When Charles O. Hunt, a lieutenant in Captain Greenlief Stevens’ 5th Maine Light Artillery, marched into Gettysburg, Pa., with the Army of the Potomac’s 1st Corps in the summer of 1863, it must have felt like a homecoming. Hunt was from Gorham, Maine, but after graduating from Bowdoin College in 1861 he had spent time in Gettysburg visiting his sister, Mary Carson. From September through the end of 1861, Hunt stayed in the Pennsylvania crossroads town with Mary and her husband, Thomas, a clerk for the Bank of Gettysburg on York Street. Hunt contemplated his future as he became familiar with the town and the surrounding countryside. He hiked the Round Tops, rode across the yet-to-be-bloodstained Wheatfield, and collected hickory nuts on Culp’s Hill.

Hunt’s contemplations led him to decide to fight for the Union, and he returned to his home state and joined the 5th Maine Artillery, then under the command of George Leppien, a Pennsylvanian who had received military training in Germany. On December 16, 1861, Hunt was promoted to quartermaster sergeant of the battery. After Leppien was mortally wounded at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Stevens was promoted to captain and took command of the battery; Hunt was promoted to 2nd lieutenant. He was one of three lieutenants in the 5th Maine, each responsible for a section, or two cannons, of the six 12-pounder Napoleons that made up the battery.

As the 5th Maine marched north to Pennsylvania on July 1, Hunt joked to Stevens that if he were to get hit, he hoped it would happen in Gettysburg, as he knew the people there would take good care of him. The Maine gunners were quickly sent to Seminary Ridge after reaching Gettysburg and deployed in two locations. One was on a ridge just south of the Chambersburg Pike in the vicinity of the C.P. Kranth house.

Stevens’ battery was heavily engaged at that point, with Brig. Gen. Alfred Scales’ North Carolinians having the misfortune of charging against the belching muzzles of the 5th Maine’s Napoleons. The Pine Tree State artillerymen lobbed case shot and then blasted 57 rounds of canister at the Tar Heel mob struggling toward the western face of Seminary Ridge, and Scales noted in his official report that his brigade weathered a “most terrific fire of…grape…in our front. Every discharge made sad havoc in our line….” Scales’ Brigade suffered 545 casualties during the attack.

As the battle continued to roar and their guns continued to deal out destruction, Hunt and the rest of the 5th Maine’s gunners had a hard time seeing the enemy approach through a thick layer of gunsmoke that had settled into the swale at the western foot of Seminary Ridge. That literal fog of war caused Hunt to move forward for a better look, and a Rebel bullet found the lieutenant just after he returned to his guns, as he described in the following account.

On July 1st, at an early hour, we marched with the rest of the 1st Corps towards Gettysburg. [Brig. Gen. John] Buford, with his cavalry, was having an unequal fight with the enemy’s advance, and [Maj. Gen. John] Reynolds hurried the 1st Corps up to his relief. As we approached Gettysburg we turned off from the Emmittsburg road to the left towards the Seminary ridge. At first we went into position some distance south of the Seminary buildings but we were not engaged at this place. Later we were moved to the North side of the seminary buildings. By the time we were in position the enemy were coming over the ridge which runs parallel with the Seminary ridge. We opened with case shot at first, firing over our Infantry who were in front of us on lower ground. As they fell back to the line of the guns we used canister. While we were using case shot I found it very difficult, on account of the smoke, to see whether they were exploding in the right place. To get out of the smoke, I climbed over a fence at the left of my section and went behind the house. I remember very well the sound of the bullets on the brick house, reminding me of a shower of hail on the roof. Soon after I returned to my position with my section, I was wounded in the upper part of the right thigh. I did not at first realize what had happened. I felt a sharp sting, as if I had been struck a slight blow with a light cane. On looking down I saw a jagged hole in my pistol holster, which was on my belt. On trying my leg I found, to satisfaction, that the bone was not broken. Feeling that the wound was too serious to admit of my doing any further service in that fight, I limped to the capt. and reported, and asked permission to go to town to see my sister while I was able to do so. In the morning, before going into action, I had remarked jokingly to the capt. that if I was ever going to be hit I hoped that it would come there, for I would be sure of being well taken care of. So my wish was granted.

With help I was able to mount my horse and I rode slowly into town. Even then the enemy’s shells were beginning to rake the road, and the ride was anything but a pleasant one. On my arrival at Mary’s, I think Tom and Dr. Charles Herner were at the door, and I found that the rest of the family, with many neighbors had sought shelter from the enemy’s shells in the bank vault. The bank adjoined the house, with a private door from the hall for the convenience of the cashier. Some time before this a recently spent shell had come in through an attic window and, after going through the stairs, had dropped down the well of the staircase to the front hall. This had frightened them not a little and had caused their retreat to the vault. The contents had been sent to Philadelphia when it was found that Lee was to invade Pennsylvania. I believe there were nineteen women and children and two dogs in the vault when I arrived.

Soon after this our lines fell back, retreating through the town towards Cemetery Hill. While they were passing through the town, the enemy’s shells came down the streets and overhead in great numbers. There was much excitement among the occupants of our house. The women and children went to the vault, and for my safety they carried a mattress to the cellar and I lay there for some time. While I was there the rebels occupied the town and, soldier-like, the first thing they thought of was something to eat. Through a crack in the door, I saw two Rebs come into the back cellar and strip the pantry of everything eatable. I did not care to remonstrate.

But in a very short time the town was quiet and my friends came out of their hiding place and soon had me put to bed in the front chamber where Dr. Herner dressed my wound. When I had first arrived he had recovered with his fingers a flattened ball from the superficial part of the wound. But on probing he found that there was something more there, which, on extraction, proved to be about an inch and a quarter of the iron rammer of my Colt’s revolver. The ball had struck the pistol between the barrel and the rammer, knocking out this portion of the latter and bending the barrel (this pistol is one of my relics). On account of this piece of rammer being driven into my thigh, the wound was a large and jagged one.

While the doctor was engaged in dressing the wound, two Rebel officers came into the house. Mary saw them coming up the stairs. They asked her if there were any soldiers in the house. Mary, with many misgivings, had to confess that she had a brother there. They said they were sorry, but they would have to take him. Then she mentioned the fact of my being wounded. This altered the case, and they said they wanted to see me. So Mary brought them into the chamber. They were very courteous and expressed regret for my hurt. One of them said to the other, “Had we not better parole him?” To which the reply was, “We can do that some other time. There will be plenty of time.” From which I judged that they thought they had come to stay. On leaving they said to Mary “Take good care of your brother and don’t let him fight us any more.” Mary replied that she would take good care of me but she could not promise as to the rest of it.

This first night I spent in the front chamber. There was an occurrence in the street below my window which illustrates the rigid discipline they maintained while they were in possession of the town. Across the street was a grocery store, and the owner also carried quite a large stock of liquors. Sometime in the night I was awakened by hearing someone sternly command “come out of there.” Then—“Throw it down” which was succeeded by a crack on the pavement, and this was repeated over and over again. I could imagine the procession of disappointed “Johnnies” coming out of the cellar, each with his bottle, jug, or demijohn, which he was obliged to smash on the pavement. I will say right here that there was surprisingly little disorder during the two days and a half that they held the town. I think they cleaned out provisions and grocery stores pretty generally, but the private houses were not disturbed. The men were not allowed to get at the liquors, and I never heard of any drunkenness. On the evening of the 3d[,] a man came to the front door and rather roughly demanded food. Mary refused on the ground that she had very little in the house—a very short supply for her own family. He was quite abusive and tried to enter the house, but Mary managed to get the door shut and locked it in his face. He swore he would come back and burn the house down before morning.

My recollections of the details of the events of July 1st, 2d & 3d are not very distinct on this late day, but there are certain features that can be recalled very vividly. One was the horrible crash of musketry at the time of the attack on Culp’s hill near the close of the 1st. As that was quite near our part of the town, it came to us with great distinctness. The sound of musketry is always more apalling [sic] than the roar of artillery.

The great artillery fight, which preceded Pickett’s charge on the 3d, was also something not to be forgotten. As the town lay, in a sense, between the two fires, the uproar seemed more terrible to us than it would if we had been on either line. At that time I was lying on a mattress in the dining room, as houses in our immediate vicinity had been occasionally struck by shells, and it was felt that it would be safer there. The house was an old fashioned brick house of solid construction but it trembled to the very foundation. The earth literally shook.

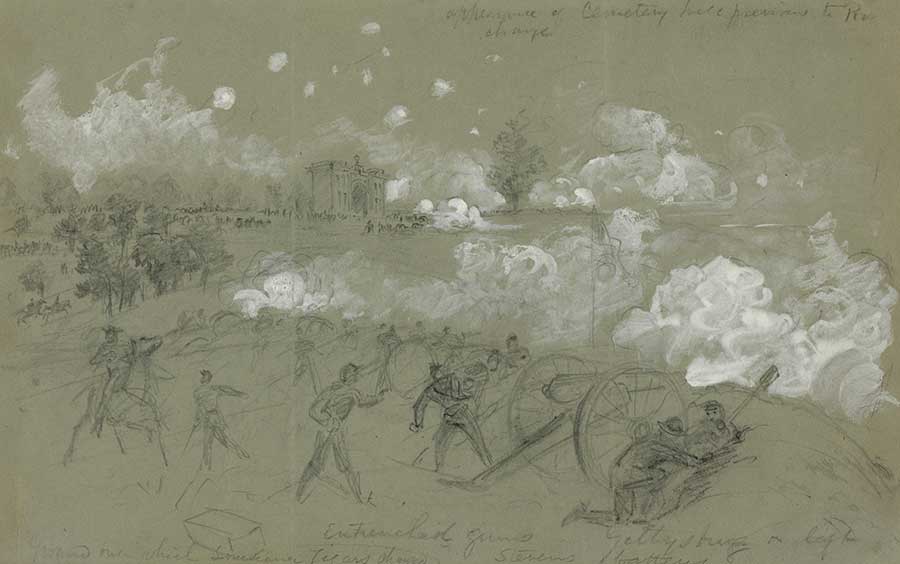

Seminary Ridge to Stevens Knoll

The 5th Maine Battery kept up its July 1 fight on Seminary Ridge for several hours after wounded Lieutenant Hunt went to the rear. But Union resistance west of Gettysburg finally collapsed late in the afternoon, and the Maine gunners hitched up their cannons and moved to a knoll to the “right and rear of Cemetery Hill,” as it was described in the battery’s official report. The Maine soldiers restocked their empty limber chests and to protect their Napoleons threw up earthworks with the help of infantrymen.

On July 2, some of the roaring artillery that Lieutenant Hunt undoubtedly heard while confined in his sister’s house came from his batterymates, who were engaged throughout the day. That included a fierce bombardment against Brig. Gen. Harry Hays’ and Colonel Issac Avery’s Confederates as they attacked the eastern face of Cemetery Hill after sunset.

Captain Greenlief Stevens had been wounded by a sharpshooter, leaving Lieutenant Edward N. Whittier in command. Whittier later wrote that his battery unleashed blasts of “spherical case and shell, and later…solid shot and canister” as the Confederates swept toward the Union defenses on Cemetery Hill. The rapid fire emptied “the entire contents of the limber chests,” he recalled, and after the Rebel attack had been repulsed, he temporarily pulled the battery back to acquire new ammunition. In his report, Whittier thanked the soldiers of the 33rd Massachusetts and the Iron Brigade’s 24th Michigan for helping serve the cannons and running ammunition when some of the artillerymen became “temporarily exhausted” by the hours of prolonged firing on July 2.

The battery also sparred with Confederate artillery the morning of July 3, but otherwise had a comparatively quiet day. The 5th Maine would suffer 23 casualties at Gettysburg, and fired a whopping 979 rounds—mostly on Days 1 and 2. Captain Stevens would heal and rejoin his command, and later served on the state of Maine’s Gettysburg Monument Commission. His name forever became part of the battlefield’s lexicon when the hillock the 5th Maine sternly defended on July 2 was renamed “Stevens Knoll.” –D.B.S.

History tells us that Gen. [Henry] Hunt, Chief of Artillery for our army, after this artillery duel had been kept up for a considerable time, ordered our batteries to cease firing in order that the guns might cool, and all things be made ready for the Infantry charge, which he knew must soon come. The rebels also ceased firing very soon after thinking that they had silenced our batteries. The suddenness in the cessation of the tumult filled us with apprehension. The silence was awful. “What can it mean?” was the question that everyone asked, but none could answer. We had not long to wait before it all began again, and soon to the roar of artillery was heard the crash of musketry.

The most trying feature of our situation was our ignorance of how the battle was going. I could generally know that our guns were still in position by noting the explosion of shell, but beyond that we could learn nothing. During the whole period of the battle we were oppressed with the most intense anxiety.

On the morning of the 4th, as soon as it began to be day light Mary’s old servant went out to a neighbors on some errand, and soon came back saying that she believed the rebels had gone; that not one was to be seen in the streets. The good news was soon confirmed and the strain of the anxious three days gave way to rejoicing. Before long cavalry came in and occupied the streets, and they were followed by infantry, and we knew that the battle of Gettysburg had been won.

Before very long it was discovered that, although the enemy had left the town, they had not taken their departure for good. They had a strong line of artillery posted on the Seminary ridge facing the town. In some way the rumor was circulated that they proposed to shell the town and destroy it. This caused greater excitement among the citizens than there had been during the fight. A great many started at once for the country in the opposite direction, carrying in their hands what seemed to them most valuable. Many amusing stories were told of the curious selection that some made in their excitement.

What to do with me, worried Thomas and Mary more than it did me. I did not believe the rumors, and even if it should be true, I felt that we would be quite safe in the cellar. But I could not convince them. The only conveyance they could find was a wheelbarrow, owned by their next neighbor Mr. Creasy, and I believe he volunteered to do the wheeling. I protested against such an undignified exit and persuaded them to postpone the start till there was some certain evidence that the enemy would carry out their supposed threat. It is needless to add that the wheel-barrow was not called into requisition.

O]n July 4 Hunt wrote a letter to his mother, also named Mary. “Here I am lying on my back in Mary’s back parlor making myself as comfortable as possible,” he wrote. “I suppose before this reaches you, you will have heard that I was one of the victims of the great fight of Gettysburg, but I hope you have heard an exaggerated account. My wound is very slight and I shall be about again in two weeks at most….I think I shall be just comfortably convalescent in time for commencement at Brunswick. I think I am the luckiest dog that ever lived. To think that I should have been wounded here! I have managed to get here every time that anything has been the matter with me.”

Lieutenant Hunt recuperated in Gettysburg until July 28. After healing, Hunt returned to Maine and rejoined his battery in the fall. On June 18, 1864, he was captured outside Petersburg. With the exception of an escape attempt from Columbia, S.C., in November 1864, he remained in Confederate prisons until he was paroled in February 1865. Hunt became the Maine General Hospital’s superintendent after the war and married Cornelia Carson. Together they raised a daughter, Helen.

But his old leg wound never let him forget July 1, 1863. He received a military invalid pension in 1869, and his pension file at the National Archives contains several surgeon’s certificates that describe the deleterious impact of his wound. One claimed his thigh “was very painful at times….” Hunt was awarded a pension of $7.50 a month. In 1904, a surgeon said the injury had left a scar “one inch in diamerter [sic]….There is loss of tissue around the scar, and much anesthesia,” or nerve loss. Hunt’s pension was increased to $10 a month. In 1909, Hunt “dropped dead” at a Portland, Maine, railway station, according to a local newspaper, 46 years after he suffered his Gettysburg wound. He was 70 years old. Hunt’s handwritten memoirs and the transcriptions of his letters fill two bound volumes in the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives at Bowdoin College.

Tom Huntington is the author of Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg, and numerous magazine articles. This article was adapted from (Stackpole Books, 2018).

A Mother’s Plea

Mary G. Hunt, 2nd Lt. Charles O. Hunt’s mother, had already lost a spouse and two sons before the Civil War. Her husband, also named Charles, had died in 1844, and two of her four boys had died as infants, leaving her with sons Charles and Henry, and a daughter also named Mary. After Charles was taken prisoner at Petersburg, mother Mary wrote the following letter, found in Charles’ service record file at the National Archives, to Maine Senator and Secretary of the Treasury William Pitt Fessenden (above), hoping to obtain his release. Mary had no way of knowing that her son was actually in the midst of an escape attempt from his Columbia, S.C., prison when she was writing her plea. After more than two weeks on the run, Hunt and his two fellow escapees were recaptured and sent to a prison in Danville, Va.

In her letter to Fessenden, Mary frets over her son’s health, and claims he was one of the prisoners the Confederates had deliberately quartered in the path of incoming artillery fire at Charleston, using them as human shields against incoming Union bombs. Lieutenant Hunt’s service record also contains a second letter written to Fessenden by a family friend, the content of which mirrors Mary’s letter.

Fessenden sent Mary’s letter on to Maj. Gen. Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the “Commissioner for the Exchange of Prisoners,” who scribbled some notes on the missive that a subordinate polished into a response to her, also in Lieutenant Hunt’s file and transcribed below. While she was undoubtedly disappointed by the answer, Mary would have many postwar years to spend with her sons before she died in 1893. Charles was finally paroled, according to a prisoner memorandum in his service record, on February 22, 1865, at “James River, Va.,” and his brother Henry, who served as a private in the 5th Maine Battery, and who spent much time detailed as a hospital steward, was discharged at war’s end.–D.B.S.

Gorham, Me., Nov. 9th 1864

Hon. Wm. P. Fessenden

Dear sir you will excuse a widowed mother for taking the liberty of addressing you, in behalf of her son.

Lieut. Charles O. Hunt of the 5th Battery Maine Vols. who is now a prisoner in Columbia S.C. He was captured last June near Petersburg taken to Macon, then to Charleston, to be placed under fire, together with other officers where he remained until Oct 6th.

They were then removed to Columbia and there turned into an enclave like so many cattle, without shelter from storms and the chills of night-and supplied with food both poor in quality and scanty in quantity.

He was never very strong, unused to hardships, and I fear he will sink under this double exposure. I have only two sons both graduates of Bowdoin. Charles in 61 and his brother in 62. Then both entered the service of their country. They are both on their third years service, Charles third year expires next month, but he intends to remain in the service till this conflict is over if his health is [illegible]. He has been in many battles, had typhoid fever, was wounded at Gettysburg, but my heart aches for him now as never before. I would earnestly request if there is any influence you can exert on his behalf you will use it to bring about an exchange. He writes me that especial exchanges are going on continually some going out by every flag of truce lost in this way.

Dear sir I say once more excuse me for this liberty. But I do feel assured that you have the power to bring this about in some way, and I do hope you will speak a word for him.

May the blessing of Heaven rest upon you in all your arduous duties.

Yours very respectfully,

M. G. Hunt

War. Dep’t, W.C., [Washington City] November 18th, 1864

Madam:

With reference to your letter of the 9th instant, addressed to the Hon. W.P. Fessenden, requesting a special exchange for your son, Lieutenant Charles O. Hunt of the 5th Maine Battery, now a prisoner to the rebels. I am instructed to state that special exchanges are not made except for reasons of public character, but that the Department is using every means in its power to effect a general exchange of prisoners of war, and that arrangements are in process to send supplies of all kinds to the Federal prisoners of the South. Due attention will be given to the case of Lieutenant Hunt, with a view to his release at the earliest possible period.

Very Respt, [respectfully]

Yr Obd Svt [Your Obedient Servant]

L.H.P. Mrs. M.G. Hunt

Gorham, Maine

[/box]