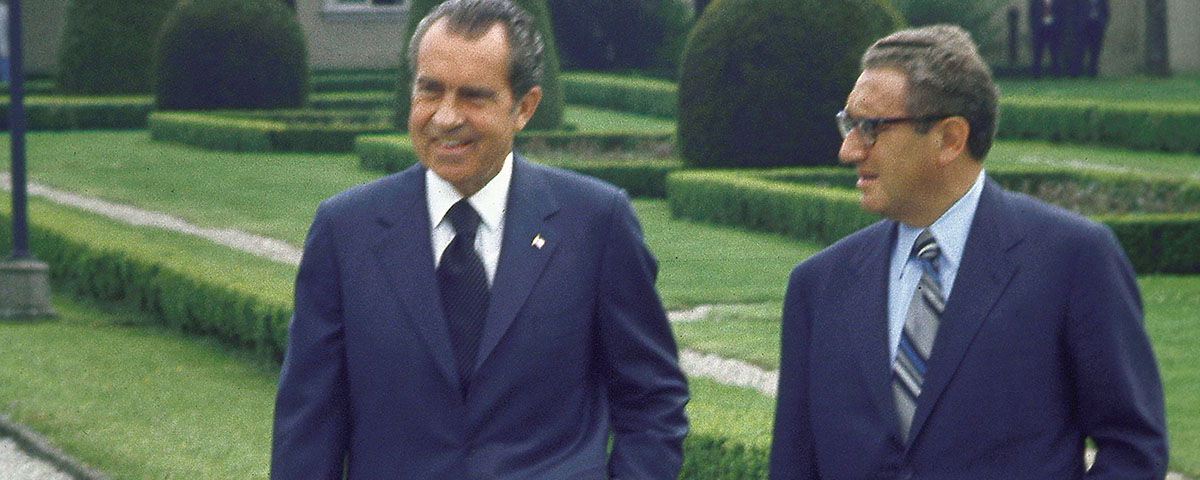

Nixon and Kissinger

The Nixon administration, which took office in January 1969, pursued a policy of “Vietnamization,” an accelerated training of the Vietnamese armed forces to take over the fighting, combined with a gradual drawdown of American troops. Gen. Creighton Abrams, who had become the American commander in Vietnam in June 1968, pursued a strategy different from the course chosen by Gen. William Westmoreland, his predecessor at Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

Westmoreland’s war of attrition had backfired. Abrams changed the emphasis to protection of the civilian population, better arms and support for local forces, doing away with free-fire zones and concentrating on Vietnamese pacification efforts, while emphasizing smaller and more flexible American operations against still increasing North Vietnamese regulars. Pacification largely succeeded, but combat losses continued at a rate unacceptable to the American public, which turned more and more against the war, its opposition aggravated by actions such as the invasion of Cambodia by American and South Vietnamese troops in the spring of 1970.

The emphasis on stability versus democratic reform in Saigon added to the disenchantment. The South Vietnamese government was perceived as corrupt and dictatorial, unworthy of the sacrifice of American lives.

Nixon’s decision to resolve the conflict through big-power politics and secret negotiations was not something that could be credibly explained to the public, as the expenditure of American lives and treasure continued. Nixon completely ignored another alternative: refocusing our efforts on helping the South Vietnamese construct a viable and attractive democratic political cause, which could have fueled a united will to resist and therefore have resonated with American opinion.

Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, negotiated a peace treaty with North Vietnam in 1973, but the result was not “peace with honor,” as Nixon proclaimed. It was the collapse of South Vietnam under the assault of the North Vietnamese Army and the imposition of a Communist tyranny, with tragic results for the South Vietnamese people.

Kissinger got our paper and presumably read it, but our conclusion was that it had never received serious consideration.

Political Weakness, Pacification Progress

The 1971 South Vietnamese presidential election had been perhaps the last chance for political reform and the establishment of a viable political cause around which various political and religious factions could unite. It was also the last chance to improve the Vietnamese government’s image in the eyes of the American public. Unfortunately, because the American focus was on regime stability, we did not use our influence to bring about an open and competitive political process. Thieu ran unopposed in a blatantly unfair process.

Kissinger’s attitude, as stated in his memoirs, was: “While Thieu’s methods were unwise, neither Nixon or I was prepared to toss Thieu to the wolves: indeed short of cutting off all military and economic aid and thus doing Hanoi’s work for it, there was no practical way to do so. We considered support for the political structure in Saigon not a favor done to Thieu but an imperative of our national interest.”

South Vietnamese political progress was sacrificed to keep an essentially weak, often vacillating regime in place to facilitate peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. When the Paris Peace Accords were announced on Jan. 27, 1973, it became clear that a substantial Communist force, some 150,000 to 200,000 North Vietnamese regulars, had been allowed to remain in the South. If one understood the terms of the accords, there was little to celebrate. Kissinger, whose negotiations earned a Nobel Peace Prize in October 1973, deserved no award, except one for deception.

Despite the gains in pacification, the South Vietnamese government remained vulnerable. Thieu improved his standing by pushing through real land reform and supporting pacification, but he never generated the widespread political support that a more genuine democratic effort could have engendered. Although able to rally the nation during the North Vietnamese Army’s 1972 Easter Offensive, Thieu’s government offered too little political outreach and indulged in too much nepotism and corruption to sustain public confidence.

As early as 1967, Bui Diem, South Vietnam’s ambassador in Washington, had begun warning Thieu that American support could not be expected to continue more than another five years. He was reading the signs in Congress and public opinion, but Thieu persisted in thinking to the very end that America would never abandon Vietnam.

All American units and military advisers withdrew after the 1973 peace agreement. Supporting equipment, weapons and ammunition, already reduced, were more than cut in half for 1974. That left the South Vietnamese army without adequate supplies and U.S. logistical support, which meant it was not capable of moving rapidly enough to face a North Vietnamese offensive. Nor was the South Vietnamese air force capable of bombing North Vietnamese units without being shot down by missiles or anti-aircraft fire. There was no sufficiently strong and experienced command structure in place for all key units.

With adequate American aid as well as logistical and air support, the South Vietnamese government under Thieu’s leadership might have sustained itself politically and militarily over the long run, but the regime suffered from institutional weakness, internal corruption and cronyism. South Vietnam lacked a unifying political cause in the form of representative and responsive national government under inspired leadership, something the average Vietnamese could feel was worth risking one’s life to defend—and which might have changed American public opinion. Whether this critical failure could have been overcome by a different American and Vietnamese approach is a question to which there can be no definitive answer. Certainly, it was never seriously tried.

The Tragic Aftermath

Before the peace agreement, Nixon had secretly promised Thieu “to respond with full force should the settlement be violated by North Vietnam.” He also promised continued economic and military aid. In the meantime, the anti-war movement had grown so much that when the Watergate scandal led to Nixon’s resignation in August 1974, Congress cut off further support. The Vietnamese were left alone, with the dwindling military supplies and equipment they had on hand and with no effective air support. The door was wide open for an outright invasion of the South by the full weight of the North Vietnamese Army. That took place in 1975, and South Vietnam had collapsed by the end of April.

First impressions of the North Vietnamese takeover appeared more benign than expected, considering the mass executions by the Communists in Hue during the 1968 Tet Offensive. More careful about their international image, the Communists hid from the public their executions—mainly of South Vietnamese intelligence personnel, special police, provincial reconnaissance teams, Nationalist political party members in the provinces, suspected spies for the Americans and former Viet Cong considered traitors for surrendering under the South Vietnamese government’s amnesty program and fighting for that side.

In addition, all government officials and private businessmen above the rank of clerk and all officers of the South Vietnamese armed forces, as well as employees of the Americans, an estimated 300,000 to 400,000, were rounded up and marched to special indoctrination camps, the Vietnamese version of the Soviet gulag. Many were kept there for 10 years, some for as long as 17, and a number died of deprivation and disease. Also arrested and held in prison for several years on “suspicion” were active supporters of the Viet Cong who had neglected to join the movement formally.

Agriculture was collectivized, and more than a million city dwellers were driven into “special economic zones” in the countryside, where they were expected to make a living. How many starved to death is unknown. Ordinary South Vietnamese soldiers and former government civilians were denied jobs, and their children were denied entrance to high schools and universities. Even South Vietnamese army cemeteries were uprooted. It was mass vengeance.

Then came the exodus of more than a million people in boats who fled across the South China Sea toward the Philippines or across the Gulf of Thailand toward Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. Those escaping were not only former regime families or supporters but ordinary farmers and fisherman as well.

The Communist takeover of South Vietnam, which was followed by Communist victories in Cambodia and Laos, also sounded the death knell for an estimated 1.8 million Cambodians and several hundred thousand Lao, including members of the Hmong tribe that had assisted U.S. forces—adding to the number of people executed or deliberately eliminated by maltreatment in camps, prisons or the countryside.

The South Vietnamese did not deserve that fate. The war’s ending also left Americans with a moral dilemma we have yet fully to confront. After becoming so deeply involved and significantly hindering (as well as helping) the attempts of the South Vietnamese to defend themselves, were we right to abandon them in 1975, without at least providing as much help as we had in 1972 when they had repelled the previous North Vietnamese invasion?

Why We Failed in Vietnam

In an interview before his death, Gen. Maxwell Taylor, the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, July 1964-July 1965, concluded we failed in Vietnam because “we didn’t know ourselves,” He said, “We thought we were going into another Korean War, but this was a different country. Secondly, we didn’t know our South Vietnamese allies. We never understood them, and that was another surprise. And we knew even less about North Vietnam.”

Former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, in his book In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, said U.S. decision-makers were “setting policy for a region which was terra incognita.” But then he excuses the mistakes, arguing that “our government lacked experts for us to consult to compensate for our ignorance.” He recognizes Air Force Col. Edward Lansdale (later a major general) as one expert but dismisses him because he “was relatively junior and lacked broad geopolitical expertise.” McNamara simply rejected advice that did not conform to his preconceptions. No set of “experts” could have overcome that obstacle.

We failed to understand the “X-factor”—the political and psychological nature of the struggle for the “hearts and minds,” the feelings of the Vietnamese people. We failed to communicate with or understand the Vietnamese on a human level, often confusing increased numbers of staffers with greater influence. We underestimated the motivating power of Vietnamese nationalism, and we failed to comprehend the fanatical determination of an enemy willing to sacrifice its entire people until only the Politburo was left. We failed to comprehend the intimate connection between our actions in Vietnam and political support at home. Above all, we failed to understand that the South Vietnamese could never stand on their own unless they were able to develop a political cause as compelling as that of the Communists.

Absolutely fatal was the failure to explain openly and honestly to the American people what we were trying to achieve. Our lack of understanding and miscalculations at the top led us to justify a massive commitment of American troops as the best way to achieve a quick military victory. When victory failed to materialize and stalemate seemed to set in, public support was lost. The image of American boys sacrificing their lives while, it seemed, the South Vietnamese were profiteers, refusing to fight, was corrosive.

Whether the South Vietnamese could have hung on after our withdrawal with all-out logistical and air, as well as advisory, support from us is an open question. That would have given them a better chance to survive in the short run, but in the long run they still needed to accomplish the democratic reforms necessary to unify their society and to develop a political cause capable of challenging the Communists.