In the 1930s and ’40s, Arturo Toscanini, the most celebrated conductor of opera and symphonic music in history, was also the best-known opponent, among musicians, of Nazism and Fascism. The man who had worked directly with Verdi, Puccini, Debussy, Richard Strauss, and many other composers—the man whose hatred of compromise had allowed him to carry out major reforms in musical performance practices—was also the man who stood up to Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

The story of Toscanini’s opposition to totalitarianism begins long before his birth in Parma, Italy, in 1867. Claudio Toscanini, the future conductor’s father, was by trade a tailor but by nature what the Italians call a scalmanato—a hothead, a person who feels fully alive only in a state of agitation. Born in 1833, Claudio from an early age believed deeply in the Risorgimento, the unification of Italy. He joined Giuseppe Garibaldi’s irregular army in 1860 and that year followed the general through the Sicilian campaign, which paved the way for Italian unification in 1861. He enrolled in the regular army’s Bersaglieri Corps but deserted in 1862 to rejoin Garibaldi in the ill-fated attempt to snatch control of Rome from Pope Pius IX. Captured at the Battle of Aspromonte, Claudio spent three years in prison before being pardoned and returning home to Parma, where he married and became the father of four children. Arturo was the firstborn. Claudio inculcated in his son a love of Garibaldi, of Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary, and of freethinking, along with a contempt for the Italian monarchy and for the Church of Rome, and an unshakable belief that the Trento and Trieste regions, which were still in Austrian hands, rightfully belonged to Italy.

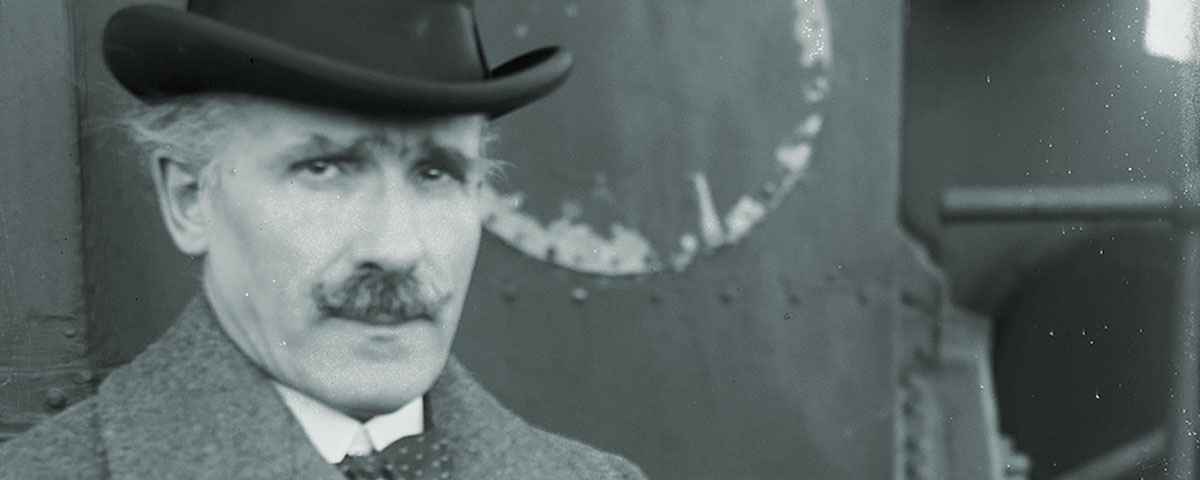

Arturo Toscanini, who was endowed with extraordinary musical gifts as well as a photographic memory, began his conducting career at age 19; by age 30 he had conducted dozens of opera productions (including the world premieres of Pagliacci and La Bohème) and symphony concerts all over Italy and had taken charge of La Scala (Milan), Italy’s greatest opera ensemble. In 1908 he became co–principal conductor, with Gustav Mahler, of the Metropolitan Opera in New York. In the spring of 1915 he returned to Italy and supported the Italian government’s decision to break its pact with Germany and Austria and to join the Great War on the side of Britain and France. For the duration of the war he conducted only benefit performances, and he was forced to sell his home in Milan to provide for himself, his wife, and their three children.

In the summer of 1917, at the invitation of General Antonino Cascino, the 50-year-old Toscanini formed a military band and took it to the front, along the Isonzo River; he led it up the 2,250-foot Monte Santo and conducted it as the infantry, less than a mile away, fought to capture another mountain from the Austrians. “We played in the Austrians’ faces,” Toscanini wrote to his son, who was fighting in a nearby division. The commander of the Army of the Isonzo awarded him a silver medal for military valor. A New York Times war correspondent reported, a few days later: “Wherever I have been on the Italian front Toscanini had been there first.”

The band gave informal concerts in makeshift venues but also played in the trenches and wherever else it was sent. On October 28, 1917, while the musicians were performing in the town of Cormons, they suddenly noticed that they were practically alone in the piazza: The Austrians were approaching, the Italian army was withdrawing, and the General Command had forgotten about the band. Toscanini rushed to procure wagons and railroad cars to evacuate everyone to safety. It was fortunate he succeeded, as the town was swept up in the disastrous Battle of Caporetto—a name that to Italians remains synonymous with “defeat.”

Although Italy and its allies won the war, the Italian government’s inability to deal with postwar social and economic turmoil persuaded Toscanini that drastic changes were needed. Early in 1919 his son Walter persuaded him to attend a political meeting held in Milan by a former editor of the Italian Socialist Party’s newspaper, Avanti!—one Benito Mussolini, who at the time advocated a Bolshevik–like platform that included abolishing the monarchy, the nobility, the banks, and the stock exchange; giving the vote to all adult Italians; and confiscating church property. Toscanini was impressed, and when, at the last moment, Mussolini decided to put forward a list of candidates in Milan for the November parliamentary elections, Toscanini’s name appeared sixth on the slate. But the Fasci di Combattimento (Fighting Leagues), as the new party was known, received fewer than 5,000 votes; the Milanese Socialists received 170,000. Many thought Mussolini’s political career was over, but in fact he had merely lost his taste for the Left—and for elections. As for Toscanini, his unwanted political career had indeed come to an end, at least officially.

In 1920 Toscanini resumed the artistic direction of La Scala, and he began by reorganizing the house orchestra and taking it on a marathon tour of Italy and North America. One of the ensemble’s first stops was the Istrian town of Fiume. The Treaty of Versailles had made Fiume a supranational city-state, but the poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio had occupied it with an irregular army, claiming it for Italy as part of its war spoils. Even the horrors of the war had not dimmed Toscanini’s nationalism, and he was pleased by D’Annunzio’s troops’ display of military exercises. But the Italian army eventually dislodged D’Annunzio and his men: Fiume is now called Rijeka and is part of Croatia.

During the same period, Mussolini and his adherents had veered sharply to the right and adopted violent means to achieve power. On the eve of the Fascists’ March on Rome, in October 1922, which ended with King Victor Emanuel III calling on Mussolini to form a government, Toscanini told friends that if he were capable of killing a man, he would kill Mussolini.

In 1924 the mayor of Milan warned Mussolini that Toscanini would leave La Scala if the Fascist party insisted on dominating the theater’s board of directors; Mussolini acquiesced, for the time being. By 1926 Toscanini was making annual visits to the United States to conduct concerts with the New York Philharmonic, and in 1929 he left La Scala to become the Philharmonic’s principal conductor. The following year, he led the orchestra on its first European tour, which was wildly successful. While it was in Berlin, an Italian police informant said that Toscanini had declared himself “an anti-Fascist, because he held Mussolini to be a tyrant and oppressor of Italy, and…rather than break with these convictions he was prepared never to return again to Italy.” Mussolini read and underlined this statement in the report—one of the earliest significant documents in what would grow into a massive police file on Toscanini.

Before a concert in Bologna in May 1931, the 64-year-old conductor was slapped and knocked to the ground by a group of young Fascists for refusing to conduct “Giovinezza,” their party’s anthem. Reports of the incident appeared in newspapers around the world, and there were outcries of support for Toscanini’s stand. But in Italy, the muzzled press blamed his stubbornness for what had happened. Toscanini was too proud to reply in public, but privately he wrote: “The conduct of my life has been, is, and always will be the echo and reflection of my conscience, which does not know dissimulation or deviations of any type—reinforced, I admit, by a proud and scornful character, but clear as crystal and just as cutting.” He made up his mind not to conduct again in his native country as long as the Fascist regime, and the monarchy that protected it, continued to exist.

Toscanini had become the first non-German-school conductor to perform at the Wagner festival in Bayreuth, but on April 1, 1933, barely two months after the Nazis had come to power, he was the first signatory of a cablegram sent to Hitler to protest the boycott of Jewish musicians in Germany. At the request of the Wagner family, the new chancellor sent a letter to Toscanini, stating his hope to attend the maestro’s performances at Bayreuth that summer. But when Toscanini learned that conditions for Jews and other opponents of the new regime were worsening rather than improving, he withdrew from the festival.

It is almost impossible for people today, when the world of classical music has become so marginalized, to understand just how famous a cultural figure Toscanini was in his day, throughout Europe and in North and South America. Although he hated publicity and did everything possible to avoid it, his principled stand against the Fascist dictatorships was headline news on three continents. And instead of merely not conducting in Italy and Germany, he began to take his art to many other European countries.

At the end of 1936 Toscanini traveled to Palestine at his own expense and without a fee to conduct the inaugural concerts of an orchestra (now known as the Israel Philharmonic) made up mainly of Jewish refugees from Europe. His gesture prompted a letter from an amateur violinist named Albert Einstein, who wrote, “I feel the need to tell you for once how much I admire and honor you. You are not only the unmatchable interpreter of the world’s musical literature….In the fight against the Fascist criminals, too, you have shown yourself to be a man of the greatest dignity.”

In Austria, Toscanini had become an idolized guest of the Vienna Philharmonic, both in Vienna and at the Salzburg Festival, where his presence raised the festival’s profile—and its profits. But in February 1938, when Austrian chancellor Kurt Schusch-nigg made his first compromises with Hitler, Toscanini stated that he would not return to the festival. He responded positively to a request from the mayor of Lucerne, Switzerland, to conduct some performances there during the summer of 1938; the allure of Toscanini’s name persuaded other famous musicians who could not or would not return to Salzburg to join him in what became the first Lucerne Festival.

That same year Mussolini declared that Italians were “Aryans” and that Italian Jews were to be banned from public life—from owning or being partners in businesses that employed non-Jews, and from attending or teaching at Italian schools and universities. After Toscanini, whose mail was opened and whose telephone conversations were tapped, was heard describing Mussolini’s Manifesto of Race as “medieval stuff,” the Duce had his passport confiscated. Only when the international press began to learn about the incident did the image-conscious dictator have the document returned to its owner. Toscanini and most of his family then left immediately for the United States, where, the preceding year, after his retirement from the New York Philharmonic, he had become conductor of a new radio orchestra, the NBC Symphony, which had been created expressly for him. The 71-year-old maestro left his country—“with death in my heart,” he wrote to a friend—fearing that he would never again see Italy.

On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. Toscanini was beside himself with anger, saying he was ashamed of his country’s cowardly deed and its abandonment of England. During World War II, Toscanini remained in the United States. He supported the Mazzini Society, a group of liberal and socialist Italian expatriates who favored the establishment of an Italian republic following the anticipated end of Fascism. In September 1943, following Mussolini’s fall from power, Life magazine ran a guest editorial that was drafted by several of the society’s members and published under Toscanini’s name. The message protested the Allies’ policy of dealing with the Italian monarchy and with the government of Marshal Pietro Badoglio, who had supported the Fascist regime. Later that year Toscanini, who had turned down lucrative offers to appear in Hollywood films, participated, gratis, in Hymn of the Nations, a U.S. Office of War Information documentary about the role Italian-Americans played in aiding the Allies during World War II.

Throughout the war years Toscanini conducted numerous benefit concerts in New York to raise funds for the Red Cross and for War Bonds, among other causes, and he contributed money to all of them. At war’s end, he gave $10,000 toward the reconstruction of La Scala, which had been heavily damaged by Allied bombs in 1943, and in February 1946 he made up his mind to go home to conduct a concert for the rededication of La Scala.

As soon as he arrived in Milan, he began to lay down the law: Jewish and anti-Fascist musicians who had lost their positions at the house in 1938, and who had also managed to survive the German occupation of 1943–1945, were to be rehired. On May 11, 1946, La Scala, still smelling of fresh paint, was filled to nearly twice its normal capacity, and outside the theater tens of thousands gathered to listen to the performance on loudspeakers. At precisely 9 p.m., as the 79-year-old conductor walked onto La Scala’s stage for the first time in 16 years, people in the audience leapt to their feet, applauding frantically, shouting, and weeping. At the end of the last piece on the all-Italian program, the applause and cheering went on for 37 minutes, and afterward the members of the orchestra gave Toscanini a commemorative gold medallion that bore the inscription: “To the Maestro who was never absent.”

Toscanini conducted the fabled NBC Symphony Orchestra until his retirement in 1954. He died three years later in New York City. MHQ

HARVEY SACHS, a music historian, is the author of Toscanini: Musician of Conscience (Liveright, 2017) and the editor of The Letters of Arturo Toscanini (Knopf, 2002).

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Maestro of the Resistance

![]()